Social Identity and Cultural Scripts for a Good Death in Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cochran,-Diana---Seeing-Inside--The-Sea-Inside-.Pdf

“Among college-age youth (20–24 years) in the United States, suicide is the third leading cause of death.”1 Our youth today struggle with emotional and mental issues which are sometimes manifested in self-destructive behaviors or even attempts at suicide. Thus, I believe the Spanish film “Mar Adentro” (The Sea Inside) is powerful and relevant to our college-aged students. It relates the true story of Ramón Sampedro who is paralyzed in a diving accident and spends the next twenty-nine years of his life fighting for the legal right to carry out an assisted suicide. He loses the legal battle, but does find someone to help him end his life. He sips potassium cyanide from a straw as this person films his death. This event, which occurs in Galicia, Spain in 1998, sparks a national debate in Spain about the legality and justification of euthanasia, assisted suicide, and suicide in general. In the aftermath of Sampedro’s death, the filming of which was exposed to the public, his suicide assistant (a close female friend) is arrested, then released, and a popular campaign erupts in Spain with many claiming to be “the one” who helped him die. Even politicians show their support for his decision by signing a document stating they helped Sampedro to die.2 I use this film in a 300-level course called “Hispanic Culture through the Media Arts”. One of my objectives in the course is to begin to develop the skill of comprehending a wide variety of topics in films. This movie certainly helps in that regard. -

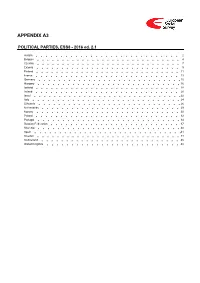

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Redalyc.Morte, Solução De Vida? Uma Leitura Bioética Do Filme Mar Adentro

Revista Bioética ISSN: 1943-8042 [email protected] Conselho Federal de Medicina Brasil Pessini, Léo Morte, solução de vida? Uma leitura bioética do filme Mar Adentro Revista Bioética, vol. 16, núm. 1, -, 2008, pp. 51-60 Conselho Federal de Medicina Brasília, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=361533250005 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto Morte, solução de vida? Uma leitura bioética do filme Mar Adentro Léo Pessini Resumo: Este artigo analisa o tema da morte assistida a partir de questionamentos levantados na película espanhola Mar Adentro (2004), do cineasta Alejandro Almenabar, sobre o drama do jovem marinheiro espanhol Ramon Sampedro. Além de comover platéias no mundo inteiro, o filme trouxe a público uma série de questionamentos éticos sobre a vida e a morte, dentre as quais destacam-se: qual o valor da vida humana quando marcada por deficiências que tolhem a liberdade e a autonomia? O que fazer quando não se encontra mais motivos para viver? Continuar a viver tentando ressignificar a vida seria possível ou a opção pelo suicídio assistido seria desejável como o fez Ramon Sampedro? Longe de assumir uma postura de juízes, mesmo discordando da solução final, este artigo argumenta pelo direito ao respeito ao qual todo ser humano faz jus. Palavras-chave: Morte. Eutanásia. Distanásia. Respeito. Autonomia. Liberdade. No início de 2005, dois filmes fizeram grande sucesso de crítica e público: Menina de Ouro, produção estadu- nidense, e Mar Adentro, filme espanhol, produzido por Alejandro Amenábar. -

Morte, Solução De Vida? Uma Leitura Bioética Do Filme Mar Adentro

Morte, solução de vida? Uma leitura bioética do filme Mar Adentro Léo Pessini Resumo: Este artigo analisa o tema da morte assistida a partir de questionamentos levantados na película espanhola Mar Adentro (2004), do cineasta Alejandro Almenabar, sobre o drama do jovem marinheiro espanhol Ramon Sampedro. Além de comover platéias no mundo inteiro, o filme trouxe a público uma série de questionamentos éticos sobre a vida e a morte, dentre as quais destacam-se: qual o valor da vida humana quando marcada por deficiências que tolhem a liberdade e a autonomia? O que fazer quando não se encontra mais motivos para viver? Continuar a viver tentando ressignificar a vida seria possível ou a opção pelo suicídio assistido seria desejável como o fez Ramon Sampedro? Longe de assumir uma postura de juízes, mesmo discordando da solução final, este artigo argumenta pelo direito ao respeito ao qual todo ser humano faz jus. Palavras-chave: Morte. Eutanásia. Distanásia. Respeito. Autonomia. Liberdade. No início de 2005, dois filmes fizeram grande sucesso de crítica e público: Menina de Ouro, produção estadu- nidense, e Mar Adentro, filme espanhol, produzido por Alejandro Amenábar. O último traz às telas a história verídica de Ramón Sampedro. Os dois filmes versam sobre o mesmo tema: a questão da eutanásia, do mor- Léo Pessini rer sem sofrimentos por opção. Professor doutor de teologia moral no mestrado stricto sensu em Bioética do Centro Enquanto esses filmes concorriam a prêmios, desenro- Universitário São Camilo (SP) lavam-se na vida real, com ampla cobertura da mídia, dois casos que acabaram sendo acompanhados em todo o mundo. -

Gimbernat. Revista Catalana D'història De La Medicina I De La Ciència. Volum LXIII

GIMBERNAT RevistaCatalana d'Història de la Medicina i dela Ciència Volum LXIIILVI Any 20115 (**)) ISSN: 0213-0718 Reial Acadèmia de Medicina de Catalunya Seminari Pere Mata. Universitat de Barcelona 5663 GIMBERNAT REVISTA CATALANA D’HISTÒRIA DE LA MEDICINA I DE LA CIÈNCIA Versió digital: www.ramc.cat Versió completa: www.raco/index.php/gimbernat E-mail: [email protected] Seminari Pere Mata. Universitat de Barcelona. Societat Catalana d’Història de la Medicina. Acadèmia de Ciències Mèdiques i de la Salut de Catalunya i de Balears. Seminari d’Història de la Medicina de la Reial Acadèmia de Medicina de Catalunya. Unitat d’Història de la Medicina de la Universitat de Barcelona. Unitat d’Història de la Medicina de la Universitat Rovira i Virgili. Unitat de Medicina Legal i Toxicologia de la Universitat de Lleida. Arxiu Històric de les Ciències de la Salut del Bages, COMB. Unitat d’Història de l’Odontologia de la Facultat d’Odontologia. Universitat de Barcelona. CONSELL DE DIRECCIÓ Jacint Corbella i Corbella (Reial Acadèmia de Medicina de Catalunya). Director. Lluís Guerrero i Sala (Arxiu Històric de les Ciències de la Salut). Director adjunt. Josep M. Calbet i Camarasa (Reial Acadèmia de Medicina de Catalunya) Manuel Camps i Surroca (Facultat de Medicina. Universitat de Lleida) Anna M. Carmona i Cornet (Facultat de Farmàcia. Universitat de Barcelona) Josep M. Ustrell i Torrent (Facultat d’Odontologia. Universitat de Barcelona) Carles Hervàs i Puyal (Societat Catalana de la Medicina. Acadèmia de Ciències Mèdiques) Ferran Sabaté i Casellas (Facultat de Medicina. Universitat de Barcelona) CONSELL EDITORIAL Josep Tomàs i Cabot. Edelmira Domènech i Llaberia. -

Denying Assisted Dying Where Death Is Not 'Reasonably Foreseeable'

Document généré le 25 sept. 2021 14:29 Canadian Journal of Bioethics Revue canadienne de bioéthique Denying Assisted Dying Where Death is Not ‘Reasonably Foreseeable’: Intolerable Overgeneralization in Canadian End-of-Life Law Kevin Reel Pourtours et défis d'une éthique en réadaptation Résumé de l'article Limits and Challenges of an Ethics in Rehabilitation La récente modification de la loi canadienne permettant l’accès à l’aide Volume 1, numéro 3, 2018 médicale à mourir en restreint l’admissibilité, entre autres critères, à ceux pour qui « la mort naturelle est devenue raisonnablement prévisible ». Une URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1058253ar révision récente de certains aspects de la loi a examiné les preuves concernant DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1058253ar l’accès à l’aide médicale à mourir dans trois situations de refus : demandes de mineurs matures, demandes anticipées et demandes pour lesquelles la maladie mentale est la seule condition médicale sous-jacente [1]. L’exigence de cet Aller au sommaire du numéro examen a été incluse dans la loi qui a introduit l’aide médicale à mourir au Canada. Tant le changement initial de la loi que l’examen lui-même négligent la prise en compte de ceux qui ont des souffrances intolérables, et pour Éditeur(s) lesquels la mort naturelle n’est pas raisonnablement prévisible. Cet article explore la possibilité d’étendre l’accès à l’aide médicale à mourir en Programmes de bioéthique, École de santé publique de l'Université de supprimant ce critère limitatif. Il considère également les défis éthiques que Montréal cela peut présenter pour ceux qui travaillent en réhabilitation. -

Anglo-American University School of International Relations and Diplomacy Spanish Populist Parties: an Alternative Understandin

Anglo-American University School of International Relations and Diplomacy Spanish populist parties: An alternative understanding of populism success. Master’s Thesis May 2019 Ana Caballero Díaz Anglo-American University School of International Relations and Diplomacy Spanish populist parties: An alternative understanding of populism success. by Ana Caballero Díaz Faculty Advisor: Professor Pelin Ayan-Musil A Thesis to be submitted to Anglo-American University in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Master in International Relations and Diplomacy (TT) May 2019 Ana Caballero Díaz Declaration of Consent and Statement of Originality I declare that this thesis is my independent work. All sources and literature are properly cited and include in the bibliography. I hereby declare that no portion of text in this thesis has been submitted in support of another degree, or qualification thereof, for any other university or institute of learning. I also hereby acknowledge that my thesis will be made publicly available pursuant to Section 47b of Act. No. 552/2005 Coll. and AAU’s internal regulations. i ABSTRACT Spanish populist parties: An alternative understanding of populism success. By Ana Caballero Díaz This thesis is based upon an original expert survey that divides the study of populism into two periods in Spain: from 2004 to 2011 and from 2011 to 2018, depicting a pre-crisis and a post-crisis context since Spain experienced a massive economic crisis and the 15-M protest movement in 2011. The survey compared the position of Spanish political parties in the left-right and the populist-nonpopulist spectrum in these two periods. -

MC COVID-19 Governmental Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Long-Term Care Residences for Older People: Preparedness, Responses and Challenges for the Future

MC COVID-19 Governmental response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Long-Term Care residences for older people: preparedness, responses and challenges for the future Spain Eloísa del Pino, Francisco Javier Moreno Fuentes, Gibrán Cruz-Martínez, Jorge Hernández-Moreno, Luis Moreno, Manuel Pereira-Puga, Roberta Perna Institute of Public Goods and Policies (IPP-CSIC) MC COVID-19 WORKING PAPER 13/2021 Contents 1. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS OF THE ROLE OF THE RESIDENTIAL CARE SECTOR FOR THE OLDER-AGE POPULATION (PRE-COVID19) 3 1.1. Trajectory of LTC until the most recent model 3 1.2. Current arrangements in LTC 4 1.3. Debates around the development of a LTC system 5 1.4. LTC governance 6 1.5. General functioning of the residential care system 8 2. DESCRIPTION OF THE EVOLUTION OF THE PANDEMIC IN SOCIETY AT LARGE, AND IN THE RESIDENTIAL CARE AND HEALTHCARE SECTORS MORE SPECIFICALLY 10 2.1. Evolution of the epidemic 10 2.2. The effects of the epidemic on the healthcare system 14 2.3. The epidemic in the public and political debates 18 3. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS OF THE MEASURES ADOPTED TO ADDRESS THE IMPACT OF THE PANDEMIC ON THE RESIDENTIAL CARE SECTOR FOR THE OLDER-AGE POPULATION 21 3.1. Background of preparedness for the Crisis 21 3.2. General Impact of the Epidemic on the Residential Care Sector and Policy Responses 25 3.3. Ensuring quality healthcare in nursing homes 34 3.4. The recovery of activity and the future of the residential sector 41 REFERENCES 43 MC-COVID19 text of institutionalized older-age care (age Project Coordinators: Coordination mechanisms in Corona- group that appears particularly vulnerable Eloisa del Pino Matute virus management between different in this epidemic context), in Spain as well Francisco Javier Moreno-Fuentes levels of government and public policy as in the rest of the EU-15. -

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Social Identity and Cultural Scripts for a Good Death in Spain

Advances in Applied Sociology 2013. Vol.3, No.2, 124-130 Published Online June 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/aasoci) DOI:10.4236/aasoci.2013.32016 Dying with Meaning: Social Identity and Cultural Scripts for a Good Death in Spain Fernando Aguiar, José A. Cerrillo, Rafael Serrano-del-Rosal Institute for Advanced Social Studies (IESA-CSIC), Cordoba, Spain Email: [email protected] Received February 8th, 2013; revised March 12th, 2013; accepted March 20th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Fernando Aguiar et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In this article we examine, through six focus groups, the various arguments put forth by social actors to defend or reject the right to choose how to die, including palliative sedation, euthanasia and even assisted suicide. This qualitative technique allows us to establish the relative weight of traditional, modern and neo-modern models of coping with death in the discourses of the Spanish subjects sampled within the study, how these models are reflected in specific cultural scripts and to what extent these scripts for a good death are the product of a reflexive project of identity. Keywords: Assisted Suicide; Cultural Scripts; Euthanasia; Reflexive Identity; Spain Introduction and ethical standards, on the other (IOM, 1997; DeSpelder & Strickland, 2005). As we shall see, however, this does not mean Spain is one of the countries of the European Union (EU) that this conception is uniform across the Spanish population or that has experienced the greatest and most rapid social, political does not coexist with other more traditional conceptions typical and economic changes in the last three decades (Pérez-Yruela of the previous decades. -

European Integration Cleavage in the 8Th and 9Th European Parliament - Master of International Public Management and Policy

European Integration Cleavage in the 8th and 9th European Parliament - Master of International Public Management and Policy Thijs Stegeman 430781 July 10th, 2020 Erasmus University Rotterdam Dr. Asya Zhelyazkova Prof. Dr. Markus Haverland 19274 words Summary As a result of the financial crisis of ‘08- ‘09 and the Euro crisis of ’13-’15, Euroscepticism has become more mainstream and gotten a more prominent place in political debates and elections. This development was particularly visible at the European Parliament (EP) elections of 2014, where anti-European parties significantly increased their share of parliamentary seats. According to Hix, Noury and Roland, this shift has caused a surge in the importance of the pro/anti-European integration division compared to the traditional left-right division, measured in voting behaviour. The 2019 EP elections were not preceded by a similar crisis, but still resulted in an increased share of seats for anti-European Members of the European Parliament (MEPs). Therefore, this thesis will focus on the composition of political cleavages in the complete eighth and the newly elected ninth term of the EP. The term political cleavage was first introduced by Lipset and Rokkan to describe divisions in society which were mirrored in politics. These divisions were usually competing world views which encompassed a varying range of issues, i.e. liberal market views opposed to government intervention. Traditionally, the left-right cleavage has been the most important, while in the 70’s and 90’s cultural values of universal values opposed to local, cultural values gained in importance. Some authors argue that the cleavage of European integration falls along the same division as the cultural cleavage, while others treat it as a new emerging cleavage, quickly gaining in importance. -

Revisiting Euthanasia

ZENTRUM FÜR EUROPÄISCHE RECHTSPOLITIK an der Universität Bremen ZERP Nuno Ferreira Revisiting Euthanasia: A Comparative Analysis of a Right to Die in Dignity ZERP-Diskussionspapier 4/2005 Nuno Ferreira is a doctoral student at the University of Bremen and a member of the Research Training Network “Fundamental Rights and Private Law in the European Union”, co-coordinated by the Zentrum für Europäische Rechtspolitik an der Univer- sität Bremen. IMPRESSUM Herausgeber: Zentrum für Europäische Redaktion: Rechtspolitik an der Vertrieb: Universität Bremen Universitätsallee, GW 1 28359 Bremen Schutzgebühr: € 8,- (zzgl. Versandkosten) Nachdruck: Nur mit Genehmigung des Herausgebers ISSN: 0947 — 5729 Bremen, im November 2005 Acknowledgements This text is partially based on a previous paper presented at the course “Bio- ethics and Medical Law in the New Millennium – the Future of Bioethics and Medical Law from a European and International Perspective”, which took place in August 2000 at the Law Faculty of the Helsinki University, Finland. I would like to thank Professor Doutor Guilherme de Oliveira, from the Faculty of Law of the University of Coimbra, for having offered me the possibility to participate in this course. I would also like to express my gratitude to Professor Dr. Josef Falke, Patrick O’Callaghan and Dr. Aurelia Colombi Ciacchi, from the Zentrum für Europäische Rechtspolitik an der Universität Bremen, and Dra. Patrícia Silva, from the Faculty of Law of the University of Coimbra, for their priceless contribution: this work would not have been possible without their help, advices and suggestions. Finally, I would like to thank my parents for having always supported so enthusiastically, both emotionally and finan- cially, my professional and academic career.