NACCL-20 Proceedings Volume 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armed Communities and Military Resources in Late Medieval China (880-936) Maddalena Barenghi Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia

e-ISSN 2385-3042 Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie orientale Vol. 57 – Giugno 2021 North of Dai: Armed Communities and Military Resources in Late Medieval China (880-936) Maddalena Barenghi Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Italia Abstract This article discusses various aspects of the formation of the Shatuo as a complex constitutional process from armed mercenary community to state found- ers in the waning years of Tang rule and the early tenth century period (880-936). The work focuses on the territorial, economic, and military aspects of the process, such as the strategies to secure control over resources and the constitution of elite privileges through symbolic kinship ties. Even as the region north of the Yanmen Pass (Daibei) remained an important pool of recruits for the Shatuo well into the tenth century, the Shatuo leaders struggled to secure control of their core manpower, progressively moving away from their military base of support, or losing it to their competitors. Keywords Shatuo. Tang-Song transition. Frontier clients. Daibei. Khitan-led Liao. Summary 1 Introduction. – 2 Geography of the Borderland and Migrant Forces. – 3 Feeding the Troops: Authority and the Control of Military Resources. – 4 Li Keyong’s Client Army: Daibei in the Aftermath of the Datong Military Insurrection (883-936). – 5 Concluding Remarks. Peer review Submitted 2021-01-14 Edizioni Accepted 2021-04-22 Ca’Foscari Published 2021-06-30 Open access © 2021 | cb Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License Citation Barenghi, M. (2021). “North of Dai: Armed Communities and Mili- tary Resources in Late Medieval China (880-936)”. Annali di Ca’ Foscari. -

Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-936) and Later Jin (936-947) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh- Century Sources

Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-936) and Later Jin (936-947) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh- century Sources Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München vorgelegt von Maddalena Barenghi Aus Mailand 2014 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans van Ess Zweitgutachter: Prof. Tiziana Lippiello Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 31.03.2014 ABSTRACT Historiography and Narratives of the Later Tang (923-36) and Later Jin (936-47) Dynasties in Tenth- to Eleventh-century Sources Maddalena Barenghi This thesis deals with historical narratives of two of the Northern regimes of the tenth-century Five Dynasties period. By focusing on the history writing project commissioned by the Later Tang (923-936) court, it first aims at questioning how early-tenth-century contemporaries narrated some of the major events as they unfolded after the fall of the Tang (618-907). Second, it shows how both late- tenth-century historiographical agencies and eleventh-century historians perceived and enhanced these historical narratives. Through an analysis of selected cases the thesis attempts to show how, using the same source material, later historians enhanced early-tenth-century narratives in order to tell different stories. The five cases examined offer fertile ground for inquiry into how the different sources dealt with narratives on the rise and fall of the Shatuo Later Tang and Later Jin (936- 947). It will be argued that divergent narrative details are employed both to depict in different ways the characters involved and to establish hierarchies among the historical agents. Table of Contents List of Rulers ............................................................................................................ ii Aknowledgements .................................................................................................. -

Singapore Chinese Orchestra Instrumentation Chart

Singapore Chinese Orchestra Instrumentation Chart 王⾠威 编辑 Version 1 Compiled by WANG Chenwei 2021-04-29 26-Musician Orchestra for SCO Composer Workshop 2022 [email protected] Recommendedabbreviations ofinstrumentnamesareshown DadiinF DadiinG DadiinA QudiinBb QudiinC QudiinD QudiinEb QudiinE BangdiinF BangdiinG BangdiinA XiaodiinBb XiaodiinC XiaodiinD insquarebrackets ˙ ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ ˙ 2Di ‹ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ #˙ [Di] ° & ˙ (Transverseflute) & ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ¢ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ b˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ s˙ounds 8va -DiplayerscandoubleontheXiaoinForG(samerangeasDadiinForG) -ThischartnotatesmiddleCasC4,oneoctavehigherasC5etc. #w -WhileearlycompositionsmightdesignateeachplayerasBangdi,QudiorDadi, -8va=octavehigher,8vb=octavelower,15ma=2octaveshigher 1Gaoyin-Sheng composersareactuallyfreetochangeDiduringthepiece. -PleaseusethetrebleclefforZhonghupartscores [GYSh] ° -Composerscouldwriteonestaffperplayer,e.g.Di1,Di2andspecifywhentousewhichtypeofDi; -Pleaseusethe8vbtrebleclefforZhongyin-Sheng, (Sopranomouthorgan) & ifthekeyofDiislefttotheplayers'discretion,specifyatleastwhetherthepitchshould Zhongyin-GuanandZhongruanpartscores w soundasnotatedor8va. w -Composerscanrequestforamembranelesssound(withoutdimo). 1Zhongyin-Sheng -WhiletheDadiandQudicanplayanother3semitonesabovethestatedrange, [ZYSh] theycanonlybeplayedforcefullyandthetimbreispoor. -ForeachkeyofDi,thesemitoneabovethelowestpitch(e.g.Eb4ontheDadiinG)sounds (Altomouthorgan) & w verymuffledduetothehalf-holefingeringandisunsuitableforloudplaying. 低⼋度发⾳ ‹ -Allinstrumentsdonotusetransposednotationotherthantranspositionsattheoctave. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscr^ Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscr^ has been reproduced from the microfiliii master. UMI films the text directty from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dqiendent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photogrsqths, print bleedthrough, substandard m argins, and inqnoper alignment can adversety affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note win indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with sm all overkq)s. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations aiq>earing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Nmnber OSOTTTS Situation types and aspectual classes of verbs in Mandarin Chinese He, Baoshang, Ph D. Th« Ohio State UaWanity, 1902 UMI 300 N. -

Ka-Wai Yeung

Taiwan Journal of Linguistics Vol. 4.1, 1-48, 2006 ON THE STATUS OF THE COMPLEMENTIZER WAA6 IN CANTONESE* Ka-Wai Yeung ABSTRACT Complementizers are generally known as function words that introduce a clausal complement, like that in English, for instance (Radford 1997). In many languages, complementizers are re-analyzed from verba dicendi, or verbs of ‘saying’ (Lord 1976; Frajzyngier 1991; Hopper and Traugott 1993; Lord 1993). This paper argues for the existence of a complementizer re-analyzed from a verb of ‘saying’ in Cantonese by providing a synchronic analysis of waa61. Waa6 has often been assumed to be a lexical verb in serial verb construction because of its following a ‘saying’ predicate or a cognitive predicate. However, this paper argues that waa6 is not always a verb, postulating that waa6 may have different meanings and subcategorizations in different situations, including waa61 meaning ‘say’ [__ (PP) CP] or [__ PP NP], the transitive verb waa62 meaning ‘blame/ * I am most grateful to Elaine Francis and Stephen Matthews for their constructive comments on the early drafts of this article. Thanks are also due to Sze-Wing Tang for providing some of the Cantonese examples and to Hilary Chappell for providing the Taiwanese Southern Min data in her article prior to publication. I am indebted to two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. 1 As is common practice for Mandarin and Taiwanese romanization, the paper use the Scheme for the Chinese Phonetic Alphbat (Hanyu Pinyin Fang’an) and Church Romanization, which was devised by Presbyterian missionaries in the 19th century in Taiwan. -

Listening to Chinese Music

Listening to Chinese Music 1 Listening to Chinese Music This article is an English translation of part of the book Listening to Chinese Music 《中國音樂導賞》edited by Chuen-Fung Wong (黃泉鋒) and published by the Hong Kong Commercial Press in 2009 as a project of the Chinese Music Archive of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. With the permission by the Chinese Music Archive, this article is uploaded onto the Education Bureau’s website for teachers’ and students’ reference. As for the recordings of selected music, please refer to the CDs accompanying the printed copy of the Chinese version. © The Chinese Music Archive, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced in any form or by any means. 2 Contents Foreword…………………………………………………………………………………..5 Translator’s Preface……………………………………………………………………….6 Chapter 1 Modern Chinese Orchestra ............................................................................. 8 Section 1 The Rise of the Modern Chinese Orchestra ......................................................... 9 Section 2 Instruments Used in the Modern Chinese Orchestra .......................................... 10 Section 3 The Characteristics of Chinese Orchestral Music and Its Genres ....................... 11 Section 4 The “Improvement” of Chinese Instruments ...................................................... 13 Section 5 The Development of Modern Chinese Orchestra ............................................... 15 Listening Guide ................................................................................................................... -

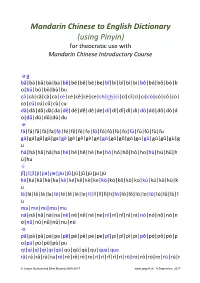

Using Pinyin) for Theocratic Use with Mandarin Chinese Introductory Course

Mandarin Chinese to English Dictionary (using Pinyin) for theocratic use with Mandarin Chinese Introductory Course ·a·a bā|bá|bǎ|bà|ba|bē|bé|bě|bè|be|bī|bí|bǐ|bì|bi|bō|bó|bǒ|bò|b o|bū|bú|bǔ|bù|bu cā|cá|cǎ|cà|ca|cē|cé|cě|cè|ce|ch|ch|cī|cí|cǐ|cì|ci|cō|có|cǒ|cò| co|cū|cú|cǔ|cù|cu dā|dá|dǎ|dà|da|dē|dé|dě|dè|de|dī|dí|dǐ|dì|di|dō|dó|dǒ|dò|d o|dū|dú|dǔ|dù|du ·e· fā|fá|fǎ|fà|fa|fē|fé|fě|fè|fe|fō|fó|fǒ|fò|fo|fū|fú|fǔ|fù|fu gā|gá|gǎ|gà|ga|gē|gé|gě|gè|ge|gō|gó|gǒ|gò|go|gū|gú|gǔ|gù|g u hā|há|hǎ|hà|ha|hē|hé|hě|hè|he|hō|hó|hǒ|hò|ho|hū|hú|hǔ|h ù|hu ·i· jī|jí|jǐ|jì|jia|jie|jiu|jū|jú|jǔ|jù|ju|jü kā|ká|kǎ|kà|ka|kē|ké|kě|kè|ke|kō|kó|kǒ|kò|ko|kū|kú|kǔ|kù|k u lā|lá|lǎ|là|la|lē|lé|lě|lè|le|lī|lí|lǐ|lì|li|lō|ló|lǒ|lò|lo|lū|lú|lǔ|lù|l ü ma|me|mi|mo|mu nā|ná|nǎ|nà|na|nē|né|ně|nè|ne|nī|ní|nǐ|nì|ni|nō|nó|nǒ|nò|n o|nū|nú|nǔ|nù|nu|nü ·o· pā|pá|pǎ|pà|pa|pē|pé|pě|pè|pe|pī|pí|pǐ|pì|pi|pō|pó|pǒ|pò|p o|pū|pú|pǔ|pù|pu qī|qí|qǐ|qì|qi|qū|qú|qǔ|qù|qu|qua|que rā|rá|rǎ|rà|ra|rē|ré|rě|rè|re|rī|rí|rǐ|rì|ri|rō|ró|rǒ|rò|ro|rū|rú|r © Jasper Burford and Ellen Burford 2005-2017 www.jaspell.uk 9 September, 2017 Mandarin Chinese to English Dictionary—using Pinyin ǔ|rù|ru sā|sá|sǎ|sà|sa|sē|sé|sě|sè|se|shā|shá|shǎ|shà|shē|shé|shě|shè |shī|shí|shǐ|shì|sho| |shū|shua|shui|shuo|sī|sí|sǐ|sì|si|sō|só|sǒ|sò|so|sū|sú|sǔ|sù|s u tā|tá|tǎ|tà|ta|tē|té|tě|tè|te|tī|tí|tǐ|tì|ti|tō|tó|tǒ|tò|to|tū|tú|t ǔ|tù|tu wā|wá|wǎ|wà|wē|wé|wě|wè|wō|wó|wǒ|wò|wo|wū|wú|wǔ|w ù|wu xī|xí|xǐ|xì|xiā|xiá|xiǎ|xià|xie|xio|xiu|xū|xú|xǔ|xù|xu|xü yā|yá|yǎ|yà|yē|yé|yě|yè|yī|yí|yǐ|yì|yō|yó|yǒ|yò|yū|yú|yǔ|yù|y ua|yue|yü zā|zá|zǎ|zà|zē|zé|zě|zè|ze|zhā|zhá|zhǎ|zhà|zhē|zhé|zhě|zhè|z hī|zhí|zhǐ|zhì|zhō| zhǒ|zhò|zhū|zhú|zhǔ|zhù|zhu|zī|zí|zǐ|zì|zi|zō|zó|zǒ|zò|zo|zū|z ú|zǔ|zù|zu|zua| zuǐ|zuì|zuō|zuó|zuǒ|zuò| 2 www.jaspell.uk 9 September, 2017 Mandarin Chinese to English Dictionary—using Pinyin Notes 1 The list of Pinyin words is arranged in Roman (English) alphabetical order for each letter, irrespective of groupings that respresent Chinese syllables or their order in Chinese Hanzi writing based on radical and character indices. -

NACCL-20 Proceedings Volume 1

Proceedings of The 20th North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL-20) Dedicated to Professor Edwin G. Pulleyblank in honor of his 85th birthday VOLUME 1 East Asian Studies Center Edited by 25-27 April 2008 Marjorie K.M.Chan Columbus, Ohio and Hana Kang Cover graphics designer: Graeme Henson Printing manager: Jennifer McCoy Bartko © Cover design and front matters by NACCL-20 2008 © All papers copyrighted by the authors 2008 Proceedings of the 20th North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL-20). Volume 1 / edited by Marjorie K.M. Chan and Hana Kang ; contributors, Edwin G. Pulleyblank … [et al.] p. cm. ISBN: 978-0-9824715-0-0 1. Chinese language—Congresses. For information on NACCL-20 (held on 25-27 April 2008, Columbus, Ohio), visit our website at http://chinalinks.osu.edu/naccl-20/ Published by: East Asian Studies Center The Ohio State University 314 Oxley Hall 1712 Neil Avenue Columbus, Ohio 43210 USA easc.osu.edu Printed and bound by UniPrint, 2500 Kenny Road, Columbus, Ohio, USA. CONTENTS OF VOLUME 1 Page Preface ….…….………....………….……..…...…..………………...……...…... ix Acknowledgements ….…….………....………….……..…...…..….....……...…... xi History of NACCL: The first two decades ……..……......….…..….....……...…... xiii Dedication to Professor Edwin G. Pulleyblank ……..……...……..…………..…... xix ICS Lecture introduced by Jennifer W. Jay and Derek Herforth PART 1. PLENARY AND INVITED PAPERS I PULLEYBLANK Edwin G (Plenary Speaker & ICS Lecture Series Speaker) …….. 1 Language as digital: A new theory of the origin and nature of human speech II TAI James H.-Y. (Plenary Speaker) ……………………………………………. 21 The nature of Chinese grammar: Perspectives from sign language III LI Yen-hui Audrey (Plenary Speaker) …………..……...……………………… 41 Case, 20 years later IV ERNST Thomas (Invited Speaker) …………..........……………….………….... -

The Later Tang Reign of Emperor Mingzong

From Warhorses to Ploughshares The Later Tang Reign of Emperor Mingzong Richard L. Davis Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2014 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8208-10-4 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments ix Preface xi Chart 1: Ancestry of Li Siyuan xvi Map 1: Map of Later Tang, ca. 926 xiv Chapter 1: People and Places 1 The conI 1 The Shatuo People 6 The Life and Legacy of Li Keyong 11 Imperial Women 15 Sons 18 Surrogate Sons 21 The upremeS Sibling Rivalry 24 Cast of Political Characters 26 Chapter 2: Royal Passage 33 The Slow Climb 33 The bortedA Reign of Zhuangzong 39 Unruly Guards and Bodyguards 42 The epidT Regent 49 Chapter 3: Political Events: The Tiancheng Reign, 926–930 63 Chapter 4: Political Events: The Changxing Reign, 930–933 89 Chapter 5: Institutions, Reforms, and Political Culture 121 Governing Officials 121 Law and Order 126 Campaign against Corruption 131 Historical Practices and Projects 134 Culture 137 Education and Examinations 140 From Finances to Technology 147 viii Contents Chapter 6: Volatile Periphery 155 The Shatuo-Kitan Rivalry 155 Nanping 162 Sichuan in Revolt 164 Epilogue 177 The bortedA Rule of Li Conghou (r. -

Ethnomusicology 126: Musical Practices of the World Fall and Winter Quarter 2012 – Tuesday and Thursday 11:00Am-1:00Pm, Friday Discussion Section

Ethnomusicology 126: Musical Practices of the World Fall and Winter Quarter 2012 – Tuesday and Thursday 11:00am-1:00pm, Friday Discussion Section Instructor: Brian Hogan University of California, Santa Cruz Department of Anthropology office: Social Sciences II 410 e-mail: [email protected] office hours: by appointment classroom: Social Sciences I 210 COURSE DESCRIPTION This upper division course in ethnomusicology provides an introduction to selected musical cultures of the world. Focusing on differences in musical practice, the goal of the course is to convey both the breadth and diversity of music from the world over, critically examining some of the numerous cultural frameworks through which music created, conceived, and valued. Through this anthropologically oriented survey, we come across many issues surrounding the interrelatedness of music with other cultural areas, including language, dance, visual art, religion and spirituality, style and identity, modernization and cultural change, and many other issues. We will examine music across several different historical periods throughout the quarter, drawing upon a variety of studies to develop anchor points of understanding on several continents while attending to both traditional and contemporary styles. The course consists of several units divided by geographic area, and organized according to the prominent or unique musical characteristics of a particular region or style. The format of the class is a series of modified lectures, which incorporate musical examples through audio, video, and in-class performances. No musical background is required for this class, aside from a keen interest and enthusiasm for music and musical activity. COURSE REQUIREMENTS Regular attendance in class and Friday sections is required, as well as the completion of all three written assignments, as well as the midterm and final exams. -

In the Zizhi Tongjian and Its Sources

Scuola Dottorale di Ateneo Graduate School Dottorato di ricerca in Lingue Culture e Società Ciclo XXVI Anno di discussione 2014 Historiography and Narrative Construction of the Five Dynasties Period (907-960) in the Zizhi tongjian and its Sources. Settore scientifico disciplinare di afferenza: L-OR/21, L-OR/23 Tesi di dottorato di Maddalena Barenghi, 955781 Coordinatore del Dottorato Tutori del Dottorando Prof. Federico Squarcini Prof. Tiziana Lippiello Prof. Hans van Ess Table of Contents Chronology .................................................................................................................. iv Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 Writing Historical Guides for Proper Government in the Eleventh Century........ 1 Chronological Framework of the Zizhi tongjian................................................. 11 Structure of the Annals…………………………………………………………………15 Lessons from a Period of Disunity……………………………………………………22 Recent Scholarship……………………………………………………………………..28 Abridgments……………………………………………………………………..32 Chapter One: The Zizhi tongjian and its Sources for the History of the Five Dynasties Period .......................................................................................................................... 39 1. Early Tenth-Century History Writing ................................................................ 40 1.1. The Liang Taizu shilu and the Da Liang bianyi lu ........................................ 41 1.2. -

Fire and Ice

Fire and Ice Li Cunxu and the Founding of the Later Tang Richard L. Davis Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2016 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8208-97-5 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Hang Tai Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface x Acknowledgments xiii Chapter 1 Th e Prodigal Son 1 Roots 3 Doting Father 7 Succession as Prince 13 Maternities 14 Inner Circle 22 Th e Lord of Nanping 30 Chapter 2 Vassals and Kings 32 Generational Rift s 32 Early Expansion 37 Reprisal against Yan 46 History Summons at Weizhou 56 Barbarians and Chinese 65 Southern Off ensive 71 Tensions Within 77 Alliances Matter 81 Final Transition to Dynasty 85 Lingering Volatility 88 Chapter 3 Th e Tang Renaissance 91 Launching the Tongguang Reign 91 Dominoes in the Heartland 96 Consolidating Power 107 Th e Sway of Favorites 113 Celebrations 120 Rapprochement with Neighbors 126 viii Contents Culture Wars 130 Tormented Adopted Brother 142 Extravagance and Histrionics 144 Chapter 4 Raging Tempest 148 Ties Th at Bind 148 Th e Middle Palace 154 Shu