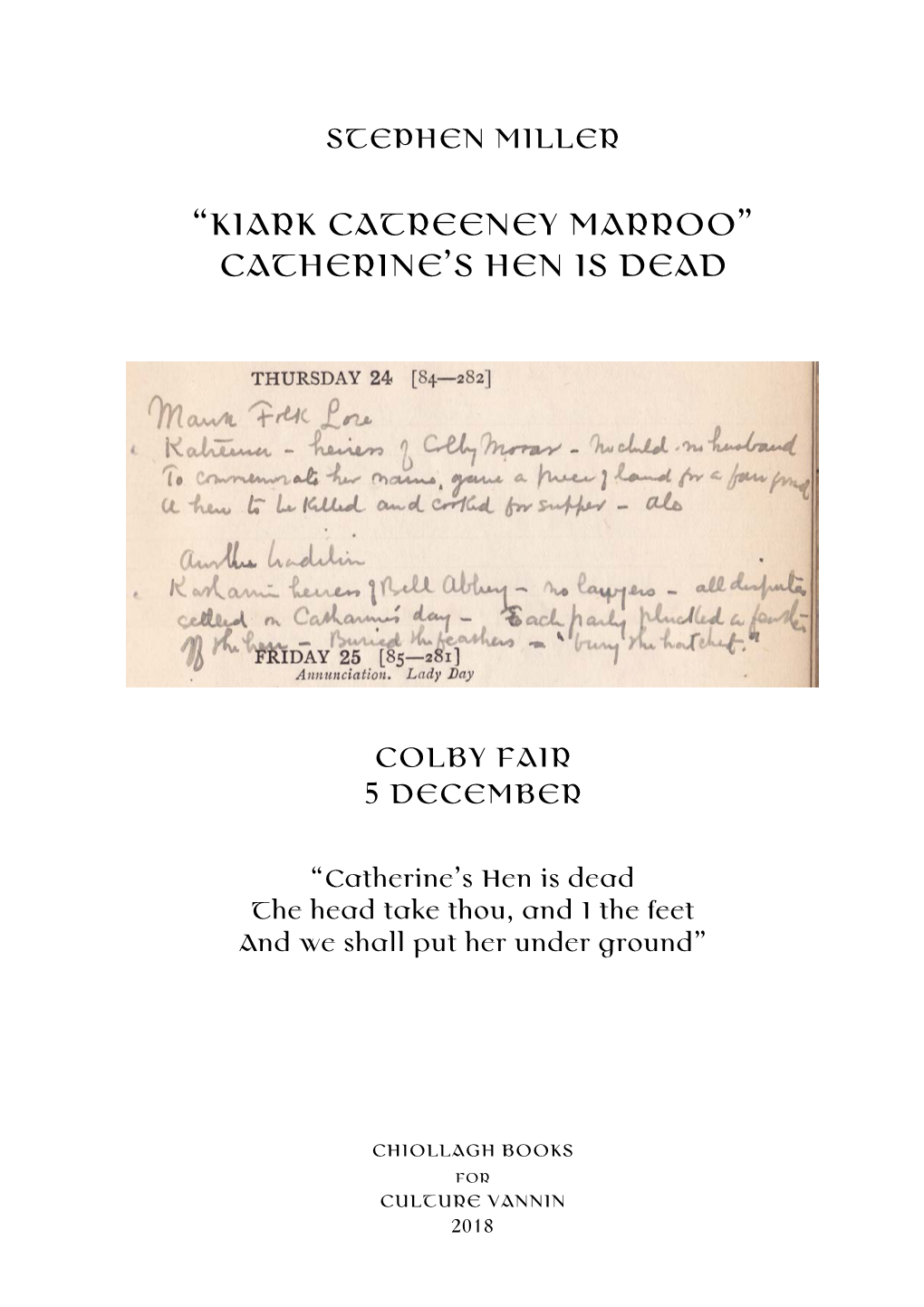

Kiark Catreeney Marroo” Catherine’S Hen Is Dead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Militia Officers' Reward of Merit Mr. Foster's Mission Successful John

/ VOL. XXI ALEXANDRIA, ONJARIO, FRIDAY, AUGUST 8, 1913 29 Teachers "Wanted TEACHER WANTED Militia Officers’ Mr. Foster’s ^Highland Blood Two Keels To Heavy Fines For A qualified teacher for S.S. No, 10, Kenyon. Duties to commence Sept. 1. Mail Contract Apply stating salary and quajifications Mission Successful In New Bishop Germany’s Bee Selling Unfit Fnnii to A. K. McDonald, Sec.-Treas.,Green- Reward of Merit SEALED TENDERS, addroiwod to field, Ont., box 17. 29-3 ^ (From the Montreal Gazette.) Hon. Geo. E. Foster, Minister of Rev. Father Joseph Guillaume London, August 6,—Germany In these days, when the high cost 'the Po«tana»ter G€0ieral, be reoeiv> 'J'rade and Commerce, who for the Forbes, parish priest of St. John Bap- bids aE>ove the present navy law, then of living is the householder^ chief ed at Ottawa until Noon, on Friday, Ottawa, August 3.—As a result of | paat five months has been in the tiste Church of Montreal, has been our policy will t>e two keels to one,” worry, the purchaser of an article of 12th, S^tember 1913, for tha oon* the plan inaugurated last year by the I food, naturally wishes to “get his ihe TEACHER WANTED Antipodes, mid the Orient, on a mis- appointed Bishop of Joliette in succes- was the striking state ent of Lord veyanoe o! Éit Uajeaty*a Hails, on a Minister of Militia and Defence of I sion of industrial expansion, is ex- sion to the late Bishop Archambault. A*hby St. Ledgers, durii^ the House money’s worth,” and that every time. -

Tynwal D Court

TYNWAL D COURT. DOUGLAS, THURSDAY, MAY 5, 1898. Present (in the Council): His Excellency the Lieut.-Governor (President of the Court), Deem ster Gill, the Attorney-General, the Receiver- General, and the Vicar-General ; (in the Keys) Messrs John Joughin (Acting-Speaker), A. W. Moore, T. Clague, T. Allen, .1. C. Crellin, D. Maitland, E. H. Christian, W. Quayle, J. R. Kerruish, J. A. Mylrea, J. T. Cowell, J. R. Cowell, James Mylchreest, W. Quine, J. Qualtrough, J. D. Clucas, E. T. Christian, J. J. Goldsmith, R. Cowley, R. Corlett, and F. G. Callow. Mr Story, Clerk to the Council, and Mr Gelling, Secretary to the Keys, were in attendance. PROCEDURE. 'The Governor : I propose that we should go on with the agenda as far as possible to-day, so as to lighten it when we next meet. The two important points are—first of all—the Bills Lw signature, in order to obtain the Royal assent, and the second important point is the resolution with regard to the Customs duties. I do not think either of those matters will take a long time, and afterwards we shall pi oceed as far as possible with the other business on the agenda. BILLS SIGNED. The following Bills were submitted for signa- ture ;—Merchandise Mc.rks; Bishop Barrow's Charity (Girls' High School); Port Erin and Port St. Mary Light ; Education ; St. Matthew's Church Bill. TITHE COMMUTATION BILL. The Governor : The Acting-Speaker has called my attention to some little inaccuracies in the wording of one of the Bills, and I have given directions that they shall be corrected according to the original Bill passed by both branches. -

Doing a Good Deed: the Uniqueness of the Manx Deed

May 2020 Doing a Good Deed: The Uniqueness of the Manx Deed. The Legal Mechanism of the Deed It was said by the English Kings Bench Division in Sharington v Strotton (1564) 1 Plow. 298, 308 that the law of England was that there were two ways of making contracts or agreements. One by words and one in writing. The court opined that because words “are oftentimes spoken by men unadvisedly and without deliberation”, a contract by words alone will not bind without valuable consideration (being a benefit gained or detriment suffered, per Lush J (at 162) in Currie v Misa (1874) LR 10 Ex 153). However, this would not be the case when an agreement was made by deed which would represent an enforceable promise made without valuable consideration due to the formality of the decision to make an accord. The court stated in Sharington v Strotton at [308]: - “For when a man passes a thing by deed, first there is the determination of the mind to do it, and upon that he causes it to be written, which is one part of deliberation, and afterwards he puts his seal to it, which is another part of deliberation, and lastly he delivers the writing as his deed, which is the consummation of his resolution; and by the delivery of the deed from him that makes it to him to whom it is made, he gives his assent to part with the thing contained in the deed to him to whom he delivers the deed, and this delivery is as a ceremony in law, signifying fully his good-will that the thing in the deed should pass from him to the other.” Contracts by deed therefore played a role in the common law to protect the party or parties from imprudent commitments. -

Petitions of Doleance, Status Quo and Actions of Arrest Are Useful Manx Remedies and Should Be Retained” - Discuss1

“Petitions of Doleance, Status Quo and Actions of Arrest are useful Manx remedies and should be retained” - discuss1 Three very Manx remedies Paul Rodgers, Articled Clerk2 1 George Johnson Law Prize Essay 2009; Essay (c) 2 Articled to Irini Newby; Articles commenced November 2007 Page 1 ~ -.- ~ Table of Contents ~ -.- ~ 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 PETITION OF DOLEANCE ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Usefulness in the Separation of Powers ........................................................................................................... 4 2.3 The lack of procedural bureaucracy ................................................................................................................. 5 2.4 Time Limits ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 2.5 Usefulness – Sufficiency of remit and power .................................................................................................. 8 2.6 Issues of cost ................................................................................................................................................... -

Jersey & Guernsey Law Review | a Very Particular Remedy: Doleance In

Jersey & Guernsey Law Review – June 2011 A VERY PARTICULAR REMEDY: DOLEANCE IN THE CROWN DEPENDENCIES Lucy Marsh-Smith This article examines the origin, scope and extent of the Doléance1 remedy in the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man, concluding that the remedy has developed on diverse lines, so that the common name gives rise to actions very different in scope when one compares the customary law with Manx common law. 1 In the Guernsey case of Bassington Ltd v HM Procureur,2 Collins, JA, President said— “The inhabitants of Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man have certain very particular remedies each of which is named a Doléance. Both the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man have in the past considered the remedy peculiar to themselves, without apparent knowledge of the existence of a remedy similarly named in the other jurisdiction. Thus the Deemster in Re the Attorney General of the Isle of Man3 considered it was unique to the Isle of Man, and there is one reference to it having been said that it is peculiar to the Channel Islands (see Bentwich—Practice of the Privy Council in Judicial Matters 3rd ed (1937), at p 54). The nature of the remedy and the means by which it is employed may differ. In the Isle of Man and Jersey it is already well established that the local Courts have jurisdiction to hear a Doléance. In Guernsey the position is much less clear.” Doleance in the Isle of Man 2 Before considering the position in the Channel Islands any further it is helpful to set out the main features of the doleance remedy in the Isle of Man, a jurisdiction where one would not expect to find the use of a French term. -

MBM Personalia

A.W. MOORE MANX BALLADS AND MUSIC (1896) WORKING GUIDE (8) PERSONALIA K CHIOLLAGH BOOKS 2017 Vers. 1.0 A.W. MOORE MANX BALLADS AND MUSIC (1896) 1 introduction Whilst A.W. Moore’s name appears on the title page to Manx Ballads and Music, the work involved in its compilation and editing was not his alone as he acknowledged within its pages. For starters, he did no collecting himself, drawing instead on the efforts of Henry Bridson in the main, along with Annie Gell, Elizabeth Jane Graves, and John Edward Kelly. The tunes that appeared in harmonised form were prepared by Mary Louisa Wood and Edith Lilian McKnight and overseen by Colin Brown. A number of individuals submitted tunes and texts seemingly from their own recollection, namely Robert Henry Bridson (referred to as Harry Bridson), Thomas Edward Brown, William Cashen, Margaret Frissel Ferrier, Robert Kerruish, Rev. John Kewley, and James Bell Nicholson. Texts were passed to Moore by John Rhys and Karl Roeder. William John Cain edited the Manx of the texts, T.E. Brown wrote the preface, and John Miller Nicholson provided the illustrations. And, finally, there are the singers themselves: John Bridson, John Cain, Philip Cain, John Christian Cannell?, Henry Cregeen, Thomas Crellin, James Gawne, Mary Ann Gawne, William Harrison, Thomas Kermode, John Lace, John Quayle, and Thomas Wynter. To round matters off, there was Margaret Kelly, the source of an anecdote about Thurot and Elliot, and a ‘Miss Teare’ who was the source of a children’s rhyme, and to end with the unnamed singer who sang Lhigey, Lhigey for E.J. -

Tynwald Cott Ht

TYNWALD COTT HT. DOUGLAS, TUESDAY, MAY 30, 1899. Present—In the Council : His Excellency the Lieut.-Governor (President), the Lord Bishop, Deemster Sir James Cell, the Receiver-General, and the Vicar-General; in the Keys: Mr A. W. Moore, J.P. (Speaker), Messrs D. Maitland, E. T. Christian, 'I'. Allen, J. C. Crellin, J. D. Clucas, W. Quine, W. Quayle, J. A. Mylrea, W. J. Kermode, J. J. Goldsmith, R. Cowley, T. Clague, J. R. Kerruish, Jos. Qualtrough, James Mylchreest, J. T. Cowell, and E. H. Christian. ACCIDENT TO THE CLERK OF THE ROLLS. The Governor: I am sure you will join with me in sympathising most sincerely with the Clerk of the Rolls for tho very bad accident which has happened to him. We regret it very much in- deed. I understand he is contlned to his house. I am sure we are all very sorry that he is not here to-clay, and I am quite certain we shall join in sympathising with him in his illness. FINANCIAL STATEMENT BY HIS EXCELLENCY. The Governor :I propose this morning to make to you as short and concise a statement as 1 can-- I shall make no preface to it—with regard to financial business. If you look at pages 20 and 21 of the statement, you will see he prospective balance on March 31st, 1900, shown there ie £4,500, including £1,700, interest on loans advanced to local bodies. Since the financial statement was issued, I have ascertained that the cost of the volunteers, estimated at £1,000, will not exceed, we will say, £500. -

TC-19000308-V0017

TYNWALD COU RT. DottOL.ks DiuitsuAr. INIAnClt 8, 1900. Present:—M. the Council—his Excellency the Lieutenant-Governor (I..ord Henniker), President of Ihe Court; Deernster Sir James Bell, Deemster Kneen, Lbe Attorney-General, the Receiver- General, the Vicar-General, and the Archdeacon. In the Keys—the Speaker, Messrs J. ,Toughin, T. Chigoe, .1. T. Cowell, W. Quine, R. Kaighen, W. Quayle, j. R. Kerruish, R. Corlett, D. :Maitland, T. Corlett, J. C. Crellin, T. Allen, ,T, Mylehreest, J. J. Goldsmith, Jt Cbleas, J. R. Cowell, W. J. Kermorle, ;old J. I). Clueas. QTJ ESTIONS. The. Governor: I think there were some gentle- men in 'he House wanted to ask me some ques- tions to-day. As am in a hurry to-day, I think the most convenient way would be to postpone iL to the next Court. Air Quine said he would give his Excellency notice of his question in writing. THE BEER DUTIES. The G-overnor: T ;1771 going to ask you to pass this resolution, and then, directly- afterwards, I am going to introduce a Bill to bring it into effect in a proper manner. The Bill ought to be passed at once. It is rt very short. one, and I shall a=lt the Council to go into iL at once. and I shall ask gentlemen of the House of Keys to wait here for a few moments, and probably we will settle the matter in a very short. time. The Attorney- General was good enough to draft the Bill; he has taken a great, deal of trouble with it. -

England and the Isle of Man

When Is a Colony Not a Colony? England and The Isle of Man Augur Pearce* Abstract Manx emancipation from English tutelage still falls short of independence. Island courts' and constitutionalists' efforts to reconcile the continuing role of Crown and Parliament with insular aspirations are typified by dicta of the Staff of Government Division in Crookall v Isle of Man HarbourBoard and Re CB Radio Distributors. These cases suggest the Queen legislates for the Island as Lord of Man, successor to its former rulers; whether with Parliament or with Tynwald is secondary, so an Act of either body can repeal inconsistent Acts of the other. This article contests the claim of continuity between former rulers and the Kings of England, also the assumption that there can be no hierarchy between different legislative acts of the one ruler. This article argues that the law considers Man conquered by English arms in 1399, a continuity breach which gave King and Parliament un- fettered law-making power as explained in Calvin's Case and Campbell v Hall. Centuries of government by royal tenants-in-chief do not affect the position after the surrender of their estate. Royal continuance of the former Lords' concessions to Tynwald, and Man's exclusion from the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865, are both explicable on policy rather than constitutional grounds. I. The Limits to Manx Emancipation The past 150 years have seen a steady emancipation of the Isle of Man from English tutelage. But there remain significant areas in which that emancipation falls short of independence. The United Kingdom Parliament remains (in succession to the Par- liament of England) the Island's supreme legislature. -

Petitions of Doleance2 and a Significant Body of Case Law

Judicial Review The Petition of Doleance The procedure on the Isle of Man for challenging or seeking judicial review of an administrative action is by way of a Petition of Doleance. “A petition of doleance is the process by which the High Court exercises its supervisory jurisdiction over the proceedings and decisions of inferior courts, tribunals and other bodies or persons who carry out quasi-judicial functions or who are charged with the performance of public acts and duties.” Per Deemster Kerruish QC1 The Island has well-established jurisprudence in respect of petitions of doleance2 and a significant body of case law. In Re Kerruish3 in 1971 Bingham, JA described the purpose of a Petition of Doleance as— “…to provide within a comparatively compact community a simple and speedy means for the ordinary citizen to obtain redress for injustices which in England would be remedied by orders of habeas corpus, certiorari and the like. The essence of the petition of doleance is that it should be simple and, therefore, unencumbered by legal formality and also speedy so that the cases can be tried quickly.” The often judicially quoted definition of the petition of doleance is to be found in the case of Corkish v Boyd 4 in 1904 where Sir James Gell CR said— “This petition is one of doleance, seeking the relief which in England is obtained by the prerogative writ of certiorari. There is no such writ here, neither have we any of the English prerogative writs such as habeas corpus, mandamus etc. Substantially, however, the relief obtainable by means of these writs is obtained here by a different mode of procedure, namely the petition of doleance, formerly heard in the Court of the Staff of Government Division but, since the passing of the Judicature Act 1883 in (the Chancery Division) of the High Court … The procedure here is entirely different from that in England. -

The Surnames & Place-Names of the Isle Of

6Xavv, S-h^. : c u^^^/^a^ y^/2^'^/)a.<^ THE x^y/ SURNAMES & PLACE-NAMES OF THE ISLE OF MAN. BY A. W. MOORE, M.A ®iitk m\ introburtiou BY PROFESSOR RHYS. '' As no impresses of the past a^e so abiding^ so none, when once attention has been awakened to ihetn, are so self-evident as those which najnes preserve.'—Trench (on ' The Study of Words.') LONDON ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1890. f^*^^''^'^,. >9S 30 U^f '-^ VIClK:!^ PREFACE. I AM at a loss what excuse to make for thrusting my- self into the foreground of this work, except that I have found it too hard to say ' nay ' to its author, whom I have known for years as a scholar who takes the keenest interest in all that relates to the history of his that he had singular facilities for studying everything of the nature of documentary evidence bearing on Manx proper names. Those who happen to have been acquainted with the 'Manx Note Book,' edited with such ability and such excellent taste by Mr. Moore, will agree with me in this reference to him. It always struck me as a pity that he should not place on record the fruits of his familiarity with the official records of the Island; and the expression, on my part, of that feeling on sundry occasions, is the only possible merit to which I could lay claim in connexion with this volume. The ground to be covered by the work is defined by the geography of Man, and so far so good ; but on the other hand, proper names, whether of persons or of ^itcface. -

A DEVONIAN LODGE TN LONDON. It Was to Be Expected That When

CONTENTS. forwarded to the Grand Master, with a request that PAGE he would be LEADERS- . A Devonian Lodge in London ... ... ¦•• ••• 5" pleased to summon a special meeting of Grand Lodge for the Mason ry in New South VVales ... ... ••• ••• 5" ^ purpose of taking into consideration Masonic Juri sprudence ... _ _ ... _ _ ••• . — ••• ••• S'2 the action of the President ... 2 Unite d Grand Lodge of England (Agenda Paper) ... ... 5* in ruling the member's motions out of order. Ma rk Grand Lodge (Agenda Paper ) ... ... ... ••• 5*3 The Grand Grand Lodge of Isle of Man ... ... ... - 5'.1 Prov incial •¦¦ Master declined to accede to the request of the petitioners ; An Addres s ... — <•• — — •• 5'5 M ASONIC NOTES— but as he considered the question whether the President' s Agenda Paper of United Grand Lodge of Eng land... ... ... 5'7 Agenda Paper of Mark Grand Lodge ... ... ... ¦•• 5'7 Reports of the Board's proceedings should be submitted to the Mason ic Jurisprudence ... ... ... ••• ••• 5'7 Board previous to being presented to Grand ••¦ Lodge was well Corres pondence ...of ... _ ••• — ... ••• 5'8 Provi ncial Gra nd Lod^e Devonshire ... ... ••• S^ worthy of being considered, he announced his intention of Ihe Bond of Brothe rhood ... ... ... ... ••• S20 Obitua ry ... ... •» - - - - 52 ' referring the subject to Grand Lodge at its next regular meeting Science, Art and the Drama ... ... ... ... ••¦ 522 Misonic and General Tidings ... ... ... ... ••¦ 524 in June. At the regular meeting of the Board of General Purposes Craft Masonry ... ... ... ••• — •¦• 524 in April , after the minutes of the previous Board had been con- firmed , a motion for adjournment was carried in sp ite of an appeal VONIAN LODGE TN LONDON.