The Surnames & Place-Names of the Isle Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 31, 2021

St Mary’s Parish, Drogheda Sunday 31st January 2021 Fourth Sunday In Ordinary Time Fr Phil Gaffney PP St Mary’s Parish Centre Fr Ciprian Solomon CC 24 James Street St Mary’s Presbytery 9834587 9838347 Dublin Road 9834958 www.stmarysdrogheda.ie Hospital Visitation: is not possible at the moment, however please continue to inform Fr Phil or Fr Ciprian if a relative is ill or in hospital. In this first chapter Mark familiarises his readers with the type of things Jesus did to proclaim the kingdom, the Reign of St Mary’s Schedule (On webcam only.) God. Our passage today touches on two of these, the first being that ‘he taught as one having authority’. It makes a We earnestly hope that in 2021 we will find ourselves vaccinated, going back to work or difference when you listen to someone who is clearly speaking from experience and personal knowledge. Remember finding new jobs, heading back to school, and breathing a sigh of relief. people who impressed you in this way. We all look forward to a resumption of our visits to our elderly in our nursing homes and Jesus’ combined teaching with healing, and he drove the evil spirit out of the man. The power of God that worked this those who have been confined to their homes. Our prayers are with those families who lost wonder through Jesus is also at work in and through us today. When have you been freed from some bad habit? loved ones during the course of the pandemic. Yet, like we do in the seasons of Advent and The evil spirit convulsed the man before it left him. -

• COLLEGE Mflfilzine »

THE • COLLEGE MflfilZINE » PUBLISHED THREE TIMES YEflRiy THE BARROVIAN. No. 203 FEBRUARY 1948 CONTENTS Page Page Editorial 397 Holland 419 Random Notes 398 Impressions of Spain and Masters 399 the Basque Country ... 420 School Officers 400 Germany and the Germans 423 Salvete 400 Jamboree 424 Valete 401 General Knowledge Paper 42.5 Founders' Day 401 The Societies 431 Honours List 403 Aero Modellers' Club ... 436 Prize List 404 Cambridge Letters 436 O. K. W. News 406 House Notes 437 Obituary 407 J.T.C. Notes 441 Roll of Service 409 Scouting 442 King William's College Swimming 443 Society 409 Shooting 443 King William's College Rugby Football 443 Lodge 410 The " Knowles " Cup ... 444 The Concert 410 Chapel Window Fund ... 452 St. Joan 412 K.W.C. War Memorial Mr. Broadhead 415 Fund 453 Chapel Notes 415 O.K.W. Sevens Fund ... 457 The Library 417 Contemporaries 457 France 418 EDITORIAL. The School Magazine can do its work by two methods. The firsc is the chronicling of the bare facts of school life, the lists of the terms functions and functionaries, and the Sports events. The second is the interpretation of the spirit of the school and of its multifarious activities by means of descriptive writing. Often the two methods are mixed; for instance, the report on the play will contain both the programme and a criticism of the production or, an account of a Rugger match will include the names of the team and the scorers, and a description of how the team played. The facts are the bones of the Harrovian, but without the flesh and blood of ideas it cannot be made to live. -

Lgï2 C.R4 Price: F2.00 Price Code: B Or Above Who Is Authorised by the Chief Constable to Act As Senior Police Officer for the Purposes of This Order; And

Statutory Document No. 374108 ROAD RACES ACT 1982 THE TOURIST TROPHY MOTORCYCLE RACES ORDER 2OO8 Coming into Operation: I May 2008 In exercise of the powers conferred on The Department of Transport by sections I and 2 of the Road Races Act 19821, and of all other enabling powers, the following Order is hereby made:- Introductory 1. Citation and commencement This Order may be cited as The Tourist Trophy Motorcycle Races Order 2008 and shall come into operation on the 8 May 2008. 2. Interpretation In this Order - "the Act" means the Road Races Act 1982; "the Clerk of the Course" includes, in the absence of the Clerk of the Course, any Deputy Clerk of the Course appointed by the promoter; "closure period" means any period during which an authorisation under article 3 or 4 is in force in relation to the Course or any part of the Course; "the Course" means the roads and property areas specified in Schedule 1; "pedestrian" includes wheelchair users and any persons using another mobility aid other than a bicycle or motor vehicle; "postpone", in relation to a race or practice, includes annulling (declaring void) a race which has already begun; "prohibited area" means the areas listed in Schedule 4 that are not restricted areas; "restricted area" meaÍts the areas listed in Schedule 4 tha| are indicated as being restricted; "senior police officer" means a member of the Isle of Man Constabulary of the rank of sergeant 1 lgï2 c.r4 Price: f2.00 Price Code: B or above who is authorised by the Chief Constable to act as senior police officer for the purposes of this Order; and "signage" means any barrier, sign or structure referred to in article 15 Authorisation to use roads for races etc 3. -

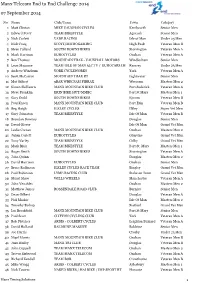

Manx Telecom End to End Challenge 2014 07 September 2014

Manx Telecom End to End Challenge 2014 07 September 2014 No Name Club/Team Town Category 1 Matt Clinton MIKE VAUGHAN CYCLES Kenilworth Senior Men 2 Edward Perry TEAM BIKESTYLE Agneash Senior Men 3 Nick Corlett VADE RACING Isle of Man Under 23 Men 4 Nick Craig SCOTT/MICROGAMING High Peak Veteran Men B 5 Steve Calland SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Storrington Veteran Men A 6 Mark Harrison EUROCYCLES Onchan Veteran Men A 7 Ben Thomas MOUNTAIN TRAX - VAUXHALL MOTORS Windlesham Senior Men 8 Leon Mazzone TEAMCYCLING ISLE TEAM OF MAN 3LC.TV / EUROCARS.IM Ramsey Under 23 Men 9 Andrew Windrum YORK CYCLEWORKS York Veteran Men A 10 Scott McCarron MOUNTAIN TRAX RT Lightwater Senior Men 11 Mat Gilbert 9BAR WRECSAM FIBRAX Wrecsam Masters Men 2 12 Simon Skillicorn MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Port Soderick Veteran Men A 13 Steve Franklin ERIN BIKE HUT/MMBC Port St Mary Masters Men 1 14 Gary Dodd SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Epsom Veteran Men B 15 Paul Kneen MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Port Erin Veteran Men B 16 Reg Haigh ILKLEY CYCLES Ilkley Super Vet Men 17 Gary Johnston TEAM BIKESTYLE Isle Of Man Veteran Men B 18 Brendan Downey Douglas Senior Men 19 David Glover Isle Of Man Grand Vet Men 20 Leslie Corran MANX MOUNTAIN BIKE CLUB Onchan Masters Men 2 21 Julian Corlett EUROCYCLES Glenvine Grand Vet Men 22 Tony Varley TEAM BIKESTYLE Colby Grand Vet Men 23 Mark Blair TEAM BIKESTYLE Port St. Mary Masters Men 1 24 Roger Smith SOUTH DOWNS BIKES Storrington Veteran Men A 25 John Quinn Douglas Masters Men 2 26 David Harrison EUROCYCLES Onchan Senior Men 27 Bruce Rollinson ILKLEY CYCLES RACE -

GD No 2017/0037

GD No: 2017/0037 isle of Man. Government Reiltys ElIan Vannin The Council of Ministers Annual Report Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee .Duty 2017 The Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Piemorials Committee Foreword by the Hon Howard Quayle MHK, Chief Minister To: The Hon Stephen Rodan MLC, President of Tynwald and the Honourable Council and Keys in Tynwald assembled. In November 2007 Tynwald resolved that the Council of Ministers consider the establishment of a suitable body for the preservation of War Memorials in the Isle of Man. Subsequently in October 2008, following a report by a Working Group established by Council of Ministers to consider the matter, Tynwald gave approval to the formation of the Isle of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee. I am pleased to lay the Annual Report before Tynwald from the Chair of the Committee. I would like to formally thank the members of the Committee for their interest and dedication shown in the preservation of Manx War Memorials and to especially acknowledge the outstanding voluntary contribution made by all the membership. Hon Howard Quayle MHK Chief Minister 2 Annual Report We of Man Government Preservation of War Memorials Committee I am very honoured to have been appointed to the role of Chairman of the Committee. This Committee plays a very important role in our community to ensure that all War Memorials on the Isle of Man are protected and preserved in good order for generations to come. The Committee continues to work closely with Manx National Heritage, the Church representatives and the Local Authorities to ensure that all memorials are recorded in the Register of Memorials. -

Etymology of the Principal Gaelic National Names

^^t^Jf/-^ '^^ OUTLINES GAELIC ETYMOLOGY BY THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, Stirwng f ETYMOLOGY OF THK PRINCIPAL GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES |'( I WHICH IS ADDED A DISQUISITION ON PTOLEMY'S GEOGRAPHY OF SCOTLAND B V THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, STIRLING 1911 PRINTKD AT THE " NORTHERN OHRONIOLB " OFFICE, INYBRNESS PREFACE The following Etymology of the Principal Gaelic ISTational Names, Personal Names, and Surnames was originally, and still is, part of the Gaelic EtymologicaJ Dictionary by the late Dr MacBain. The Disquisition on Ptolemy's Geography of Scotland first appeared in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, and, later, as a pamphlet. The Publisher feels sure that the issue of these Treatises in their present foim will confer a boon on those who cannot have access to them as originally published. They contain a great deal of information on subjects which have for long years interested Gaelic students and the Gaelic public, although they have not always properly understood them. Indeed, hereto- fore they have been much obscured by fanciful fallacies, which Dr MacBain's study and exposition will go a long way to dispel. ETYMOLOGY OF THE PRINCIPAI, GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES ; NATIONAL NAMES Albion, Great Britain in the Greek writers, Gr. "AXfSiov, AX^iotv, Ptolemy's AXovlwv, Lat. Albion (Pliny), G. Alba, g. Albainn, * Scotland, Ir., E. Ir. Alba, Alban, W. Alban : Albion- (Stokes), " " white-land ; Lat. albus, white ; Gr. dA</)os, white leprosy, white (Hes.) ; 0. H. G. albiz, swan. -

ORDER 2001 � Coming Into Operation 14Th

Statutory Document No.387/01 THE HIGHWAYS ACT 1986 THE UNMADE HIGHWAYS IN RURAL AREAS (TEMPORARY CLOSURE) (FOOT AND MOUTH DISEASE PRECAUTIONS) (No. 5) ORDER 2001 Coming into operation 14th. June 2001 Expiring on 20th. July 2001 In exercise of the powers conferred on the Department of Transport by section 38(1) of the Highways Act 1986', and of all other enabling powers, the following Order is hereby made: - Citation, commencement and revocation 1. (1) This Order may be cited as the Unmade Highways in Rural Areas (Temporary Closure)(Foot and Mouth Disease Precautions)(No. 5) Order 2001; (2) Subject to the Department of Transport giving public notice in accordance with section 38(3) of the Highways Act 1986 of the making of this Order, this Order shall come into operation on the 14th. June 2001; (3) The Unmade Highways in Rural Areas (Temporary Closure)(Foot and Mouth Disease Precautions)(No.4) Order 2001 2 is revoked upon the coming into operation of this Order. Interpretation 2. In this Order, — "the Access to Land Order" means the Foot and Mouth (Access to Land)(Special Temporary Provisions) Order 2001 3 made on 24th. May 2001 by the Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. 1 1986 c.17 2 SD No.258/01, as amended by SD No.327/01 3 SD No.314/01 Price: £1.60; Price Band B 01.06(c) 1 "agricultural land" has the same meaning 4 as in article 2 of the Access to Land Order "DAFF" means the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry; "the Department" means the Department of Transport; "fenced" means that a fence, wall, hedge or any other feature (e.g. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

School Catchment Areas Order 2O7o

Statutory Document No. 100210 EDUCATION ACT 2OO7 SCHOOL CATCHMENT AREAS ORDER 2O7O Comíng into operøtion L lønuøry 201.0 The Department of Education and Children makes this Order under section 15(a) of the Education Act 2001r. 1 Title This Order is the Sdrool Catchment Areas Order 20L0 and shall come into operation on the l,stlaruary 2011, 2 Commencement This order comes into operation on the l't January 2011 3 Interpretation In this Order "the order maps" means lhreL2maps arurexed to this Order and entitled "Mup No.1 referred to in the School Catchrrrent Areas Order 2010" to "Map No.12 refer¡ed to in the Sclrool Catchment Areas Order 2010 4 Catchment areas of primary schools (1) Úr relation to eadr primary sdrool specified in colrrmn 1 of Sdredule L, the area shown edged with a thick yellow line on one or more of the order maps and indicated by the corresponding nurnber specified in colrrmn 2 of that Sdredule is designated as the catchment area of that sdrool. (2) The parishes constituted for purposes of the Roman Catholic Churdr and annexed to St Anthony's, StJoseph's and StMary's churdres are designated as the catdrment area of St Mary's Roman Catholic School, Douglas. (3) There are no designated catctLment areas for St Thomas' Churdr of England Primary School, Douglas and the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, StJohn's. t 2oo1 c.33 Price: f,2.00 1 5 Catchment areas of secondary schools (1) Subject to paragraphs (2) and (3), in relation to eadr secondary school specified in column 1 of Sdredule 2, the areas designated by article 2 as the catdrment areas of the corresponding primary sdrools specified in column 2 of that Schedule are together designated as the catchment area of that school. -

Buchan School Magazine 1971 Index

THE BUCHAN SCHOOL MAGAZINE 1971 No. 18 (Series begun 195S) CANNELl'S CAFE 40 Duke Street - Douglas Our comprehensive Menu offers Good Food and Service at reasonable prices Large selection of Quality confectionery including Fresh Cream Cakes, Superb Sponges, Meringues & Chocolate Eclairs Outside Catering is another Cannell's Service THE BUCHAN SCHOOL MAGAZINE 1971 INDEX Page Visitor, Patrons and Governors 3 Staff 5 School Officers 7 Editorial 7 Old Students News 9 Principal's Report 11 Honours List, 1970-71 19 Term Events 34 Salvete 36 Swimming, 1970-71 37 Hockey, 1971-72 39 Tennis, 1971 39 Sailing Club 40 Water Ski Club 41 Royal Manx Agricultural Show, 1971 42 I.O.M, Beekeepers' Competitions, 1971 42 Manx Music Festival, 1971 42 "Danger Point" 43 My Holiday In Europe 44 The Keellls of Patrick Parish ... 45 Making a Fi!m 50 My Home in South East Arabia 51 Keellls In my Parish 52 General Knowledge Paper, 1970 59 General Knowledge Paper, 1971 64 School List 74 Tfcitor THE LORD BISHOP OF SODOR & MAN, RIGHT REVEREND ERIC GORDON, M.A. MRS. AYLWIN COTTON, C.B.E., M.B., B.S., F.S.A. LADY COWLEY LADY DUNDAS MRS. B. MAGRATH LADY QUALTROUGH LADY SUGDEN Rev. F. M. CUBBON, Hon. C.F., D.C. J. S. KERMODE, ESQ., J.P. AIR MARSHAL SIR PATERSON FRASER. K.B.E., C.B., A.F.C., B.A., F.R.Ae.s. (Chairman) A. H. SIMCOCKS, ESQ., M.H.K. (Vice-Chairman) MRS. T. E. BROWNSDON MRS. A. J. DAVIDSON MRS. G. W. REES-JONES MISS R. -

Sketches from Manx History (1915)

STEPHEN MILLER CHRISTOPHER SHIMMIN SKETCHES FROM MANX HISTORY (1915) CHIOLLAGH BOOKS FOR CULTURE VANNIN 2020 SKETCHES FROM MANX HISTORY * (1) [5b] The story of the Isle of Man may be divided into three distinct periods—the Celtic, from the unknown past to the 10th century; the Norse, to the middle of the 13th century; and the Manx, to the present time. The story of our Island changes its form as we journey backwards in time. First we have written history, as recorded in State papers and official documents. Overlapping these, and often in conflict with them, we have tradition—a statement of events handed down orally from one generation to the next. Beyond this is Legend—accounts of occurrences passed down through the ages, and usually overlaid with wonder and imagination until it becomes difficult to decide which is truth and which is fancy. Farthest away, in the dim, nebulous beginning of human story telling, we find the most ancient of all records, that of myth. The wonder stories of Egypt, Greece, and Germany, are familiar to many readers, yet how few of us trouble to read the legends of our own race and land. The Celtic mythology is as wonderful, as beautiful, and has more of tenderness than the others. We have marvellous stories of the doings of gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines, druids and magicians, kings and queens, giants and dwarfs, battles of nations, wars with fiends and fairies, adventurous voyages in magic lands and seas, and even under earth and sea. We have beautiful legends of saints and the miracles performed by them; weird stories of witches, stirring battle stories. -

Things to See & Do

APRIL Shops, cafes and pubs Point of Ayre In the picturesque town of Peel, you will find traditional cobbled streets home to small Ayres 2017 independent shops, a post office and banks. There are also plenty of cafes, restaurants and Visitor Centre public houses throughout Peel, look out for those which are ‘Taste’ Accredited. Pick up your A10 Bride free ‘Taste Isle of Man Directory’ from the Sea Terminal. A17 Jurby Head A10 Andreas Jurby Isle of Man Motor Museum Transport Museum A9 A10 A17 A13 Visitor Information St Judes A14 A9 Grove Museum of Victorian Life A13 St Patrick’s Isle Curraghs Ramsey Bay Cruise Welcome Desk Wildlife Park A3 RAMSEY Milntown House Sulby TT COURSE Centrally located within the Sea Terminal and manned for each Cruise Ship call from April Ballaugh Glen Elfin A14 A15 Maughold to the end of September, Welcome Volunteers are on-hand to offer friendly local advice and 7 Sulby Glen Ballaugh Glen Maughold Head Bishopscourt Glen guidance, point you in the right direction of where you can purchase Go-Explore passes and A.R.E. Motorcycle Museum A2 Kirk Michael TT COURSE Manx National Heritage Site passes, as well as offering the independent traveller valuable Glen Wyllin Snaefell A18 Glen Mona Ballaglass Glen Glen Mooar Port Cornaa and expert advice on what to see and do, and how to get there – all free of charge. Tourism Tholt-y-Will Glen A4 literature, maps, Taste Guides and more, are also available from the desk. Fenella Beach A14 S na ef el A3 l M ou nta in R ail way Dhoon Glen AD A4 RO Cronk-y-Voddy A2 EY Welcome Centre MS RA St Patrick’s Isle LAXEY 4 TT COURSE The Welcome Centre is a one-stop shop for all visitor information - offering a range of tourism A PEEL Great Laxey Wheel Glen Helen Peel Castle Great Laxey Mine Railway literature, maps, sale of tickets, general Island-wide advice and local crafts and produce.