A Picture of a Rice Cake’ (Gabyō)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appetizers Soups 16 Flatbreads Charcuterie Board

Lunch Appetizers Grilled Wagyu Angus Ribs 32 Classic Caesar Salad 15 lemongrass-ginger-soy marinade crisp romaine hearts, garlic croutons, creamy anchovy & garlic dressing Boston Lettuce With Beefsteak Tomatoes 18 toasted sunflower seeds, sliced vidalia onions, Atlantic Salmon Tartar 22 beef fry & creamy jalapeno ranch dressing horseradish, capers, avocado & yucca chips Belgium Endives, Radicchio & Arugula Salad 24 House Made Lamb Mergeuz Sausage 20 bresoala, caramelized local pears, spiced pecans caramelized onions, beef "bacon", potatoes & red wine vinaigrette & whole grain mustard Liver Mousse on Crispy Rice Cake 19 PG Signature Beef Jerky 26 onion jam & black truffles our traditional house-smoked beef jerky House Smoked Wild Organic King Salmon 18 grilled asparagus, poached egg, crispy shallots & truffle oil The Prime Grill Salad 16 crisp romaine, red & yellow tomatoes, cucumbers, garlic croutons & onions tossed in a citrus-cumin vinaigrette Soups 16 Soup Du Jour Grandma Bella’s Chicken Noodle Soup Roasted Corn Chowder freshly made daily traditional warm chicken broth potatoes & peppers, beef "bacon", with a mélange of seasonal vegetables creamy finish Charcuterie Board Selection of Three 25 Selection of Five 34 Choose from: pepperoni bresaola, dried beef salami, dried veal salami, dried lamb salami, duck prosciutto, duck capicola, chorizo & truffled chorizo served with cornichons, hot pickled cherry peppers, whole grain french mustard & toasted baguette Flatbreads baked to order in our wood-fired oven Salami Flatbread 22 Duck Bolognese -

Pisco Y Nazca Doral Lunch Menu

... ... ··············································································· ·:··.. .·•. ..... .. ···· : . ·.·. P I S C O v N A Z C A · ..· CEVICHE GASTROBAR miami spice ° 28 LUNCH FIRST select 1 CAUSA CROCANTE panko shrimp, whipped potato, rocoto aioli CEVICHE CREMOSO fsh, shrimp, creamy leche de tigre, sweet potato, ají limo TOSTONES pulled pork, avocado, salsa criolla, ají amarillo mojo PAPAS A LA HUANCAINA Idaho potatoes, huancaina sauce, boiled egg, botija olives served cold EMPANADAS DE AJí de gallina chicken stew, rocoto pepper aioli, ají amarillo SECOND select 1 ANTICUCHO DE POLLO platter grilled chicken skewers, anticuchera sauce, arroz con choclo, side salad POLLO SALTADO wok-seared chicken, soy and oyster sauce, onions, tomato wedges, arroz con choclo, fries RESACA burger 8 oz. ground beef, rocoto aioli, queso fresco, sweet plantains, ají panca jam, shoestring potatoes, served on a Kaiser roll add fried egg 1.5 TALLARín SALTADO chicken stir-fry, soy and oyster sauce, onions, tomato, ginger, linguini CHICHARRÓN DE PESCADO fried fsh, spicy Asian sauce, arroz chaufa blanco CHAUFA DE MARISCOS shrimp, calamari, chifa fried rice DESSERTS select 1 FLAN ‘crema volteada’ Peruvian style fan, grilled pineapple, quinoa tuile Alfajores 6 Traditional Peruvian cookies flled with dulce de leche SUSPIRO .. dulce de leche custard, meringue, passion fruit glaze . .. .. .. ~ . ·.... ..... ................................................................................. traditional inspired dishes ' spicy ..... .. ... Items subject to -

Chinese New Year Special

CHINESE NEW YEAR SPECIAL Hometown Charcuterie Plate ! 红红火火 Seared house made Szechuan style dry-cured pork sausage and bone-in rib sausage 18 Crispy Lotus Root Sandwich 招财进宝- Lotus root, shrimp, pork, ginger, scallion, bread crumbs 15 Marinated Pork Ear in Avocado Chili Oil ! 诸事顺利- Pork ear, onion, cucumber, avocado, lime, chili pepper, cilantro 15 Kung Pao Taro with Lily Bulbs ! 金玉满堂- Taro, lily bulb, scallion, chili pepper, Szechuan pepper 15 House-made Shrimp Ball and Egg Dumpling Stew 阖家团圆- Shrimp, cilantro, egg, pork, scallion, ginger, 20 Hao Noodle and Tea West Village Appetizer Ginger Spinach V Steamed spinach, fresh ginger sauce, served cold 8 Bean Curd in Chili Oil !V Soybean curd, chili oil, Szechuan pepper, sesame, cilantro 8 Wood Ear Mushroom Salad !V Black wood ear mushroom, fresh spicy red pepper, scallion, vinegar 8 Sweet and Sour Ribs Pork baby ribs, caramelized sweet soy sauce, rice vinegar 12 Smoked Fish Fried sole fish filet, smoked sweet soy sauce 12 Chicken Salad in House Special Chili Oil !! Steamed organic boneless chicken in spiced oil, cucumber, cilantro, garlic, ginger, scallion, peanut, sesame, soy sauce, vinegar 20 *All-nature high-quality chicken from Pennsylvania Dim Sum Soup Dumpling (4) Pork, ginger, sesame oil 8 Steamed Dumplings (6) Options: Pork and Cabbage / Egg and Chive Pork, cabbage, egg, chive, ginger, sesame oil / 8 Siu Mai (4) Sticky black rice, bacon, mushroom 8 Pan Seared Dumplings (4) Pork, chicken stock, shrimp, scallion, ginger, sesame oil 8 Pan Seared Egg and Chive Bun (1) Egg, -

Micro Food Station Menu

PACKAGE Micro Food Station Menu PASSED HORS D’OEUVRES *Please select up to six of the following: V E G E T A R I A N PEA AND TRUFFLE RISOTTO CAKES Roasted Garlic Aioli, Purple Basil Cress WILD MUSHROOM RISOTTO CAKES with Lemon Garlic Aioli and Fresh Chive AGED WHITE CHEDDAR GRILLED CHEESE with Smoked Tomato Jam PARMESAN CRISPS with Avocado-Tomato Salsa and Coriander Cress (*Gluten Free) BLACK TRUFFLED MAC ‘N CHEESE with Cave-Aged Gruyere, Farmhouse White Cheddar, Parmigiano-Reggiano and Herbed Bread Crumbs served in Mini Bamboo Cups MINI CRISPY FALAFEL CROQUETTE Cucumber-Tomato-Parsley Taboulleh, Beet-Pickled Radish, Spicy Chickpea Hummus (*Vegan) ARTISAN FLATBREAD “MARGHERITA” PIZZA with Fior di Latte Mozzarella, Fresh Basil and San Marzano Tomatoes Vegetarian Passed Hors D’Oeuvres Cont. on Page 2 1 BANGKOK FRESH ROLL Thai Basil, Coriander, Mint, Nori, Cucumber, Carrot, Mango, Avocado, Daikon, Rice Noodles, Pickled Ginger, Peanut-Chili Dipping Sauce (*Vegan/Gluten Free/Contains Nuts) VEGETARIAN SPRING ROLL Carrots, Taro, Mung Bean Noodles, Tofu, Shiitake & Woodear Mushrooms, Soy-Chili Dipping Sauce MISO-GLAZED JAPANESE EGGPLANT served on a Sushi Rice Cake with Heirloom Radish-Fennel Slaw (*Vegan) ARTISAN FLATBREAD with Wild Mushrooms, San Marzano Tomatoes, Mozzarella, Pecorino Romano and Parmigiano-Reggiano, Parsley Chiffonade HEIRLOOM TOMATO-GOAT CHEESE TARTLET Crispy Phyllo, Roasted Pistachio Crumble, Purple Basil Cress (*Contains Nuts) CARAMELIZED VEGETABLE TOSTADA Ancho Chili Roasted Vegetables, Black-Beans, Charred Corn, Kale-Pickled -

Yeomiji Menu 14

여 미 YEOMIJI 지 Korean BBQ Restaurant APPETIZERS 물만두 Steamed Dumplings 9 두부전 Seared Tofu (v, gf) 8 Steamed homemade dumplings filled with Pan-seared tofu, served with house soy sauce kimchi, tofu, bean sprouts and beef 잡채 Japchae Noodles (v, gf) 15 만두구이 Fried Dumplings 9 Potato glass noodles sautèed with spinich, carrots Pan-fried homemade dumplings filled with and ear mushrooms tofu, zucchini, carrots, mushrooms and glass noodles Choice of beef or vegetarian (v) 떡볶이 Spicy Rice Cakes (v, gf, s) 14 Rice cake sautéed with vegetables in chili sauce 새우 슈마이 Shrimp Shumai 6 Optional addition of hard boiled eggs Steamed miniature wontons filled with shrimp 호박죽 Squash Soup (v, gf) 9 닭날개 Crispy Wings 12 Kabocha squash soup topped with dried dates Battered crispy chicken wings glazed with and pine nuts garlic soy sauce 에다마메 Edamame (v, gf) 6 파전 / 김치, 야채, 해물 Korean Pancakes 13 Baby soy beans steamed and lightly salted Korean pancake with choice of kimchi (v,) (add $2), assorted vegetables (v), or seafood (add $3) SALADS 연어 샐러드 Salmon Salad (gf) 17 아보카도 망고 샐러드 Avocado Mango Salad (v, gf) 15 Mixed greens, salmon sashimi and avocado with Mixed greens, avocado, mango, sun-dried ginger dressing raisins with plum sauce KOREAN TACOS Three palm sized soft corn tortillas with lettuce, scallion, tomato-onion-avocado salsa with choice of topping 갈비 Kalbi 15 닭구이 Chicken 14 소불고기 Beef Bulgogi 14 양념닭 Spicy Chicken (s) 14 돼지불고기 Spicy or Non-Spicy Pork 14 야채 Bean Sprouts and Spinach (v, gf) 13 김치불고기 Kimchi Pork (s) 14 If you have any allergies or dietary restrictions, -

Stir-Fried Rice Cake

Stir-Fried Rice Cake A delicious and typical Shanghai dish made with chewy rice cakes stir fried together with vegetables and meat, although very popular during Chinese New Year it has been a daily and regular dish on our table. If you never had this rice cake you are missing out…I can guarantee that once you try, it will be your favorite… – What is Asian rice cake? This is not your usual rice cake, the ones that you find in the cracker section of the supermarket…this are made of a mix of regular rice and glutinous rice flour. The rice cake is opaque and hard when you buy them, and soften once cooked, and have a nice chewiness. If you like chewy texture you will definitely love these little bites of rice loaded with the broth flavor and packed with lots of vegetables and meat such as pork or chicken. – Where can I find rice cake? These rice cake can be found in Asian market as they are very popular in Korean cuisine as well. They are usually in the refrigerator section. They come in various shape, as a stick, peanut shape of sliced. – How can I cook rice cake? First you need to soak the rice cake for a few minutes and separate them. Drain the water and then boil in water. Many recipes skip the boiling part as they add the drained rice cake directly to the stir-fried. I prefer to boil first as give the final dish a less stick together… – Ready to give this Asian rice cake a try? Ingredients: 300 g pork loin, cut into strips (or chicken if you prefer) 4 garlic cloves, finely minced 2 teaspoons cornstarch 1 tablespoon soy sauce 1 tablespoon olive oil Salt and pepper to taste 2.2 lbs ( 1kg) rice cakes 1 medium size napa cabagge, sliced 4-5 dried shiitake mushrooms, soaked in warm water and sliced 1 small onion, thinly sliced 4-5 green onion, cut into 1 inch length 1 tablespoon oil 1 tablespoon soy sauce 1 tablespoon oyster sauce ½ tablespoon sugar 1 tablespoon cooking wine Ground white pepper and salt to taste Method: Slice the pork into strips and add the garlic, salt, pepper, corn starch and oil. -

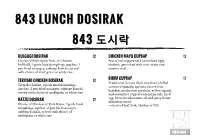

843 Lunch Dosirak

843843 LUNCHLUNCH DOSIRAKDOSIRAK 843843 도시락도시락 BULGOGI DOSIRAK 12 CHICKEN MAYO CUPBAP 12 Choice of Beef, Spicy Pork, or Chicken Bed of rice topped with scrambled eggs, BulGoGI, 2 pork fried dumplings, japchae, 2 chicken, garnished with nori, mayo and pan fried sausages, cabbage kimchi, served sesame seed. with choice of multigrain or white rice BIBIM CUPBAP 12 TERIYAKI CHICKEN DOSIRAK 12 Traditional Korean Style rice bowl, chilled Teriyaki chicken, 2 pork fried dumplings, seasoned spinach, sprouts, carrot, fern japchae, 2 pan fried sausages, cabbage kimchi, bracken, mushroom zucchini, yellow squash, served with choice of multigrain or white rice and cucumber topped with sunny side fried egg. Served with sesame oil and spicy house KATZU DOSIRAK 12 BiBimBap sauce. Choice of Chicken or Pork Katzu, 2 pork fried – choice of Beef, Pork, Chicken, or Tofu dumplings, japchae, 2 pan fried sausages, cabbage kimchi, served with choice of multigrain or white rice ããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããããã"843" Happy Hour Tuesday - Saturday 3pm to 7pm, Excluding Holidays ALL DRAUGHT BEER $1 OFF Domestic Beer by Bottle $2 Angry Orchard, Bud Light, Bud Light Lime, Bud Light Orange, Budweiser, Coors Light, Michelob Ultra, Miller Lite, Sam Adams, Yuengling, Blue Moon Import Beer $3 Lucky Buddha, Asahi, Kirin Ichiban, Tiger, Chang, Stella Artois, Heineken Guinness, -

Menu Kayumanis Seaside Indonesian Intimate Bistro with Image.Indd

Kayumanis Seasidestylish Indonesian Sanur bistro Sindhu Beach, Sanur Bali, Indonesia 62 361 6200 777 Kayumanis Seaside Sanur @kayumanisseasidesanur Indonesian Appetizer TUNA JERUNGGA seared tuna with fresh pamelo, tamarind sauce, crispy garlic and water cress Rp 55.000 GADO-GADO GULUNG assorted steamed vegetables rolls, fried tofu, bean curd, potato, tomato, boil egg, crackers with peanut sauce Rp 45.000 UDANG SAMBAL MATAH Grilled prawn tossed with lemon grass chili sauce and fresh local salad Rp 55.000 RANJUNGAN SERANGAN crispy crab soft shell salad with water cress, roasted capsicum, sweet cord and sweet chili dressing Rp 60.000 All prices are subject to 16.6 % government tax and service charge Soup SOP BUNTUT Indonesian traditional oxtail soup with green bean, potato, tomato, celery and crispy emping Rp 65.000 SOTO AYAM Indonesian favorite chicken soup with glass noodles, shredded chicken, tomato, celery, boil egg and crispy potato Rp 55.000 BAKWAN SURABAYA Surabaya style beef ball soup with beef rib, glass noodles, siomay, tofu, celery and crispy shallot Rp 40.000 SEAFOOD SEGARA ENING Balinese seafood soup with cucumber, tomato and basil Rp 55.000 SOUP BALUNG JUKUT JEPANG pork ribs soup with squash vegetables , tomato and crispy shallot Rp 40.000 All prices are subject to 16.6 % government tax and service charge Salad CLASIC CAESAR SALAD Crunchy baby romaine, with smoked chicken, eggs, shave parmesan, crispy bacon, baguette crouton and caezar dressing Rp 65.000 GRILLED NICOISE TUNA vegetables salad with seared tuna, boil egg, olive -

Conjosé Restaurant Guide the 60Th World Science Fiction Convention

ConJosé Restaurant Guide The 60th World Science Fiction Convention McEnery Convention Center San José, California Codes Used in this Guide Distance: Amounts: A Short walk $ Cheap B Walking distance $$ Reasonable C Car required $$$ Expensive D Long car ride $$$$ Very expensive E In another city Codes: B Breakfast NCC No Credit Cards BW Beer & Wine Only NR No Reservations D Dinner OS Outdoor Seating DL Delivers PP Pay Parking FB Full Bar R Romantic FP Free Parking RE Reservations Essential GG Good for Groups RL Reservations Recommended IWL Impressive Wine List for Large Parties KF Kid Friendly RR Reservations Recommended L Lunch SF Smoke Free TO Take Out LL Open Late (11:00 PM) TOO Take Out Only LLL Open Very Late (12:30 AM) LM Live Music VP Valet Parking ConJosé Restaurant Guide The 60th World Science Fiction Convention 29 August through 2 September 2002 McEnery Convention Center San José, California Karen Cooper & Bruce Schneier Restaurant Guide Reviews by Karen Cooper and Bruce Schneier Cover Art: David Cherry Copyediting & Proofreading: Beth Friedman Layout & Design: Mary Cooper © 2002 San Francisco Science Fiction Conventions, Inc., with applicable rights reverting to creators upon publication. “Worldcon,” “World Science Fiction Convention,” “WSFS,” “World Science Fiction Society, “NASFIC,” and “Hugo Award” are registered service marks of the World Science Fiction Society, an unincorporated literary society. ConJosé is a service mark of San Francisco Science Fiction Conventions, Inc. Table of Contents Welcome ......................................................................................................7 -

Gluten Free Products

Gluten Free Products Natural Foods Department q Amy’s Stir Fry Thai Organic q q 1-2-3 Gluten Free Sugar Cookie Mix Amy’s Tamale Pie Organic q q 1-2-3 Gluten Free Muffin Mix Annie’s BBQ Sauce Hot Chipotle q q 1-2-3 Gluten Free Pan Bar Mix Annie’s BBQ Sauce Original q q Annie Chun Rice Express Sprout Brown Rice Annie’s BBQ Sauce Smokey Maple q q Annie Chun Rice Express Sticky White Rice Annie’s BBQ Sauce Sweet & Spicy q q American Health Acidophilus Chew Blueberry Annie’s Dressing Artichoke Parmesan q q American Health Acidophilus Chew Strawberry Annie’s Dressing Balsamic Vinaigrette q q Blue Diamond Almond Breeze Vanilla Unsweetened Annie’s Dressing Cowgirl Ranch q q Blue Diamond Almond Breeze Chocolate Unsweetened Annie’s Dressing Italian q q Blue Diamond Almond Breeze Original Unsweetened Annie’s Dressing Raspberry Vinaigrette q q Blue Diamond Almond Breeze Vanilla Annie’s Dressing Roasted Red Pepper q q Blue Diamond Almond Breeze Chocolate Annie’s Ketchup Organic q q Blue Diamond Almond Breeze Original Annie’s Mustard Dijon Organic q q Amy’s Organic Chili w/ Vegetables Annie’s Mustard Horseradish Organic q q Amy’s Soup Chunky Tomato Bisque Organic Annie’s Mustard Yellow Organic q q Amy’s Soup Chunky Vegetable Organic Annie’s Organic Dressing Buttermilk q q Amy’s Soup Lentil Vegetable Organic Annie’s Organic Dressing Green Garlic q q Amy’s Soup Organic Cream of Tomato Annie’s Organic Dressing Papaya Poppy q q Amy’s Soup Organic Split Pea Annie’s Organic Dressing Roasted Garlic Vinaigrette q q Amy’s Soup Organic Black Bean Annie’s Gluten -

The Peranakan Culinary Journey an INTRODUCTION to PERANAKAN CUISINE

as renowned for its peranakan cuisine as it is for its historical attractions, a visit to malacca would be incomplete without sampling the city’s plethora of ambrosial culinary offerings. History, Culture & Cuisine & Culture History, The Peranakan Culinary Journey AN INTRODUCTION TO PERANAKAN CUISINE In the 15th century, the Princess Hang Li Po of China arrived in Malacca to be wed to Sultan Mansur Shah. Their union was the beginning of many inter-marriages between the Chinese men from her entourage to the beautiful local Malay women. Descendents of these unions later became known as the ‘Peranakan’ people. This unique blending of cultures meant a melding of the best of Chinese cooking techniques and the Malay use of spice and herbs, creating one of South East Asia’s most original and exotic cuisines. The complexities of Peranakan dishes meant hours of painstaking preparation in the olden days, when women would gather in the kitchen just after dawn to work on the midday meal, making it a ritual not just for cooking but also for bonding. Spices were to be roasted then pounded with plump chillies, galangal and shallots into smooth pastes, lemongrass bruised, lime leaves sliced into thin, hair-fine shreds. These days modern appliances make Peranakan cooking far easier, without compromising on taste. THE PERANAKAN CULINARY JOURNEY Delve into the intricacies of authentic Peranakan cuisine with a cooking class hosted by our Peranakan Master Chef. Experience an introduction to the aromatic ingredients contributing to each speciality, followed by a lesson that will give you insight into the history of each exquisite dish, leaving you with a satiated belly and classic recipes to take home with you. -

The Diversity of Traditional Malay Kuih in Malaysia and Its Potentials

Kamaruzaman et al. Journal of Ethnic Foods (2020) 7:22 Journal of Ethnic Foods https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-020-00056-2 REVIEW ARTICLE Open Access The diversity of traditional Malay kuih in Malaysia and its potentials Mohd Yusof Bin Kamaruzaman1,2, Shahrim Ab Karim2* , Farah Adibah Binti Che Ishak2 and Mohd Mursyid Bin Arshad3 Abstract Malaysia is synonymously known as a multicultural country flourished with gastronomic nuances in abundance. Within the multitude of well-known savory foods available through the history of Malaysia, kuih has always bestowed a special part in the Malaysian diet. Kuih houses varying types of delicacies ranging from sweets to savory treats or snacks. As with its counterparts in the Malay cuisine, kuih has also been influenced by many historical events led by the migration of Chinese, Indians, and other explorers or visitors to Malaysia in the olden days. This casually developed the Malay kuih which now coined as the traditional Malay kuih; traditional as in the way that the classical values and authenticity were respected and established then. As time progresses and changes the lifestyle of Malays, newly innovated products are at the rise and emerged another type of kuih with somewhat similar characteristics to that of traditional Malay kuih, namely Nyonya Kuih. Nyonya kuih noted to be a reformulation of traditional Malay kuih with native Chinese expertise through some tweaks inculcating their palates and culinary library. Further along, the modernization also impacted the traditional Malay kuih in such a way that the overall representations being put at stake of unclear identity through innovations and industrializations.