Argentina’S New Government Issues Controversial Decrees Andrã©S Gaudãn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Gabinete De Macri

El Gabinete de Macri Equipo de trabajo: Ana Rameri Agustina Haimovich Alejandro Yoel Ventura Responsable General: Ana Rameri Coordinación: Claudio Lozano Tomás Raffo Diciembre 2015 1 El gabinete de Macri es la muestra más evidente del desembarco del gran empresariado en el gobierno. Si bien actualmente existe discusión en torno al tipo de vínculo que debe establecerse entre los funcionarios del Estado con el sector empresario para favorecer un sendero de desarrollo, hay un consenso bastante amplio acerca de los riesgos que para el desarrollo económico, para la inclusión social y para la democratización de la vida política que implica la colonización por parte de las fracciones del capital concentrado del aparato estatal. La historia argentina tiene pruebas suficientes acerca de la existencia de estos nexos estrechos y las implicancias nocivas que tienen para el desarrollo y el bienestar del pueblo. El enraizamiento del sector privado sobe el aparato del Estado tiene un denominador común que atraviesa históricamente los distintos ciclos de acumulación y que se trata del afán de la burguesía local por la obtención de rentas de privilegio, (muy alejadas de lo que en la literatura económica se conoce como las rentas tecnológicas schumpeterianas de carácter transitorias), y más asociadas al carácter parasitario de corporaciones empresarias que se expanden al calor de los recursos públicos y la protección del estado. Los aceitados vínculos entre las fracciones concentradas del capital y los militares del último gobierno de facto posibilitaron el surgimiento de lo que se conoció como la “Patria Contratista” que derivó en espacios privilegiados para la acumulación de capital. -

Centro Estratégico Latinoamericano De Geopolítica Informe Apuntes

Centro Estratégico Latinoamericano de Geopolítica Informe Apuntes sobre el gabinete económico de Mauricio Macri Por Agustín Lewit y Silvina M. Romano Tal como se esperaba, el gabinete de ministros que acompañará a Mauricio Macri en su presidencia tiene una fuerte impronta neoliberal, pro-mercado y empresarial. Previo a la asunción formal, varios de los ministros realizaron acciones que preanuncian lo que será el rumbo económico del gobierno entrante. Al respecto, alcanza con mencionar tres de ellas: 1) La conversación que mantuvo el flamante ministro de Hacienda argentino, Alfonso Prat-Gay, con el secretario del Tesoro estadounidense, Jacob Lew, al cual le adelantó las líneas macroeconómicas del futuro gobierno, antes de que el mismo las haga explícita en el propio país; 2) la reunión del flamante secretario de Finanzas de Argentina, Luis Caputo, con representantes de los fondos buitre para avanzar en un posible acuerdo entre las partes; y, 3) los anuncios de la flamante canciller argentina, Susana Malcorra respecto a que “el ALCA no es una mala palabra”, haciendo alusión a la posible futura firma de un TLC con EEUU. En líneas generales, una devaluación de la moneda, sumada a una mayor apertura comercial y a la toma de deuda son las coordenadas que marcarán el nuevo rumbo económico del país. Vale la pena recordar que la devaluación implica, básicamente, la licuación de los ingresos de los asalariados y una transferencia de riqueza hacia los sectores con capacidad para dolarizar sus activos, generalmente grande firmas locales y multinacionales. Esto ayuda a comprender en buena medida el grupo de gente seleccionada para los ministerios. -

Fuerte Ofensiva Del Gobierno Y La Corte Contra Los Trabajadores

Caetano: «Me interesa que el AFA: lo único claro es En sólo dos meses desalojaron lenguaje del cine que Angelici suma poder a 64 familias en La Boca sea popular» Domingo 26.2.2017 BUENOS AIRES AÑO 7 Nº 2106 EDICIÓN NACIONAL PRECIO $ 35 RECARGO ENVÍO INTERIOR $ 3 www.tiempoar.com.ar/asociate [8-10] FLEXIBILIZACIÓN LABORAL AVanZADA JUDICIAL A Una SEMana DEL PARO DOCENTE Y LA MARCHA DE LA CGT Fuerte ofensiva del gobierno y DOM 26 la Corte contra los trabajadores » El máximo tribunal estableció que los estatales ya no podrán » A eso se suman pedidos de juicio político a magistrados que defenderse en el Fuero Laboral. El fallo debilita a los asalariados y obligan a cumplir acuerdos paritarios y sentencias que pretenden establece un antecedente peligroso. El Consejo de la Magistratura imponer límites al derecho constitucional de huelga. La apura una auditoría para presionar al fuero. Por Martín Piqué respuesta del juez Arias Gibert. Por Alfonso de Villalobos edgardo GÓMEZ [3-5] ALLANARON LA SECRETARÍA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS «No voy Sospechosa «pérdida» de a dejar de 140 legajos de presos políticos cultivar, Eran documentos clave para tramitar la reparación histórica a los ya no sobrevivientes de la dictadura. Avruj intentó minimizar el escándalo. Milani, a un paso de ser procesado por la causa Ledo. Por Pablo Roesler pueden mentirnos [13] BLINDAJE MEDIÁTICO [7] ESPIONAJE [15] CANDIDATURAS más» Millonario La Justicia El peronismo Entrevista a Adriana regalo a ignoró la se reagrupa Funaro, la cultivadora Clarín en un denuncia con un ojo en de cannabis para uso medicinal que estuvo año electoral de Hebe las encuestas presa y hoy cumple El Enacom habilitó la Archivaron la causa por Los gestos de unidad prisión domiciliaria. -

RESTRICTED WT/MIN(17)/SR/1 19 February 2018 (18-1068) Page: 1/2 Ministerial Conference Eleventh Session Buenos Aires, 10-13 Dece

RESTRICTED WT/MIN(17)/SR/1 19 February 2018 (18-1068) Page: 1/2 Ministerial Conference Eleventh Session Buenos Aires, 10-13 December 2017 SUMMARY RECORD OF THE OPENING SESSION HELD AT THE EXHIBITION CENTRE OF THE CITY OF BUENOS AIRES SUNDAY, 10 DECEMBER 2017 AT 4.15 P.M. Chairperson: Her Excellency Ms Susana Malcorra (Argentina) Subjects discussed: 1 WELCOMING REMARKS BY THE CHAIRPERSON ........................................................... 1 2 PART 1 OF THE OPENING SESSION ............................................................................. 1 2.1 Adoption of the Agenda ................................................................................................ 2 3 PART 2 OF THE OPENING SESSION ............................................................................. 2 3.1 Address by the Director-General and Statements by Heads of State................................... 2 1 WELCOMING REMARKS BY THE CHAIRPERSON 1.1. The Chairperson welcomed everyone to the Eleventh Session of the Ministerial Conference of the WTO and to Buenos Aires. 1.2. She thanked all Heads of Delegation and delegates for their presence. She also thanked Members for having entrusted Argentina to host MC11, and for having appointed her as the Chairperson of the Conference. She extended her gratitude to Uruguay for its cooperation in ensuring that the Eleventh Ministerial Conference could take place in Buenos Aires. She was also grateful to the three Vice Chairpersons of the Ministerial Conference who would assist her during the following days: H.E. Dr Okechukwu Enelamah of Nigeria; H.E. Mr David Parker of New Zealand and Mr Edward Yau of Hong Kong, China. 1.3. She briefly explained that the first part of the Opening Session would comprise the address by the Chairman of the General Council and the adoption of the agenda. -

El Macrismo Presentó a Los Funcionarios De Su Gabinete

Jueves 26.11.2015 BUENOS AIRES MIN MÁX AÑO 6 Nº 1996 18º 27º EDICIÓN NACIONAL PRONÓSTICO PRECIO $ 15 CAPITAL FEDERAL ENVÍO AL INTERIOR + $ 1,50 MARIANO ESPINOSA [3-6] POLÍTICA LO ANUNCIÓ MARCOS PEÑA EN CONFERENCIA DE PRENSA «No es lo mismo un país que una empresa, que El macrismo nadie se confunda» presentó a los funcionarios de su Gabinete » La sorpresa es la continuidad de Barañao. De Andreis irá a la Secretaría General de la Presidencia, Sturzenegger Cristina lo definió al Banco Central, Cano al Plan Belgrano, Abad a la AFIP, acompañada por los Lombardi a Medios Públicos y De Godoy a la AFSCA. Aún gobernadores JUE26 en la inauguración de no se confirmó quién será ministro de Trabajo. obras en el Hospital Posadas y ratificó » Scioli recibió a la electa gobernadora Vidal en La Plata que velará por las para avanzar en la transición. Las claves del encuentro. conquistas logradas. Otra masiva Jefe de Gabinete Hacienda y Finanzas Marcos Peña Alfonso Prat-Gay marcha en Interior: Agricultura: Defensa: reclamo de Rogelio Frigerio Ricardo Buryaile Julio Martínez NiUnaMenos Educación: Energía y Minería: Turismo: Esteban Bullrich Juan José Aranguren Gustavo Santos Más de 50 mil Transporte: Modernización: Cultura: personas se Guillermo Dietrich Andrés Ibarra Pablo Avelluto manifestaron desde Congreso hasta la Cancillería: Desarrollo Productivo: Comunicaciones: Plaza de Mayo. Susana Malcorra Francisco Cabrera Oscar Aguad Desarrollo Social: Seguridad: Salud: Carolina Stanley Patricia Bullrich Fernando de Andreis Ciencia y Tecnología: Justicia: Medio Ambiente: Lino Barañao Germán Garavano Sergio Bergman Polémica por los dichos de Abel Albino El pediatra, uno de los referentes en Salud de Cambiemos, ESPECTÁCULOS rechazó el uso del preservativo para prevenir el VIH. -

12 April 2012

UN General Assembly Informal Thematic Debate on Disaster Risk Reduction 12 April 2012 North Lawn Building Conference Room 2 46th Street at First Avenue UN Headquarters, New York Agenda ‐ Speakers’ Biographies ‐ Concept Note Organized in cooperation with UNISDR, DESA, OCHA, UNEP, UNESCO, UNHabitat, Permanent Mission of Australia to the United Nations, Permanent Mission of the Republic of Indonesia to the United Nations, Permanent Mission of Japan to the United Nations, and Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations 2 TIME PROGRAMME – CONFERENCE ROOM 2 (NLB) 10am – 10:45am OPENING SESSION H.E. Mr. Nassir Abdulaziz Al‐Nasser, President of the General Assembly Ms. Susana Malcorra, Under‐Secretary‐General, Chef de Cabinet of the United Nations Secretary‐General (delivering remarks on behalf of H.E. Mr. Ban KiMoon, United Nations SecretaryGeneral) H.E. Mr. Willem Rampangilei, Deputy Coordinating Minister for People’s Welfare of the Republic of Indonesia (delivering remarks on behalf of H.E. Mr. Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, President of the Republic of Indonesia, UNISDR Global Champion for Disaster Risk Reduction) Senator The Hon. Bob Carr, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Australia (delivering remarks on behalf of the Group of Friends of Disaster Risk Reduction) H.E. Mr. Joe Nakano, Parliamentary Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs of Japan 10:45am – 1 pm INTERACTIVE PANEL DISCUSSION I: ADDRESSING URBAN RISK THROUGH PUBLIC INVESTMENT Moderated by Ms. Margareta Wahlström, Special Representative of the Secretary‐General for Disaster Risk Reduction Introduction: Understanding urban risk today and projections for tomorrow High‐level expert addressing each of the following sub‐themes: Making cities resilient Mr. -

Reverberations of the Trump Effect in the Global South María V

Struggles over Rights and Representations in the Migrant Metropolis: Reverberations of the Trump Effect in the Global South María V. Barbero While Latin America figures in US debates about immigration as a source of immigrants, Trump- style anti-immigrant politics have gained a following in Latin American countries as well. María Barbero examines rhetoric and resistance in Argentina. It is 5:30 in the afternoon on November 22, 2016, and the sun is beaming on the faces of about 500 of us marching from Avenida de Mayo to the congressional palace in Buenos Aires. I am surrounded by flags of Bolivia, Paraguay, Senegal, and Brazil, the LGBTQ rainbow flag, the multicolor Whiphala flag representing indigenous communities of the Andes, and a number of popular and labor party flags. All have joined a march organized by the Red Nacional de Migrantes y Refugiados en Argentina (National Network of Migrants and Refugees in Argentina; red means “network” in Spanish) against “the xenophobic and discriminatory politics of [Mauricio] Macri’s government”1 (Red Migrante 2016). The march comes in the wake of a number of shifts in the Argentine state’s official approach to immigration policy and heightened anti-immigrant rhetoric in public discourse. Flyers advertising the event and chants at the march announce the main messages: migration is a human right; halt plans for a detention center for migrants in Buenos Aires; stop xenophobia and racism. While many are unsure about whether Donald Trump knows much about Argentina, they are deeply aware of his anti-immigrant sentiments and have strategically placed him at the center of their messages as they mobilize to protect migrant rights and make claims to the migrant metropolis.2 Trump effects: criminalization of immigrants and discourses of the border Argentina’s immigration policy is arguably one of the most progressive in the world. -

Argentina's Road to Recovery

Argentina’s Road to Recovery By Roger F. Noriega December 2015 KEY POINTS • Mauricio Macri, who will become Argentina’s president on December 10, is moving decisively to apply free-market solutions to restore his country’s prosperity, solvency, and global reputation. • Success of Macri’s center-right agenda could serve as an example for many Latin American countries whose statist policies have produced ailing economies and political instability. • As Argentina recovers its influence in favor of regional democracy and human rights, the United States must step forward to support these causes in the Americas. he November 22 election of Mauricio Macri, a incumbent, but many Peronists who rejected the Kirch- Tcenter-right former Buenos Aires mayor and busi- ners’ heavy-handed tactics ended up giving Macri the ness executive, as president of Argentina presents a votes he needed to win the presidency.3 pivotal opportunity to vindicate free-market economic Because the results were much closer than pre-election policies and rally democratic solidarity in the Americas. polls predicted, Macri does not have the momentum Although Argentina’s $700 billion economy is ailing, it that a landslide victory would have produced, and the remains the second largest in South America; if Macri’s Peronist opposition may bounce back quickly to block proposed reforms restore growth, jobs, and solvency, significant reforms. A successful two-term mayor, he could blaze the trail for other countries whose econ- Macri will have his political skills tested as he rallies omies have been stunted by socialist policies. And if the public, the powerful provincial governors, and he follows through on his pledge to invoke Mercosur’s moderate Peronists to rescue the country’s economy. -

Esteban Iglesias Juan Bautista Lucca COMPILADORES La Argentina De Cambiemos La Argentina De Cambiemos / Esteban Actis

La Argentina de Cambiemos Esteban Iglesias Juan Bautista Lucca COMPILADORES La Argentina de Cambiemos La Argentina de Cambiemos / Esteban Actis... [et al.] ; compilado por Esteban Iglesias ; Juan Bautista Lucca. - 1a ed . - Rosario : UNR Editora. Editorial de la Universidad Nacional de Rosario, 2019. Libro digital, PDF Archivo Digital: descarga y online ISBN 978-987-702-344-2 1. Política. I. Actis, Esteban. II. Iglesias, Esteban, comp. III. Lucca, Juan Bautista, comp. CDD 320.82 UNR editora Editorial de la Universidad Nacional de Rosario Urquiza 2050 - S2000AOB / Rosario, República Argentina www.unreditora.unr.edu.ar / [email protected] Directora Editorial Nadia Amalevi Editor Nicolás Manzi Diagramación Eugenia Reboiro Foto de tapa y stenciles Juan Bautista Lucca Queda hecho el depósito que marca la ley 11.723 Ninguna parte de esta obra puede ser reproducida sin el permiso expreso del editor. Impreso en Argentina La Argentina de Cambiemos Esteban Iglesias Juan Bautista Lucca COMPILADORES Índice Introducción Juan Bautista Lucca y Esteban Iglesias 9 SECCIÓN I El Macrismo: cuando la honestidad reemplazó al patriotismo Gastón Souroujon 23 ¡Animémonos a imaginarlo! Análisis del discurso presidencial de Mauricio Macri Irene Lis Gindin 43 Cambiemos y las contradicciones de la democracia liberal José Gabriel Giavedoni 61 Cuando sube la marea feminista: resistencias y disputas de sentido en tiempos macristas Florencia Laura Rovetto 85 Gobernar CON y EN las redes en la Argentina de Cambiemos Sebastián Castro Rojas 103 SECCIÓN II Reminiscencias del radicalismo, del peronismo y retroproyecciones de un mundo nuevo en el gobierno de Cambiemos Juan Bautista Lucca 117 Mentime que me gusta: notas sobre Estado, Política y Administración en el Gobierno de Cambiemos Diego Julián Gantus 143 La Modernización de la Administración Pública Argentina 2015-2019. -

Documentazione Per L'attività Internazionale

XVII LEGISLATURA Documentazione per l’attività internazionale L’ATTIVITA‘ INTERNAZIONALE DELLA CAMERA DEI DEPUTATI NELLA XVI LEGISLATURA 15 marzo 2013 N. 3 Camera dei deputati XVII LEGISLATURA Documentazione per l’attività internazionale L’ATTIVITA‘ INTERNAZIONALE DELLA CAMERA DEI DEPUTATI NELLA XVI LEGISLATURA N. 3 A cura del Servizio Rapporti Internazionali Tel. 9515 E.mail [email protected] ________________________________________________________________ I dossier dei servizi e degli uffici della Camera sono destinati alle esigenze di documentazione interna per l’attività degli organi parlamentari e dei parlamentari. La Camera dei deputati declina ogni responsabilità per la loro eventuale utilizzazione o riproduzione per fini non consentiti dalla legge. I N D I C E Premessa .................................................................................................. Pag 1 Rapporti con i Parlamenti Paesi dell’Unione europea ............................................................. “ 5 Balcani............................................................................................ “ 81 Altri Paesi europei .......................................................................... “ 107 Federazione Russa, Caucaso e Paesi ex URSS ........................... “ 117 Mediterraneo e Medio Oriente........................................................ “ 139 Africa sub-sahariana ed australe.................................................... “ 177 Stati Uniti e Canada ...................................................................... -

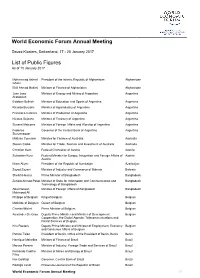

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Davos-Klosters, Switzerland, 17 - 20 January 2017 List of Public Figures As of 10 January 2017 Mohammad Ashraf President of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Afghanistan Ghani Eklil Ahmad Hakimi Minister of Finance of Afghanistan Afghanistan Juan Jose Minister of Energy and Mining of Argentina Argentina Aranguren Esteban Bullrich Minister of Education and Sports of Argentina Argentina Ricardo Buryaile Minister of Agroindustry of Argentina Argentina Francisco Cabrera Minister of Production of Argentina Argentina Nicolas Dujovne Minister of Treasury of Argentina Argentina Susana Malcorra Minister of Foreign Affairs and Worship of Argentina Argentina Federico Governor of the Central Bank of Argentina Argentina Sturzenegger Mathias Cormann Minister for Finance of Australia Australia Steven Ciobo Minister for Trade, Tourism and Investment of Australia Australia Christian Kern Federal Chancellor of Austria Austria Sebastian Kurz Federal Minister for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs of Austria Austria Ilham Aliyev President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Zayed Zayani Minister of Industry and Commerce of Bahrain Bahrain Sheikh Hasina Prime Minister of Bangladesh Bangladesh Zunaid Ahmed Palak Minister of State for Information and Communication and Bangladesh Technology of Bangladesh Abul Hassan Minister of Foreign Affairs of Bangladesh Bangladesh Mahmood Ali Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Belgium Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Charles Michel Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium -

Tapa En Pliego Aparte

TAPA EN PLIEGO APARTE Memoria y Balance General 2017 (Correspondiente al ejercicio cerrado el 31 de julio de 2017) Índice Autoridades y Convocatorias 7 Mensaje 23 Actividad Institucional 35 Gestión Operativa y Administrativa 79 Cámaras Arbitrales 109 Listado de Valores Negociables 117 Mercados Adheridos y Entidades del Sistema Bursátil 123 Responsabilidad Social y Compromiso con la Comunidad 143 Estados Contables 153 5 Autoridades Consejo Directivo ALBERTO A. PADOÁN Presidente RAÚL R. MEROI Vicepresidente Primero DANIEL A. NASINI Vicepresidente Segundo FERNANDO A. RIVERO Secretario ÁNGEL F. GIRARDI JORGE. R. TANONI Prosecretario Primero Prosecretario Segundo DANIEL N. GALLO Tesorero ÁNGEL A. TORTI LISANDRO J. ROSENTAL 9 Protesorero Primero Protesorero Segundo Vocales Titulares PABLO SCARAFONI JAVIER A. MARISCOTTI JUAN JOSÉ SEMINO IVANNA M. R. SANDOVAL Vocales Suplentes JOSÉ MARÍA JIMÉNEZ ALBERTO D. CURADO HUGO A. A. GRASSI Comisión Revisora de Cuentas Titulares Suplentes JOSÉ MARÍA CRISTIÁ (Presidente) JOSÉ C. TRÁPANI VICENTE LISTRO ENRIQUE M. LINGUA JORGE F. FELCARO Presidentes de las Cámaras Arbitrales que integran el Consejo Directivo FEDERICO G. HELMAN NÉSTOR O. BUSEGHIN Cámara Arbitral de Cereales Cámara Arbitral de Aceites Vegetales y Subproductos Presidentes de Entidades participantes que integran el Consejo Directivo ANDRÉS E. PONTE, ROFEX S.A PABLO A. BORTOLATO, Mercado Argentino de Valores S.A. FERNANDO L. BOTTA, Mercado Ganadero S.A. MARCELO J. ROSSI, Argentina Clearing S.A. ALEJANDRO SIMON, Aseguradores del Interior de la República Argentina PEDRO VIGNEAU, Asociación Argentina de Productores en Siembra Directa - A.A.P.R.E.S.I.D. RODOLFO L. ROSSI, Asociación de la Cadena de la Soja Argentina – ACSOJA ANÍBAL H.