Thailand and Cambodia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Temple Dispute

International Journal of East Asian Studies, 23(1) (2019), 58-83. Dynamic Roles and Perceptions: The Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Temple Dispute Ornthicha Duangratana1 1 Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand This article is part of the author’s doctoral dissertation, entitled “The Roles and Perceptions of the Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs through Governmental Politics in the Temple Dispute.” Corresponding Author: Ornthicha Duangratana, Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand E-mail: [email protected] Received: 11 Feb 19 Revised: 16 Apr 19 Accepted: 15 May 19 58 Abstract Thailand and Cambodia have long experienced swings between discordant and agreeable relations. Importantly, contemporary tensions between Thailand and Cambodia largely revolve around the disputed area surrounding the Preah Vihear Temple, or Phra Vi- harn Temple (in Thai). The dispute over the area flared after the independence of Cambodia. This situation resulted in the International Court of Justice adjudicating the dispute in 1962. Then, as proactive cooperation with regards to the Thai-Cambodian border were underway in the 2000s, the dispute erupted again and became salient between the years 2008 to 2013. This paper explores the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ (MFA) perceptions towards the overlapping border claim since the Cold War and concentrates on the changes in perceptions in the period from 2008 to 2013 when the Preah Vihear temple dispute rekindled. Moreover, to study their implications on the Thai-Cambodian relations, those perceptions are analyzed in connection to the roles of the MFA in the concurrent Thai foreign-policy apparatus. Under the aforementioned approach, the paper makes the case that the internation- al environment as well as the precedent organizational standpoint significantly compels the MFA’s perceptions. -

Mekong Cultural Diversity Beyond Borders

TABATA Yukitsugu, SATO Katsura (eds.) Mekong Cultural Diversity Beyond Borders Proceedings for the International Seminar & Symposium on Southeast Asian Cultural Heritage Studies Today March 2020 Institute for Cultural Heritage, Waseda University TABATA Yukitsugu, SATO Katsura (eds.) Mekong Cultural Diversity Beyond Borders Proceedings for the International Seminar & Symposium on Southeast Asian Cultural Heritage Studies Today March 2020 Institute for Cultural Heritage, Waseda University Notes The following are the proceedings of the International Seminar "Southeast Asian Cultural Heritage Studies Today" and Symposium "To Know and Share about Cultural Heritage" held on 23, 24 and 25 January, 2020, organized by the Institute for Cultural Heritage, Waseda University, as part of the project commissioned by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. Each paper of the Seminar was prepared by the presenter. The record of the Symposium was edited based on the presentation materials and audio recordings. 例 言 本報告書は、2020 年 1 月 23 日、24 日、25 日に文化庁委託事業として早稲田大学文化財総合調査研究所が開催した 国際研究会「東南アジア文化遺産研究の現在」及びシンポジウム「文化遺産を知り、そして伝える」の内容を収録した ものである。研究会の論考は各発表者により書き下ろされた。シンポジウムについては発表資料及び録音記録に基づい て編集した。 Mekong Cultural Diversity Beyond Borders Proceedings for the International Seminar & Symposium on Southeast Asian Cultural Heritage Studies Today March 2020 Published by Institute for Cultural Heritage, Waseda University Toyama 1-24-1, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-8644, Japan TEL & FAX +81-(0)3-5286-3647 Edited by TABATA Yukitsugu, SATO Katsura © Agency for Cultural Affairs & Institute for Cultural Heritage, Waseda University All rights reserved. Table of Contents Part I Seminar on Southeast Asian Cultural Heritage Studies Today [Opening Remarks] What is the Creativity of the World Heritage Cities in Mekong Basin Countries ? ...... 1 NAKAGAWA Takeshi 1. -

(Unofficial Translation) Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation Due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) No

(Unofficial Translation) Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) No. 1/2564 Re : COVID-19 Zoning Areas Categorised as Maximum COVID-19 Control Zones based on Regulations Issued under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations B.E. 2548 (2005) ------------------------------------ Pursuant to the Declaration of an Emergency Situation in all areas of the Kingdom of Thailand as from 26 March B.E. 2563 (2020) and the subsequent 8th extension of the duration of the enforcement of the Declaration of an Emergency Situation until 15 January B.E. 2564 (2021); In order to efficiently manage and prepare the prevention of a new wave of outbreak of the communicable disease Coronavirus 2019 in accordance with guidelines for the COVID-19 zoning based on Regulations issued under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations B.E. 2548 (2005), by virtue of Clause 4 (2) of the Order of the Prime Minister No. 4/2563 on the Appointment of Supervisors, Chief Officials and Competent Officials Responsible for Remedying the Emergency Situation, issued on 25 March B.E. 2563 (2020), and its amendments, the Prime Minister, in the capacity of the Director of the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration, with the advice of the Emergency Operation Center for Medical and Public Health Issues and the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration of the Ministry of Interior, hereby orders Chief Officials responsible for remedying the emergency situation and competent officials to carry out functions in accordance with the measures under the Regulations, for the COVID-19 zoning areas categorised as maximum control zones according to the list of Provinces attached to this Order. -

The Provincial Business Environment Scorecard in Cambodia

The Provincial Business Environment Scorecard in Cambodia A Measure of Economic Governance and Regulatory Policy November 2009 PBES 2009 | 1 The Provincial Business Environment Scorecard1 in Cambodia A Measure of Economic Governance and Regulatory Policy November 2009 1 The Provincial Business Environment Scorecard (PBES) is a partnership between the International Finance Corporation and the donors of the MPDF Trust Fund (the European Union, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Switzerland), and The Asia Foundation, with funding support from Danida, DFID and NZAID, the Multi-Donor Livelihoods Facility. PBES 2009 | 3 PBES 2009 | 4 Table of Contents List of Tables ..........................................................................................................................................................iii List of Figures .........................................................................................................................................................iv Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................................v Acknowledgments .....................................................................................................................................................vi 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1. PBES Scorecard and Sub-indices .......................................................................................... -

Thailand's Moment of Truth — Royal Succession After the King Passes Away.” - U.S

THAILAND’S MOMENT OF TRUTH A SECRET HISTORY OF 21ST CENTURY SIAM #THAISTORY | VERSION 1.0 | 241011 ANDREW MACGREGOR MARSHALL MAIL | TWITTER | BLOG | FACEBOOK | GOOGLE+ This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This story is dedicated to the people of Thailand and to the memory of my colleague Hiroyuki Muramoto, killed in Bangkok on April 10, 2010. Many people provided wonderful support and inspiration as I wrote it. In particular I would like to thank three whose faith and love made all the difference: my father and mother, and the brave girl who got banned from Burma. ABOUT ME I’m a freelance journalist based in Asia and writing mainly about Asian politics, human rights, political risk and media ethics. For 17 years I worked for Reuters, including long spells as correspondent in Jakarta in 1998-2000, deputy bureau chief in Bangkok in 2000-2002, Baghdad bureau chief in 2003-2005, and managing editor for the Middle East in 2006-2008. In 2008 I moved to Singapore as chief correspondent for political risk, and in late 2010 I became deputy editor for emerging and frontier Asia. I resigned in June 2011, over this story. I’ve reported from more than three dozen countries, on every continent except South America. I’ve covered conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Lebanon, the Palestinian Territories and East Timor; and political upheaval in Israel, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand and Burma. Of all the leading world figures I’ve interviewed, the three I most enjoyed talking to were Aung San Suu Kyi, Xanana Gusmao, and the Dalai Lama. -

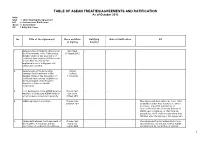

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Preah Vihear Province Investment Information

Municipality and Province Preah Vihear Province Investment Information Preah Vihear Province Preah Vihear Road Network 99 Municipality and Province Preah Vihear Province Investment Information I. Introduction to the Province Preah Vihear is located in northern Cambodia, 294 km from Phnom Penh running through National Road No. 6 and 629. The province borders Stung Treng province to the east, Siem Reap province and Oddar Meanchey province to the west, Thailand and Laos to the north and Kampong Thom province to the south. While much of the province is extremely remote and strongly forested, and the province is one of least populated in Cambodia, it is home to three impressive legacies from the Angkorian era: the mountain temple of Prasat Preah Vihear, which is well known as a World Heritage Site, the 10th-century capital of Koh Ker and the mighty Preak Khan. These legacies attract many local and international tourists every year. The provincial economy 85% based on farming and the remaining 15% based on fishing and other sectors. Recently, because of its border with Thailand, international trade has increased slightly, becoming another important sector for the province's economy. The province is endowed with endless natural treasures. With acres of dense, hilly forests and scrub green vegetation, Preah Vihear is indeed an ideal getaway destination to Cambodia’s nature with the breathtaking views over the Dangkrek Mountains and lush jungle from Preah Vihear temples. Preah Vihear has abundant water resources from 219 natural water reservoirs -

Kingdom of Cambodia the Temple of Preah Vihear Inscribed on the World Heritage List (Unesco) Since 2008

KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA THE TEMPLE OF PREAH VIHEAR INSCRIBED ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST (UNESCO) SINCE 2008 Edited by the Office of the Council of Ministers PHNOM PENH MAY 2010 ON THE SUCCESSFUL INSCRIPTION OF THE TEMPLE OF PREAH VIHEAR ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST (07 July 2008, Quebec, Canada during the 32nd session of the World Heritage Committee) “This is a new sense of pride for the people of our Kingdom, as well as for all the people in the region and the world that the Temple of Preah Vihear was recognized by ICOMOS as an outstanding masterpiece of Khmer architecture with an outstanding universal value, and was inscribed on the World Heritage List.” “The inscription of the Temple of Preah Vihear requires the international community as a whole to protect and preserve this world heritage for the benefits of future gen- erations.” Samdech Akka Moha Sena Padei Techo HUN SEN Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Cambodia, 08 July 2008 “In fact, the Decision of the 31st session of the World Heritage Committee in Christchurch, New Zealand, July 2007 contains 3 conditions. First, it is essential that Cambodia strengthens the conservation of the Temple; second, Cambodia must develop an appropriate management plan and submit it to the World Heritage Centre by 01 February 2008, because the review process would take up many months until July, to see whether or not our management plan is appropriate; and third, Cambodia and Thailand should develop a close cooperation in support of the inscription. If Cambodia fulfills these three conditions, then in 2008 the inscription will be automatic. -

The Thai-Lao Border Conflict

ERG-IO NOT FOR PUBLICATION WITHOUT WRITER'S CONSENT INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS 159/1 Sol Mahadlekluang 2 Raj adamri Road Bangkok February 3, 1988 Siblinq Rivalry- The Thai-Lao Border Conflict Mr. Peter Mart in Institute of Current World Affairs 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover, NH 03755 Dear Peter, The Thai Army six-by-six truck strained up the steep, dirt road toward Rom Klao village, the scene of sporadic fighting between Thai and Lao troops. Two days before, Lao "sappers" had ambushed Thai soldiers nearby, killing II. So, as the truck crept forward with the driver gunning the engine to keep it from stalling, I was glad that at least this back road to the disputed mountaintop was safe. For the past three months, reports of Thai and Lao soldiers battling to control this remote border area have filled the headlines of the local newspapers. After a brief lull, the conflict has intensified following the Lao ambush on January 20. The Thai Army says that it will now take "decisive action" to drive the last Lao intruders from the Rom Klao area, 27 square miles of land located some 300 miles northeast of Bangkok. When Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda visited the disputed tract, the former cavalry officer dramatically staked out Thai territory by posing in combat fatigues, cradling a captured Lao submachine gun. Last week, the Thai Foreign Ministry escorted some 40 foreign diplomats to the region to butress the Thai claim, but had to escort them out again when a few Lao artillery shells fell nearby. -

Board of Editors

2020-2021 Board of Editors EXECUTIVE BOARD Editor-in-Chief KATHERINE LEE Managing Editor Associate Editor KATHRYN URBAN KYLE SALLEE Communications Director Operations Director MONICA MIDDLETON CAMILLE RYBACKI KOCH MATTHEW SANSONE STAFF Editors PRATEET ASHAR WENDY ATIENO KEYA BARTOLOMEO Fellows TREVOR BURTON SABRINA CAMMISA PHILIP DOLITSKY DENTON COHEN ANNA LOUGHRAN SEAMUS LOVE IRENE OGBO SHANNON SHORT PETER WHITENECK FACULTY ADVISOR PROFESSOR NANCY SACHS Thailand-Cambodia Border Conflict: Sacred Sites and Political Fights Ihechiluru Ezuruonye Introduction “I am not the enemy of the Thai people. But the [Thai] Prime Minister and the Foreign Minister look down on Cambodia extremely” He added: “Cambodia will have no happiness as long as this group [PAD] is in power.” - Cambodian PM Hun Sen Both sides of the border were digging in their heels; neither leader wanted to lose face as doing so could have led to a dip in political support at home.i Two of the most common drivers of interstate conflict are territorial disputes and the politicization of deep-seated ideological ideals such as religion. Both sources of tension have contributed to the emergence of bloody conflicts throughout history and across different regions of the world. Therefore, it stands to reason, that when a specific geographic area is bestowed religious significance, then conflict is particularly likely. This case study details the territorial dispute between Thailand and Cambodia over Prasat (meaning ‘temple’ in Khmer) Preah Vihear or Preah Vihear Temple, located on the border between the two countries. The case of the Preah Vihear Temple conflict offers broader lessons on the social forces that make religiously significant territorial disputes so prescient and how national governments use such conflicts to further their own political agendas. -

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development. -

A Coup Ordained? Thailand's Prospects for Stability

A Coup Ordained? Thailand’s Prospects for Stability Asia Report N°263 | 3 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Thailand in Turmoil ......................................................................................................... 2 A. Power and Legitimacy ................................................................................................ 2 B. Contours of Conflict ................................................................................................... 4 C. Troubled State ............................................................................................................ 6 III. Path to the Coup ............................................................................................................... 9 A. Revival of Anti-Thaksin Coalition ............................................................................. 9 B. Engineering a Political Vacuum ................................................................................ 12 IV. Military in Control ............................................................................................................ 16 A. Seizing Power