Older Population and Health System: a Profile of Thailand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

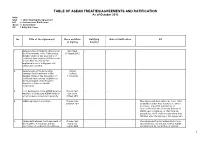

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Tau Tae Tching Or Lao-Tse (The Right Path)

TAl CULTURE Vol. 20 Tai peoples in ChinaChina.. Part III _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Oliver Raendchen * TAI ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY: tau tae tching or lao-tse (The Right Path) Abstract In this essay, ancient Tai philosophy (way of life; perception of the world) is approached in a specific way. Following more than 20 years of his comparative and interdisciplinary study in the ancient philosophy expressed in the tau tae tching text on the one hand and the world view, way of life and practical behavior of the Tai peoples on the other hand, the author has been developing the firm belief that the ancient philosophical text tau tae tching - which is found in old written exemplars in the Chinese language and attributed to Laotse - is most probably rooted in the ancient traditions and philosophy of the Tai peoples whose forefathers settled in historical times in what is today South China. In the opinion of the author, the written philosophical text tau tae tching was created as a mirror, as a secondary image, of an existing culture, namely, the world view, way of life, and practical rules of behavior of the Tai peoples. Compared to the concrete behavioural rules, traditional laws, etc., of the Tai peoples, the tau tae tching is a philosophical condensation and abstraction. It is something like a bible of behavioural norms and was used not only for worshipping the holy “right path” of behaviour, but in fact represents a complete value system which reinforced the social order. As such, it was also the source for intellectuals to compete with other value systems (e.g., that of Confucius) which was followed by other ethnic groups, namely the Han-Chinese. -

The Ethnography of Tai Yai in Yunnan

LAK CHANG A reconstruction of Tai identity in Daikong LAK CHANG A reconstruction of Tai identity in Daikong Yos Santasombat Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Cover: The bride (right) dressed for the first time as a married woman. Previously published by Pandanus Books National Library in Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Santasombat, Yos. Lak Chang : a reconstruction of Tai identity in Daikong. Author: Yos Santasombat. Title: Lak chang : a reconstruction of Tai identity in Daikong / Yos Santasombat. ISBN: 9781921536380 (pbk.) 9781921536397 (pdf) Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Tai (Southeast Asian people)--China--Yunnan Province. Other Authors/Contributors: Thai-Yunnan Project. Dewey Number: 306.089959105135 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. First edition © 2001 Pandanus Books This edition © 2008 ANU E Press iv For my father CONTENTS Preface ix Acknowledgements xii Introduction 1 Historical Studies of the Tai Yai: A Brief Sketch 3 The Ethnography of Tai Yai in Yunnan 8 Ethnic Identity and the Construction of an Imagined Tai Community 12 Scope and Purpose of this Study 16 Chapter One: The Setting 19 Daikong and the Chinese Revolution 20 Land Reform 22 Tai Peasants and Cooperative Farming 23 The Commune 27 Daikong and the Cultural Revolution 31 Lak -

The Role in Politics of Malaysian of Thai Race

The 2016 WEI International Academic Conference Proceedings Rome, Italy THE ROLE IN POLITICS OF MALAYSIAN OF THAI RACE Rawikarn Amnuay Phranakhon Rajabhat University, Bangkok, Thailand Abstract The research topic of "The Role in Politics of Malaysian of Thai Race" is a part of a research project on Comparison of Structural Pattern and the People's Involvement in Local Administration in Thailand and Malaysia. The research is aimed to study the role in politics of the Malaysian of Thai race. This research is a qualitative research based on a review of documents from both inside the country and abroad as well as interviews of important sources of information to include the President of the Thai Malaysian Association, leaders of Thai Malaysian communities, and the Malaysian people. The derived information was then analyzed using inductive method, logical analysis, and descriptive narration. The research found that Malaysian of Thai race as Malaysian and Thai citizen have very little role in politics both in national level and local administration or even civil politics. The people of Thai race are in status of voters or supporters of their favorite political parties only due to their viewpoint of politics and administration as the leader's business and not their own. They do not give precedence to grouping together to carry out political activities. Meanwhile, the discoveries of factors that affect on the Malaysian of Thai race's political roles show that these people pay more attention to religion and culture which they see related to merit and demerit. Economically, Malaysian of Thai race mostly have agricultural profession; so most of them are in the lower middle class who cannot pay more attention to politics than making a living. -

Tsunami Relief and Reconstruction: Through the Eyes of the Children

6-Month Progress Report Tsunami Relief and Reconstruction Through the Eyes of the Children J. Carrier From the Chair To our contributors, colleagues and friends: In the coming months and years, our work will continue in full force to protect and rebuild the lives of children and their The devastating effects of the December 26 earthquake and families, and help them recover their physical and emotional tsunami were historic in magnitude, and our response is the health and well-being. This is no small task - many teachers, largest in Save the Children's 85-year history. Families lost their schools, parents, homes, health facilities, health professionals homes and livelihoods. Whole communities were destroyed. and jobs were lost in this disaster. The millions that survived, particularly children, were left vulnerable to disease, starvation and potential exploitation The generosity of the global public through the Save the and abuse. Children family has been unprecedented, with contributions in excess of $245 million to fund the emergency response and the Save the Children, active in many of the worst-affected regions comprehensive five-year plan for children highlighted in this for 30 years or more, moved immediately to deliver life-saving report. relief to more than 625,000 individuals, including 250,000 children, providing shelter, food, clean water and access to You can take pride in what has been accomplished for children medical care. This rapid response helped avert a second wave in the first phase of this emergency, and draw inspiration from Cover photo: David Crump/Daily Mail of death from malnutrition and disease that many experts the continued expansion of our efforts, from our heroic staff This page: Michael Bisceglie Through the Eyes of the Children anticipated would follow the disaster. -

The Thai-Lao Border Conflict

ERG-IO NOT FOR PUBLICATION WITHOUT WRITER'S CONSENT INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS 159/1 Sol Mahadlekluang 2 Raj adamri Road Bangkok February 3, 1988 Siblinq Rivalry- The Thai-Lao Border Conflict Mr. Peter Mart in Institute of Current World Affairs 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover, NH 03755 Dear Peter, The Thai Army six-by-six truck strained up the steep, dirt road toward Rom Klao village, the scene of sporadic fighting between Thai and Lao troops. Two days before, Lao "sappers" had ambushed Thai soldiers nearby, killing II. So, as the truck crept forward with the driver gunning the engine to keep it from stalling, I was glad that at least this back road to the disputed mountaintop was safe. For the past three months, reports of Thai and Lao soldiers battling to control this remote border area have filled the headlines of the local newspapers. After a brief lull, the conflict has intensified following the Lao ambush on January 20. The Thai Army says that it will now take "decisive action" to drive the last Lao intruders from the Rom Klao area, 27 square miles of land located some 300 miles northeast of Bangkok. When Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda visited the disputed tract, the former cavalry officer dramatically staked out Thai territory by posing in combat fatigues, cradling a captured Lao submachine gun. Last week, the Thai Foreign Ministry escorted some 40 foreign diplomats to the region to butress the Thai claim, but had to escort them out again when a few Lao artillery shells fell nearby. -

Curriculum Vitae Stanley Mays Arua

CURRICULUM VITAE STANLEY MAYS ARUA Personal Details SURNAME : ARUA GIVEN NAMES : STANLEY MAYS BIRTH DATE : 29th June 1972 HOME DISTRICT/PROV : Bereina, Central Province, PNG MARITAL STATUS : Married with 8 children RESIDENTIAL ADDRESS : S239 L24: Gerehu Stg 2. NCD. CONTACT PHONE : 3019233: Email: : [email protected] Current Status: Coordinator – Program Compliance Development Partner Compliance & Coordination Unit Department of Prime Minister & NEC Academic Qualifications Post Graduate Diploma of Arts in Political Science and International Relations – Research -, Auckland University, NZ, 1999 Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and International Relations, University of PNG, 1998 Matriculation in Social Science – Education Faculty, University of PNG, 1995 Grade 10 Certificate, De La Salle Bomana, National Capital District, Department of Education, 1988 Special Training Professional Program for Diplomats from Pacific Island Countries, Ministry of Commerce (Certificate June 2011) People’s Republic of China. International Program on Public Administration and Good Governance, KOICA (Certificate November 2008) Republic of Korea Foreign Service Training, PNGDFAT/NZMFAT (Certificate July 2008) Port Moresby, PNG Time Management and Delegation, PNG Bankers’ College (Certificate 2002) Port Moresby, PNG 1 Positive Work Attitudes, Dept. Labour and Industrial Relations, (Certificate 2001) PNG Public Service, Port Moresby Small Business Management, Ausbiz Limited (Certificate 1999) AusAid Secretary to the University of the South Pacific -

Fact Sheet – Thailand Official Name Kingdom of Thailand Capital Bangkok

Fact Sheet – Thailand Official Name Kingdom of Thailand Capital Bangkok (population 10 million) Area 513,115 sq km (about 1/6th of area of India) Provinces 77 provinces including one Specially Governed District (Bangkok) Major cities Bangkok, Chiang Mai, Phuket, Khon Kaen, Nakorn Ratchasima, Ubon Ratchathanee, Hat Yai and Udon Thani Population 67.09 million (July 2012) population growth rate – 0.7% per annum Religion Buddhist 95%, Muslims 3.8%, Christians 0.5%, others 1.7%. Ethnic Groups Thais, Chinese, Malays, the Burmese, Lao, Khmers Currency Baht (1 US$ - 29.45 Baht - May 2013) National Day 5 December (Birthday of HM King Bhumibol Adulyadej) Languages Thai, Chinese, English Climate Tropical: temperatures vary between 19 C to 38 C Government Constitutional Monarchy with Parliamentary Democracy Head of State HM Bhumibol Adulyadej, the 9thking (Rama IX) of the House of Chakri, is the world's longest-serving ruler (since 1946). The king is titled as the upholder of the Buddhist religion & the defender of all faiths. Crown Prince is HRH Mahavajiralongkorn. Head of PM Yingluck Shinawatra (since August 2011), Thailand’s first female Government PM and the 28th PM of Thailand, member of the Pheu Thai Party Parliament The National Assembly of Thailand is a bicameral body. The Senate (National (Upper House) is a non-partisan legislative chamber, composed of 150 Assembly) members (76 Senators are directly elected from the Provinces, while 74 are appointed from various sectors by the Senate Selection Committee). The Senate operates under fixed terms of 6 years. The House of Representatives (Lower House) with a 4 years term has a total 500 Members (375 Members are elected through single constituency elections, while the other 125 are appointed on the basis of percentage of votes obtained by each party. -

Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty

The Asian Development Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development do not guarantee the accuracy of this document and accept no responsibility whatsoever for any consequences of its use. This document was obtained in September 2007. Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 2 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 3 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 4 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 5 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 6 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 7 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 8 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 -

Double Identity Representation of Chinese Shrines in Muang Phuket District

i Double Identity Representation of Chinese Shrines in Muang Phuket District Panuwat Chanasakun A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Chinese Studies Prince of Songkla University 2017 Copyright of Prince of Songkla University ii Thesis Title Double Identity Representation of Chinese Shrines in Muang Phuket District Author Mr. Panuwat Chanasakun Major Program Chinese Studies Major Advisor Examining Committee: ……………………………………………… ….…………….………………………….Chairperson (Dr Pim De Jong) (Dr. Yupin Karanyadech) .……………….…………………….……Committee (Dr. Chawarote Valyamedhi) ……………….…………………….……Committee (Dr Pim De Jong) The Graduate School, Prince of Songkla University, has approved this thesis as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Chinese studies. ………….……….………………………………………… (Assoc. Prof. Dr. Teerapol Srichana) Dean of Graduate School iii This is to certify that the work here submitted is the result of the candidate’s own investigations. Due acknowledgement has been made of any assistance received. ........................................................Signature (Dr. Pim de Jong) Major Advisor ........................................................Signature (Mister Panuwat Chanasakun) Candidate iv I hereby certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not being currently submitted in candidature for any degree. ...............................................................Signature (Mister Panuwat Chanasakun) Candidate v Thesis Title Double Identity Representation of Chinese Shrines in Muang Phuket District Author Mister Panuwat Chanasakun Major Program Chinese Studies Academic Year 2016 ABSTRACT “Double Identity Representation of Chinese Shrine in Phuket District” has the main objectives o study the adaptations of Chinese culture in the context of Thai society through Chinese shrine in Muang Phuket District and to comprehend the phenomena of double identity which represent through Chinese shrine in Muang Phuket District. -

Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement Between Thailand and Indonesia

Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement between Thailand and Indonesia Completed in 2000 This document was downloaded from ASEAN Briefing (www.aseanbriefing.com) and was compiled by the tax experts at Dezan Shira & Associates (www.dezshira.com). Dezan Shira & Associates is a specialist foreign direct investment practice, providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in emerging Asia. AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE KINGDOM OF THAILAND AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME The Government of the Kingdom of Thailand and the Government of the Republic of Indonesia, DESIRING to conclude an Agreement for the avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion with respect to taxes on income, HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS : Article 1 PERSONAL SCOPE This Agreement shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States. 2 Article 2 TAXES COVERED 1. This Agreement shall apply to taxes on income imposed on behalf of one of the Contracting States, irrespective of the manner in which they are levied. 2. There shall be regarded as taxes on income all taxes imposed on total income or on elements of income, including taxes on gains from the alienation of movable or immovable property, taxes on the total amounts of wages or salaries paid by enterprises, as well as taxes on capital appreciation. 3. The existing taxes to which the Agreement shall apply are: (a) in Thailand : (i) the Income Tax; (ii) the Petroleum income Tax. -

3 History of Thailand in Brief in Order to Understand the Culture of a State, It Is Necessary to Trace Back Different Eras of the History of That State

3 History of Thailand in Brief In order to understand the culture of a state, it is necessary to trace back different eras of the history of that state. The history of Thailand begins 5,000 years ago; the ancestors of today’s Thai people lived in southern China areas. Through various migration streams they worked their way south to Thailand, Burma and Laos. They entered the Southeast Asian peninsular, today’s Thailand at Chiang Saen, on the southern banks of Mekong River. It was the migrants from southern China who formed the first city states in the northern regions of present day Thailand.32 3.1 The Origin of Thai People and Historical Development According to Noppawan Sirivejkul33 the Thai historical development may be divided into 9 eras which can be briefly summarized as follows: Table 15: Division of Thai Historical Eras Era or Kingdom Century A.D. Important Development 1. Funan Kingdom 1st – 6th 43 B.C.- 557 A.D. Mekong Basin Settlement 2. Dvaravati Kingdom 6th – 11th 557 - 1057 Influence of Indian Culture 3. Lawo (Lopburi) 10th – 12th 957 - 1157 Era of Disputes 4. Haripunchai (Lamphun) 7th - 13th 657 - 1292 Religious Development Era 5. Lanna Kingdom 13th – 16th 1296 - 1355 Kingdom Establishment Age 1355 – 1525 Golden Age of Lanna 1525 - 1558 Lanna Age of Decline 6. Sukhothai Kingdom 12th - 15th 1157 - 1438 Pottery, Celadon Age 7. Ayutthaya Kingdom 14th – 18th 1350 - 1767 417 years of Prosperity 8. Thonburi 18th 1767 - 1782 15 years of Reconstruction 9. Rattanakosin (Bangkok) 18th - Present 1782 - 1851 Chakri Dynasty Era 1851 – 1932 Political Reform 1932 - Present Democratic Ruling Source: Noppawan Sirivejkul.