Comparing Regime Continuity and Change: Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smuggling Cultures in the Indonesia-Singapore Borderlands

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Amsterdam University Press as: Ford, M., Lyons, L. (2012). Smuggling Cultures in the Indonesia-Singapore Borderlands. In Barak Kalir and Malini Sur (Eds.), Transnational Flows and Permissive Polities: Ethnographies of Human Mobilities in Asia, (pp. 91-108). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. Smuggling Cultures in the Indonesia-Singapore Borderlands Michele Ford and Lenore Lyons The smuggling will never stop. As long as seawater is still seawater and as long as the sea still has water in it, smuggling will continue in the Riau Islands. Tengku Umar, owner of an import-export business Borders are lucrative zones of exchange and trade, much of it clandestine. Smuggling, by definition, 'depends on the presence of a border, and on what the state declares can be legally imported or exported' (Donnan & Wilson 1999: 101), and while free trade zones and growth triangles welcome the free movement of goods and services, border regions can also become heightened areas of state control that provide an environment in which smuggling thrives. Donnan and Wilson (1999: 88) argue that acts of smuggling are a form of subversion or resistance to the existence of the border, and therefore the state. However, there is not always a conflict of interest and struggle between state authorities and smugglers (Megoran, Raballand, & Bouyjou 2005). Synergies between the formal and informal economies ensure that illegal cross-border trade does not operate independently of systems of formal regulatory authority. -

Civilian Control Over the Military in East Asia

Civilian Control over the Military in East Asia Aurel Croissant Ruprecht-Karls-Universität, Heidelberg September 2011 EAI Fellows Program Working Paper Series No. 31 Knowledge-Net for a Better World The East Asia Institute(EAI) is a nonprofit and independent research organization in Korea, founded in May 2002. The EAI strives to transform East Asia into a society of nations based on liberal democracy, market economy, open society, and peace. The EAI takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the Korean government. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in its publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors. is a registered trademark. © Copyright 2011 EAI This electronic publication of EAI intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Copies may not be duplicated for commercial purposes. Unauthorized posting of EAI documents to a non-EAI website is prohibited. EAI documents are protected under copyright law. The East Asia Institute 909 Sampoong B/D, 310-68 Euljiro 4-ga Jung-gu, Seoul 100-786 Republic of Korea Tel. 82 2 2277 1683 Fax 82 2 2277 1684 EAI Fellows Program Working Paper No. 31 Civilian Control over the Military in East Asia1 Aurel Croissant Ruprecht-Karls-Universität, Heidelberg September 2011 Abstract In recent decades, several nations in East Asia have transitioned from authoritarian rule to democracy. The emerging democracies in the region, however, do not converge on a single pattern of civil-military relations as the analysis of failed institutionalization of civilian control in Thailand, the prolonged crisis of civil– military relations in the Philippines, the conditional subordination of the military under civilian authority in Indonesia and the emergence of civilian supremacy in South Korea in this article demonstrates. -

Observations on the State of Indigenous Human Rights in Papua New Guinea Prepared for United Nations Human Rights Council

Observations on the State of Indigenous Human Rights in Papua New Guinea Prepared for United Nations Human Rights Council: March 2020 3rd Cycle of Universal Periodic Review of Papua New Guinea 39th Session of the Human Rights Council Cultural Survival is an international Indigenous rights organization with a global Indigenous leadership and consultative status with ECOSOC. Cultural Survival is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in the United States. Cultural Survival monitors the protection of Indigenous Peoples' rights in countries throughout the world and publishes its findings in its magazine, the Cultural Survival Quarterly, and on its website: www.cs.org. Cultural Survival, 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Tel: 1 (617) 441-5400 | [email protected] AMERICAN INDIAN LAW CLINIC OF THE UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO Established in 1992, the Clinic is one of the first of its kind, representing individuals, Indian Tribes and Tribal entities in a variety of settings involving federal Indian law, as well as the laws and legal systems of Indian Country. It also works with the United Nations in representing Indigenous rights. https://www.colorado.edu/law/academics/clinics/american-indian-law-clinic American Indian Law Clinic 404 UCB Boulder, CO 80309 USA Tel: 1 (303) 492-7079 | [email protected] 1 I. Executive Summary Despite recommendations in the first and second cycle aimed at improving the conditions and self-determination of Indigenous Peoples in Papua New Guinea, the government has failed to adequately address rights violations, including inadequate access to basic services such as healthcare. -

Initiating Bus Rapid Transit in Jakarta, Indonesia

Initiating Bus Rapid Transit in Jakarta, Indonesia John P. Ernst On February 1, 2004, a 12.9-km (8-mi) bus rapid transit (BRT) line began the more developed nations, the cities involved there frequently lack revenue operation in Jakarta, Indonesia. The BRT line has incorporated three critical characteristics more common to cities in developing most of the characteristics of BRT systems. The line was implemented in countries: only 9 months at a cost of less than US$1 million/km ($1.6 million/mi). Two additional lines are scheduled to begin operation in 2005 and triple 1. High population densities, the size of the BRT. While design shortcomings for the road surface and 2. Significant existing modal share of bus public transportation, terminals have impaired performance of the system, public reaction has and been positive. Travel time over the whole corridor has been reduced by 3. Financial constraints providing a strong political impetus to 59 min at peak hour. Average ridership is about 49,000/day at a flat fare reduce, eliminate, or prevent continuous subsidies for public transit of 30 cents. Furthermore, 20% of BRT riders have switched from private operation. motorized modes, and private bus operators have been supportive of expanding Jakarta’s BRT. Immediate improvements are needed in the These three characteristics combine to favor the development of areas of fiscal handling of revenues and reconfiguring of other bus routes. financially self-sustaining BRT systems that can operate without gov- The TransJakarta BRT is reducing transport emissions for Jakarta and ernment subsidy after initial government expenditures to reallocate providing an alternative to congested streets. -

Malaysia, September 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Malaysia, September 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: MALAYSIA September 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Malaysia. Short Form: Malaysia. Term for Citizen(s): Malaysian(s). Capital: Since 1999 Putrajaya (25 kilometers south of Kuala Lumpur) Click to Enlarge Image has been the administrative capital and seat of government. Parliament still meets in Kuala Lumpur, but most ministries are located in Putrajaya. Major Cities: Kuala Lumpur is the only city with a population greater than 1 million persons (1,305,792 according to the most recent census in 2000). Other major cities include Johor Bahru (642,944), Ipoh (536,832), and Klang (626,699). Independence: Peninsular Malaysia attained independence as the Federation of Malaya on August 31, 1957. Later, two states on the island of Borneo—Sabah and Sarawak—joined the federation to form Malaysia on September 16, 1963. Public Holidays: Many public holidays are observed only in particular states, and the dates of Hindu and Islamic holidays vary because they are based on lunar calendars. The following holidays are observed nationwide: Hari Raya Haji (Feast of the Sacrifice, movable date); Chinese New Year (movable set of three days in January and February); Muharram (Islamic New Year, movable date); Mouloud (Prophet Muhammad’s Birthday, movable date); Labour Day (May 1); Vesak Day (movable date in May); Official Birthday of His Majesty the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (June 5); National Day (August 31); Deepavali (Diwali, movable set of five days in October and November); Hari Raya Puasa (end of Ramadan, movable date); and Christmas Day (December 25). Flag: Fourteen alternating red and white horizontal stripes of equal width, representing equal membership in the Federation of Malaysia, which is composed of 13 states and the federal government. -

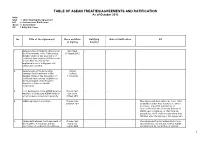

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Tax Alert the New Tax Treaty Between Singapore and Indonesia

Tax Alert ISSUE 03 | MARCH 2020 The New Tax Treaty between Singapore and Indonesia: Capital Gains Protection included at last! On 4 February 2020, Singapore and Indonesia dividend and interest income, which remain 10% signed an updated Avoidance of Double Taxation to15% for dividends and 10% for interest. It is Agreement (treaty). The new treaty will enter somewhat disappointing that there was no into force after it has been ratified by both reduction in the dividend WHT rate of 10% for countries, with the earliest possible date of substantial shareholdings to match the Hong effect being 1 January 2021 if ratified by both Kong – Indonesia tax treaty. Nevertheless, there countries during the course of the year 2020. are some positive changes which are set out Many of the existing treaty provisions continue, below. including the withholding tax (WHT) rates on 1. Introduction of a Capital Gains Article – impose up to 10% WHT on such income, as on any Including Protection from Indonesian Tax on other interest income. Sales of Indonesian Shares and Bonds While this will not affect Indonesian Government The existing treaty doesn’t have a capital gains article bonds that are issued offshore, as these already and hence does not restrict Indonesia’s ability to enjoy an exemption from interest WHT under impose taxes on Singaporean sellers of Indonesian Indonesian domestic law, it will impact Indonesian assets, including shares and bonds. This has long Government bonds that are issued in Indonesia; been a disadvantage of the Singapore – Indonesia tax hence, Singapore investors should take note of the treaty when compared to other Indonesian tax potential for increased interest WHT on their treaties, particularly as Indonesian domestic law Indonesian bond investments when the new treaty imposes a 5% WHT on gross proceeds for the sale of takes effect. -

399 International Court of Justice Case Between Indonesia And

International Court of Justice Case between Indonesia and Malaysia Concerning Sovereignty over Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan Introduction On 2 November 1998 Indonesia and Malaysia jointly seised the International Court of Justice (ICJ) of their dispute concerning sovereignty over the islands of Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan in the Celebes Sea.' They did so by notifying the Court of a Special Agreement between the two states, signed in Kuala Lumpur on 31 May 1997 and which entered into force on 14 May 1998 upon the exchange of ratifying instruments. In the Special Agreement, the two parties request the Court "to determine on the basis of the treaties, agreements and other evidence furnished by [the two parties], whether sovereignty over Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan belongs to the Republic of Indonesia or Malaysia". The parties expressed the wish to settle their dispute "in the spirit of friendly relations existing between [them] as enunciated in the 1976 Treaty of Amity and Co-operation in Southeast Asia" and declared in advance that they will "accept the Judgement of the Court given pursuant to [the] Special Agreement as final and binding upon them." On 10 November 1998 the ICJ made an Order' fixing the time limits for the respective initial pleadings in the case as follows: 2 November 1999 for the filing by each of the parties of a Memorial; and 2 March 2000 for the filing of the counter-memorials. By this order the Court also reserved subsequent procedure on this case for future decision. In fixing the time limits for the initial written pleadings, the Court took account and applied the wishes expressed by the two parties in Article 3, paragraph 2 of their Special Agreement wherein they provided that the written pleadings should consist of: 1 International Court of Justice, Press Communique 98/35, 2 November 1998. -

Discrimination and Violence Against Women in Brunei Darussalam On

SOUTH Muara CHINA Bandar Seri SEA Begawan Tutong Bangar Seria Kuala Belait Sukang MALAYSIA MALAYSIA I N D 10 km O N E SIA Discrimination and Violence Against Women in Brunei Darussalam on the Basis of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Presented to the 59th Session of The Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) Discrimination and Violence Against Women in Brunei Darussalam on the Basis of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Presented to the 59th Session of The Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) November 2014 • Geneva Submitted by: International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC) Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 Syariah Penal Code Order 2013 ................................................................................................................... 1 Discrimination Against LBT Women (Articles 1 and 2) ............................................................................. 3 Criminalization of Lesbians and Bisexual Women ...................................................................................... 3 Criminalization of Transgender Persons ..................................................................................................... -

Evaluation, Coordination and Execution: an Analysis of Military Coup Agency at Instances of Successful Coup D’État

School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Political Science Master’s Thesis Evaluation, Coordination and Execution: An Analysis of Military Coup Agency at Instances of Successful Coup D’état A Master’s Thesis Submitted to The Department of Political Science In Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts By Karim Ezzat El-Baz Under the supervision of Professor Dr. Holger Albrecht Associate Professor Political Science Department ! ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Professor Dr. Holger Albrecht for the useful comments, remarks and engagement through the learning process of this master thesis. Furthermore I would like to thank him for introducing me to the topic as well for the support on the way. Also, I would like to thank my readers Professor Dr. Oliver Schlumberger & Professor Dr. Marie Duboc at Tübingen University and Professor Dr. Marco Pinfari at The American University in Cairo for their outstanding help and engagement. Finally, I would like to thank my loved ones, who have supported me throughout entire process, both by keeping me harmonious and helping me putting pieces together. I will be grateful forever for your love. ! I! For Mom, Dad, Wessam & C.M.E.P.S! ! II! TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Acknowledgment……………………………………………………………………………………….I Dedication……………………………………………………………………………………………....II CHAPTERS CHAPTER 1 – Introduction……………………………………………………………….....................2 CHAPTER 2 – Theory…………………………………………………………………………………10 CHAPTER 3 – Military Coup Agency Dataset………………………………………………………...24 CHAPTER 4 – Instances of Mixed Military Coups D’état: Thailand 1991 and Turkey 1980………...46 Chapter 5 – Instances of Infantry Military Coups D’état: Haiti 1991 and Niger 2010………………...59 CHAPTER 6 – Summary, Conclusion, Recommendation……………………………………………..72 Codebook……………………………………………………………………………………………….78 Dataset………………………………………………………………………………………………….79 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………………82! “A military with no political training is a potential criminal.” Cpt. -

The Malaysian Economy in Figures Revised As at June 2020 2020

The Malaysian Economy in Figures Revised as at June 2020 2020 Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department The Malaysian Economy in Figures 2020 Prepared by the Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department Phone : 03-8000 8000 Fax : 03-8888 3798 Website : www.epu.gov.my Background on Malaysia • Malaysia covers an area of 330,535 square kilometers and lies entirely in the equatorial zone, with the average daily temperature throughout Malaysia varying between 21C to 32C. It is made of 13 states, namely Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Melaka, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, Pulau Pinang, Perak, Perlis, Selangor, Terengganu and Sabah and Sarawak on the island of Borneo as well as the three Federal Territories of Kuala Lumpur, Labuan and Putrajaya. • Malaysia is a multi-ethnic country with the predominant ethnic groups in Peninsular Malaysia being Malay, Chinese and Indian. In Sabah and Sarawak, the indigenous people represents the majority, which includes Kadazan-Dusun, Bajau and Murut in Sabah as well as Iban, Bidayuh and Melanau in Sarawak. • The Government of Malaysia is led by a Prime Minister and a constitutional monarchy, which employs a Parliamentary system. It has three branches of government - the Executive, the Legislature and the Judiciary. • The Malaysian Parliament is made up of His Majesty Yang di-Pertuan Agong, the Senate (Upper House) with 70 members and the House of Representatives (Lower House) with 222 members. Out of the 70 senators in the Senate, 44 are appointed by His Majesty Yang di-Pertuan Agong while 26 are elected by the State legislatures. The general election for the 222 members of the Lower House must be held every five years. -

The Lifecycle of Sri Lanka Malay

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HKU Scholars Hub Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 7 (January 2014) Language Endangerment and Preservation in South Asia, ed. by Hugo C. Cardoso, pp. 100-118 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp07 5 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24605 The lifecycle of Sri Lanka Malay Umberto Ansaldo & Lisa Lim The University of Hong Kong The aim of this paper is to document the forces that led first to the decay and then the revival of the ancestral language of the Malay diaspora of Sri Lanka. We first sketch the background of the origins of the language in terms of intense contact and multilingual transfer; then analyze the forces that led to a significant language shift and consequent loss, as well as the factors responsible for the recent survival of the language. In doing so we focus in particular on the ideologies of language upheld within the community, as well as on the role of external agents in the lifecycle of the community. 1. THE FORMATIVE PERIOD. The community of Malays in Sri Lanka1 is the result of the central practices of Western colonialism, namely the displacement of subjects from one colonized region to another. Through various waves of deportation communities of people from Indonesia (the 1 Fieldwork undertaken in February and December 2003 and January 2004 in Colombo, Hambantota and Kirinda was partially supported by a National University of Singapore Academic Research Grant (R-103-000-020-112) for the project Contact languages of Southeast Asia: The role of Malay (Principal investigator: Umberto Ansaldo).