The Thai-Lao Border Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

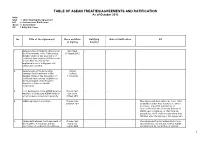

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Older Population and Health System: a Profile of Thailand

Older Population and Health System: A profile of Thailand I. Introduction to Thailand The Kingdom of Thailand was established in the mid-14th Century, known as Siam until 1939. A revolution in 1932 led to a constitutional monarchy. It lies in the heart of Southeast Asia. The country shares a long border with Myanmar to the west and the north, Lao P.D.R. to the north and the northeast, Cambodia to the east and Malaysia to the south. Thailand is divided into four distinct geographical regions: the mountainous North, the fertile Central Plains, the semi-arid plateau of the Northeast and the peninsula South At present, there are around 62.3 million people, of which 32% live in urban areas. Although most of Thailand is agricultural, the social and economic developments have changed the economy rapidly to industrialized productions and service sectors. After enjoying the world’s highest growth rate from 1985 to 1995 – averagely almost 9% annually – increased speculative pressure on Thailand currency in 1997 led to a crisis that uncovered financial sector weakness and forced the government to float the value of the Baht. Thailand entered a economic recovery stage in 1999. Nevertheless, the economic ordeal has a significant impact on country’s labor structure, population migration, urbanization and life styles. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per Capita is $7,248 in 2002. GDP- composition by sector is 11% in agriculture sector, 40% in industry and 49% in services. Average consumer price index (CPI) in 2001 is only 1.6%. The CPI in food and non-food are 0.4% and 2.2% respectively. -

Curriculum Vitae Stanley Mays Arua

CURRICULUM VITAE STANLEY MAYS ARUA Personal Details SURNAME : ARUA GIVEN NAMES : STANLEY MAYS BIRTH DATE : 29th June 1972 HOME DISTRICT/PROV : Bereina, Central Province, PNG MARITAL STATUS : Married with 8 children RESIDENTIAL ADDRESS : S239 L24: Gerehu Stg 2. NCD. CONTACT PHONE : 3019233: Email: : [email protected] Current Status: Coordinator – Program Compliance Development Partner Compliance & Coordination Unit Department of Prime Minister & NEC Academic Qualifications Post Graduate Diploma of Arts in Political Science and International Relations – Research -, Auckland University, NZ, 1999 Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and International Relations, University of PNG, 1998 Matriculation in Social Science – Education Faculty, University of PNG, 1995 Grade 10 Certificate, De La Salle Bomana, National Capital District, Department of Education, 1988 Special Training Professional Program for Diplomats from Pacific Island Countries, Ministry of Commerce (Certificate June 2011) People’s Republic of China. International Program on Public Administration and Good Governance, KOICA (Certificate November 2008) Republic of Korea Foreign Service Training, PNGDFAT/NZMFAT (Certificate July 2008) Port Moresby, PNG Time Management and Delegation, PNG Bankers’ College (Certificate 2002) Port Moresby, PNG 1 Positive Work Attitudes, Dept. Labour and Industrial Relations, (Certificate 2001) PNG Public Service, Port Moresby Small Business Management, Ausbiz Limited (Certificate 1999) AusAid Secretary to the University of the South Pacific -

Fact Sheet – Thailand Official Name Kingdom of Thailand Capital Bangkok

Fact Sheet – Thailand Official Name Kingdom of Thailand Capital Bangkok (population 10 million) Area 513,115 sq km (about 1/6th of area of India) Provinces 77 provinces including one Specially Governed District (Bangkok) Major cities Bangkok, Chiang Mai, Phuket, Khon Kaen, Nakorn Ratchasima, Ubon Ratchathanee, Hat Yai and Udon Thani Population 67.09 million (July 2012) population growth rate – 0.7% per annum Religion Buddhist 95%, Muslims 3.8%, Christians 0.5%, others 1.7%. Ethnic Groups Thais, Chinese, Malays, the Burmese, Lao, Khmers Currency Baht (1 US$ - 29.45 Baht - May 2013) National Day 5 December (Birthday of HM King Bhumibol Adulyadej) Languages Thai, Chinese, English Climate Tropical: temperatures vary between 19 C to 38 C Government Constitutional Monarchy with Parliamentary Democracy Head of State HM Bhumibol Adulyadej, the 9thking (Rama IX) of the House of Chakri, is the world's longest-serving ruler (since 1946). The king is titled as the upholder of the Buddhist religion & the defender of all faiths. Crown Prince is HRH Mahavajiralongkorn. Head of PM Yingluck Shinawatra (since August 2011), Thailand’s first female Government PM and the 28th PM of Thailand, member of the Pheu Thai Party Parliament The National Assembly of Thailand is a bicameral body. The Senate (National (Upper House) is a non-partisan legislative chamber, composed of 150 Assembly) members (76 Senators are directly elected from the Provinces, while 74 are appointed from various sectors by the Senate Selection Committee). The Senate operates under fixed terms of 6 years. The House of Representatives (Lower House) with a 4 years term has a total 500 Members (375 Members are elected through single constituency elections, while the other 125 are appointed on the basis of percentage of votes obtained by each party. -

Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty

The Asian Development Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development do not guarantee the accuracy of this document and accept no responsibility whatsoever for any consequences of its use. This document was obtained in September 2007. Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 2 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 3 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 4 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 5 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 6 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 7 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 www.oecd.org/corruption/asiapacific/mla [email protected] Philippines-Thailand Extradition Treaty 8 ADB/OECD Anti-Corruption Initiative for Asia Pacific September 2007 -

Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement Between Thailand and Indonesia

Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement between Thailand and Indonesia Completed in 2000 This document was downloaded from ASEAN Briefing (www.aseanbriefing.com) and was compiled by the tax experts at Dezan Shira & Associates (www.dezshira.com). Dezan Shira & Associates is a specialist foreign direct investment practice, providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in emerging Asia. AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE KINGDOM OF THAILAND AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME The Government of the Kingdom of Thailand and the Government of the Republic of Indonesia, DESIRING to conclude an Agreement for the avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion with respect to taxes on income, HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS : Article 1 PERSONAL SCOPE This Agreement shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States. 2 Article 2 TAXES COVERED 1. This Agreement shall apply to taxes on income imposed on behalf of one of the Contracting States, irrespective of the manner in which they are levied. 2. There shall be regarded as taxes on income all taxes imposed on total income or on elements of income, including taxes on gains from the alienation of movable or immovable property, taxes on the total amounts of wages or salaries paid by enterprises, as well as taxes on capital appreciation. 3. The existing taxes to which the Agreement shall apply are: (a) in Thailand : (i) the Income Tax; (ii) the Petroleum income Tax. -

3 History of Thailand in Brief in Order to Understand the Culture of a State, It Is Necessary to Trace Back Different Eras of the History of That State

3 History of Thailand in Brief In order to understand the culture of a state, it is necessary to trace back different eras of the history of that state. The history of Thailand begins 5,000 years ago; the ancestors of today’s Thai people lived in southern China areas. Through various migration streams they worked their way south to Thailand, Burma and Laos. They entered the Southeast Asian peninsular, today’s Thailand at Chiang Saen, on the southern banks of Mekong River. It was the migrants from southern China who formed the first city states in the northern regions of present day Thailand.32 3.1 The Origin of Thai People and Historical Development According to Noppawan Sirivejkul33 the Thai historical development may be divided into 9 eras which can be briefly summarized as follows: Table 15: Division of Thai Historical Eras Era or Kingdom Century A.D. Important Development 1. Funan Kingdom 1st – 6th 43 B.C.- 557 A.D. Mekong Basin Settlement 2. Dvaravati Kingdom 6th – 11th 557 - 1057 Influence of Indian Culture 3. Lawo (Lopburi) 10th – 12th 957 - 1157 Era of Disputes 4. Haripunchai (Lamphun) 7th - 13th 657 - 1292 Religious Development Era 5. Lanna Kingdom 13th – 16th 1296 - 1355 Kingdom Establishment Age 1355 – 1525 Golden Age of Lanna 1525 - 1558 Lanna Age of Decline 6. Sukhothai Kingdom 12th - 15th 1157 - 1438 Pottery, Celadon Age 7. Ayutthaya Kingdom 14th – 18th 1350 - 1767 417 years of Prosperity 8. Thonburi 18th 1767 - 1782 15 years of Reconstruction 9. Rattanakosin (Bangkok) 18th - Present 1782 - 1851 Chakri Dynasty Era 1851 – 1932 Political Reform 1932 - Present Democratic Ruling Source: Noppawan Sirivejkul. -

Modern History of Thailand

01999032: History Part II Modern History of Thailand Modernization to Globalization 1 Modern History of Thailand Modernization to Globalization 2 Chulalongkorn: the modernizer • 1853-1910 • Modernization/ Westernization • 1897 First visit to Europe • 1907 Second visit to Europe • Strategy to avoid colonization 3 Refashioning Siam • Uniform • Western Schooling • Abolishing slavery • Collecting new objects • Western army King Chulalongkorn (1 Oct. 1868 – 23 Oct.1910) Phra Bat Somdet Phra Poraminthra Maha Chulalongkorn Phra Chunla Chom Klao Chao Yu Hua, or Rama V, was the fifth monarch of Siam under the House of Chakri. He was known to the Siamese of his time as Phra Phuttha Chao Luang. Wikipedia 4 Chakri Throne Hall 5 Internal-colonization • Anglo-Siam treaty over Chiang Mai in 1874 • Railway expansion • Phumibun revolt (Millenarian movement) • Survey of provinces 6 Paknam Incident • French gunboats threatened Bangkok, 1893 • Territorial “lost” 7 Road-Rail-Steamboat • Chareonkrung road • Hualamphong station • East Asiatic Port 8 Dusit Palace • New palace complex for absolutist monarch • Equestrian monument 9 Official Nationalism • Vajiravudh and the creation of Nation • Burmese: external enemy/ Chinese: internal enemy • Jews of the East • Nationality Act and Surname Act King Vajiravudh (23 Oct. 1910 – 25 Nov. 1925) Phra Bat Somdet Phra Poramentharamaha Vajiravudh Phra Mongkut Klao Chao Yu Hua or Rama VI (1 January 1880 – 25 November 1925), was the sixth monarch of Siam under the House of Chakri, ruling from 1910 until his death. King Vajiravudh is known for his efforts to create and promote Siamese nationalism. His reign was characterized by Siam's movement further towards democracy and minimal participation in World War I. -

Comparing Regime Continuity and Change: Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Australian National University REGIME CHANGE AND REGIME MAINTBNANCB IN ASllA ANDTHE PACIFIC Discussion Paper No.15 Comparing Regime Continuity and Change: Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia WILLIAM CASE Published by TheDepartment of Politicaland SocialChange Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University 1995 REGIME CHANGE AND REGIME MAINTENANCE IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC In recent years there have beensome dramaticchanges of politicalleadership in the Asia-Pacificregion, and also some dramaswithout leadershipchange. In a few countriesthe demiseof well-entrenched politicalleaders appearsimmi nent; in others regular processes of parliamentary government still prevail. These differing patterns of regime change and regime maintenance raise fundamental questions about the nature of political systems in the region. Specifically,how have some politicalleaders or leadershipgroups been able to stay in power for relatively long periods and why have they eventually been displaced? What are the factors associated with the stability or instability of political regimes? What happens when longstanding leaderships change? The Regime Change and Regime Maintenance in Asia and the Pacific Project will address these and other questions from an Asia-Pacific regional perspectiveand at a broadertheoretical level. The project is under the joint direction of DrR.J. May and DrHarold Crouch. For furtherinformation aboutthe project write to: The Secretary Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies (RSPAS) The AustralianNational University CanberraACT 0200 Australia ©Departmentc:i fbliticalChange, andSocial Research ScOOol c:i Pacificand Asian Studies, TheAustralian National University, 1995. Apartfrom any fair dealings forthe purposeof study, criticism or review, aspermitted under the Copyright Act, no partmay be reproduced by any processwithout written permission. -

17 VISA and ENTRY REQUIREMENTS for THAILAND (According to Information Provided by the Host Country)

Annex F VISA AND ENTRY REQUIREMENTS FOR THAILAND (according to information provided by the host country) COUNTRIES WHOSE CITIZENS DO NOT REQUIRE A VISA TO ENTER THAILAND 1. TOURIST VISA EXEMPTION According to the Interior Ministerial Announcements dated 6 February B.E. 2538 (1995), 8 December B.E. 2541 (1998), 1 October B.E. 2545 (2002) and 20 December B.E. 2545 (2002), passport holders from 39 countries do not require a visa when entering Thailand for tourism purposes if their stay in the Kingdom does not exceed 30 days. The applicant must possess instrument of means of living expenses 10,000 Baht per person and 20,000 Baht per family accordingly. Please be advised that ordinary passport holders of 39 countries who intend to engage in certain activities are eligible to apply for a visa when entering the Kingdom if their qualifications meet the conditions set forth by the Office of Immigration Bureau. For more information, please contact the Office Of Immigration Bureau, Soi Suan Plu, off South Sathorn Road, Bangkok 10120, Tel. (626) 287-3101-10 or at website http://police.go.th. A I P Australia Indonesia Peru Austria Ireland The Philippines Israel Portugal Italy B J Q Belgium Japan Qatar Brazil Bahrain Brunei Darussalam C K S Canada Korea Singapore Kuwait Spain South Africa Sweden Switzerland D L T Denmark Luxembourg Turkey F M U Finland Malaysia United Arab Emirates France United Kingdom United States of America G N V Germany The Netherlands Vietnam Greece New Zealand Norway H Hong Kong 17 2. TEMPORARY TOURIST VISA: VISA ON ARRIVAL According to the Interior Ministerial Announcements, passport holders from 14 countries may apply for visas at the immigration checkpoints for the purpose of tourism for the period of not exceeding 15 days. -

AYUTTHAYA, THAILAND Ayutthaya, Thailand © Center for the Study of Global Christianity, 2020

AYUTTHAYA, THAILAND Ayutthaya, Thailand © Center for the Study of Global Christianity, 2020 Cover Photo: Woman and children at the Festival of Light, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, Thai- land. Unsplash: Guille Álvarez Unless otherwise noted, data is sourced from the World Christian Database and the fol- lowing citation should be used: Todd M. Johnson and Gina A. Zurlo, eds., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, accessed December 2019). ABOUT THE CSGC The Center for the Study of Global Christianity is an academic research center that mon- itors worldwide demographic trends in Christianity, including outreach and mission. We provide a comprehensive collection of information on the past, present, and future of Christianity in every country of the world. Our data and publications help churches, mission agencies, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to be more strategic, thoughtful, and sensitive to local contexts. Please visit our website at www.globalchristianity.org. DATA AND TERMS This dossier includes many technical terms related to the presentation of statistics. A complete methodology document is found here: https://www.gordonconwell.edu/ center-for-global-christianity/research/dossiers. We use a social scientific method for measuring religion around the world; namely, self-identification. If a person calls herself a Christian, then she is a Christian. We measure Christians primarily by denominational affiliation in every country of the world and these data are housed in the World Christian Database. Ethnolinguistic people groups are distinct homogeneous ethnic or racial groups within a single country, speaking its own language (one single mother tongue). These dossiers measure gospel access (also known as “evangelization”) by a number of variables, including but not limited to, evangelistic outreach, church planting, personal witnessing, sharing on social media, etc. -

Agreement Between the Government of the Kingdom of Thailand and the Government of Malaysia for the Avoidance of Double Taxation

AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE KINGDOM OF THAILAND AND THE GOVERNMENT OF MALAYSIA FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME The Government of the Kingdom of Thailand and the Government of Malaysia Desiring to conclude an Agreement for the avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion with respect to taxes on income, Have agreed as follows: CHAPTER I SCOPE OF THE AGREEMENT ARTICLE 1 PERSONAL SCOPE This Agreement shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States. ARTICLE 2 TAXES COVERED 1. This Agreement shall apply to taxes on income imposed by each Contracting State, irrespective of the manner in which they are levied. 2. The existing taxes to which the Agreement shall apply are: (a) in the case of Malaysia: (i) the income tax and excess profit tax; (ii) the supplementary income taxes, that is, tin profits tax, development tax and timber profits tax; and (iii) the petroleum income tax; (hereinafter referred to as "Malaysian tax"); (b) in the case of Thailand: (i) the income tax; (ii) the petroleum income tax; (hereinafter referred to as "Thai tax"). 3. The Agreement shall also apply to any identical or substantially similar taxes on income which are imposed after the date of signature of this Agreement in addition to, or in place of, the existing taxes. The competent authorities of the Contracting States shall notify each other of important changes which have been made in their respective taxation laws. CHAPTER II DEFINITIONS ARTICLE 3 GENERAL DEFINITIONS 1.