Thailand Bound: an Exploration of Labor Migration Infrastructures in Cambodia, Myanmar, and Lao PDR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Leterature Review

CHAPTER 2 LETERATURE REVIEW The contents in this chapter were divided into five parts as follows: 1. Data from Aranyaprathet Customs House 2. A description of Ban Klongluek Border Market 3. Stressor 4. Stress 4.1 Definition of stress 4.2 The concept of stress 4.3 Stress evaluation 4.4 Stress related outcomes 5. Stress management 5.1 The concept of coping 5.2 The concept of stress management Data from Aranyaprathet Customs House The data from Information and Communication Technology, by the cooperation of Thailand Custom House indicates that overall business on the borderland of Thailand have increased every year by millions of baht since 1997. Comparison between all Thailand -Cambodia business shows borderland International business is 75% of all International business between Thailand and Cambodia as show table 2-1. Borderland businesses are mainstays of economy in this area of country. Sakaeo Province is an eastern province of Thailand where has the boundary contacts with the Cambodia. In 2007, Aranyaprathet Custom House and Chanthaburi Custom House had total trade value 18,468 and 14,432 million baht, respectively. This market has a lot of tourists, about 10,000 persons per day, circulating funds of about 100-200 million baht as show table 2-2 and table 2-3. 10 Table 2-1 Comparison between International business is Thailand-Cambodia business and Thailand -Cambodia business borderland (1997-2007) Year International Border Line Amount* % Amount* % 1997 11,825 100 8,271 70 1998 13,413 100 10,041 75 1999 13,939 100 10,496 75 2000 14,230 -

The Provincial Business Environment Scorecard in Cambodia

The Provincial Business Environment Scorecard in Cambodia A Measure of Economic Governance and Regulatory Policy November 2009 PBES 2009 | 1 The Provincial Business Environment Scorecard1 in Cambodia A Measure of Economic Governance and Regulatory Policy November 2009 1 The Provincial Business Environment Scorecard (PBES) is a partnership between the International Finance Corporation and the donors of the MPDF Trust Fund (the European Union, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Switzerland), and The Asia Foundation, with funding support from Danida, DFID and NZAID, the Multi-Donor Livelihoods Facility. PBES 2009 | 3 PBES 2009 | 4 Table of Contents List of Tables ..........................................................................................................................................................iii List of Figures .........................................................................................................................................................iv Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................................v Acknowledgments .....................................................................................................................................................vi 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1. PBES Scorecard and Sub-indices .......................................................................................... -

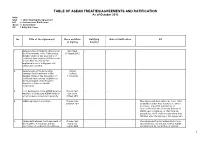

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Collaborative Exploration of Solanaceae Vegetable Genetic Resources in Southern Cambodia, 2017

〔AREIPGR Vol. 34 : 102-117, 2018〕 doi:10.24514/00001134 Original Paper Collaborative Exploration of Solanaceae Vegetable Genetic Resources in Southern Cambodia, 2017 Hiroshi MATSUNAGA 1), Makoto YOKOTA 2), Mat LEAKHENA 3), Sakhan SOPHANY 3) 1) Institute of Vegetable and Floriculture Science, NARO, Kusawa 360, Ano, Tsu, Mie 514-2392, Japan 2) Kochi Agriculture Research Center, 1100, Hataeda, Nangoku, Kochi 783-0023, Japan 3) Cambodian Agricultural Research and Development Institute, National Road 3, Prateahlang, Dangkor, P. O. Box 01, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Communicated by K. FUKUI (Genetic Resources Center, NARO) Received Nov. 1, 2018, Accepted Dec. 14, 2018 Corresponding author: H. MATSUNAGA (Email: [email protected]) Summary The National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO) and the Cambodian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (CARDI) have collaborated since 2014 under the Plant Genetic Resources in Asia (PGRAsia) project to survey the vegetable genetic resources available in Cambodia. As part of this project, three field surveys of Solanaceae crops were conducted in November 2014, 2015 and 2016 in western, eastern and northern Cambodia, respectively. In November 2017, we conducted a fourth field survey in southern Cambodia, including the Svay Rieng, Prey Veng, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Kou Kong, Sihanoukville, Kampot and Takeo provinces. We collected 56 chili pepper (20 Capsicum annuum, 36 C. frutescens) and 4 eggplant (4 Solanum spp.) fruit samples from markets, farmers’ yards, farmers’ fields and an open space. After harvesting seeds from the collected fruits, the seeds were divided equally and half were conserved in the CARDI and the other half were transferred to the Genetic Resource Center, NARO using the standard material transfer agreement (SMTA). -

Nong Khai Nong Khai Nong Khai 3 Mekong River

Nong Khai Nong Khai Nong Khai 3 Mekong River 4 Nong Khai 4 CONTENTS HOW TO GET THERE 7 ATTRACTIONS 9 Amphoe Mueang Nong khai 9 Amphoe Tha Bo 16 Amphoe Si Chiang Mai 17 Amphoe Sangkhom 18 Amphoe Phon Phisai 22 Amphoe Rattanawapi 23 EVENTS AND FESTIVALS 25 LOCAL PRODUCTS 25 SOUVENIR SHOPS 26 SUGGESTED ITINERARY 26 FACILITIES 27 Accommodations 27 Restaurants 30 USEFUL CALLS 31 Nong Khai 5 5 Wat Aranyabanpot Nong Khai 6 Thai Term Glossary a rebellion. King Rama III appointed Chao Phraya Amphoe: District Ratchathewi to lead an army to attack Vientiane. Ban: Village The army won with the important forces Hat: Beach supported by Thao Suwothanma (Bunma), Khuean: Dam the ruler of Yasothon, and Phraya Chiangsa. Maenam: River The king, therefore, promoted Thao Suwo to Mueang: Town or City be the ruler of a large town to be established Phrathat: Pagoda, Stupa on the right bank of the Mekong River. The Prang: Corn-shaped tower or sanctuary location of Ban Phai was chosen for the town SAO: Subdistrict Administrative Organization called Nong Khai, which was named after a very Soi: Alley large pond to the west. Song Thaeo: Pick-up trucks but with a roof Nong Khai is 615 kilometres from Bangkok, over the back covering an area of around 7,332 square Talat: Market kilometres. This province has the longest Tambon: Subdistrict distance along the Mekong River; measuring Tham: Cave 320 kilometres. The area is suitable for Tuk-Tuks: Three-wheeled motorized taxis agriculture and freshwater fishery. It is also Ubosot or Bot: Ordination hall in a temple a major tourist attraction where visitors can Wihan: Image hall in a temple easily cross the border into Laos. -

Transport Logistics

MYANMAR TRADE FACILITATION THROUGH LOGISTCS CONNECTIVITY HLA HLA YEE BITEC , BANGKOK 4.9.15 [email protected] Total land area 677,000sq km Total length (South to North) 2,100km (East to West) 925km Total land boundaries 5,867km China 2,185km Lao 235km Thailand 1,800km Bangladesh 193km India 1,463km Total length of coastline 2,228km Capital : Naypyitaw Language :Myanmar MYANMAR IN 2015 REFORM & FAST ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS SIGNIFICANT POTENTIAL CREDIBILITY AMONG ASEAN NATIONS GATE WAY “ CHINA & INDIA & ASEAN” MAXIMIZING MULTIMODALTRANSPORT LINKAGES EXPEND GMS ECONOMIC TRANSPORT CORRIDORS EFFECTIVE EXTENSION INTO MYANMAR INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTION TRADE AND LOTISGICS SUPPLY CHAIN TRANSPARENCY & PREDICTABILITY LEGAL & REGULATORY FREAMEWORK INFRASTUCTURE INFORMATION CORRUPTION FIANACIAL SERVICE “STRENGTHEING SME LOGISTICS” INDUSTRIAL ZONE DEVELOPMENT 7 NEW IZ KYAUk PHYU Yadanarbon(MDY) SEZ Tart Kon (NPD) Nan oon Pa han 18 Myawadi Three pagoda Existing IZ Pon nar island Yangon(4) Mandalay Meikthilar Myingyan Yenangyaing THI LA WAR Pakokku SEZ Monywa Pyay Pathein DAWEI Myangmya SEZ Hinthada Mawlamyaing Myeik Taunggyi Kalay INDUSTRIES CATEGORIES Competitive Industries Potential Industries Basic Industries Food and Beverages Automobile Parts Agricultural Machinery Garment & Textile Industrial Materials Agricultural Fertilizer Household Woodwork Minerals & Crude Oil Machinery & spare parts Gems & Jewelry Pharmaceutical Electrical & Electronics Construction Materials Paper & Publishing Renewable Energy Household products TRANSPORT -

The Transport Trend of Thailand and Malaysia

Executive Summary Report The Potential Assessment and Readiness of Transport Infrastructure and Services in Thailand for ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) Content Page 1. Introduction 1.1 Rationales 1 1.2 Objectives of Study 1 1.3 Scopes of Study 2 1.4 Methodology of Study 4 2. Current Status of Thailand Transport System in Line with Transport Agreement of ASEAN Community 2.1 Master Plan and Agreement on Transport System in ASEAN 5 2.2 Major Transport Systems for ASEAN Economic Community 7 2.2.1 ASEAN Highway Network 7 2.2.2 Major Railway Network for ASEAN Economic Community 9 2.2.3 Main Land Border Passes for ASEAN Economic Community 10 2.2.4 Main Ports for ASEAN Economic Community 11 2.2.5 Main Airports for ASEAN Economic Community 12 2.3 Efficiency of Current Transport System for ASEAN Economic Community 12 3. Performance of Thailand Economy and Transport Trend after the Beginning of ASEAN Economic Community 3.1 Factors Affecting Cross-Border Trade and Transit 14 3.2 Economic Development for Production Base Thriving in Thailand 15 3.2.1 The analysis of International Economic and Trade of Thailand and ASEAN 15 3.2.2 Major Production Bases and Commodity Flow of Prospect Products 16 3.2.3 Selection of Potential Industries to be the Common Production Bases of Thailand 17 and ASEAN 3.2.4 Current Situation of Targeted Industries 18 3.2.5 Linkage of Targeted Industries at Border Areas, Important Production Bases, 19 and Inner Domestic Areas TransConsult Co., Ltd. King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi 2T Consulting and Management Co., Ltd. -

Drug Trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle

Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy To cite this version: Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy. Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle. An Atlas of Trafficking in Southeast Asia. The Illegal Trade in Arms, Drugs, People, Counterfeit Goods and Natural Resources in Mainland, IB Tauris, p. 1-32, 2013. hal-01050968 HAL Id: hal-01050968 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01050968 Submitted on 25 Jul 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Atlas of Trafficking in Mainland Southeast Asia Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy CNRS-Prodig (Maps 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 25, 31) The Golden Triangle is the name given to the area of mainland Southeast Asia where most of the world‟s illicit opium has originated since the early 1950s and until 1990, before Afghanistan‟s opium production surpassed that of Burma. It is located in the highlands of the fan-shaped relief of the Indochinese peninsula, where the international borders of Burma, Laos, and Thailand, run. However, if opium poppy cultivation has taken place in the border region shared by the three countries ever since the mid-nineteenth century, it has largely receded in the 1990s and is now confined to the Kachin and Shan States of northern and northeastern Burma along the borders of China, Laos, and Thailand. -

The Thai-Lao Border Conflict

ERG-IO NOT FOR PUBLICATION WITHOUT WRITER'S CONSENT INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS 159/1 Sol Mahadlekluang 2 Raj adamri Road Bangkok February 3, 1988 Siblinq Rivalry- The Thai-Lao Border Conflict Mr. Peter Mart in Institute of Current World Affairs 4 West Wheelock Street Hanover, NH 03755 Dear Peter, The Thai Army six-by-six truck strained up the steep, dirt road toward Rom Klao village, the scene of sporadic fighting between Thai and Lao troops. Two days before, Lao "sappers" had ambushed Thai soldiers nearby, killing II. So, as the truck crept forward with the driver gunning the engine to keep it from stalling, I was glad that at least this back road to the disputed mountaintop was safe. For the past three months, reports of Thai and Lao soldiers battling to control this remote border area have filled the headlines of the local newspapers. After a brief lull, the conflict has intensified following the Lao ambush on January 20. The Thai Army says that it will now take "decisive action" to drive the last Lao intruders from the Rom Klao area, 27 square miles of land located some 300 miles northeast of Bangkok. When Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda visited the disputed tract, the former cavalry officer dramatically staked out Thai territory by posing in combat fatigues, cradling a captured Lao submachine gun. Last week, the Thai Foreign Ministry escorted some 40 foreign diplomats to the region to butress the Thai claim, but had to escort them out again when a few Lao artillery shells fell nearby. -

Grid Reinforcement Project

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number: 53324-001 August 2020 Proposed Loan and Administration of Grants Kingdom of Cambodia: Grid Reinforcement Project Distribution of this document is restricted until it has been approved by the Board of Directors. Following such approval, ADB will disclose the document to the public in accordance with ADB’s Access to Information Policy. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 16 July 2020) Currency unit – riel/s (KR) KR1.00 = $0.00024 $1.00 = KR4,096 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BESS – battery energy storage system CEF – Clean Energy Fund COVID-19 – coronavirus disease EDC – Electricité du Cambodge EMP – environmental management plan LARP – land acquisition and resettlement plan MME Ministry of Mines and Energy PAM – project administration manual SCF – Strategic Climate Fund TA – technical assistance WEIGHTS AND MEASURES GWh – gigawatt-hour ha – hectare km – kilometer kV – kilovolt kWh – kilowatt-hour MW – megawatt GLOSSARY Congestion relief – Benefit of using battery energy storage system by covering peak loads exceeding the load carrying capacity of an existing transmission and distribution equipment Curtailment reserve – The capacity to provide power output in a given amount of time during power shortcuts and shortages Output smoothing – The process of smoothing power output to provide more stability and reliability of fluctuating energy sources Primary frequency – A crucial system which fixes the effects of power imbalance response between electricity -

Cambodia: Primary Roads Restoration Project

Performance Evaluation Report Reference Number: PPE:CAM 2009-57 Project Number: 28338 Loan Number: 1697 December 2009 Cambodia: Primary Roads Restoration Project Independent Evaluation Department CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – Cambodian riel (KR) At Appraisal At Project Completion At Independent Evaluation (August 1999) (July 2006) (March 2009) KHR1.00 = $0.000260 $0.000242 $0.000242 $1.00 = KR3,844.5 KR4,188.63 KR4,128.50 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AP – affected person AusAID – Australian Agency for International Development BME – benefit monitoring and evaluation COI – corridor of impact COMFREL – Committee for Free and Fair Election CDOH – Community Development Organization and Health Care DMS – detail measurement survey EFRP – Emergency Flood Rehabilitation Project EIRR – economic internal rate of return GDP – gross domestic product GMS – Greater Mekong Subregion ICB – international competitive bidding IED – Independent Evaluation Department IEE – initial environmental examination IRC – Inter-ministerial Resettlement Committee IRI – international roughness index km – kilometer Lao PDR – Lao People's Democratic Republic LCB – local competitive bidding m – meter MPWT – Ministry of Public Works and Transport NGO – nongovernment organization NR – national road (route nationale) NSDP – National Strategic Development Plan PCC – project coordination committee PCR – project completion report PPER – project performance evaluation report RAP – resettlement action plan RD – Resettlement Department ROW – right-of-way RRP – report and recommendation of the President RTAVIS – Road Traffic Accident Victim Information System STD – Sexually transmitted disease TA – technical assistance TCR technical assistance completion report VOC – vehicle operating costs NOTE In this report, “$” refers to US dollars Key Words asian development bank, development effectiveness, cambodia, performance evaluation, poverty reduction, national roads road maintenance, transport Director General : H. -

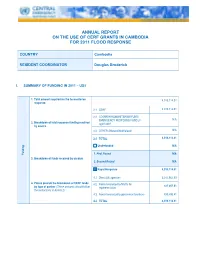

Annual Report on the Use of Cerf Grants in Cambodia for 2011 Flood Response

ANNUAL REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF GRANTS IN CAMBODIA FOR 2011 FLOOD RESPONSE COUNTRY Cambodia RESIDENT COORDINATOR Douglas Broderick I. SUMMARY OF FUNDING IN 2011 – US$ 1. Total amount required for the humanitarian 4,013,114.31 response 2.1 CERF 4,013,114.31 2.2 COMMON HUMANITARIAN FUND/ EMERGENCY RESPONSE FUND ( if N/A 2. Breakdown of total response funding received applicable ) by source 2.3 OTHER (Bilateral/Multilateral) N/A 2.4 TOTAL 4,013,114.31 Underfunded N/A Funding 1. First Round N/A 3. Breakdown of funds received by window 2. Second Round N/A Rapid Response 4,013,114.31 4.1 Direct UN agencies 3,011,961.39 4. Please provide the breakdown of CERF funds 4.2 Funds forwarded to NGOs for 167,657.51 by type of partner (These amounts should follow implementation the instructions in Annex 2) 4.3 Funds forwarded to government partners 833,495.41 4.4 TOTAL 4,013,114.31 II. SUMMARY OF BENEFICIARIES PER EMERGENCY Total number of individuals affected by the crisis Individuals Estimated 1.64 million Female 331,890 Male 308,515 Total number of individuals reached with CERF funding Total individuals (Female and male) 640,405 Of total, children under 5 182,656 III. GEOGRAPHICAL AREAS OF IMPLEMENTATION The CERF grant enabled a joint effort and a geographical area covering 17 of the 18 most-affected provinces with an estimated 640,000 beneficiaries. The most-affected provinces are located along the Tonle Sap and Mekong River, as indicated in the map below.