Board of Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Temple Dispute

International Journal of East Asian Studies, 23(1) (2019), 58-83. Dynamic Roles and Perceptions: The Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Temple Dispute Ornthicha Duangratana1 1 Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand This article is part of the author’s doctoral dissertation, entitled “The Roles and Perceptions of the Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs through Governmental Politics in the Temple Dispute.” Corresponding Author: Ornthicha Duangratana, Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand E-mail: [email protected] Received: 11 Feb 19 Revised: 16 Apr 19 Accepted: 15 May 19 58 Abstract Thailand and Cambodia have long experienced swings between discordant and agreeable relations. Importantly, contemporary tensions between Thailand and Cambodia largely revolve around the disputed area surrounding the Preah Vihear Temple, or Phra Vi- harn Temple (in Thai). The dispute over the area flared after the independence of Cambodia. This situation resulted in the International Court of Justice adjudicating the dispute in 1962. Then, as proactive cooperation with regards to the Thai-Cambodian border were underway in the 2000s, the dispute erupted again and became salient between the years 2008 to 2013. This paper explores the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ (MFA) perceptions towards the overlapping border claim since the Cold War and concentrates on the changes in perceptions in the period from 2008 to 2013 when the Preah Vihear temple dispute rekindled. Moreover, to study their implications on the Thai-Cambodian relations, those perceptions are analyzed in connection to the roles of the MFA in the concurrent Thai foreign-policy apparatus. Under the aforementioned approach, the paper makes the case that the internation- al environment as well as the precedent organizational standpoint significantly compels the MFA’s perceptions. -

Thailand White Paper

THE BANGKOK MASSACRES: A CALL FOR ACCOUNTABILITY ―A White Paper by Amsterdam & Peroff LLP EXECUTIVE SUMMARY For four years, the people of Thailand have been the victims of a systematic and unrelenting assault on their most fundamental right — the right to self-determination through genuine elections based on the will of the people. The assault against democracy was launched with the planning and execution of a military coup d’état in 2006. In collaboration with members of the Privy Council, Thai military generals overthrew the popularly elected, democratic government of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, whose Thai Rak Thai party had won three consecutive national elections in 2001, 2005 and 2006. The 2006 military coup marked the beginning of an attempt to restore the hegemony of Thailand’s old moneyed elites, military generals, high-ranking civil servants, and royal advisors (the “Establishment”) through the annihilation of an electoral force that had come to present a major, historical challenge to their power. The regime put in place by the coup hijacked the institutions of government, dissolved Thai Rak Thai and banned its leaders from political participation for five years. When the successor to Thai Rak Thai managed to win the next national election in late 2007, an ad hoc court consisting of judges hand-picked by the coup-makers dissolved that party as well, allowing Abhisit Vejjajiva’s rise to the Prime Minister’s office. Abhisit’s administration, however, has since been forced to impose an array of repressive measures to maintain its illegitimate grip and quash the democratic movement that sprung up as a reaction to the 2006 military coup as well as the 2008 “judicial coups.” Among other things, the government blocked some 50,000 web sites, shut down the opposition’s satellite television station, and incarcerated a record number of people under Thailand’s infamous lèse-majesté legislation and the equally draconian Computer Crimes Act. -

How Immigrants Contribute to Thailand's Economy

How Immigrants Contribute to Thailand’s Economy The effects of immigration on the Thai economy are considerable, as the number of Economy Thailand’s to Contribute Immigrants How immigrants has increased rapidly since the turn of the century. Immigrant workers now contribute to all economic sectors, and are important for the workforce in industrial How Immigrants Contribute sectors, such as construction and manufacturing, and in some service sectors, including private household services. Immigration in Thailand is associated with an improvement of labour market outcomes of the native-born population, and in particular appears to to Thailand’s Economy increase paid employment opportunities. Immigration is also likely to raise income per capita in Thailand, due to the relatively high share of the immigrant population which is employed and therefore contributes to economic output. Policies aiming to further diversify employment opportunities for immigrant workers could be benefi cial for the economic contribution of immigration. How Immigrants Contribute to Thailand’s Economy is the result of a project carried out by the OECD Development Centre and the International Labour Organization, with support from the European Union. The project aimed to analyse several economic impacts – on the labour market, economic growth, and public fi nance – of immigration in ten partner countries: Argentina, Costa Rica, Côte d’Ivoire, the Dominican Republic, Ghana, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, Rwanda, South Africa and Thailand. The empirical evidence stems from a combination of quantitative and qualitative analyses of secondary and in some cases primary data sources. Consult this publication on line at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264287747-en This work is published on the OECD iLibrary, which gathers all OECD books, periodicals and statistical databases. -

Major Developments in Thailand's Political Crisis

Major developments in Thailand’s political crisis More unrest and policy paralysis are likely as Thailand prepares for early elections. The country has suffered five years of political turbulence and sporadic street violence after former premier Thaksin Shinawatra was ousted in a 2006 coup. Thaksin currently commands a powerful opposition movement, standing in the way of current prime minister, Abhisit Vejjajiva. SET index GDP growth – % chg y/y 1200 15 1000 10 I 800 H O 5 D B PQ C G E F 600 J 0 N M 400 KL -5 A 200 -10 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2001 2008 cont... A January 6 J September Thaksin Shinawatra’s Thais Love Thais (Thai Rak Thai) party wins Samak found guilty of violating constitution by hosting TV cooking 248 of 500 seats in parliamentary election. shows while in office and had to quit. Somchai Wongsawat, Thaksin’s brother-in-law at the time, is elected prime minister by 2005 parliament. B February 6 K October 21 Thailand voters hand Thaksin Shinawatra a second term with The Supreme Court sentences Thaksin to two years in jail in expanded mandate. absentia for breaking a conflict-of-interest law. C September L November 25 Sondhi Limthongkul, a former Thaksin business associate, starts PAD protesters storm Bangkok’s main airport, halting all flights. Up the yellow-shirted People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) street to 250,000 foreign tourists are stranded. campaign to oust Thaksin. M December Constitutional Court disbands the PPP and bans Somchai from 2006 politics for five years for electoral fraud. -

Download This PDF File

“PM STANDS ON HIS CRIPPLED LEGITINACY“ Wandah Waenawea CONCEPTS Political legitimacy:1 The foundation of such governmental power as is exercised both with a consciousness on the government’s part that it has a right to govern and with some recognition by the governed of that right. Political power:2 Is a type of power held by a group in a society which allows administration of some or all of public resources, including labor, and wealth. There are many ways to obtain possession of such power. Demonstration:3 Is a form of nonviolent action by groups of people in favor of a political or other cause, normally consisting of walking in a march and a meeting (rally) to hear speakers. Actions such as blockades and sit-ins may also be referred to as demonstrations. A political rally or protest Red shirt: The term5inology and the symbol of protester (The government of Abbhisit Wejjajiva). 1 Sternberger, Dolf “Legitimacy” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (ed. D.L. Sills) Vol. 9 (p. 244) New York: Macmillan, 1968 2 I.C. MacMillan (1978) Strategy Formulation: political concepts, St Paul, MN, West Publishing; 3 Oxford English Dictionary Volume 1 | Number 1 | January-June 2013 15 Yellow shirt: The terminology and the symbol of protester (The government of Thaksin Shinawat). Political crisis:4 Is any unstable and dangerous social situation regarding economic, military, personal, political, or societal affairs, especially one involving an impending abrupt change. More loosely, it is a term meaning ‘a testing time’ or ‘emergency event. CHAPTER I A. Background Since 2008, there has been an ongoing political crisis in Thailand in form of a conflict between thePeople’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) and the People’s Power Party (PPP) governments of Prime Ministers Samak Sundaravej and Somchai Wongsawat, respectively, and later between the Democrat Party government of Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva and the National United Front of Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD). -

National Report of Thailand Convention on Nuclear

NATIONAL REPORT OF THAILAND CONVENTION ON NUCLEAR SAFETY The 8th Review Meeting Office of Atoms for Peace Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation August, 2019 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Reporting Article by Article 2 Article 6 Existing Nuclear Installations . 2 Article 7 Legislative and Regulatory Framework . 6 Article 8 Regulatory Body . 19 Article 9 Responsibility of the License Holder . 24 Article 10 Priority to Safety . 27 Article 11 Financial and Human Resources . 28 Article 12 Human Factors . 30 Article 13 Quality Assurance . 31 Article 14 Assessment and Verification of Safety . 33 Article 15 Radiation Protection . 34 Article 16 Emergency Preparedness . 35 Article 17 Siting . 42 Article 18 Design and Construction . 45 Article 19 Operation . 48 3 Appendix 54 I. List of Abbreviations . 55 1 1. Introduction Thailand deposited the instrument of accession for the Convention on Nuclear Safety (CNS) with the Director General of IAEA on July 3, 2018. Thailand has been a contracting party since October 1, 2018. Currently, Thailand does not have any nuclear installations. Its latest Power Development Plan (PDP) which was issued in 2018 no longer contains nuclear energy in its energy mix. However, Thailand had once included a nuclear power with different capacities in its previous three versions of PDP from 2007 to 2015. Thailand has only one research reactor, the Thai Research Reactor-1/Modification 1 (TRR-1/M1), which has been operated since the nuclear energy was first introduced to Thailand in 1962. Currently TRR-1/M1 is under operation of Thailand Institute of Nuclear Technology (TINT), which is a governmental public organization under Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research and Innovation. -

Bomb Planted at ASTV

Volume 17 Issue 20 News Desk - Tel: 076-273555 May 15 - 21, 2010 Daily news at www.phuketgazette.net 25 Baht The Gazette is published in association with Bomb planted at ASTV Leaders react to grenade at ‘yellow-shirt’ TV station PAPER bag contain- told the Gazette that the grenade INSIDE ing a live hand grenade was not the work of the red shirts. was found hanging “There is conflict within the Afrom the front door of PAD itself. For example, some the ASTV ‘yellow-shirt’ television PAD leaders have turned into network office in Phuket Town ‘multi-colors’. That’s a point to on May 11. consider, too,” he said. Bomb disposal police safely Phuket Provincial Police removed the device, an M67 Commander Pekad Tantipong said fragmentation grenade with its pin the act was probably the work of still in place, shortly after it was an individual or small group. discovered at 9am. It had been “I don’t believe this was wrapped in electrical tape and ordered by the red shirt leaders placed in a box inside a brown in Bangkok…I’m confident in Bank on Bird paper shopping bag that read saying this will not affect tour- As Ironman Les Bird’s Alpine “Save the World”. ism at all,” he said. climb nears, find out how he’s When detonated, an M67 Sarayuth Mallam, vice been preparing. has an average ‘casualty radius’ president of the Phuket Tourist Page 10 of 15 meters and a ‘fatality ra- Association, was less confident. dius’ of five meters; fragments CALM AND COLLECTED: A bomb disposal expert shows the M67 grenade. -

The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics by Zachary Abuza

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 6 The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics by Zachary Abuza Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Complex Operations, and Center for Strategic Conferencing. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, and publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Thai and U.S. Army Soldiers participate in Cobra Gold 2006, a combined annual joint training exercise involving the United States, Thailand, Japan, Singapore, and Indonesia. Photo by Efren Lopez, U.S. Air Force The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics By Zachary Abuza Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 6 Series Editors: C. Nicholas Rostow and Phillip C. Saunders National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. -

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar October 2020 About Us This report was written based on the information and data collection, monitoring, analytical insights and experiences with hate speech by civil society organizations working to reduce and/or directly af- fected by hate speech. The research for the report was coordinated by Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) and Progressive Voice and written with the assistance of the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School while it is co-authored by a total 19 organizations. Jointly published by: 1. Action Committee for Democracy Development 2. Athan (Freedom of Expression Activist Organization) 3. Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) 4. Generation Wave 5. International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School 6. Kachin Women’s Association Thailand 7. Karen Human Rights Group 8. Mandalay Community Center 9. Myanmar Cultural Research Society 10. Myanmar People Alliance (Shan State) 11. Nyan Lynn Thit Analytica 12. Olive Organization 13. Pace on Peaceful Pluralism 14. Pon Yate 15. Progressive Voice 16. Reliable Organization 17. Synergy - Social Harmony Organization 18. Ta’ang Women’s Organization 19. Thint Myat Lo Thu Myar (Peace Seekers and Multiculturalist Movement) Contact Information Progressive Voice [email protected] www.progressivevoicemyanmar.org Burma Monitor [email protected] International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School [email protected] https://hrp.law.harvard.edu Acknowledgments Firstly and most importantly, we would like to express our deepest appreciation to the activists, human rights defenders, civil society organizations, and commu- nity-based organizations that provided their valuable time, information, data, in- sights, and analysis for this report. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Intersection of Economic Development, Land, and Human Rights Law in Political Transitions: The Case of Burma THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Social Ecology by Lauren Gruber Thesis Committee: Professor Scott Bollens, Chair Associate Professor Victoria Basolo Professor David Smith 2014 © Lauren Gruber 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MAPS iv LIST OF TABLES v ACNKOWLEDGEMENTS vi ABSTRACT OF THESIS vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Historical Background 1 Late 20th Century and Early 21st Century Political Transition 3 Scope 12 CHAPTER 2: Research Question 13 CHAPTER 3: Methods 13 Primary Sources 14 March 2013 International Justice Clinic Trip to Burma 14 Civil Society 17 Lawyers 17 Academics and Politicians 18 Foreign Non-Governmental Organizations 19 Transitional Justice 21 Basic Needs 22 Themes 23 Other Primary Sources 23 Secondary Sources 24 Limitations 24 CHAPTER 4: Literature Review Political Transitions 27 Land and Property Law and Policy 31 Burmese Legal Framework 35 The 2008 Constitution 35 Domestic Law 36 International Law 38 Private Property Rights 40 Foreign Investment: Sino-Burmese Relations 43 CHAPTER 5: Case Studies: The Letpadaung Copper Mine and the Myitsone Dam -- Balancing Economic Development with Human ii Rights and Property and Land Laws 47 November 29, 2012: The Letpadaung Copper Mine State Violence 47 The Myitsone Dam 53 CHAPTER 6: Legal Analysis of Land Rights in Burma 57 Land Rights Provided by the Constitution 57 -

16 Commentary on Thailand's Plant Varieties Protection

Copyright Material – Provided by Taylor & Francis 16 Commentary on Thailand’s Plant Varieties Protection Act Gabrielle Gagné and Chutima Ratanasatien The Thai Plant Varieties Protection Act, 1999, (PVPA)1 is a sui generis system that contains three types of protections for plant varieties: (1) intellectual prop- erty protections for new plant varieties that are novel, distinct, uniform and stable; (2) intellectual property protections for local domestic varieties which are distinct, uniform and stable (DUS), but not necessarily novel; and (3) access and benefit sharing–style protections for general domestic plant varieties and wild plant varieties. Interestingly, while wild plant varieties do not have to be uniform, the Act stipulates that they must be stable and distinct.2 Protection of new plant varieties The conditions for protection of new plant varieties is very similar in some respect to those included in the UPOV Convention (International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants) system. In addition to having to be DUS,3 new plant varieties must not have been distributed in or outside the Kingdom by the breeder or with the breeder’s consent for more than one year prior to the date of application. This condition is, of course, roughly equivalent to the concept of commercial novelty included in the UPOV Conventions and many countries’ plant variety protection laws.4 The rights conferred with respect to new plant varieties are also roughly equivalent to those provided for under UPOV 1991,5 although the limits to the scope of protection differ in several manners,6 and the protection periods are shorter7 than those established by UPOV 1991.8 Going beyond the UPOV Conventions, the Thai law requires applications for new plant variety protection to include details about the origin of the genetic material used for breeding,9 as well as a proof of a profit-sharing agree- ment when general domestic or wild plant varieties have been used for breed- ing of the variety.10 Accepted varieties are included in a national register of protected varieties. -

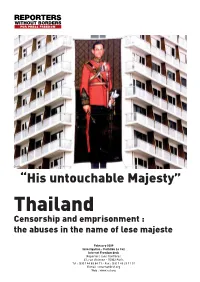

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development.