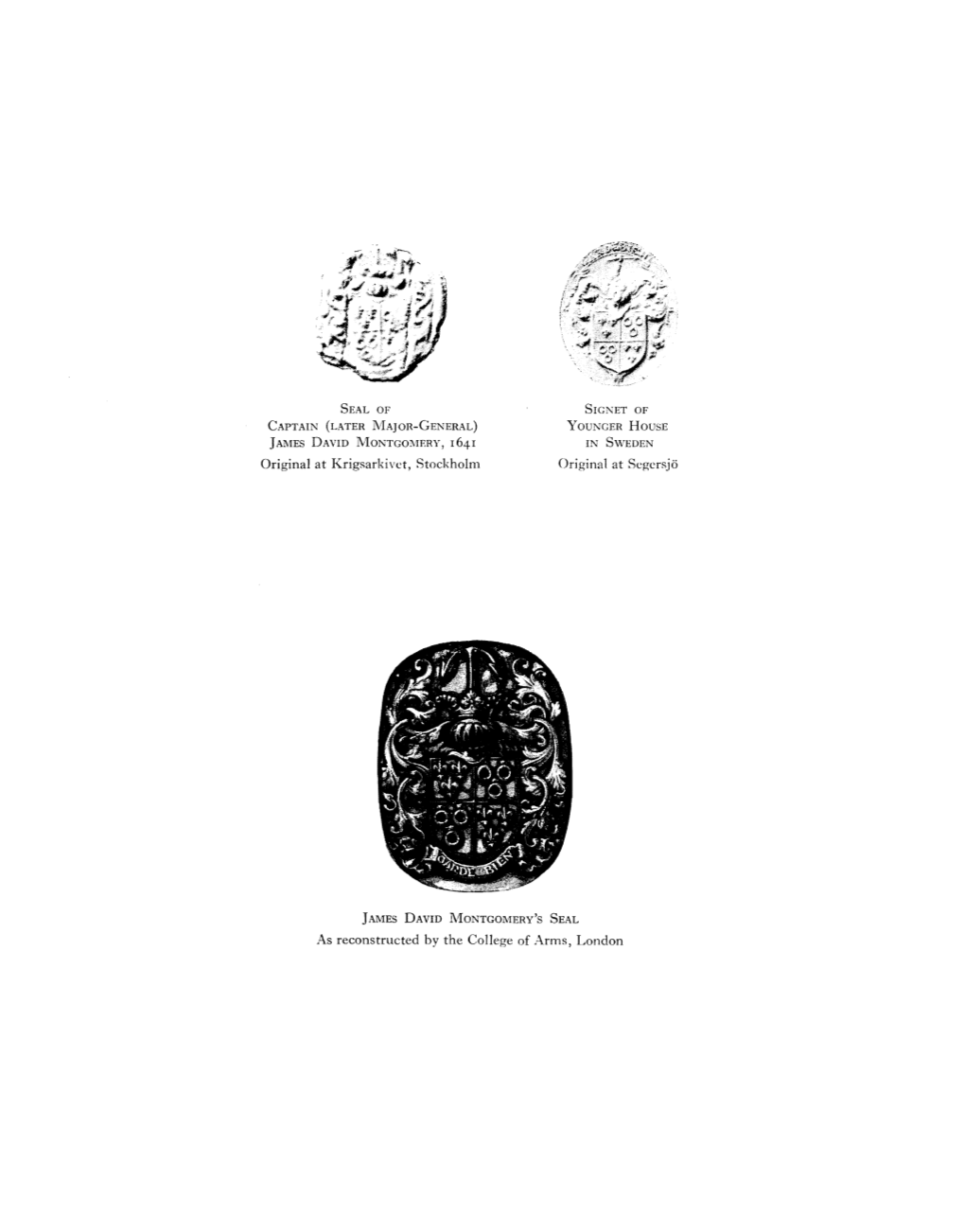

Montgomery's Seal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

The Yellow Star | Teacher's Guide

TEACHER’S GUIDE The Yellow Star: The Legend of King Christian X of Denmark Written by Carmen Agra Deedy Illustrated by Henri Sørensen HC: 978-1-56145-208-8 PB: 978-1-68263-189-8 Ages 8–12 AR • AC • Lexile • F&P • GRL S; Gr 4 ABOUT THE BOOK A NOTE FROM THE PREPARER For centuries, the Star of David was a symbol of Jewish This story of King Christian X’s response to the order pride. But during World War II, Nazis used the star to that Jews in Denmark must wear yellow stars on their segregate and terrorize the Jewish people. Except in clothing is a powerful introduction to the bravery of Denmark. people who resisted the Nazis during World War II. When Nazi soldiers occupied his country, King Students in the middle elementary years are generally Christian X of Denmark committed himself to keeping aware of the Holocaust, but often they know little about all Danes safe from harm. the ways people responded to the terrible things The bravery of the Danes and their king has happening around them. Though the story in this book is inspired many legends. The most enduring is the legend a legend, it illustrates the strength and spirit of a nation of the yellow star, which symbolizes the loyalty and committed to justice for all its people. fearless spirit of the king and his people. Carmen Agra Deedy has recreated this legend with BEFORE YOU READ Danish illustrator Henri Sørensen. Deedy’s lyrical prose To understand the context of this story, students need to and Sørensen’s arresting portraits unite to create a know a bit about World War II in Europe. -

This Copy of the Thesis Has Been Supplied on Condition That Anyone Who

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2014 The British Way of War in North West Europe 1944-45: A Study of Two Infantry Divisions Devine, Louis Paul http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/3014 Plymouth University All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior consent. 1 THE BRITISH WAY OF WAR IN NORTH WEST EUROPE 1944-45: A STUDY OF TWO INFANTRY DIVISIONS By LOUIS PAUL DEVINE A thesis Submitted to Plymouth University in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Humanities May 2013 2 Louis Paul Devine The British Way of War in North West Europe 1944-45: A Study of two infantry divisions Abstract This thesis will examine the British way of war as experienced by two British Infantry Divisions - the 43rd ‘Wessex’ and 53rd ‘Welsh’ - during the Overlord campaign in North West Europe in 1944 and 1945. The main locus of research centres on the fighting components of those divisions; the infantry battalions and their supporting regiments. -

Early Silurian Oceanic Episodes and Events

Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 150, 1993, pp. 501-513, 3 figs. Printed in Northern Ireland Early Silurian oceanic episodes and events R. J. ALDRIDGE l, L. JEPPSSON 2 & K. J. DORNING 3 1Department of Geology, The University, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK 2Department of Historical Geology and Palaeontology, SiSlvegatan 13, S-223 62 Lund, Sweden 3pallab Research, 58 Robertson Road, Sheffield $6 5DX, UK Abstract: Biotic cycles in the early Silurian correlate broadly with postulated sea-level changes, but are better explained by a model that involves episodic changes in oceanic state. Primo episodes were characterized by cool high-latitude climates, cold oceanic bottom waters, and high nutrient supply which supported abundant and diverse planktonic communities. Secundo episodes were characterized by warmer high-latitude climates, salinity-dense oceanic bottom waters, low diversity planktonic communities, and carbonate formation in shallow waters. Extinction events occurred between primo and secundo episodes, with stepwise extinctions of taxa reflecting fluctuating conditions during the transition period. The pattern of turnover shown by conodont faunas, together with sedimentological information and data from other fossil groups, permit the identification of two cycles in the Llandovery to earliest Weniock interval. The episodes and events within these cycles are named: the Spirodden Secundo episode, the Jong Primo episode, the Sandvika event, the Malm#ykalven Secundo episode, the Snipklint Primo episode, and the lreviken event. Oceanic and climatic cyclicity is being increasingly semblages (Johnson et al. 1991b, p. 145). Using this recognized in the geological record, and linked to major and approach, they were able to detect four cycles within the minor sedimentological and biotic fluctuations. -

Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Digging up the Kirkyard: Death, Readership and Nation in the Writings of the Blackwood’s Group 1817-1839. Sarah Sharp PhD in English Literature The University of Edinburgh 2015 2 I certify that this thesis has been composed by me, that the work is entirely my own, and that the work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. Sarah Sharp 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Penny Fielding for her continued support and encouragement throughout this project. I am also grateful for the advice of my secondary supervisor Bob Irvine. I would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Wolfson Foundation for this project. Special thanks are due to my parents, Andrew and Kirsty Sharp, and to my primary sanity–checkers Mohamad Jahanfar and Phoebe Linton. -

The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service

Quidditas Volume 9 Article 9 1988 The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service F. Jeffrey Platt Northern Arizona University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Platt, F. Jeffrey (1988) "The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service," Quidditas: Vol. 9 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol9/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JRMMRA 9 (1988) The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service by F. Jeffrey Platt Northern Arizona University The critical early years of Elizabeth's reign witnessed a watershed in European history. The 1559 Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis, which ended the long Hapsburg-Valois conflict, resulted in a sudden shift in the focus of international politics from Italy to the uncomfortable proximity of the Low Countries. The arrival there, 30 miles from England's coast, in 1567, of thousands of seasoned Spanish troops presented a military and commer cial threat the English queen could not ignore. Moreover, French control of Calais and their growing interest in supplanting the Spanish presence in the Netherlands represented an even greater menace to England's security. Combined with these ominous developments, the Queen's excommunica tion in May 1570 further strengthened the growing anti-English and anti Protestant sentiment of Counter-Reformation Europe. These circumstances, plus the significantly greater resources of France and Spain, defined England, at best, as a middleweight in a world dominated by two heavyweights. -

Download ASF Centennial Ball Press Release

The American-Scandinavian Foundation Celebrates its 100th Anniversary at Centennial Ball Royalty from Sweden, Norway, and Denmark and Presidents of Finland and Iceland were Guests of Honor at this milestone event New York, NY (October 25, 2011) - Amid the pomp and circumstance of a historic evening, Nordic-American friendship was on full display as Scandinavian Heads of State, European royalty, top diplomats, and distinguished members of the U.S. and Nordic cultural, educational, business, and philanthropic communities celebrated the 100th Anniversary of The American-Scandinavian Foundation at its Centennial Ball in New York City. Some 1,200 guests attended the black-tie affair in recognition of the ASF's 100 years of building cultural and educational bridges between the United States and the Nordic countries of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. Special Guests of Honor were: Their Majesties King Carl XVI Gustaf and Queen Silvia of Sweden; Their Majesties King Harald V and Queen Sonja of Norway; His Excellency Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, President of Iceland, and Mrs. Dorrit Moussaieff; Her Excellency Tarja Halonen, President of Finland; and Their Royal Highnesses Crown Prince Frederik and Crown Princess Mary of Denmark. “The Centennial Ball offered us an opportunity to reflect on the 100-year history and achievements of our unique organization and to celebrate the mutual respect and understanding between the United States and Nordic countries,” said Edward P. Gallagher, President of The American-Scandinavian Foundation. “We were -

Parish of Skipton*

294 HISTORY OF CRAVEN. PARISH OF SKIPTON* HAVE reserved for this parish, the most interesting part of my subject, a place in Wharfdale, in order to deduce the honour and fee of Skipton from Bolton, to which it originally belonged. In the later Saxon times Bodeltone, or Botltunef (the town of the principal mansion), was the property of Earl Edwin, whose large possessions in the North were among the last estates in the kingdom which, after the Conquest, were permitted to remain in the hands of their former owners. This nobleman was son of Leofwine, and brother of Leofric, Earls of Mercia.J It is somewhat remarkable that after the forfeiture the posterity of this family, in the second generation, became possessed of these estates again by the marriage of William de Meschines with Cecilia de Romille. This will be proved by the following table:— •——————————;——————————iLeofwine Earl of Mercia§=j=......... Leofric §=Godiva Norman. Edwin, the Edwinus Comes of Ermenilda=Ricardus de Abrineis cognom. Domesday. Goz. I———— Matilda=.. —————— I Ranulph de Meschines, Earl of Chester, William de Meschines=Cecilia, daughter and heir of Robert Romille, ob. 1129. Lord of Skipton. But it was before the Domesday Survey that this nobleman had incurred the forfeiture; and his lands in Craven are accordingly surveyed under the head of TERRA REGIS. All these, consisting of LXXVII carucates, lay waste, having never recovered from the Danish ravages. Of these-— [* The parish is situated partly in the wapontake of Staincliffe and partly in Claro, and comprises the townships of Skipton, Barden, Beamsley, Bolton Abbey, Draughton, Embsay-with-Eastby, Haltoneast-with-Bolton, and Hazlewood- with-Storithes ; and contains an area of 24,7893. -

Beowulf and the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial

Beowulf and The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial The value of Beowulf as a window on Iron Age society in the North Atlantic was dramatically confirmed by the discovery of the Sutton Hoo ship-burial in 1939. Ne hÿrde ic cymlīcor cēol gegyrwan This is identified as the tomb of Raedwold, the Christian King of Anglia who died in hilde-wæpnum ond heaðo-wædum, 475 a.d. – about the time when it is thought that Beowulf was composed. The billum ond byrnum; [...] discovery of so much martial equipment and so many personal adornments I never yet heard of a comelier ship proved that Anglo-Saxon society was much more complex and advanced than better supplied with battle-weapons, previously imagined. Clearly its leaders had considerable wealth at their disposal – body-armour, swords and spears … both economic and cultural. And don’t you just love his natty little moustache? xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx(Beowulf, ll.38-40.) Beowulf at the movies - 2007 Part of the treasure discovered in a ship-burial of c.500 at Sutton Hoo in East Anglia – excavated in 1939. th The Sutton Hoo ship and a modern reconstruction Ornate 5 -century head-casque of King Raedwold of Anglia Caedmon’s Creation Hymn (c.658-680 a.d.) Caedmon’s poem was transcribed in Latin by the Venerable Bede in his Ecclesiatical History of the English People, the chief prose work of the age of King Alfred and completed in 731, Bede relates that Caedmon was an illiterate shepherd who composed his hymns after he received a command to do so from a mysterious ‘man’ (or angel) who appeared to him in his sleep. -

Mary Queen of Scots a Narravtive and Defence

MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS THE ABERDEEN UNIVERSITY PRESS : JOHN THOMSOtf AND J. F. THOMSON, M.A. M a\ V e.>r , r\ I QUEEN OF SCOTS A NARRATIVE AND DEFENCE WITH PORTRAIT AND EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS SPECIALLY DRAWN FOR THE WORK ABERDEEN THE UNIVERSITY PRESS I 889r 3,' TO THE MEMORY OF MARY MARTYR QUEEN OF SCOTS THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE ebtcdfeb A PURE WOMAN, A FAITHFUL WIFE, A SOVEREIGN ENLIGHTENED BEYOND THE TUTORS OF HER AGE FOREWORD. effort is made in the few following AN pages to condense the reading of many years, and the conclusion drawn from almost all that has been written in defence and in defame of Mary Stuart. Long ago the world was at one as to the character of the Casket Letters. To these forgeries the writer thinks there must now be added that document discovered in the Charter Room of Dunrobin Castle by Dr. John Stuart. In that most important and deeply interesting find, recently made in a loft above the princely stables of Belvoir Castle, in a letter from Randolph to Rutland, of loth June, 1563, these words occur in writing about our Queen : "She is the fynneste she that ever was ". This deliberately expressed opinion of Thomas Randolph will, I hope, be the opinion of my readers. viii Foreword. The Author has neither loaded his page with long footnote extracts, nor enlarged his volume with ponderous glossarial or other appendices. To the pencil of Mr. J. G. Murray of Aber- deen, and the etching needle of M. Vaucanu of Paris, the little book is much beholden. -

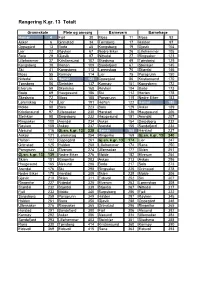

Rangering K.Gr. 13 Totalt

Rangering K.gr. 13 Totalt Grunnskole Pleie og omsorg Barnevern Barnehage Hamar 4 Fjell 30 Moss 11 Moss 92 Asker 6 Grimstad 34 Tønsberg 17 Halden 97 Oppegård 13 Bodø 45 Kongsberg 19 Gjøvik 104 Lier 22 Røyken 67 Nedre Eiker 26 Lillehammer 105 Sola 29 Gjøvik 97 Nittedal 27 Ringsaker 123 Lillehammer 37 Kristiansund 107 Skedsmo 49 Tønsberg 129 Kongsberg 38 Horten 109 Sandefjord 67 Steinkjer 145 Ski 41 Kongsberg 113 Lørenskog 70 Stjørdal 146 Moss 55 Karmøy 114 Lier 75 Porsgrunn 150 Nittedal 55 Hamar 123 Oppegård 86 Kristiansund 170 Tønsberg 56 Steinkjer 137 Karmøy 101 Kongsberg 172 Elverum 59 Skedsmo 168 Røyken 104 Bodø 173 Bodø 69 Haugesund 186 Ski 112 Horten 178 Skedsmo 72 Moss 188 Porsgrunn 115 Nedre Eiker 183 Lørenskog 74 Lier 191 Horten 122 Hamar 185 Molde 88 Sola 223 Sola 129 Asker 189 Kristiansund 97 Ullensaker 230 Harstad 136 Haugesund 206 Steinkjer 98 Sarpsborg 232 Haugesund 151 Arendal 207 Ringsaker 100 Arendal 234 Asker 154 Sarpsborg 232 Røyken 108 Askøy 237 Arendal 155 Sandefjord 234 Ålesund 116 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 238 Hamar 168 Harstad 237 Askøy 121 Lørenskog 254 Ringerike 169 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 240 Horten 122 Oppegård 261 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 174 Lier 247 Grimstad 125 Halden 268 Lillehammer 174 Rana 250 Porsgrunn 133 Elverum 274 Ullensaker 177 Skien 251 Gj.sn. k.gr. 13 139 Nedre Eiker 276 Molde 182 Elverum 254 Skien 151 Ringerike 283 Askøy 213 Askøy 256 Haugesund 165 Ålesund 288 Bodø 217 Sola 273 Arendal 176 Ski 298 Ringsaker 225 Grimstad 278 Nedre Eiker 179 Harstad 309 Skien 239 Molde 306 Gjøvik 210 Skien 311 Eidsvoll 252 Ski 307 Ringerike -

THE LONDON Gfaz^TTE, JULY 5, 1904. 4237

THE LONDON GfAZ^TTE, JULY 5, 1904. 4237 ; '.' "• Y . ' '-Downing,Street. Charles, Earl of-Leitrim. '-'--•'. ' •' July 5, 1904. jreorge, Earl of Lucan. The KING has been pleased to approve of the Somerset Richard, Earl of Belmore. appointment of Hilgrpye Clement Nicolle, Esq. Tames Francis, Earl of Bandon. (Local Auditor, Hong Kong), to be Treasurer of Henry James, Earl Castle Stewart. the Island of Ceylon. Richard Walter John, Earl of Donoughmore. Valentine Augustus, Earl of Kenmare. • William Henry Edmond de Vere Sheaffe, 'Earl of Limericks : i William Frederick, Earl-of Claricarty. ''" ' Archibald Brabazon'Sparrow/Earl of Gosford. Lawrence, Earl of Rosse. '• -' • . ELECTION <OF A REPRESENTATIVE PEER Sidney James Ellis, Earl of Normanton. FOR IRELAND. - Henry North, -Earl of Sheffield. Francis Charles, Earl of Kilmorey. Crown and Hanaper Office, Windham Thomas, Earl of Dunraven and Mount- '1st July, 1904. Earl. In pursuance of an Act passed in the fortieth William, Earl of Listowel. year of the reign of His Majesty King George William Brabazon Lindesay, Earl of Norbury. the Third, entitled " An Act to regulate the mode Uchtef John Mark, Earl- of Ranfurly. " by which the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Jenico William Joseph, Viscount Gormanston. " the Commons, to serve ia the Parliament of the Henry Edmund, Viscount Mountgarret. " United Kingdom, on the part of Ireland, shall be Victor Albert George, Viscount Grandison. n summoned and returned to the said Parliament," Harold Arthur, Viscount Dillon. I do hereby-give Notice, that Writs bearing teste Aldred Frederick George Beresford, Viscount this day, have issued for electing a Temporal Peer Lumley. of Ireland, to succeed to the vacancy made by the James Alfred, Viscount Charlemont.