Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scottish Water: Glencorse WTW E:Letter 18

Scottish Water: Glencorse WTW E:letter 19 Introduction It has been three months since the previous e:letter, in this intervening time the Glencorse project has made steady progress through the 2009 winter. At an elevation of approximately 650 feet above sea level, the weather by Penicuik this winter has been very fresh at times and also white with snow! Nonetheless, the landscape at Glencorse has been transformed by the construction work currently taking place. The project is highly visible from the surrounding area by the large tower cranes that are now visible above the skyline. Regular progress has been captured with photographs updated monthly on our project website (www.scottishwater.co.uk/glencorse). Work on the ground Significant progress has been made in constructing the Glencorse Water Treatment Works building. As of this week, we have started construction of our Clear Water Tank (treated water storage reservoir). This begins with a large earth moving phase whereby we will be digging a hole to accommodate the large concrete tank, which will then be buried after construction. A summary of some of our recent work at Glencorse is below: Completed Works Water mains diversions by the A702 completed as planned. Remaining overhead power lines at Glencorse removed as planned. Site offices and welfare units for workforce fully established. Tower cranes erected. Water Treatment Works (WTW) excavation completed. Civil construction (concrete) of WTW foundations complete. Ongoing/Planned Works Civil construction of WTW walls, tanks and channels Excavation of Clear Water Tank commences Export of excess subsoil commences Civil construction of foundations for Clear Water Tank to commence in early summer. -

![Covering Colinton, Longstone & Slateford]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3961/covering-colinton-longstone-slateford-53961.webp)

Covering Colinton, Longstone & Slateford]

Edinburgh’s Great War Roll of Honour Colinton District Great War Roll of Honour: Restricted [Covering Colinton, Longstone & Slateford] This portion of the Edinburgh Great War Roll of Honour is part of a much larger work that will be published over a period of time. It should also be noted that this particular roll is also a restricted one of Great War casualties giving basic details of each casualty: Name, Rank, Battalion/Ship/Squadron, Regiment/Service, Number. Special awards. Cause and date of death. Age. Place commemorated or buried. Birthplace. District of Edinburgh’s Great War Roll of Honour name is recorded in. The reason this roll is presently restricted is that we would like to invite and give the greater community the opportunity to fill out the story of each casualty, even helping identify casualties that appear on local memorials that cannot be clearly identified or have some details missing. These latter casualties appear in red with some having question marks in the area that needs to be clarified. It is also worth noting at this point that the names of some casualties appear on more than one district. The larger Roll of Honour [RoH] will also include information about those who served and survived and again the hope is that the wider community will come forward and share the story of their ancestors’ who served in the Great War, whether a casualty or survivor. The larger RoH will contain information such as: Name. Rank, Battalion/Ship/Squadron, Regiment/Service. Born when and where? Parent’s names and address. -

List of the Old Parish Registers of Scotland 758-811

List of the Old Parish Registers Midlothian (Edinburgh) OPR MIDLOTHIAN (EDINBURGH) 674. BORTHWICK 674/1 B 1706-58 M 1700-49 D - 674/2 B 1759-1819 M 1758-1819 D 1784-1820 674/3 B 1819-54 M 1820-54 D 1820-54 675. CARRINGTON (or Primrose) 675/1 B 1653-1819 M - D - 675/2 B - M 1653-1819 D 1698-1815 675/3 B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D 1793-1854 676. COCKPEN* 676/1 B 1690-1783 M - D - 676/2 B 1783-1819 M 1747-1819 D 1747-1813 676/3 B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D 1832-54 RNE * See Appendix 1 under reference CH2/452 677. COLINTON (or Hailes) 677/1 B 1645-1738 M - D - 677/2 B 1738-1819* M - D - 677/3 B - M 1654-1819 D 1716-1819 677/4 B 1815-25* M 1815-25 D 1815-25 677/5 B 1820-54*‡ M 1820-54 D - 677/6 B - M - D 1819-54† RNE 677/7 * Separate index to B 1738-1851 677/8 † Separate index to D 1826-54 ‡ Contains index to B 1852-54 Surname followed by forename of child 678. CORSTORPHINE 678/1 B 1634-1718 M 1665-1718 D - 678/2 B 1709-1819 M - D - 678/3 B - M 1709-1819 D 1710-1819 678/4 B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D 1820-54 List of the Old Parish Registers Midlothian (Edinburgh) OPR 679. CRAMOND 679/1 B 1651-1719 M - D - 679/2 B 1719-71 M - D - 679/3 B 1771-1819 M - D - 679/4 B - M 1651-1819 D 1816-19 679/5 B 1819-54 M 1819-54 D 1819-54* * See library reference MT011.001 for index to D 1819-54 680. -

Introduction: Borderlines: Contemporary Scottish Gothic

Notes Introduction: Borderlines: Contemporary Scottish Gothic 1. Caroline McCracken-Flesher, writing shortly before the latter film’s release, argues that it is, like the former, ‘still an outsider tale’; despite the emphasis on ‘Scottishness’ within these films, they could only emerge from outside Scotland. Caroline McCracken-Flesher (2012) The Doctor Dissected: A Cultural Autopsy of the Burke and Hare Murders (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 20. 2. Kirsty A. MacDonald (2009) ‘Scottish Gothic: Towards a Definition’, The Bottle Imp, 6, 1–2, p. 1. 3. Andrew Payne and Mark Lewis (1989) ‘The Ghost Dance: An Interview with Jacques Derrida’, Public, 2, 60–73, p. 61. 4. Nicholas Royle (2003) The Uncanny (Manchester: Manchester University Press), p. 12. 5. Allan Massie (1992) The Hanging Tree (London: Mandarin), p. 61. 6. See Luke Gibbons (2004) Gaelic Gothic: Race, Colonization, and Irish Culture (Galway: Arlen House), p. 20. As Coral Ann Howells argues in a discussion of Radcliffe, Mrs Kelly, Horsley-Curteis, Francis Lathom, and Jane Porter, Scott’s novels ‘were enthusiastically received by a reading public who had become accustomed by a long literary tradition to associate Scotland with mystery and adventure’. Coral Ann Howells (1978) Love, Mystery, and Misery: Feeling in Gothic Fiction (London: Athlone Press), p. 19. 7. Ann Radcliffe (1995) The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne, ed. Alison Milbank (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p. 3. 8. As James Watt notes, however, Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne remains a ‘derivative and virtually unnoticed experiment’, heavily indebted to Clara Reeves’s The Old English Baron. James Watt (1999) Contesting the Gothic: Fiction, Genre and Cultural Conflict, 1764–1832 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), p. -

LASSWADE HIGH SCHOOL GROUPS/CLUBS INFORMATION Thursday 13Th September 2018 Assemblies Topic:Extra Curriculam

LASSWADE HIGH SCHOOL GROUPS/CLUBS INFORMATION Thursday 13th September 2018 Assemblies Topic:Extra Curriculam Thursday 13th September S4 – 8.30 – 8.40 Friday 14th September S5/S6 - 8.30 -8.40 All students who did not receive their certificate at the Senior Prize Giving Ceremony please see Mrs Hughes in the Deputy Head office to collect their certificates LEAPS STUDENTS If you have not already done so, please complete the online survey to secure an interview. If you have any difficulties with this please see Mrs Costello in Room 111. Would all S6s attending prom please pay a £10 deposit by Friday 14th September to secure our place at the Balmoral 7th June. Please give your money to Marnie, Hannah F or Wojtek. Any issues regarding money please speak to Miss Whittingham in room 215. WWI BATTLEFIELDS TRIP June 2019 There are still some spaces left on the Battlefields trip. If you would like to go please collect a letter from Miss Blake or Miss Whittingham. Deposits are due by 28th September. S4 (Last years Bronze group) The following students need to see Mr Boyle in Room 105 on Monday 17th September at 1.30pm: Holli Boyd Emily Carson Abbie McIntyre Abbie Malinowski Holly Swift Kira Urquahart-Smith S3 Bronze Duke of Edinburgh’s Award Students interested in working towards this award should collect an application form from Mr Boyle in Room 105. Deadline for returning completed forms is morning break, Friday 21st September. Late applications will not be considered. S3-S5 London trip June 2019 • Important information: The dates have changed to: Monday 17th to Thursday 20th June 2019 • If this means you can no longer attend, you MUST tell Miss Conlan (room 118) by Friday 14th Sept. -

Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott's Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I Conscious of Any Thing Peculiar in My Own Moral

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Mary's University Open Research Archive Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott’s Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I conscious of any thing peculiar in my own moral character which could render such development [a moral lesson] necessary or useful, I would as readily consent to it as I would bequeath my body to dissection if the operation could tend to point out the nature and the means of curing any peculiar malady.1 This essay considers conflicts of corporeality in Walter Scott’s works, critical reception, and cultural status, drawing on recent scholarship on the physical in the Romantic Period and on considerations of disability in modern and contemporary poetics. Although Scott scholarship has said little about the significance of disability as something reconfigured – or ‘disfigured’ – in his writings, there is an increasing interest in the importance of the body in Scott’s work. This essay offers new directions in interpretation and scholarship by opening up several distinct, though interrelated, aspects of the corporeal in Scott. It seeks to demonstrate how many areas of Scott’s writing – in poetry and prose, and in autobiography – and of Scott’s critical and cultural standing, from Lockhart’s biography to the custodianship of his library at Abbotsford, bear testimony to a legacy of disfigurement and substitution. In the ‘Memoirs’ he began at Ashestiel in April 1808, Scott described himself as having been, in late adolescence, ‘rather disfigured than disabled’ by his lameness.2 Begun at his rented house near Galashiels when he was 36, in the year in which he published his recursive poem Marmion and extended his already considerable fame as a poet, the Ashestiel ‘Memoirs’ were continued in 1810-11 (that is, still before the move to Abbotsford), were revised and augmented in 1826, and ten years later were made public as the first chapter of John Gibson Lockhart’s Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. -

Bissonette on Rosner, 'The Anatomy Murders: Being The

H-Law Bissonette on Rosner, 'The Anatomy Murders: Being the True and Spectacular History of Edinburgh's Notorious Burke and Hare and of the Man of Science Who Abetted Them in the Commission of Their Most Heinous Crimes' Review published on Friday, January 28, 2011 Lisa Rosner. The Anatomy Murders: Being the True and Spectacular History of Edinburgh's Notorious Burke and Hare and of the Man of Science Who Abetted Them in the Commission of Their Most Heinous Crimes. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010. vi + 328 pp. $29.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8122-4191-4. Reviewed by Melissa Bissonette (St. John Fisher College)Published on H-Law (January, 2011) Commissioned by Christopher R. Waldrep The Creepy and Bloodless Crime Spree: Science and Murder in Edinburgh In 1818, Mary Shelley wrote of Victor Frankenstein, a man of pure reason, becoming a star pupil in the study of natural philosophy and physiology. She has her hero bluntly acknowledge that “to examine the causes of life, we must first have recourse to death,” which is found only in “vaults and charnel houses” and amid the “unhallowed damps of the grave” (pp. 79, 82). Though without “superstition” himself, Victor is fully aware of the popular prejudice against the use of corpses; he works at night and in secret. Thus Shelley articulated what was an awkward yoking of knowledge and fear, humanity’s advance and its criminal underbelly, throughout the Enlightenment. Lisa Rosner’s The Anatomy Murders explores that yoking as exemplified by William Burke and William Hare, serial killers of 1828, whose string of murders were motivated by the constant demand, from the schools of anatomy and surgery in Edinburgh, for bodies to study. -

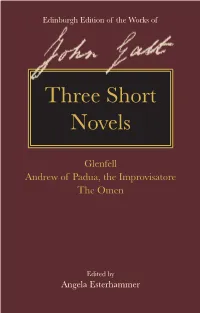

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

Proquest Dissertations

RICE UNIVERSITY Material Fictions: Readers and Textuality in the British Novel, 1814-1852 by Duncan Ingraham Haseli A THESIS SUBMITTED EM PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy AppRavæD, THESIS CPMMITTEE: Robert L. Patten, Lynette S. Autrey Professor in the Humanities, Director Helena Michie, Agnes Cullen Arnold Professor in the Humanities, Professor of and Chair, English Martin Wiener, Mary Gibbs Jones Professor, History HOUSTON, TEXAS JANUARY 2009 UMI Number: 3362239 Copyright 2009 by Hasell, Duncan Ingraham INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform 3362239 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 AnnArbor, Ml 48106-1346 Copyright Duncan Ingraham Hasell 2009 ABSTRACT Material Fictions: Readers and Textuality in the British Novel, 1814-1852 by Duncan Ingraham Hasell I argue in the first chapter that the British novel's material textuality, that is the physical features of the texts that carry semantic weight and the multiple forms in which texts are created and distributed, often challenges and subverts present conceptions of the cultural roles of the novel in the nineteenth century. -

Walter Scott: a Legend of Montrose ======A Machine-Readable Edition

Walter Scott: A Legend of Montrose ================================== a machine-readable edition version 1.1: 1995-09-14 ------------------------------------------------------------ <titlepage> A LEGEND OF MONTROSE BY SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART <series title> THE TALES OF MY LANDLORD A LEGEND OF MONTROSE <series epigraph> Hear, Land o' Cakes and brither Scots, From Maidenkirk to Johnny Groats, If there's a hole in a' your coats, I rede ye tent it; A chiel's amang you takin' notes, An' faith he'll prent it!---Burns Ahora bien, dijo el Cura; traedme, senor hu<e'>sped, aquesos libros, que los quiero ver. Que me place, respondi<o'> el; y entrando en su aposent, sac<o'> d<e'>l una maletilla vieja cerrada con una cadenilla, y abri<e'>ndola, hall<o'> en ella tres libros grandes y unos papeles de muy buena letra escritos de mano.---=Don Quixote,= Parte I. capitulo 32. <text> INTRODUCTION TO THE FIRST EDITION. Sergeant More M`Alpin was, during his residence among us, one of the most honoured inhabitants of Gandercleugh. No one thought of disputing his title to the great leathern chair on the ``cosiest side of the chimney,'' in the common room of the Wallace Arms, on a Saturday evening. No less would our sexton, John Duirward, have held it an unlicensed intrusion, to suffer any one to induct himself into the corner of the left-hand pew nearest to the pulpit, which the Sergeant regularly occupied on Sundays. There he sat, his blue invalid uniform brushed with the most scrupulous accuracy. Two medals of merit displayed at his buttonhole, as well as the empty sleeve which should have been occupied by his right arm, bore evidence of his hard and honourable service. -

Margaret Oliphant: Gender, Identity, and Value in the Victonan Penodical Press

University of Alberta Margaret Oliphant: Gender, Identity, and Value in the Victonan Penodical Press Rhonda-Lea Carson-Batchelor O A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Shidies and Research in partial fulfillrnent of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of English Edmonton, Alberta Fa11, 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 ,mada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Senrices services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, ~e Weilington OttawaON KIAW Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Biblothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, Loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform., vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/lfilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract The Victorian penod saw the rise of many women to professiond eminence in literary fields. Margaret Oliphant (1 828- l897), novelist, biographer, literary critic, social commentator, and historian, was just one who participated in the cultural debate about the changing place, role, and value of women within society and the workplace--'the woman questiony--buther conservative and careful feminism has attracted linle critical attention (or esteem) to her fiction. -

Obituary You Cannot Take Your Own When Travelling in a Strange Car

BRITISH AUG. 27, 1960 CORRESPONDENCE MEDICAL JOURNAL 671 and hats for themselves and for members of their fami- lies. I have bought five. One last point. As yet few cars have safety belts and Obituary you cannot take your own when travelling in a strange car. You can take your hat.-I am, etc., LORD HADEN-GUEST, M.C., M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P. The Institute of Orthopaedics, H. J. SEDDON, London, W.1. President, British Orthopaedic Lord Haden-Guest, who was a medical officer to one Association. of the earliest child-welfare clinics in London and then REFERENCE became a well-known Labour politician, died on Gissane, W., Brit. med. J., 1959, 1, 235. August 20. He was 83 years of age. Leslie Haden Guest was born at Oldham, Lancashire, on Cat Phobia March 10, 1877, the son of Dr. Alexander Haden Guest, SIR,-In your issue of August 13 (p. 497), writing of a who practised in Manchester and had many friends among case of cat phobia treated by them, Dr. H. L. Freeman the Fabians and radical thinkers of his day. Educated at and Mr. D. C. Kendrick are guilty of an inaccuracy William Hulme's Grammar School and at Owens College, sufficiently gross to merit correction on my part. In Manchester, Leslie Haden Guest continued his medical training at the London Hos- their brief and pejorative survey of the results of pital, qualifying M.R.C.S., psychotherapy of mental disorders, they say, inter alia: L.R.C.P. in 1900. After " Glover (1955) has disavowed any claims for the thera- serving as a civil surgeon in peutic usefulness of psycho-analytic methods." I the South African war he gather from their list of references that the disavowal remained in South Africa was made in my textbook The Technique of Psycho- for a time and then returned analysis.