Acute Bacterial Meningitis Sharon E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cerebrospinal Fluid in Critical Illness

Cerebrospinal Fluid in Critical Illness B. VENKATESH, P. SCOTT, M. ZIEGENFUSS Intensive Care Facility, Division of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, Royal Brisbane Hospital, Brisbane, QUEENSLAND ABSTRACT Objective: To detail the physiology, pathophysiology and recent advances in diagnostic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in critical illness, and briefly review the pharmacokinetics and pharmaco- dynamics of drugs in the CSF when administered by the intravenous and intrathecal route. Data Sources: A review of articles published in peer reviewed journals from 1966 to 1999 and identified through a MEDLINE search on the cerebrospinal fluid. Summary of review: The examination of the CSF has become an integral part of the assessment of the critically ill neurological or neurosurgical patient. Its greatest value lies in the evaluation of meningitis. Recent publications describe the availability of new laboratory tests on the CSF in addition to the conventional cell count, protein sugar and microbiology studies. Whilst these additional tests have improved our understanding of the pathophysiology of the critically ill neurological/neurosurgical patient, they have a limited role in providing diagnostic or prognostic information. The literature pertaining to the use of these tests is reviewed together with a description of the alterations in CSF in critical illness. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs in the CSF, when administered by the intravenous and the intrathecal route, are also reviewed. Conclusions: The diagnostic utility of CSF investigation in critical illness is currently limited to the diagnosis of an infectious process. Studies that have demonstrated some usefulness of CSF analysis in predicting outcome in critical illness have not been able to show their superiority to conventional clinical examination. -

CSF Xanthochromia

CSF Xanthochromia Pseudonyms – CSF bilirubin For investigation of suspected subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) in CT negative patients Xanthochromia is the yellow discoloration indicating the presence of bilirubin in CSF which appears as oxyhaemoglobin released from the breakdown of red blood cells following haemorrhage into the CSF is converted in vivo into bilirubin in a time‐dependent manner. A subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is a spontaneous arterial bleeding into the subarachnoid space, usually from a cerebral aneurysm, and characterised by a severe sudden‐onset headache. The majority of positive cases are detected by computed tomography (CT) scanning but for those CT‐ negative patients presenting with a history suggestive of SAH the measurement of xanthochromia in CSF is advocated to detect those patients who actually have sustained a SAH and require treatment and to eliminate the possibility of SAH in the remainder without the need of confirmatory angiography. The CSF is collected by means of lumbar puncture (LP). For full interpretation of the result other CSF and blood tests must be collected at the same time – CSF protein and glucose; plasma glucose; and serum protein and bilirubin. General information CSF Xanthochromia sample collection kits are provided in the ACU (ORC) and AMU (Trafford) and also available from the Specimen Receptions at the laboratories at both sites. Concurrent samples should be requested for CSF protein and glucose, plasma glucose and serum LFTS (for protein and bilirubin) using the sample containers supplied. Collection container: CSF xanthochromia: White topped Universal container (In addition the following samples should be collected:‐ CSF glucose & protein: 1.2 mL fluoride‐EDTA glucose (Sarstedt yellow top) Serum protein & bilirubin: 4.9 mL SST (Sarstedt brown top) Plasma glucose: 2.7 mL fluoride‐EDTA glucose (Sarstedt yellow top) Type and volume of sample: 1 mL CSF requested, minimum 400 µL required for analysis Specimen transport/special precautions: A CSF Xanthochromia sample collection kit should be used. -

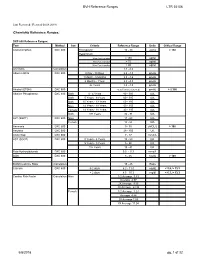

BVH Reference Ranges LTR 35106 Chemistry Reference Ranges

BVH Reference Ranges LTR 35106 Last Reviewed: (Revised 05.08.2018) Chemistry Reference Ranges: DXC 600 Reference Ranges: Test Method Sex Criteria Reference Range Units Critical Range Acetaminophen DXC 600 Therapeutic 10 - 30 ug/mL > 150 Hepatotoxic 4 hrs Post Ingestion > 150 ug/ml 8 hrs Post Ingestion > 75 ug/ml 12 hrs Post Ingestion > 40 ug/ml A/G Ratio Calculation 1.1 - 2.2 Albumin BCG DXC 600 0 Day - 30 Days 2.6 - 4.3 gm/dL 1 Month - 5 Months 2.8 - 4.6 gm/dL 6 Months - 1Year 2.8 - 4.8 gm/dL 2+ Years 3.2 - 4.9 gm/dL Alcohol (ETOH) DXC 600 <0.005 (none detected) gm/dL > 0.300 Alkaline Phosphatase DXC 600 Both 0 - 4 Years 80 - 350 IU/L Both 5 Years - 9 Years 60 - 385 IU/L Both 10 Years - 13 Years 60 - 485 IU/L Male 14 Years - 18 Years 50 - 350 IU/L Female 14 Years - 18 Years 40 - 195 IU/L Both 19+ Years 32 - 91 IU/L ALT (SGPT) DXC 600 Male 17 - 63 IU/L Female 14 - 54 IU/L Ammonia DXC 600 9 - 35 uMOL/L > 100 Amylase DXC 600 28 - 100 U/L Anion Gap DXC 600 7 - 17 mmol/L AST (SGOT) DXC 600 0 Years - 4 Years 10 - 60 IU/L 5 Years - 9 Years 5 - 50 IU/L 10+ Years 15 - 41 IU/L Beta Hydroxybutyrate DXC 600 0.0 - 0.3 mmol/L BUN DXC 600 8 - 26 mg/dL > 100 BUN/Creatinine Ratio Calculation 15 - 25 Ratio Calcium DXC 600 0-2 days 6.2 - 11.0 mg/dL < 5.8, > 13.3 > 2 days 8.5 - 10.3 mg/dl < 6.3, > 13.3 Cardiac Risk Factor Calculation Male 1/2 Average 3.43 Average 4.97 2X Average 9.55 3X Average 23.99 Female 1/2 Average 3.27 Average 4.44 2X Average 7.05 3X Average 11.04 5/8/2018 pg. -

Routine Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis

CHAPTER4 Routine cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis a b a ) F. Deisenhammer, A. Bartos, R. Egg, Albumin CSF/serum ratio (Qalb should be pre- N. E. Gilhus,c G. Giovannoni,d S. Rauer,e ferred to total protein measurement and normal F. Sellebjergf upper limits should be related to patients’ age. Elevated Qalb is a non-specific finding but occurs mainly in bacterial, cryptococcal, and tubercu- Background A great variety of neurological diseases lous meningitis, leptomingeal metastases as well require investigation of the cerebrospinal fluid as acute and chronic demyelinating polyneu- (CSF) to prove the diagnosis or to rule out relevant ropathies. differential diagnoses. Pathological decrease of the CSF/serum glu- cose ratio or an increase in lactate concentration Objectives To evaluate the theoretical background indicates bacterial or fungal meningitis or lep- and provide guidelines for clinical use in rou- tomeningeal metastases. tine CSF analysis including total protein, albumin, Intrathecal immunoglobulin G synthesis is best immunoglobulins, glucose, lactate, cell count, demonstrated by isoelectric focusing followed by cytological staining, and investigation of infec- specific staining. tious CSF. Cellular morphology (cytological staining) should be evaluated whenever pleocytosis is found or Methods Systematic Medline search for the above leptomeningeal metastases or pathological bleed- mentioned variables. Review of appropriate publi- ing is suspected. Computed tomography-negative cations by one or more of the task force members. intrathecal bleeding should be investigated by Grading of evidence and recommendations was bilirubin detection. based on consensus by all task force members. Introduction CSF should be analysed immediately after collec- tion. If storage is needed 12 ml of CSF should The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a dynamic, be partitioned into three to four sterile tubes. -

D40. Cerebrospinal Fluid.Pdf

CEREBROSPINAL FLUID D40 (1) Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Last updated: June 3, 2019 PHYSIOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................ 1 CSF PRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 CSF REABSORPTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 PARAMETERS ........................................................................................................................................... 2 NORMAL ................................................................................................................................................ 2 OPENING PRESSURE ................................................................................................................................ 3 COLOR ................................................................................................................................................... 3 BLOODY CSF ......................................................................................................................................... 3 VISCOSITY & TURBIDITY ....................................................................................................................... 4 CELLS ................................................................................................................................................... -

2017 LAB GUIDE TEST MENU March 2017Edition

2017 LAB GUIDE TEST MENU March 2017Edition Replaces: Sept 2015 Edition STAT TESTING MENU (2 Pages) 30 Minute In-Lab Turnaround Time (TAT) Unless Further Noted Below (In-Lab Time) MICROBIOLOGY 1. Spinal Fluid Culture set up and Gram Stain of sediment, India Ink prep 2. Gram Stain, other sites 3. Planting of cultures 4. Wet prep 5. Rapid Strep A Antigen Test (15 min. TAT) 6. Rapid Influenza A & B Antigen test 7. Rapid RSV Antigen test 8. Malaria Prep (60 min. TAT), Evening and Night shifts will only report “Parasites present or absent” 9. Screen, Gastric Urease, for Helicobacter Pylori (60 min. TAT) 10. Clostridium difficile DNA amplification (60 min. TAT) BLOOD BANK 1. Compatibility testing (leuko-reduced packed cells) 2. Type and Screen (60 min. TAT) 3. Cord Blood (2 hours) HEMATOLOGY 1. Complete Blood Count (CBC) SEE NOTE #1 2. Fibrinogen 3. Hemogram (ABC) 4. Monospot Test 5. Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT) (60 min. TAT) 6. Prothrombin Time (PT) (60 min. TAT) 7. Fluid Cell Count (60 min. TAT) 8. Complete Urinalysis 9. D-dimer 10. Fluid pH CHEMISTRY 1. Arterial Blood Gases 2. Acetone 3. Ammonia 4. Amylase 5. Basic Metabolic Panel: Sodium, Potassium, Chloride, CO2, Creatinine, BUN, Glucose, and Calcium 6. Bilirubin (Total) 7. Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) 8. Calcium (Total and Ionized) 9. CPK (Total) (60 min. TAT for CPK total with MB fraction. CPKMB only run if CPK total > 113) UVM HEALTH NETWORK-CVPH 2 TEST MENU 10. Creatinine 11. CSF (Glucose and Protein) 12. Electrolytes: Sodium (Na), Potassium (K), Chloride (Cl), CO2 13. -

Effects of Hyperglycemia and Rapid Lowering of Plasma Glucose in Normal Rabbits

MILESTONES IN NEPHROLOGY J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1776–1788, 2000 Mark A. Knepper, Feature Editor Studies on Mechanisms of Cerebral Edema in Diabetic Comas EFFECTS OF HYPERGLYCEMIA AND RAPID LOWERING OF PLASMA GLUCOSE IN NORMAL RABBITS ALLEN I. ARIEFF AND CHARLES R. KLEEMAN WITH THE TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE OF ALICE KEUSHKERIAN AND HELEN BAGDOYAN From the Departments of Medicine, Wadsworth Veterans Administration Center and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, and the Cedars-Sinai Medical Research Institute, and University of California Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles, California 90048 with comments by ALLEN I. ARIEFF AND RICHARD STERNS Reprinted from J. Clin. Invest. 52:571–583, 1973 A BSTRACT To investigate the pathophysiology of cerebral edema occurring during treatment of diabetic coma, the effects of hyperglycemia and rapid lowering of plasma glucose were AUTHOR COMMENTARY evaluated in normal rabbits. During 2 h of hyperglycemia (plasma glucose = 61 mM), both brain (cerebral cortex) and Allen I. Arieff muscle initially lost about 10% of water content. After 4 h of hyperglycemia, skeletal muscle water content remained low University of California, but that of brain was normal. Brain osmolality (Osm) (343 San Francisco mosmol/kg H2O) was similar to that of cerebrospinal fluid Sausalito, California (CSF) (340 mosmol/kg), but increases in the concentration of Na+, K+, Cl–, glucose, sorbitol, lactate, urea, myoinositol, and amino acids accounted for only about half of this increase. n 1936, Dillon, Riggs, and Dyer described a syndrome The unidentified solute was designated “idiogenic osmoles”. Iwhereby individuals who were being treated for diabetic When plasma glucose was rapidly lowered to normal with coma and apparently recovering suddenly deteriorated, with insulin, there was gross brain edema, increases in brain content worsening of coma, respiratory insufficiency, hypotension, of water, Na+, K+, Cl– and idiogenic osmoles, and a signifi tachycardia, high fever, and death (1). -

Tests…But Maybe You Transports Don’T 2

11/12/15 Some things you should When lab tests are useful know about laboratory 1. Managing patients during critical care tests…But maybe you transports don’t 2. While transporting patient to medical facilities for evaluation of laboratory Steve Faynor, CCEMT-P abnormalities HCA Chippenham Medical Center Richmond Ambulance Authority Objectives 1. Review some basic laboratory tests. Treat the patient, not the 2. Appreciate how patterns of laboratory test results can offer insight into etiology. laboratory values. 3. Learn how laboratory test calculations can add additional clinical information. 4. Review some limitations of laboratory tests. ELECTROLYTES & A case of “bad labs” RENAL FUNCTION TESTS 1 11/12/15 Hypernatremia & Renal Failure Hypernatremia • 89 year old white female • Hyperaldosteronism • Coming from nursing home due to • Cushing’s disease or syndrome abnormal labs • Diabetes insipidus (deficiency of ADH) • Sodium 172 mmol/L • Dehydration • Potassium 4.2 mmol/L • Chloride 137 mmol/L • Carbon dioxide 21 mmol/L • What are some causes of hypernatremia? • BP 122/66, SBP 99 later • BUN 212 mg N/dL • HR 64/min • Creatinine 6.10 mg/dL • RR 21/min • What do these values indicate? • SpCO2 98% on 4 L oxygen per min • Does this change your therapy? • Tongue dry, skin turgor poor • What is the cause of the hypernatremia in this patient? Treatment? Acute Renal Failure Use of the BUN/creatinine ratio • Intrinsic renal disease • In intrinsic causes of acute renal failure, the – Acute tubular necrosis: ischemia, toxins BUN/creatinine ratio is typically 10-15. – Acute glomerulonephritis • In pre-renal causes of acute renal failure, – CKD with missed dialysis the BUN/creatinine ratio is typically >20. -

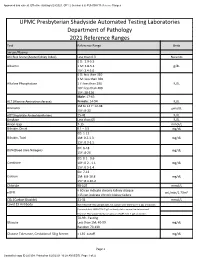

2021 Clinical Reference Ranges

Approved and current. Effective starting 6/23/2021. GP1 2 (version 6.6) PUH SHY Reference Ranges UPMC Presbyterian Shadyside Automated Testing Laboratories Department of Pathology 2021 Reference Ranges Test Reference Range Units Serum/Plasma AKI Risk Score (Acute Kidney Index) Less than 0.3 No units 0 D: 2.9-5.5 Albumin 1 M: 3.8-5.4 g/dL 15Y: 3.4-5.0 0 D: less than 310 1 M: less than 360 Alkaline Phosphatase 1 Y: less than 290 IU/L 10Y: less than 400 15Y: 38-126 Male: 17-63 ALT (Alanine Aminotransferase) Female: 14-54 IU/L 1M to 14 Y: 12-38 Ammonia µmol/L 15Y: 9-33 AST(Aspartate Aminotransferase) 15-41 IU/L Amylase Less than 65 IU/L Anion Gap 7-15 mmol/L Bilirubin, Direct 0.1 – 0.5 mg/dL 0D: 1-12 Bilirubin, Total 1M: 0.2-1.3 mg/dL 15Y: 0.3-1.5 0D: 6-18 BUN(Blood Urea Nitrogen) mg/dL 15Y: 8-26 0D: 0.1 - 0.6 Creatinine 10Y: 0.2 - 1.1 mg/dL 15Y: 0.5-1.4 0D: 7-12 Calcium 1M: 8.8-10.8 mg/dL 15Y: 8.4-10.2 Chloride 98-107 mmol/L < 60 can indicate chronic kidney disease eGFR mL/min/1.73m² <15 can indicate chronic kidney failure CO₂ (Carbon Dioxide) 21-31 mmol/L Covid 19 Antibody Non-Reactive-This sample does not contain anti-SARV-Co V -2 IgG antibodies Equivocal-Anti SARS-COV-2 IgG antibody status cannot be determined. -

Characteristics of Cerebrospinal Fluid in Tuberculous Meningitis Patients with Hydrocephalus Astrid Tamara Maajid Budiman,1 Nida Suraya,2 Ahmad Faried,3 Ida Parwati2

Original Article Characteristics of Cerebrospinal Fluid in Tuberculous Meningitis Patients with Hydrocephalus Astrid Tamara Maajid Budiman,1 Nida Suraya,2 Ahmad Faried,3 Ida Parwati2 1Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran 2Department of Clinical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran-Dr. Hasan Sadikin General Hospital, Bandung 3Department of Neurosurgery, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran-Dr. Hasan Sadikin General Hospital, Bandung Abstract Objective: meningitis (TBM) with hydrocephalus patients as diagnostic criteria of TBM. To describe cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) characteristics in tuberculous Methods: A cross-sectional using retrospective method was applied in this study by obtaining medical records of TBM with hydrocephalus patients that were treated at Department of Neurosurgery Dr. Hasan Sadikin General Hospital, Bandung from January 2014–September 2016. Results: Sixty one records were included in the study. Patient characteristics and differential count, protein, and glucose were recorded and descriptively such as age, gender, and CSF laboratory features such as color and clarity, cells 3 with analyzed.lymphocyte The predominance majority of CSF (median: macroscopic 76%). appearance Increased protein was seen from to benormal clear (88%) and colorless (88%). Median for CSF cell count was 25 cells/mm value range was seen in CSF (median: 50 mg/dL) while the mean for CSF glucose in this study remained in its normal value range (mean: 58.9±26.68 mg/dL)Conclusions: with lower CSF to blood glucose ratio (mean: 0.41±0.27). Received: November 2, 2017 Clear CSF with colorless appearance, lymphocyte pleocytosis, highNeurosurgery, protein level, Dr. Hasanand low Sadikin CSF glucose General as Hospital, well as blood Bandung. glucose ratio remain Revised: typical CSF characteristics of TBM patients found at the Department of Keywords: MayAccepted: 15, 2018 pISSN: 2302-1381; eISSN: 2338-4506; http://doi.org/10.15850/ijihs.v6n2.1129 IJIHS. -

Comparison of CSF Serum Albumin Index with CSF Glucose and CSF Proteins in Bacterial and Viral Meningitis

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Comparison of CSF Serum Albumin Index with CSF Glucose and CSF proteins in Bacterial and Viral Meningitis NAJAMUDDIN1, SYED RAZA JAFFAR2, FAWAD SANA3, ANWAR MAGSI4 ABSTRACT Background: Meningitis is one of the severe inflammation of covings of Brain and Spinal cord in developed countries with serious sequelale. With routine diagnostic procedures delay in diagnosis of meningitis may cause with grave result for the patients.To speed the diagnostic procedures a new diagnostic measure the cerebro spinal fluid serum albumin index has been introduced in detection of meningitis. Aim: To compare Cerebro Spinal Fluid Serum Albumin Index with CSF Glucose and CSF proteins in determination of bacterial and viral meningitis. Methods: A comparative cross section study was conducted in department of PNS Shifa Karachi from March 2014 to August 2015 on190 patients of 1-16 years of both sex with history of sign and symptoms of disease i.e., fever, headache, neck rigidity which were included in the study. Results: The summarized results of study showed the mean age as 13.875±1.414 years. Mean of CSF albumin in is .4299 g/l with SD 0.44353 while serum albumin in g/l mean is 38.03 and SD 4.488 and mean of CSF-serum albumin index is 11.7321. In student T test for CSF serum albumin index the mean of CSAI was 7.47±0.5. The sensitivity of the test is 91.09% and specificity is 96.4% while diagnostic accuracy is 94%. Conclusion: It is concluded that CSAI is a cost effective and efficient laboratory test for early diagnosis of bacterial and viral meningitis. -

Child Neurology: Differential Diagnosis of a Low CSF Glucose in Children and Young Adults Wilhelmina G

RESIDENT & FELLOW SECTION Child Neurology: Section Editor Differential diagnosis of a low CSF glucose Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, MS in children and young adults Wilhelmina G. Leen, MD ABSTRACT Cornelis J. de Wit, MD Analysis of CSF is daily routine in patients with acute neurologic disorders like CNS infections. Ron A. Wevers, PhD In those patients, the finding of a low CSF glucose may influence further diagnostic workup Baziel G. van Engelen, and therapeutic choices. The interpretation of a low CSF glucose in patients with a chronic neu- MD, PhD rologic disorder, however, is a less common practice. We present a practical overview on the dif- Erik-Jan Kamsteeg, PhD ferential diagnosis of a low CSF glucose and stress the importance of recognizing a low CSF Joerg Klepper, MD, PhD glucose as the diagnostic marker for GLUT1 deficiency syndrome, a treatable neurometabolic Marcel M. Verbeek, PhD* disorder. Neurology® 2013;81:e178–e181 Michèl A. Willemsen, MD, PhD* GLOSSARY GLUT1DS 5 GLUT1 deficiency syndrome. Correspondence to Analysis of CSF is routine in patients with acute neurologic disorders like CNS infections. Dr. Leen: [email protected] In those patients, the finding of a low CSF glucose (i.e., hypoglycorrhachia) can be deci- sive for further diagnostic and therapeutic management. In patients with a chronic neurologic disorder like intellectual disability or epilepsy, however, a low CSF glucose is easily over- looked, especially when other CSF parameters are normal.1 A low CSF glucose, though, is the diagnostic clue for GLUT1 deficiency syndrome (GLUT1DS), a treatable neurometabolic disorder.2 To develop a flow chart for the differential diagnosis of a low CSF glucose in neurologic disorders in children and young adults, we performed a literature search on Pubmed by using MeSH terms (CSF, glucose, CNS infections, CNS diseases) with subheadings (CSF, diagnosis), as well as free search terms such as GLUT1 deficiency syndrome, posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus, and ventri- culoperitoneal shunt.