Effects of Hyperglycemia and Rapid Lowering of Plasma Glucose in Normal Rabbits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS) Erica Kretchman DO October 19 2018 Speaker for Valeritas, Medtronic, Astrazenica, Boehringer Ingelheim

Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS) Erica Kretchman DO October 19 2018 Speaker for Valeritas, Medtronic, AstraZenica, Boehringer Ingelheim. These do not influence this presentation Objective • Review and understand diagnosis of Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS) and differentiating from Diabetic Ketoacidosis • Treatment of HHS • Complications of HHS Question 1 • Which of the following is NOT a typical finding in HHS? 1. Blood PH <7.30 2. Dehydration 3. Mental Status Changes 4. Osmotic diuresis Question 2 • Hypertonic fluids, such as 3% saline, are the first line of treatment to correct dehydration in HHS 1. True 2. False Question 3 • Which of the following statements is INCORRECT about Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State? 1. HHS occurs mainly in type 2 diabetics. 2. This condition presents without ketones in the urine. 3. Metabolic alkalosis presents in severe HHS. 4. Intravenous Regular insulin is used to treat hyperglycemia. Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS) • HHS and DKA are of two of the most serious complications form Diabetes • Hospital admissions for HHS are lower than the rate for DKA and accounts for less than 1 percent of all primary diabetic admissions • Mortality rate for patients with HHS is between 10 and 20 percent, which is approximately 10 times higher than that for DKA • Declined between 1980 and 2009 • Typically from precipitating illness - rare from HHS itself PRECIPITATING FACTORS • The most common events are infection (often pneumonia or urinary tract infection) and discontinuation of or inadequate insulin -

Effect on Ca++. the Clinical Significance of This Observation Re- Suggest That Physiologic Jaundice Results from a Markedly In- Quires Further Evaluation

ABSTRACTS 413 effect on Ca++. The clinical significance of this observation re- suggest that physiologic jaundice results from a markedly in- quires further evaluation. creased load of bilirubin presented to the liver either from increased bilirubin synthesis or enhanced intestinal reabsorb- Controlled clinical trial of phenobarbital (PB) and light for tion and marked limitation in the capacity to conjugate. management of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia in a predomi- Studies performed at 4 hours of age in a monky born 2 weeks nant Negro population. O. S. VALDES, H. M. MAURER, C. N. post-maturely revealed that hepatic transport and conjugation SHUMWAY, D. DRAPER, and A. HOSSAINI. Med. Coll. of Virginia, of bilirubin was fully mature, indicating that maturation of Richmond, Va. (Intr. by W. E. Laupus). each of these functions may occur in utero. Low birth weight infants, less than 24 hrs of age, were randomly assigned to receive either oral PB, 5 mg/kg/day for 5 A controlled study of intravenous fibrin hydrolysate supple- days, blue light (200-300 footcandles) continuously for 4 days, a ment in prematures <1.3 kg. M. HEATHER BRYAN, PATRICK combination of PB and light, or no treatment. 90% or more of WEI, RICHARD HAMILTON, SANFORD H. JACKSON, INGEBORC C. the infants in each group were Negroes. Infants with a positive RADDE, GRAHAM W. CHANCE, and PAUL R. SWYER. Univ. of Coomb's test were excluded. Toronto and The Research Inst., The Hosp. for Sick Children, Toronto, Ont. Canada. We have compared the effect of early supplemental intra- Total serum bilirubin concentration, mg% (mean ± S.E.) venous 3.5% fibrin hydrolysate plus 10% dextrose to 10% No. -

Cerebrospinal Fluid in Critical Illness

Cerebrospinal Fluid in Critical Illness B. VENKATESH, P. SCOTT, M. ZIEGENFUSS Intensive Care Facility, Division of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, Royal Brisbane Hospital, Brisbane, QUEENSLAND ABSTRACT Objective: To detail the physiology, pathophysiology and recent advances in diagnostic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in critical illness, and briefly review the pharmacokinetics and pharmaco- dynamics of drugs in the CSF when administered by the intravenous and intrathecal route. Data Sources: A review of articles published in peer reviewed journals from 1966 to 1999 and identified through a MEDLINE search on the cerebrospinal fluid. Summary of review: The examination of the CSF has become an integral part of the assessment of the critically ill neurological or neurosurgical patient. Its greatest value lies in the evaluation of meningitis. Recent publications describe the availability of new laboratory tests on the CSF in addition to the conventional cell count, protein sugar and microbiology studies. Whilst these additional tests have improved our understanding of the pathophysiology of the critically ill neurological/neurosurgical patient, they have a limited role in providing diagnostic or prognostic information. The literature pertaining to the use of these tests is reviewed together with a description of the alterations in CSF in critical illness. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs in the CSF, when administered by the intravenous and the intrathecal route, are also reviewed. Conclusions: The diagnostic utility of CSF investigation in critical illness is currently limited to the diagnosis of an infectious process. Studies that have demonstrated some usefulness of CSF analysis in predicting outcome in critical illness have not been able to show their superiority to conventional clinical examination. -

CSF Xanthochromia

CSF Xanthochromia Pseudonyms – CSF bilirubin For investigation of suspected subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) in CT negative patients Xanthochromia is the yellow discoloration indicating the presence of bilirubin in CSF which appears as oxyhaemoglobin released from the breakdown of red blood cells following haemorrhage into the CSF is converted in vivo into bilirubin in a time‐dependent manner. A subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is a spontaneous arterial bleeding into the subarachnoid space, usually from a cerebral aneurysm, and characterised by a severe sudden‐onset headache. The majority of positive cases are detected by computed tomography (CT) scanning but for those CT‐ negative patients presenting with a history suggestive of SAH the measurement of xanthochromia in CSF is advocated to detect those patients who actually have sustained a SAH and require treatment and to eliminate the possibility of SAH in the remainder without the need of confirmatory angiography. The CSF is collected by means of lumbar puncture (LP). For full interpretation of the result other CSF and blood tests must be collected at the same time – CSF protein and glucose; plasma glucose; and serum protein and bilirubin. General information CSF Xanthochromia sample collection kits are provided in the ACU (ORC) and AMU (Trafford) and also available from the Specimen Receptions at the laboratories at both sites. Concurrent samples should be requested for CSF protein and glucose, plasma glucose and serum LFTS (for protein and bilirubin) using the sample containers supplied. Collection container: CSF xanthochromia: White topped Universal container (In addition the following samples should be collected:‐ CSF glucose & protein: 1.2 mL fluoride‐EDTA glucose (Sarstedt yellow top) Serum protein & bilirubin: 4.9 mL SST (Sarstedt brown top) Plasma glucose: 2.7 mL fluoride‐EDTA glucose (Sarstedt yellow top) Type and volume of sample: 1 mL CSF requested, minimum 400 µL required for analysis Specimen transport/special precautions: A CSF Xanthochromia sample collection kit should be used. -

Severe Hyponatremia with Hypouricemia in a Patient with Medullary Hemorrhage: a Case Report

SUTIRTHA CHAKRABORTY, TAPAS K BANERJEE SEVERE HYPONATREMIA WITH HYPOURICEMIA IN A PATIENT WITH MEDULLARY HEMORRHAGE: A CASE REPORT The Journal of the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine SEVERE HYPONATREMIA WITH HYPOURICEMIA IN A PATIENT WITH MEDULLARY HEMORRHAGE: A CASE REPORT Sutirtha Chakraborty1, Tapas K Banerjee2 1Consultant & Chief, Dept. of Biochemistry, Peerless Hospital & B K Roy Research Centre, Kolkata 700094, India 2Sr. Consultant & Head, Dept. of Neurology, National Neurosciences Centre, Peerless Hospital, Kolkata,India Corresponding Author: Dr Sutirtha Chakraborty, MD Consultant & Chief, Dept. of Biochemistry Peerless Hospital & B K Roy Research Centre, Kolkata 700094 , India e‐mail: [email protected] Mobile +91 9874787638 ABSTRACT Hyponatremia is the commonest electrolyte abnormality in hospitalized patients and occurs due to various causes. Here we present a case of SIADH who was diagnosed using commonly available biochemical tests. This case report also discusses the interaction of the laboratory physician with the treating clinician and the approach needed to arrive at a correct diagnosis. It highlights the importance of serum uric acid and fractional excretion of urinary uric acid in the diagnosis of SIADH. It also discusses the approach needed to distinguish SIADH from Cerebral Salt wasting syndrome, where the presenting feature is also hyponatremia. KEY WORDS Hyponatremia, SIADH, Uric Acid. CASE REPORT A 68 year old gentleman was admitted to the Dept. of Neurology with a history of sudden onset uneasiness followed by slurring of speech and giddiness. Examination by the Consultant Neurologist showed that he was conscious and obeying commands with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 14/15.Power was grade 4/5 in all four limbs and DTRs preserved. -

Diagnostic Accuracy of Calculated Serum Osmolarity to Predict Dehydration in Older People: Adding Value to Pathology Laboratory Reports

Open Access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008846 on 21 October 2015. Downloaded from Diagnostic accuracy of calculated serum osmolarity to predict dehydration in older people: adding value to pathology laboratory reports Lee Hooper,1 Asmaa Abdelhamid,1 Adam Ali,1 Diane K Bunn,1 Amy Jennings,1 W Garry John,2 Susan Kerry,2 Gregor Lindner,3 Carmen A Pfortmueller,4 Fredrik Sjöstrand,5 Neil P Walsh,6 Susan J Fairweather-Tait,1 John F Potter,1,2 Paul R Hunter,1,2 Lee Shepstone1 To cite: Hooper L, ABSTRACT et al Strengths and limitations of this study Abdelhamid A, Ali A, . Objectives: To assess which osmolarity equation best Diagnostic accuracy of predicts directly measured serum/plasma osmolality ▪ – calculated serum osmolarity Dehydration has become a generic term we and whether its use could add value to routine blood to predict dehydration in have clearly described dehydration type (water- older people: adding value to test results through screening for dehydration in older loss dehydration) and used serum osmolality, pathology laboratory reports. people. the correct reference standard. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008846. Design: Diagnostic accuracy study. ▪ Assessment of equations in five different groups doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015- Participants: Older people (≥65 years) in 5 cohorts: of older people including healthy free-living older 008846 Dietary Strategies for Healthy Ageing in Europe people, frailer people living in residential care, (NU-AGE, living in the community), Dehydration and older people visiting emergency care or ▸ Prepublication history and Recognition In our Elders (DRIE, living in residential staying in hospital, living in several European additional material is care), Fortes (admitted to acute medical care), countries, and including men and women, available. -

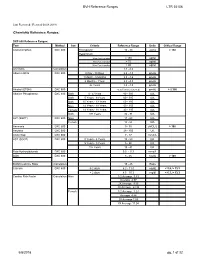

BVH Reference Ranges LTR 35106 Chemistry Reference Ranges

BVH Reference Ranges LTR 35106 Last Reviewed: (Revised 05.08.2018) Chemistry Reference Ranges: DXC 600 Reference Ranges: Test Method Sex Criteria Reference Range Units Critical Range Acetaminophen DXC 600 Therapeutic 10 - 30 ug/mL > 150 Hepatotoxic 4 hrs Post Ingestion > 150 ug/ml 8 hrs Post Ingestion > 75 ug/ml 12 hrs Post Ingestion > 40 ug/ml A/G Ratio Calculation 1.1 - 2.2 Albumin BCG DXC 600 0 Day - 30 Days 2.6 - 4.3 gm/dL 1 Month - 5 Months 2.8 - 4.6 gm/dL 6 Months - 1Year 2.8 - 4.8 gm/dL 2+ Years 3.2 - 4.9 gm/dL Alcohol (ETOH) DXC 600 <0.005 (none detected) gm/dL > 0.300 Alkaline Phosphatase DXC 600 Both 0 - 4 Years 80 - 350 IU/L Both 5 Years - 9 Years 60 - 385 IU/L Both 10 Years - 13 Years 60 - 485 IU/L Male 14 Years - 18 Years 50 - 350 IU/L Female 14 Years - 18 Years 40 - 195 IU/L Both 19+ Years 32 - 91 IU/L ALT (SGPT) DXC 600 Male 17 - 63 IU/L Female 14 - 54 IU/L Ammonia DXC 600 9 - 35 uMOL/L > 100 Amylase DXC 600 28 - 100 U/L Anion Gap DXC 600 7 - 17 mmol/L AST (SGOT) DXC 600 0 Years - 4 Years 10 - 60 IU/L 5 Years - 9 Years 5 - 50 IU/L 10+ Years 15 - 41 IU/L Beta Hydroxybutyrate DXC 600 0.0 - 0.3 mmol/L BUN DXC 600 8 - 26 mg/dL > 100 BUN/Creatinine Ratio Calculation 15 - 25 Ratio Calcium DXC 600 0-2 days 6.2 - 11.0 mg/dL < 5.8, > 13.3 > 2 days 8.5 - 10.3 mg/dl < 6.3, > 13.3 Cardiac Risk Factor Calculation Male 1/2 Average 3.43 Average 4.97 2X Average 9.55 3X Average 23.99 Female 1/2 Average 3.27 Average 4.44 2X Average 7.05 3X Average 11.04 5/8/2018 pg. -

Using Osmolality to Diagnose and Treat Hyponatremia in Covid-19 Patients

SCIENTIFIC RESOURCE USING OSMOLALITY TO DIAGNOSE AND TREAT HYPONATREMIA IN COVID-19 PATIENTS ARTICLE SUMMARY Recent publications have shown that COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019), an infectious disease caused by a novel coronavirus known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), is associated with electrolyte disorders including hyponatremia.1,2,3 Early diagnosis and etiologic determination are critical in any hyponatremic patient to ensure proper treatment and to avoid potential harm to the patient.4,5 Osmolality testing is quick, inexpensive and effective to help with early detection and diagnosis of hyponatremia.6 Osmolality testing can help ensure that appropriate treatment strategies are implemented early for hyponatremic patients which may be even more significant in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.5,7,8 As clinicians and researchers continue to expand their understanding of COVID-19, additional laboratory testing is important to consider to help better understand and diagnose a COVID-19 patient’s underlying conditions. OSMOLALITY TESTING CAN HELP WITH EARLY DIAGNOSIS AND ETIOLOGICAL DETERMINATION OF HYPONATREMIA, WHICH IS CRITICAL FOR THIS PATIENT POPULATION As association between COVID-19 of hyponatremia. The use of urine and respiratory failure. and hyponatremia has been shown in osmolality to establish a correct Understanding the the literature.1,2,3 Hyponatremia is an underlying diagnosis of hyponatremia is underlying causes electrolyte disorder that occurs when critical to avoid inappropriate treatment -

Routine Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis

CHAPTER4 Routine cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis a b a ) F. Deisenhammer, A. Bartos, R. Egg, Albumin CSF/serum ratio (Qalb should be pre- N. E. Gilhus,c G. Giovannoni,d S. Rauer,e ferred to total protein measurement and normal F. Sellebjergf upper limits should be related to patients’ age. Elevated Qalb is a non-specific finding but occurs mainly in bacterial, cryptococcal, and tubercu- Background A great variety of neurological diseases lous meningitis, leptomingeal metastases as well require investigation of the cerebrospinal fluid as acute and chronic demyelinating polyneu- (CSF) to prove the diagnosis or to rule out relevant ropathies. differential diagnoses. Pathological decrease of the CSF/serum glu- cose ratio or an increase in lactate concentration Objectives To evaluate the theoretical background indicates bacterial or fungal meningitis or lep- and provide guidelines for clinical use in rou- tomeningeal metastases. tine CSF analysis including total protein, albumin, Intrathecal immunoglobulin G synthesis is best immunoglobulins, glucose, lactate, cell count, demonstrated by isoelectric focusing followed by cytological staining, and investigation of infec- specific staining. tious CSF. Cellular morphology (cytological staining) should be evaluated whenever pleocytosis is found or Methods Systematic Medline search for the above leptomeningeal metastases or pathological bleed- mentioned variables. Review of appropriate publi- ing is suspected. Computed tomography-negative cations by one or more of the task force members. intrathecal bleeding should be investigated by Grading of evidence and recommendations was bilirubin detection. based on consensus by all task force members. Introduction CSF should be analysed immediately after collec- tion. If storage is needed 12 ml of CSF should The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a dynamic, be partitioned into three to four sterile tubes. -

D40. Cerebrospinal Fluid.Pdf

CEREBROSPINAL FLUID D40 (1) Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Last updated: June 3, 2019 PHYSIOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................ 1 CSF PRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 CSF REABSORPTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 PARAMETERS ........................................................................................................................................... 2 NORMAL ................................................................................................................................................ 2 OPENING PRESSURE ................................................................................................................................ 3 COLOR ................................................................................................................................................... 3 BLOODY CSF ......................................................................................................................................... 3 VISCOSITY & TURBIDITY ....................................................................................................................... 4 CELLS ................................................................................................................................................... -

2017 LAB GUIDE TEST MENU March 2017Edition

2017 LAB GUIDE TEST MENU March 2017Edition Replaces: Sept 2015 Edition STAT TESTING MENU (2 Pages) 30 Minute In-Lab Turnaround Time (TAT) Unless Further Noted Below (In-Lab Time) MICROBIOLOGY 1. Spinal Fluid Culture set up and Gram Stain of sediment, India Ink prep 2. Gram Stain, other sites 3. Planting of cultures 4. Wet prep 5. Rapid Strep A Antigen Test (15 min. TAT) 6. Rapid Influenza A & B Antigen test 7. Rapid RSV Antigen test 8. Malaria Prep (60 min. TAT), Evening and Night shifts will only report “Parasites present or absent” 9. Screen, Gastric Urease, for Helicobacter Pylori (60 min. TAT) 10. Clostridium difficile DNA amplification (60 min. TAT) BLOOD BANK 1. Compatibility testing (leuko-reduced packed cells) 2. Type and Screen (60 min. TAT) 3. Cord Blood (2 hours) HEMATOLOGY 1. Complete Blood Count (CBC) SEE NOTE #1 2. Fibrinogen 3. Hemogram (ABC) 4. Monospot Test 5. Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT) (60 min. TAT) 6. Prothrombin Time (PT) (60 min. TAT) 7. Fluid Cell Count (60 min. TAT) 8. Complete Urinalysis 9. D-dimer 10. Fluid pH CHEMISTRY 1. Arterial Blood Gases 2. Acetone 3. Ammonia 4. Amylase 5. Basic Metabolic Panel: Sodium, Potassium, Chloride, CO2, Creatinine, BUN, Glucose, and Calcium 6. Bilirubin (Total) 7. Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) 8. Calcium (Total and Ionized) 9. CPK (Total) (60 min. TAT for CPK total with MB fraction. CPKMB only run if CPK total > 113) UVM HEALTH NETWORK-CVPH 2 TEST MENU 10. Creatinine 11. CSF (Glucose and Protein) 12. Electrolytes: Sodium (Na), Potassium (K), Chloride (Cl), CO2 13. -

Water Deprivation Test and Desmopressin Test in Adults

BLOOD SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF CLINICAL BIOCHEMISTRY Title of Document: Water Deprivation Test in Adults Q Pulse Reference No: BS/CB/DCB/EN/16 Version NO: 5 Authoriser: Sadie Redding Page 1 of 4 WATER DEPRIVATION TEST Introduction Diabetes insipidus (DI) involves deficient production or lack of effective action of antidiuretic hormone (ADH or arginine vasopressin). ADH stimulates the kidney to conserve fluid. Deficient production of ADH or lack of effective action of ADH causes a high urine output, thirst, dehydration, and low blood pressure in advanced cases. Disease of the hypothalamus/pituitary gland leading to a deficiency in ADH production is called cranial or central DI. Disease of the kidney leading to lack of response of the kidney to fluid conserving action of ADH is called nephrogenic DI. The principle of the water deprivation test is to assess the ability of the patient to concentrate urine when fluids are withheld. Water deprivation should normally cause increased secretion of ADH, resulting in the production of small volumes of concentrated urine. Initial tests Polyuria should be confirmed by 24hour urine volume. Rule out diabetes, UTI, hypercalcaemia, hypokalaemia, renal failure and thyrotoxicosis. Morning urine osmolality >600mOsm/kg rules out DI and therefore a water deprivation test is not necessary. Preparation Please contact the Duty Biochemist at least 24 hours before the test (ext.48437) Normal dinner and fluids are allowed the night before the test. No alcohol or caffeine. 7am light breakfast but NO fluids, tea, coffee or smoking. Supervision is required throughout to assess compliance and safety. Contraindications Hypovolaemia or hypernatraemia Procedure Print out a worksheet and record results in the table (appendix 1).