Cerebrospinal Fluid in Critical Illness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatially Heterogeneous Choroid Plexus Transcriptomes Encode Positional Identity and Contribute to Regional CSF Production

The Journal of Neuroscience, March 25, 2015 • 35(12):4903–4916 • 4903 Development/Plasticity/Repair Spatially Heterogeneous Choroid Plexus Transcriptomes Encode Positional Identity and Contribute to Regional CSF Production Melody P. Lun,1,3 XMatthew B. Johnson,2 Kevin G. Broadbelt,1 Momoko Watanabe,4 Young-jin Kang,4 Kevin F. Chau,1 Mark W. Springel,1 Alexandra Malesz,1 Andre´ M.M. Sousa,5 XMihovil Pletikos,5 XTais Adelita,1,6 Monica L. Calicchio,1 Yong Zhang,7 Michael J. Holtzman,7 Hart G.W. Lidov,1 XNenad Sestan,5 Hanno Steen,1 XEdwin S. Monuki,4 and Maria K. Lehtinen1 1Department of Pathology, and 2Division of Genetics, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, 3Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 02118, 4Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of California Irvine School of Medicine, Irvine, California 92697, 5Department of Neurobiology and Kavli Institute for Neuroscience, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut 06510, 6Department of Biochemistry, Federal University of Sa˜o Paulo, Sa˜o Paulo 04039, Brazil, and 7Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Washington University, St Louis, Missouri 63110 A sheet of choroid plexus epithelial cells extends into each cerebral ventricle and secretes signaling factors into the CSF. To evaluate whether differences in the CSF proteome across ventricles arise, in part, from regional differences in choroid plexus gene expression, we defined the transcriptome of lateral ventricle (telencephalic) versus fourth ventricle (hindbrain) choroid plexus. We find that positional identitiesofmouse,macaque,andhumanchoroidplexiderivefromgeneexpressiondomainsthatparalleltheiraxialtissuesoforigin.We thenshowthatmolecularheterogeneitybetweentelencephalicandhindbrainchoroidplexicontributestoregion-specific,age-dependent protein secretion in vitro. -

Human Cerebrospinal Fluid Induces Neuronal Excitability Changes in Resected Human Neocortical and Hippocampal Brain Slices

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/730036; this version posted August 8, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. Human cerebrospinal fluid induces neuronal excitability changes in resected human neocortical and hippocampal brain slices Jenny Wickham*†1, Andrea Corna†1,2,3, Niklas Schwarz4, Betül Uysal 2,4, Nikolas Layer4, Thomas V. Wuttke4,5, Henner Koch4, Günther Zeck1 1 Neurophysics, Natural and Medical Science Institute (NMI) at the University of Tübingen, Reutlingen, Germany 2 Graduate Training Centre of Neuroscience/International Max Planck Research School, Tübingen, Germany. 3 Institute for Ophthalmic Research, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany 4 Department of Neurology and Epileptology, Hertie-Institute for Clinical Brain Research, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany 5 Department of Neurosurgery, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany * Communicating author: Jenny Wickham ([email protected]) and Günther Zeck ([email protected]) † shared first author, Shared last author Acknowledgments: This work was supported by the German Ministry of Science and Education (BMBF, FKZ 031L0059A) and by the German Research Foundation (KO-4877/2-1 and KO 4877/3- 1) Author contribution: JW and AC performed micro-electrode array recordings, NS, BU, NL, TW, HK and JW did tissue preparation and culturing, JW, AC, GZ did data analysis and writing. Proof reading and study design: all. Conflict of interest: None Keywords: Human tissue, human cerebrospinal fluid, Microelectrode array, CMOS-MEA, hippocampus, cortex, tissue slice 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/730036; this version posted August 8, 2019. -

The Diagnosis of Subarachnoid Haemorrhage

Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1990;53:365-372 365 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.53.5.365 on 1 May 1990. Downloaded from OCCASIONAL REVIEW The diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage M Vermeulen, J van Gijn Lumbar puncture (LP) has for a long time been of 55 patients with SAH who had LP, before the mainstay of diagnosis in patients who CT scanning and within 12 hours of the bleed. presented with symptoms or signs of subarach- Intracranial haematomas with brain shift was noid haemorrhage (SAH). At present, com- proven by operation or subsequent CT scan- puted tomography (CT) has replaced LP for ning in six of the seven patients, and it was this indication. In this review we shall outline suspected in the remaining patient who stop- the reasons for this change in diagnostic ped breathing at the end of the procedure.5 approach. In the first place, there are draw- Rebleeding may have occurred in some ofthese backs in starting with an LP. One of these is patients. that patients with SAH may harbour an We therefore agree with Hillman that it is intracerebral haematoma, even if they are fully advisable to perform a CT scan first in all conscious, and that withdrawal of cerebro- patients who present within 72 hours of a spinal fluid (CSF) may occasionally precipitate suspected SAH, even if this requires referral to brain shift and herniation. Another disadvan- another centre.4 tage of LP is the difficulty in distinguishing It could be argued that by first performing between a traumatic tap and true subarachnoid CT the diagnosis may be delayed and that this haemorrhage. -

Introduction Neuroimaging of the Brain

Introduction Neuroimaging of the Brain John J. McCormick MD Normal appearance depends on age Trauma • One million ER visits/yr • 80,000/yr develop long term disability • 50,000/yr die • 46% from transportation; 26% falls; 17% assaults. Other causes, such as sports injuries, account for rest. • 2/3 < 30yrs old • Men 2X as likely to be injured • Cost of TBI is $48.3 billion annually • A patient in mid-twenties with severe head injury is estimated to have a lifetime cost of 4 million dollars including lost work hours, medical and daily care Skull Fracture • Linear or depressed • Skull base, middle meningeal artery • Differentiate from suture and venous channels Sutures Traumatic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Acute Subdural Hemorrhage Subacute Subdural Hematoma Chronic Subdural Hemorrhage Epidural Hematoma Diffuse Axonal Injury Coup-Contracoup Intraventricular Hemorrhage Stroke National Stroke Ass’n Stats • Third leading cause of death in US • Someone suffers stroke every 53 seconds and every 3.3 minutes someone dies of a stroke • 28% of those who suffer from stroke are under 65 • 15-30% are permanently disabled and require institutional care • Estimated direct and indirect annual cost of stroke un US is 43.4 billion dollars Stroke Subtypes • Two major types: hemorrhagic and ischemic • Hemmorrhagic strokes caused by blood vessel rupture and account for 16% of strokes • Ischemic strokes include thrombotic, embolic, lacunar and hypoperfusion infarctions Intracebral Hemorrhage • Most common cause: hypertensive hemorrhage • Other causes: AVM, coagulopathy, -

Successful Management of Nosocomial Ventriculitis and Meningitis Caused by Extensively Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii in Austria

CASE REPORT Successful management of nosocomial ventriculitis and meningitis caused by extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Austria M Hoenigl MD1,2*, M Drescher1*, G Feierl MD3, T Valentin MD1, G Zarfel PhD3, K Seeber MSc1, R Krause MD1, AJ Grisold MD3 M Hoenigl, M Drescher, G Feierl, et al. Successful management La prise en charge réussie d’une ventriculite et of nosocomial ventriculitis and meningitis caused by extensively d’une méningite d’origine nosocomiale causées par drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Austria. Can J Infect un Acinetobacter baumannii d’une extrême Dis Med Microbiol 2013;24(3):e88-e90. résistance aux médicaments en Autriche Nosocomial infections caused by the Gram-negative coccobacillus Les infections d’origine nosocomiale causées par le coccobacille Acinetobacter baumannii have substantially increased over recent years. Acinetobacter baumannii Gram négatif ont considérablement augmenté Because Acinetobacter is a genus with a tendency to quickly develop ces dernières années. Puisque l’Acinetobacter est un genre qui a ten- resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents, therapy is often compli- dance à devenir rapidement résistant à de multiples agents antimicro- cated, requiring the return to previously used drugs. The authors report biens, le traitement est souvent compliqué et exige de revenir à des a case of meningitis due to extensively drug-resistant A baumannii in an médicaments déjà utilisés. Les auteurs signalent un cas de méningite Austrian patient who had undergone neurosurgery in northern Italy. attribuable à un A baumannii d’une extrême résistance aux médica- The case illustrates the limits of therapeutic options in central nervous ments chez un patient autrichien qui a subi une neurochirurgie dans le system infections caused by extensively drug-resistant pathogens. -

CSF Xanthochromia

CSF Xanthochromia Pseudonyms – CSF bilirubin For investigation of suspected subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) in CT negative patients Xanthochromia is the yellow discoloration indicating the presence of bilirubin in CSF which appears as oxyhaemoglobin released from the breakdown of red blood cells following haemorrhage into the CSF is converted in vivo into bilirubin in a time‐dependent manner. A subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is a spontaneous arterial bleeding into the subarachnoid space, usually from a cerebral aneurysm, and characterised by a severe sudden‐onset headache. The majority of positive cases are detected by computed tomography (CT) scanning but for those CT‐ negative patients presenting with a history suggestive of SAH the measurement of xanthochromia in CSF is advocated to detect those patients who actually have sustained a SAH and require treatment and to eliminate the possibility of SAH in the remainder without the need of confirmatory angiography. The CSF is collected by means of lumbar puncture (LP). For full interpretation of the result other CSF and blood tests must be collected at the same time – CSF protein and glucose; plasma glucose; and serum protein and bilirubin. General information CSF Xanthochromia sample collection kits are provided in the ACU (ORC) and AMU (Trafford) and also available from the Specimen Receptions at the laboratories at both sites. Concurrent samples should be requested for CSF protein and glucose, plasma glucose and serum LFTS (for protein and bilirubin) using the sample containers supplied. Collection container: CSF xanthochromia: White topped Universal container (In addition the following samples should be collected:‐ CSF glucose & protein: 1.2 mL fluoride‐EDTA glucose (Sarstedt yellow top) Serum protein & bilirubin: 4.9 mL SST (Sarstedt brown top) Plasma glucose: 2.7 mL fluoride‐EDTA glucose (Sarstedt yellow top) Type and volume of sample: 1 mL CSF requested, minimum 400 µL required for analysis Specimen transport/special precautions: A CSF Xanthochromia sample collection kit should be used. -

Thunderclap Headache and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Thunderclap Headache and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage W David Freeman, MD No conflicts of interest or disclosures Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Neurocrit Care. 2017 Sep;27(Suppl 1):116- 123. doi: 10.1007/s12028-017-0458-8. Objectives •Recognize the symptoms (thunderclap headache) and Subarachnoid signs of SAH Hemorrhage •Initiate workup for suspected SAH •Initial management of SAH patient Case • 39 year old woman presents with severe headache, uncertain time of onset, associated with nausea • PMH: long history of migraine headaches • Meds: • Reports taking ibuprofen prior to ED, with moderate improvement of headache • Taking warfarin for a pelvic DVT - year prior during pregnancy • Exam: sleepy, yet follows commands, left eye droop and dilated pupil, moving all extremities • BP 160/95 mmHg, RR 24/min, HR 98/min • Breathing shallow and rapid, airway protection uncertain Initial Checklist in Emergency Dept. ☐ Brain Imaging ☐ Labs: PT/PTT, CBC, electrolytes, BUN, Cr, troponin, toxicology screen ☐ 12 lead ECG ☐ Blood pressure goal established ☐ Consult neurosurgery ☐ Address hydrocephalus SAH Algorithm Neurocrit Care. 2017 Sep;27(Suppl 1):116- 123. doi: 10.1007/s12028-017-0458-8. SAH Symptoms and Signs CLASSIC NOT-SO-CLASSIC Abrupt onset of severe headache (HA), HA is not reported as abrupt (patient may i.e. thunderclap not remember event well) “Worst or first” headache of one’s life HA responds well to non-narcotic that is instantaneously maximal at onset analgesics (“thunderclap” after lightening strike) May have nausea, vomiting and neck pain HA -

Of CMV Ventriculitis CMV Ventriculoencephalitis Is Characterized by Sub- Acute Delirium, Cranial Neuropathies, and Nystagmus

Alzhemier’s disease in women: randomized, double-blind, 23. Crystal H, Dickson D, Fuld P, et al. Clinico-pathologic studies placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 2000;54:295–301. in dementia-nondemented subjects with pathologically con- 22. Mulnard RA, Cotman CW, Kawas C, et al. Estrogen replace- firmed Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1988;38:1682–1687. ment therapy for treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s 24. Price JL, Morris JC. Tangles and plaques in nondemented disease: a randomized control trial. Alzheimer’s Disease aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 1999; Coopertive Study. JAMA 2000;283:1007–1015. 45:358–368. NeuroImages Figure. (A) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MRI sequence demonstrates prominent abnormal signal outlining the ventricles. (B) Cytomegalovirus (CMV)-infected macrophages in a patient with CMV ventriculoencephalitis. “Owl’s eyes” of CMV ventriculitis CMV ventriculoencephalitis is characterized by sub- acute delirium, cranial neuropathies, and nystagmus. The Devon I. Rubin, MD, Rochester, MN pathologic hallmark is the cytomegalic cell, a macrophage A 35-year-old HIV-positive man with a history of cyto- containing intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions of megalovirus (CMV) retinitis presented with fever, diplopia, cytomegalic virus particles, resembling and referred to as and progressive obtundation over 1 week. Neurologic ex- “owl’s eyes” (figure, B). MRI findings in CMV ventriculoen- amination revealed a fluctuating level of alertness, bilat- cephalitis include diffuse cerebral atrophy, progressive eral gaze-evoked horizontal nystagmus, a left facial palsy, ventriculomegaly, and a variable degree of periventricular and diffuse areflexia. MRI demonstrated generalized atro- or subependymal contrast enhancement.1 Newer imaging phy and ventriculomegaly with increased signal in the left sequences, such as FLAIR, may be more sensitive in de- caudate head on T1-weighted, gadolinium-enhanced im- tecting ventricular abnormalities. -

Hypothesis on the Pathophysiology of Syringomyelia Based on Simulation of Cerebrospinal Fluid Dynamics H S Chang, H Nakagawa

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.74.3.344 on 1 March 2003. Downloaded from 344 PAPER Hypothesis on the pathophysiology of syringomyelia based on simulation of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics H S Chang, H Nakagawa ............................................................................................................................. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:344–347 See end of article for authors’ affiliations ....................... Objectives: Despite many hypotheses, the pathophysiology of syringomyelia is still not well Correspondence to: understood. In this report, the authors propose a hypothesis based on analysis of cerebrospinal fluid Dr H S Chang, Department of Neurological Surgery, dynamics in the spine. Aichi Medical University, Methods: An electric circuit model of the CSF dynamics of the spine was constructed based on a tech- 21 Yazako-Karimata, nique of computational fluid mechanics. With this model, the authors calculated how a pulsatile CSF Nagakute-cho, Aichi-gun, wave coming from the cranial side is propagated along the spinal cord. Aichi 480–1195, Japan; Results: Reducing the temporary fluid storage capacity of the cisterna magna dramatically increased [email protected] the pressure wave propagated along the central canal. The peak of this pressure wave resided in the Received 14 June 2002 mid-portion of the spinal cord. In final revised form Conclusions: The following hypotheses are proposed. The cisterna magna functions as a shock 11 November 2002 Accepted absorber against the pulsatile CSF waves coming from the cranial side. The loss of shock absorbing 21 November 2002 capacity of the cisterna magna and subsequent increase of central canal wall pressure leads to syrinx ....................... formation in patients with Chiari I malformation. -

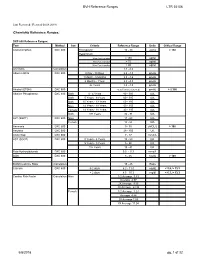

BVH Reference Ranges LTR 35106 Chemistry Reference Ranges

BVH Reference Ranges LTR 35106 Last Reviewed: (Revised 05.08.2018) Chemistry Reference Ranges: DXC 600 Reference Ranges: Test Method Sex Criteria Reference Range Units Critical Range Acetaminophen DXC 600 Therapeutic 10 - 30 ug/mL > 150 Hepatotoxic 4 hrs Post Ingestion > 150 ug/ml 8 hrs Post Ingestion > 75 ug/ml 12 hrs Post Ingestion > 40 ug/ml A/G Ratio Calculation 1.1 - 2.2 Albumin BCG DXC 600 0 Day - 30 Days 2.6 - 4.3 gm/dL 1 Month - 5 Months 2.8 - 4.6 gm/dL 6 Months - 1Year 2.8 - 4.8 gm/dL 2+ Years 3.2 - 4.9 gm/dL Alcohol (ETOH) DXC 600 <0.005 (none detected) gm/dL > 0.300 Alkaline Phosphatase DXC 600 Both 0 - 4 Years 80 - 350 IU/L Both 5 Years - 9 Years 60 - 385 IU/L Both 10 Years - 13 Years 60 - 485 IU/L Male 14 Years - 18 Years 50 - 350 IU/L Female 14 Years - 18 Years 40 - 195 IU/L Both 19+ Years 32 - 91 IU/L ALT (SGPT) DXC 600 Male 17 - 63 IU/L Female 14 - 54 IU/L Ammonia DXC 600 9 - 35 uMOL/L > 100 Amylase DXC 600 28 - 100 U/L Anion Gap DXC 600 7 - 17 mmol/L AST (SGOT) DXC 600 0 Years - 4 Years 10 - 60 IU/L 5 Years - 9 Years 5 - 50 IU/L 10+ Years 15 - 41 IU/L Beta Hydroxybutyrate DXC 600 0.0 - 0.3 mmol/L BUN DXC 600 8 - 26 mg/dL > 100 BUN/Creatinine Ratio Calculation 15 - 25 Ratio Calcium DXC 600 0-2 days 6.2 - 11.0 mg/dL < 5.8, > 13.3 > 2 days 8.5 - 10.3 mg/dl < 6.3, > 13.3 Cardiac Risk Factor Calculation Male 1/2 Average 3.43 Average 4.97 2X Average 9.55 3X Average 23.99 Female 1/2 Average 3.27 Average 4.44 2X Average 7.05 3X Average 11.04 5/8/2018 pg. -

Hydrocephalus Patient Information Guide Experience Life Without Boundaries

Hydrocephalus Patient Information Guide Experience Life Without Boundaries Aesculap Neurosurgery 2 Table of Contents Foreword Page 4 About Us Page 5 What Is Hydrocephalus Page 6 Types Of Hydrocephalus Page 7 What You Should Know Page 8 Diagnosis Page 9 Treatment/Goal/Surgical Procedure Page 10 Complications Page 10 Prognosis/Helpful Sites Page 11 The Aesculap Shunts Page 12 Medical Definitions Page 13 3 Foreword The intention of this booklet is to provide information to patients, family members, caregivers and friends on the subject of hydrocephalus. The information provided is a general overview of the diagnosis and treatment of hydrocephalus and other conditions associated with hydrocephalus. About us History Aesculap AG (Germany) was founded in 1867 by Gottfried Jetter, a master craftsman trained in surgical instrument and cutlery techniques. Jetter’s original workshop, located in Tuttlingen, Germany, is the same location where Aesculap world headquarters resides today. The employee count has increased over the years (3,000+ employees), and the number of instrument patterns has grown from a select few to over 17,000; however, the German standard for quality and pattern consistency remains the same. Prior to 1977, many of the instruments sold in America by competing companies were sourced from Aesculap in Tuttlingen. In response to the United States customer demand for Aesculap quality surgical instruments, Aesculap, Inc. (U.S.) was established in 1977. Headquartered in Center Valley, Pennsylvania, with over one hundred direct nationwide sales representatives, Aesculap, Inc. currently supports the marketing, sales and distribution of Aesculap surgical instrumentation in the U.S. In order to support the company’s continued growth and provide the service and quality which customers have come to expect, Aesculap relocated the corporate offices from San Francisco to Center Valley, Pennsylvania. -

Basic Skills in Interpreting Laboratory Data, 5Th Edition

CHAPTER 1 DEFINITIONS AND CONCEPTS KAREN J. TIETZE This chapter is based, in part, on the second edition chapter titled “Definitions and Concepts,” which was written by Scott L. Traub. Objectives aboratory testing is used to detect disease, guide treatment, monitor response Lto treatment, and monitor disease progression. However, it is an imperfect sci ence. Laboratory testing may fail to identify abnormalities that are present (false After completing this chapter, negatives [FNs]) or identify abnormalities that are not present (false positives, the reader should be able to [FPs]). This chapter defines terms used to describe and differentiate laboratory • Differentiate between accuracy tests and describes factors that must be considered when assessing and applying and precision laboratory test results. • Distinguish between quantitative, qualitative, and semiqualitative DEFINITIONS laboratory tests Many terms are used to describe and differentiate laboratory test characteristics and • Define reference range and identify results. The clinician should recognize and understand these terms before assessing factors that affect a reference range and applying test results to individual patients. • Differentiate between sensitivity and Accuracy and Precision specificity, and calculate and assess Accuracy and precision are important laboratory quality control measures. Labora these parameters tories are expected to test analytes with accuracy and precision and to document the • Identify potential sources of quality control procedures. Accuracy of a quantitative assay is usually measured in laboratory errors and state the terms of an analytical performance, which includes accuracy and precision. Accuracy impact of these errors in the is defined as the extent to which the mean measurement is close to the true value.