Additions to Illustrated Manuscripts in Ottoman Workshops

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

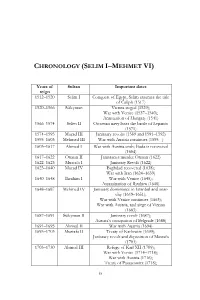

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

Experiencias De Intervención E Investigación: Buenas Prácticas, Alianzas Y Amenazas I Especialización En Patrimonio Cultural Sumergido Cohorte 2021

Experiencias de intervención e investigación: buenas prácticas, alianzas y amenazas I Especialización en Patrimonio Cultural Sumergido Cohorte 2021 Filipe Castro Bogotá, April 2021 2012-2014 Case Study 1 Gnalić Shipwreck (1569-1583) Jan Brueghel the Elder, 1595 The Gnalić ship was a large cargo ship built in Venice for the merchants Benedetto da Lezze, Piero Basadonna and Lazzaro Mocenigo. Suleiman I (1494-1566) Selim II (1524-1574 Murad III (1546-1595) Mehmed III (1566-1603) It was launched in 1569 and rated at 1,000 botti, a capacity equivalent to around 629 t, which corresponds to a length overall close to 40 m (Bondioli and Nicolardi 2012). Early in 1570, the Gnalić ship transported troops to Cyprus (which fell to the Ottomans in July). War of Cyprus (1570-1573): in spite of losing the Battle of Lepanto (Oct 7 1571), Sultan Selim II won Cyprus, a large ransom, and a part of Dalmatia. In 1571 the Gnalić ship fell into Ottoman hands. Sultan Selim II (1566-1574), son of Suleiman the Magnificent, expanded the Ottoman Empire and won the War of Cyprus (1570-1573). Giovanni Dionigi Galeni was born in Calabria, southern Italy, in 1519. In 1536 he was captured by one of Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha’s captains and engaged in the galleys as a slave. In 1541 Giovanni Galeni converted to Islam and became a corsair. His skills and leadership capacity eventually made him Bey of Algiers and later Grand Admiral in the Ottoman fleet, with the name Uluç Ali Reis. He died in 1587. In late July 1571 Uluç Ali encountered a large armed merchantman near Corfu: it was the Moceniga, Leze, & Basadonna, captained by Giovanni Tomaso Costanzo (1554-1581), a 16 years old Venetian condottiere (captain of a mercenary army), descendent from a famous 14th century condottiere named Iacomo Spadainfaccia Costanzo, and from Francesco Donato, who was Doge of Venice from 1545 to 1553. -

Festivities of Curfew Centralization and Mechanisms of Opposition in Ottoman Politics, 1582-1583

Venetians and Ottomans in the Early Modern Age Essays on Economic and Social Connected History edited by Anna Valerio Festivities of Curfew Centralization and Mechanisms of Opposition in Ottoman Politics, 1582-1583 Levent Kaya Ocakaçan (Bahçeşehir University, Turkey) Abstract The Ottoman Empire was a dynastic state, as were its counterparts in Europe and Asia in the early modern period. In order to explain the characteristics of this dynastic governance model, it is essential to focus on how the Ottoman ‘state’ mechanism functioned. One of the prominent aspects of the dynastic state was the integration of politics in household units. Direct or indirect connection of people to these households was the main condition of legitimacy. Thus, the redistribution and succession strategies had a centralized importance in dynastic states. Since being a member of the dynasty was a given category, the state could be reduced to the house of the dynasty at the micro levels. This house transcended those living in it, and in order to sustain the continuity of the house, there was a need to create a ritual showing ‘the loyalty to the dynastic household’. This loyalty was the dominant factor in ensuring the continuity of the house, in other words, the ‘state’, and therefore, the succession strategies in dynastic states had a key importance. Summary 1 Introduction. – 2 The Imperial Circumcision Festival of 1582, or Sultan Murad III’s Absolution Show. – 3 Şehzade Mehmed’s Provincial Posting Ceremony. – 4 Conclusion. Keywords Murad III. Mehmed III. Sehzade Mehmed. 16th century centralization. Ottoman house- hold system. Ottoman Empire. 1 Introduction Mehmed II, who represents the ‘centralization’ of the Ottoman Empire, legalized fratricide in order to sustain this continuity. -

Was Suleiman?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 9th Grade Suleiman Inquiry How “Magnificent” Was Suleiman? Titian, painting of Suleiman, c1530 ©World History Archive/Newscom Supporting Questions 1. How was Suleiman characterized during his reign? 2. How did Suleiman expand the Ottoman Empire? 3. What changes did Suleiman make to the governance of the Ottoman Empire? 4. To what extent did Suleiman promote tolerance in the Ottoman Empire? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 9th Grade Suleiman Inquiry How “Magnificent” Was Suleiman? 9.7 OTTOMANS AND MING PRE-1600: Christianity, Islam, and Neo-Confucianism influenced the New York State development of regions and shaped key centers of power in the world between 1368 and 1683. The Social Studies Ottoman Empire and Ming Dynasty were two powerful states, each with a view of itself and its place in the Framework Key world. Idea & Practices Gathering, Using, and Interpreting Evidence Comparison and Contextualization Staging the Students read an excerpt from the National Geographic (2014) article “After 450 Years, Archaeologists Still Question Hunting for Magnificent Sultan’s Heart.” Discuss what reasons might explain the fascination with finding Suleiman’s remains. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Supporting Question 4 How was Suleiman How did Suleiman expand What changes did Suleiman To what extent did Suleiman characterized during his the -

Mighty Guests of the Throne Note on Transliteration

Sultan Ahmed III’s calligraphy of the Basmala: “In the Name of God, the All-Merciful, the All-Compassionate” The Ottoman Sultans Mighty Guests of the Throne Note on Transliteration In this work, words in Ottoman Turkish, including the Turkish names of people and their written works, as well as place-names within the boundaries of present-day Turkey, have been transcribed according to official Turkish orthography. Accordingly, c is read as j, ç is ch, and ş is sh. The ğ is silent, but it lengthens the preceding vowel. I is pronounced like the “o” in “atom,” and ö is the same as the German letter in Köln or the French “eu” as in “peu.” Finally, ü is the same as the German letter in Düsseldorf or the French “u” in “lune.” The anglicized forms, however, are used for some well-known Turkish words, such as Turcoman, Seljuk, vizier, sheikh, and pasha as well as place-names, such as Anatolia, Gallipoli, and Rumelia. The Ottoman Sultans Mighty Guests of the Throne SALİH GÜLEN Translated by EMRAH ŞAHİN Copyright © 2010 by Blue Dome Press Originally published in Turkish as Tahtın Kudretli Misafirleri: Osmanlı Padişahları 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Published by Blue Dome Press 535 Fifth Avenue, 6th Fl New York, NY, 10017 www.bluedomepress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available ISBN 978-1-935295-04-4 Front cover: An 1867 painting of the Ottoman sultans from Osman Gazi to Sultan Abdülaziz by Stanislaw Chlebowski Front flap: Rosewater flask, encrusted with precious stones Title page: Ottoman Coat of Arms Back flap: Sultan Mehmed IV’s edict on the land grants that were deeded to the mosque erected by the Mother Sultan in Bahçekapı, Istanbul (Bottom: 16th century Ottoman parade helmet, encrusted with gems). -

'The Magnificent' & His Legacies

Suleiman I: ‘The Magnificent’ & His Legacies (part 1) Suleiman I: the “Magnificent” (1520-1566) … the “Magnificent” [From Tughra of Suleiman the Magnificent (additional readings) ] … “the Magnificent” - Tughra reflective of Suleiman’s wealth, power - “Suleiman shah ibn Selim shah khan al- muzzafar al-Daiman” : “Suleiman Shah son of Khan Selim, ever (the) victorious” - History reflected in use of ‘Khan’ for his father (‘khan’ from Mongol ‘leader’) - And ‘Shah’ for himself (Persian title ‘ruler’) … “the Magnificent” Like all Sultans, Suleiman struck his own coins. These are dated 1520; they carry the date of his inauguration. [from ‘Suleiman I http://members.aol.com/dkaplan888/sule.htm] … “the Magnificent” Suleimaniye Mosque: Testimony to “Magnificence” … “the Magnificent” Suleimaniye epitomized essence of Islam’s role in 16th century state: - Centre of education - medical training - religious scholarship - attached kitchen fed community, poor Recognized power of the Sultan (number of minarets), no subsequent buildings could obscure view of Mosque … “the Magnificent” Contemporary View of Mosque (from perspective of Golden Horn) … “the Magnificent” The Suleimaniye (looking down to Golden Horn): school with classrooms, ‘dormitory’ and courtyard to left … “the Magnificent” Architect Mimar Sinan: - born to simple stoneworker’s family - ‘enlisted’ into Janissary corps [note change in how one ‘became’ janissary] - trained as carpenter, became royal engineer - traveled throughout empire, brought together architectural styles Work epitomizes glory Suleiman gave to architecture, building during his reign … “the Magnificant” • Architect was Mimar Sinan (1490-1588): [see Minar Sinan in ‘Resources’] Photo from: http://www.allaboutturkey.com/si nan.htm … “the Magnificent” The Empire in 1566 Suleiman also known as the ‘Magnificent’ because the empire reached its geographical apex during his reign -- strong territorial advances in North Africa, central Europe (to walls of Vienna), Bessarabia and Iraq. -

A TRIBUTE to the KINGLY VIRTUES of SULTAN AHMED I (R

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Istanbul Sehir University Repository A TRIBUTE TO THE KINGLY VIRTUES OF SULTAN AHMED I (r. 1603- 1617): HOCAZÂDE ABDÜLAZİZ EFENDİ (d. 1618) AND HIS AHLÂK-I SULTÂN AHMEDÎ A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF İSTANBUL ŞEHİR UNIVERSITY BY SEMRA ÇÖREKÇİ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY SEPTEMBER 2012 ABSTRACT This thesis aims to offer a literary-historical analysis of Ahlâk-ı Sultân Ahmedî (Morals of Sultân Ahmed), an early seventeenth-century Ottoman treatise on ethics prepared for Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603-1617). This work of ethics was originally written in Persian in 1494-5 under the title, Ahlâk-ı Muhsinî (Morals of Muhsin), by Hüseyin Vâiz Kâşifî, a renowned Timurid scholar and intellectual. This work of ethics was dedicated to the Timurid ruler, Hüseyin Baykara (r. 1469-1506), but the main adressee was his son Ebu‘l-Muhsin Mirza. In around 1610, Ahmed I ordered a translation of this Persian work into Ottoman Turkish, a task which was completed, with some critical additions, in 1612 by Hocazâde Abdülaziz Efendi (d. 1618), the fourth son of the famous Hoca Sadeddin Efendi (d. 1599). Overall, this thesis is an attempt to provide a critical examination of Ahlâk-ı Sultân Ahmedî particularly with respect to the question of how such a translated book on ethics was used as a tool to create as well as to legitimize a powerful image of the Ottoman sultan at a time of crisis and change in the Ottoman imperial and dynastic establishment. -

Ottoman World ᇹᇺᇹ

THE OTTOMAN WORLD ᇹᇺᇹ Edited by Christine Woodhead First published by Routledge Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge Third Avenue, New York, NY Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © Christine Woodhead for selection and editorial matter; individual contributions, the contributors. The right of Christine Woodhead to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections and of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A catalog record for this book has been requested. ISBN: –––– (hbk) ISBN: –––– (ebk) Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by Swales & Willis Ltd, Exeter, Devon CONTENTS ᇹᇺᇹ List of illustrations viii List of maps ix List of tables ix List of contributors X Preface xiv Note on -

Beylerbeyi Palace

ENGLISH History Beylerbeyi means Grand Seigneur or The present Beylerbeyi Palace was designed Abdülhamid II and Beylerbeyi Palace Governor; the palace and the village were and built under the auspices of the Abdülhamid (1842-1918) ruled the expected from the Western powers named after Beylerbeyi Mehmet Pasha, architects Sarkis Balyan and Agop Balyan BEYLERBeyİ Governor of Rumeli in the reign of Sultan between 1861 and 1865 on the orders of Ottoman Empire from 1876 to without their intrusion into Murad III in the late 16th century. Mehmet Sultan Abdülaziz. 1909. Under his autocratic Ottoman affairs. Subsequently, Pasha built a mansion on this site at that rule, the reform movement he dismissed the Parliament Today Beylerbeyi Palace serves as a palace time, and though it eventually vanished, the of Tanzimat (Reorganization) and suspended the constitution. PALACE museum linked to the National Palaces. name Beylerbeyi lived on. reached its climax and he For the next 30 years, he ruled Located on the Asian shore of the Bosphorus, this splendid adopted a policy of pan- from his seclusion at summer palace is a reflection of the sultan’s interest in The first Beylerbeyi Palace was wooden Islamism in opposition to Yıldız Palace. and was built for Sultan Mahmud II in early western styles of architecture. 19th century. Later the original palace was Western intervention in In 1909, he was deposed shortly abandoned following a fire in the reign of Ottoman affairs. after the Young Turk Revolution, Sultan Abdülaziz built this beautiful 19th of Austria, Shah Nasireddin of Persia, Reza Sultan Abdülmecid. He promulgated the first Ottoman and his brother Mehmed V was century palace on the Asian shore of the Shah Pahlavi, Tsar Nicholas II, and King constitution in 1876, primarily to ward proclaimed as sultan. -

The Urbanization and Ottomanization of the Halvetiye Sufi Order by the City of Amasya in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

The City as a Historical Actor: The Urbanization and Ottomanization of the Halvetiye Sufi Order by the City of Amasya in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries By Hasan Karatas A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Hamid Algar, Chair Professor Leslie Peirce Professor Beshara Doumani Professor Wali Ahmadi Spring 2011 The City as a Historical Actor: The Urbanization and Ottomanization of the Halvetiye Sufi Order by the City of Amasya in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries ©2011 by Hasan Karatas Abstract The City as a Historical Actor: The Urbanization and Ottomanization of the Halvetiye Sufi Order by the City of Amasya in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries by Hasan Karatas Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Hamid Algar, Chair This dissertation argues for the historical agency of the North Anatolian city of Amasya through an analysis of the social and political history of Islamic mysticism in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Ottoman Empire. The story of the transmission of the Halvetiye Sufi order from geographical and political margins to the imperial center in both ideological and physical sense underlines Amasya’s contribution to the making of the socio-religious scene of the Ottoman capital at its formative stages. The city exerted its agency as it urbanized, “Ottomanized” and catapulted marginalized Halvetiye Sufi order to Istanbul where the Ottoman socio-religious fabric was in the making. This study constitutes one of the first broad-ranging histories of an Ottoman Sufi order, as a social group shaped by regional networks of politics and patronage in the formative fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. -

![Haseki Sultan Waqf Complex…’, Resources ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6297/haseki-sultan-waqf-complex-resources-3336297.webp)

Haseki Sultan Waqf Complex…’, Resources ]

Part 1: Early Islamic to Pre-colonial era Week 3: The Ottomans (15th-16th centuries) Emergence of Ottoman Empire “ISLAM: EMPIRE OF FAITH” Episode -- ‘The Ottomans’: rise of empire up to and including the reign of ‘Suleiman the Magnificent’ [excerpts shown in class] Emergence of Ottoman Empire Ottoman ‘Empire’: 14th Century (1350) Ottoman ‘Empire’: 15th Century (1451) Emergence of the Ottoman Empire Emergence of Ottoman Empire timurid1405 Mamluks: c. 1400 Mamluks • “Mamluk” meaning ‘owned’: • slaves taken by rulers Middle East &North Africa • trained as soldiers for armies, administration • widely used Mamluks - 13th Century Egypt: Mamluks replaced Sultan: - leader ‘Baybars’ married Sultan’s wife - brought uncle of former Sultan from Baghdad to Cairo (1260) - established Caliphate - Caliphate did not last long in Cairo but power in region remained in Mamluk hands Mamluks - 1517: conquered by Ottomans (Selim I): - Mamluks left in control of administration - ‘province’ of Ottomans - Continued to support administration through incorporating slaves - Re-emerged as ‘semi-autonomous in 19th century Emergence of Harem: 14th Century • ‘Era of Osman’: • marriage strategic, crossed tribal and religious lines • high degree of symbiosis religious conversions [both Christian and Muslim] • sharing of traditions, ideas, institutions • Nomadic, warrior ideologies ‘Frontier Society’ • [see ‘Document: Ibn Battuta’ in Additional Reading] Emergence of Harem: 14th century • Story of Melik Danismend (Turkish), Artuhi (Armenian) and Efromiya (Greek woman) : • -

Tribal Banditry in Ottoman Ayntab (1690-1730)

TRIBAL BANDITRY IN OTTOMAN AYNTAB (1690-1730) A Master’s Thesis by MUHSİN SOYUDOĞAN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2005 To My Mother TRIBAL BANDITRY IN OTTOMAN AYNTAB (1690-1730) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by MUHSİN SOYUDOĞAN In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2005 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. --------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Oktay Özel Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. --------------------------------- Asst. Prof. Evgeni Radushev Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. --------------------------------- Prof. Dr. Mehmet Öz Examining Committee Member Approval of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences --------------------------------- Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT Tribal Banditry in Ottoman Ayntab (1690-1730) Soyudoğan, Muhsin. M.A., Department of History. Supervisior: Asst. Prof. Oktay Özel. This thesis attempts to understand the tribal banditry through a micro historical analsysis, which focuses on the tribal banditry in Ayntab region during the late seveneteenth and early eighteenth century. Though it focuses on a specific region, it tries to contribute to the discussion on banditry and also tries to develop a model for analyzing banditry in the Ottoman Empire.