A Study of Muslim Economic Thinking in the 11Th A.H. / 17Th C.E. Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

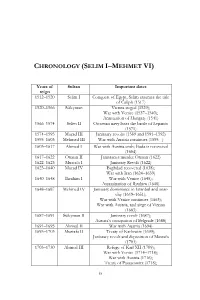

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

The Transcultural Critic: Sabahattin Ali and Beyond

m Mittelpunkt dieses Bandes steht das Werk des türkischen Autors und Übersetzers aus dem Deutschen Sabahattin Ali, der mit seinem Roman KürkI Mantolu Madonna (Die Madonna im Pelzmantel) zu posthumem Ruhm gelangte. Der Roman, der zum Großteil in Deutschland spielt, und andere seiner Werke werden unter Aspekten der Weltliteratur, (kultureller) Übersetzung und Intertextualität diskutiert. Damit reicht der Fokus weit über die bislang im Vordergrund stehende interkulturelle Liebesgeschichte 2016 Türkisch-Deutsche Studien in der Madonna hinaus. Weitere Beiträge beschäftigen sich mit Zafer Şenocaks Essaysammlung Jahrbuch 2016 Deutschsein und dem transkulturellen Lernen mit Bilderbüchern. Ein Interview mit Selim Özdoğan rundet diese Ausgabe ab. The Transcultural Critic: Sabahattin Ali and Beyond herausgegeben von Şeyda Ozil, Michael Hofmann, Jens-Peter Laut, Yasemin Dayıoğlu-Yücel, Cornelia Zierau und Kristin Dickinson Türkisch-deutsche Studien. Jahrbuch ISBN: 978-3-86395-297-6 Universitätsverlag Göttingen ISSN: 2198-5286 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Şeyda Ozil, Michael Hofmann, Jens-Peter Laut, Yasemin Dayıoğlu-Yücel, Cornelia Zierau, Kristin Dickinson (Hg.) The Transcultural Critic: Sabahattin Ali and Beyond This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Türkisch-deutsche Studien. Jahrbuch 2016 erschienen im Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2017 The Transcultural Critic: Sabahattin Ali and Beyond Herausgegeben von Şeyda Ozil, Michael Hofmann, Jens-Peter Laut, Yasemin Dayıoğlu-Yücel, Cornelia Zierau und Kristin Dickinson in Zusammenarbeit mit Didem Uca Türkisch-deutsche Studien. Jahrbuch 2016 Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2017 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.dnb.de> abrufbar. Türkisch-deutsche Studien. Jahrbuch herausgegeben von Prof. Dr. -

A Chapter in the History of Coffee: a Critical Edition and Translation of Murtad}A> Az-Zabīdī's Epistle on Coffee

A Chapter in the History of Coffee: A Critical Edition and Translation of Murtad}a> az-Zabīdī’s Epistle on Coffee Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Heather Marie Sweetser, B.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2012 Thesis Committee: Dr. Georges Tamer, Advisor Dr. Joseph Zeidan Copyright by Heather Marie Sweetser 2012 Abstract What follows is an edition and translation of an Arabic manuscript written by Murtad}a> az-Zabīdī in 1171/1758 in defense of coffee as per Islamic legality. He cites the main objections to coffee drinking and refutes them systematically using examples from Islamic jurisprudence to back up his points. The author also includes lines of poetry in his epistle in order to defend coffee’s legality. This particular manuscript is important due to its illustrious author as well as to its content, as few documents describing the legal issues surrounding coffee at such a late date have been properly explored by coffee historians. The dictionary Ta>j al-ʿAru>s, authored by Murtad}a> az-Zabīdī himself, as well as Edward Lane’s dictionary, were used to translate the manuscript, which was first edited. Unfortunately, I was only able to acquire one complete and one incomplete manuscript; other known manuscripts were unavailable. Arabic mistakes in the original have been corrected and the translation is annotated to provide appropriate background to the epistle’s commentary. A brief introduction to the history of coffee, a sample of the debate surrounding the legality of coffee in Islam, and a biography of the author is provided. -

Animal Welfare and the Protection of Draft Animals in the Ottoman Fatwa¯ Literature and Legislation

religions Article Be Gentle to Them: Animal Welfare and the Protection of Draft Animals in the Ottoman Fatwa¯ Literature and Legislation Necmettin Kızılkaya Faculty of Divinity, Istanbul University, 34452 Istanbul,˙ Turkey; [email protected] Received: 5 August 2020; Accepted: 16 October 2020; Published: 20 October 2020 Abstract: Animal studies in the Islamic context have greatly increased in number in recent years. These studies mostly examine the subject of animal treatment through the two main sources of Islam, namely, the Qur’an and the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad. Some studies that go beyond these two sources examine the subject of animal treatment through the texts of various disciplines, especially those of Islamic jurisprudence and law. Although these two research approaches offer a picture of how animal treatment is perceived in Islamic civilization, it is still not a full one. Other sources, such as fatwa¯ books and archive documents, should be used to fill in the gaps. By incorporating these into the pool of research, we will be better enabled to understand how the principles expressed in the main sources of Islam are reflected in daily life. In this article, I shall examine animal welfare and ( animal protection in the Ottoman context based on the fataw¯ a¯ of Shaykh al-Islam¯ Ebu’s-Su¯ ud¯ Efendi and archival documents. Keywords: animal welfare; animal protection; draft animals; Ottoman Legislation; Fatwa;¯ Ebussuud¯ Efendi In addition to the foundational sources of Islam and the main texts of various disciplines, the use of fatwa¯ (plural: fataw¯ a¯) collections and archival documents will shed light on an accurate understanding of Muslim societies’ perspectives on animals. -

I TREATING OUTLAWS and REGISTERING MISCREANTS IN

TREATING OUTLAWS AND REGISTERING MISCREANTS IN EARLY MODERN OTTOMAN SOCIETY: A STUDY ON THE LEGAL DIAGNOSIS OF DEVIANCE IN ŞEYHÜLİSLAM FATWAS by EMİNE EKİN TUŞALP Submitted to the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University Spring 2005 i TREATING OUTLAWS AND REGISTERING MISCREANTS IN EARLY MODERN OTTOMAN SOCIETY: A STUDY ON THE LEGAL DIAGNOSIS OF DEVIANCE IN ŞEYHÜLİSLAM FATWAS APPROVED BY: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tülay Artan (Thesis Supervisor) ………………………… Ass. Prof. Dr. Akşin Somel ………………………… Ass. Prof. Dr. Dicle Koğacıoğlu ………………………… Prof. Dr. Ahmet Alkan (Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences) ………………………… Prof. Dr. Nakiye Boyacıgiller (Director of the Institute of Social Sciences) ………………………… DATE OF APPROVAL: 17/06/2005 ii © EMİNE EKİN TUŞALP ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT TREATING OUTLAWS AND REGISTERING MISCREANTS IN EARLY MODERN OTTOMAN SOCIETY: A STUDY ON THE LEGAL DIAGNOSIS OF DEVIANCE IN ŞEYHÜLİSLAM FATWAS Emine Ekin Tuşalp M.A., History Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tülay Artan June 2005, ix + 115 pages This work investigates the forms of deviance rampant in early modern Ottoman society and their legal treatment, according to the fatwas issued by the Ottoman şeyhülislams in the 17th and 18th centuries. One of the aims of this thesis is to present different behavioural forms found in the şeyhülislam fatwas that ranged from simple social malevolencies to acts which were regarded as heresy. In the end of our analysis, the significance of the fatwa literature for Ottoman social history will once more be emphasized. On the other hand, it will be argued that as a legal forum, the fetvahane was not merely a consultative and ancillary office, but a centre that fabricated the legal and moral devices/discourses employed to direct and stem the social tendencies in the Ottoman society. -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

The Conversion of the Jews and the Islamization of Jewish Spaces During the First Centuries of the Ottoman Empire’

BAHAR, Beki L. ‘The conversion of the Jews and the islamization of Jewish spaces during the first centuries of the Ottoman empire’. Jewish Migration: Voices of the Diaspora. Raniero Speelman, Monica Jansen & Silvia Gaiga eds. ITALIANISTICA ULTRAIECTINA 7. Utrecht : Igitur Publishing, 2012. ISBN 978‐90‐6701‐032‐0. SUMMARY This essay by the late Beki L. Behar (z.l.) focuses on conversion to Islam until the end of the Seventeenth Century. If we can speak of a privileged treatment of the Jews in the reigns of Mehmet Fatih, Bayezit II, Süleyman and Selim II – the period of Gracia Mendez and Josef Nasi –, Mehmet IV’s reign (1648‐1687) was marked by lack of tolerance and the Islamic fanatism of the fundamentalist Kadezadeli sect, in which period Jews had to face all sorts of prohibition and forced conversion, sometimes losing their living quarters. Although the Jews as inhabitants of cities rather than villages were generally not subjected to conversion and were not encouraged to enter upon the career at Court known as devşirme, an important wave of conversions initiated with Shabtai Zwi (Sabbatai Zevi), the false mashiah who preferred Islam to death penalty. His numerous followers are known in Turkish as dönmeler (dönmes). Other conversions had a less dramatic background, such as divorcing under Shari’a law or for convenience’s sake. A famous case is the court fysician Moshe ben Raphael Abravanel, who became Muslim in order to be able to practise. KEYWORDS Conversion, Shabtai Zwi, dönmes, Islamization The authors The proceedings of the international conference Jewish Migration: Voices of the Diaspora (Istanbul, June 23‐27 2010) are volume 7 of the series ITALIANISTICA ULTRAIECTINA. -

A Study of Muslim Economic Thinking in the 11Th A.H

Munich Personal RePEc Archive A study of Muslim economic thinking in the 11th A.H. / 17th C.E. century Islahi, Abdul Azim Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75431/ MPRA Paper No. 75431, posted 06 Dec 2016 02:55 UTC Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Research Center King Abdulaziz University Scientific Publising Centre King Abdulaziz University P.O. Box 80200, Jeddah, 21589 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia FOREWORD There are numerous works on the history of Islamic economic thought. But almost all researches come to an end in 9th AH/15th CE century. We hardly find a reference to the economic ideas of Muslim scholars who lived in the 16th or 17th century, in works dealing with the history of Islamic economic thought. The period after the 9th/15th century remained largely unexplored. Dr. Islahi has ventured to investigate the periods after the 9th/15th century. He has already completed a study on Muslim economic thinking and institutions in the 10th/16th century (2009). In the mean time, he carried out the study on Muslim economic thinking during the 11th/17th century, which is now in your hand. As the author would like to note, it is only a sketch of the economic ideas in the period under study and a research initiative. It covers the sources available in Arabic, with a focus on the heartland of Islam. There is a need to explore Muslim economic ideas in works written in Persian, Turkish and other languages, as the importance of these languages increased in later periods. -

Download the PDF File

This study focuses on the role of the Mirage in the Sands: Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa, the Ottoman Special Organization (SO), in the Sinai-Palestine The Ottoman Special front during the First World War. The Organization on the SO was defined by its use of various tactics of unconventional warfare, namely Sinai-Palestine Front intelligence-gathering, espionage, guerilla Polat Safi warfare, and propaganda. Along the Sinai- Palestine front, the operational goal to which these tactics were put to use was to bring about an uprising in British-occupied Egypt.1 The SO hoped to secure the support of the tribal and Bedouin populations of Sinai-Palestine front and the people of Egypt and encourage them to rise up against the British rule.2 The SO’s involvement on the Sinai- Palestine front was part of a broader effort developed between Germany and the Ottoman State for the purposes of encircling Egypt. An examination of the SO’s work in Palestine will illuminate the nature of the peripheral strategy the Germans and Ottomans employed outside of Europe during World War I and how it was applied in practice. As part of this broader strategy, in Palestine the SO engaged in a volunteer recruitment campaign, worked to foment rebellion behind enemy lines, engaged in guerilla warfare, and carried out intelligence duties. By examining the nature and contours of the SO’s operations there, this study aims to provide both new insights into the regional aspects of a crucial organization and also valuable information which will offer a firmer ground for future comparative studies on the different operational bases of the SO. -

(Self) Fashioning of an Ottoman Christian Prince

Amanda Danielle Giammanco (SELF) FASHIONING OF AN OTTOMAN CHRISTIAN PRINCE: JACHIA IBN MEHMED IN CONFESSIONAL DIPLOMACY OF THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MA Thesis in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Central European University Budapest CEU eTD Collection May 2015 (SELF) FASHIONING OF AN OTTOMAN CHRISTIAN PRINCE: JACHIA IBN MEHMED IN CONFESSIONAL DIPLOMACY OF THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY by Amanda Danielle Giammanco (United States of America) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest May 2015 (SELF) FASHIONING OF AN OTTOMAN CHRISTIAN PRINCE: JACHIA IBN MEHMED IN CONFESSIONAL DIPLOMACY OF THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY by Amanda Danielle Giammanco (United States of America) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards -

Habsburg–Ottoman Communication in the Mid-17Th Century – the Death of Imperial Courier Johann Dietz

Habsburg–Ottoman Communication in the Mid-17th Century – The Death of Imperial Courier Johann Dietz. A Case Study János Szabados* 17. Yüzyılın Ortasında Osmanlı-Habsburg Muhaberatları: İmparatorluk Ulağı Johann Dietz’in Vefatı ve Doğurduğu Sonuçlar Öz Zitvatorok Anlaşması’nın (1606) ardından Habsburg Monarşisi’nin şark diploma- sisi İmparatorluk Askeri Konseyi (Hofkriegsrat) tarafından idare edildi. Bu dönemde ulaklar son derece ehemmiyetli vazifeler üstlendiklerinden, Viyana Paktı’yla (1615) güvenliklerinin her iki tarafın resmi ulaklarını da kapsayacak şekilde genişletilmesi emredildi. Bu anlaşmaya rağmen, ulaklar, yolculukları sırasında sayısız olayla başa çıkmak zorunda kaldı. Johannes Dietz vakası da bu gibi hadiselere bir örnek teşkil etmektedir. Dietz, Konstantinopolis’e bir takım belgeleri teslim etmek için gönderildi. 1651 Kasım ayında Macar haydukları tarafından saldırıya uğradı; kolundan vuruldu ve aldığı yaralar neticesinde öldü. Fakat ölmeden evvel başına gelenleri kağıda döktü. Ayrıca bu çatışmayı teyit eden başka kaynaklar da bulunmaktadır. Örneğin Buda’da gizli yazışmaları yapan kişinin, (mahlası Hans Caspar idi) ulağın vefatıyla ilgili malumatları içeren mektubu bunlardan biridir. Habsburg elçisinin (Simon Reniger) bir Osmanlı ulağı tarafından Dietz vakası hakkında gayri resmi yollardan bilgilendirildiği sırada, olayın Kutsal Roma İmparatorluğu’nun gazetelerinde basılması da enformasyon akışı bağlamında değerlendirildiğinde oldukça ilginçtir. Suçlayıcı bir takım bilgiler ve Paşa’nın emriyle gerçekleşen akınlar hakkında şikayetler içeren mektupları daha da ileriye göndermek hiçbir suretle Buda vezirinin (Murad Paşa) çıkarlarına hizmet etmiyordu. Sonuç olarak başka bir ulak gerekiyordu. Bu ulak da 18 Ocak 1652 tarihinde Konstantinopolis’e varışından önce, kısa bir süreliğine Paşa tarafından alıkonuldu. Mektupların Konstantinopolis’e ulaşabilmesi için kral naibi (palatin Pál Pálffy), onları Erdel Prensliği üzerinden gönderdi. En nihayet * University of Szeged. -

Experiencias De Intervención E Investigación: Buenas Prácticas, Alianzas Y Amenazas I Especialización En Patrimonio Cultural Sumergido Cohorte 2021

Experiencias de intervención e investigación: buenas prácticas, alianzas y amenazas I Especialización en Patrimonio Cultural Sumergido Cohorte 2021 Filipe Castro Bogotá, April 2021 2012-2014 Case Study 1 Gnalić Shipwreck (1569-1583) Jan Brueghel the Elder, 1595 The Gnalić ship was a large cargo ship built in Venice for the merchants Benedetto da Lezze, Piero Basadonna and Lazzaro Mocenigo. Suleiman I (1494-1566) Selim II (1524-1574 Murad III (1546-1595) Mehmed III (1566-1603) It was launched in 1569 and rated at 1,000 botti, a capacity equivalent to around 629 t, which corresponds to a length overall close to 40 m (Bondioli and Nicolardi 2012). Early in 1570, the Gnalić ship transported troops to Cyprus (which fell to the Ottomans in July). War of Cyprus (1570-1573): in spite of losing the Battle of Lepanto (Oct 7 1571), Sultan Selim II won Cyprus, a large ransom, and a part of Dalmatia. In 1571 the Gnalić ship fell into Ottoman hands. Sultan Selim II (1566-1574), son of Suleiman the Magnificent, expanded the Ottoman Empire and won the War of Cyprus (1570-1573). Giovanni Dionigi Galeni was born in Calabria, southern Italy, in 1519. In 1536 he was captured by one of Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha’s captains and engaged in the galleys as a slave. In 1541 Giovanni Galeni converted to Islam and became a corsair. His skills and leadership capacity eventually made him Bey of Algiers and later Grand Admiral in the Ottoman fleet, with the name Uluç Ali Reis. He died in 1587. In late July 1571 Uluç Ali encountered a large armed merchantman near Corfu: it was the Moceniga, Leze, & Basadonna, captained by Giovanni Tomaso Costanzo (1554-1581), a 16 years old Venetian condottiere (captain of a mercenary army), descendent from a famous 14th century condottiere named Iacomo Spadainfaccia Costanzo, and from Francesco Donato, who was Doge of Venice from 1545 to 1553.