Anglo-French Relations in Syria: from Entente Cordiale to Sykes-Picot a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the College of Arts A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Iraq and Syria

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2017 The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria Zachary Kielp Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kielp, Zachary, "The Unraveling of the Nation-State in the Middle East: Examples of Iraq and Syria" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3225. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3225 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Zachary Kielp December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Zachary Kielp ii THE UNRAVELING OF THE NATION-STATE IN THE MIDDLE EAST: EXAMPLES OF IRAQ AND SYRIA Defense and Strategic Studies Missouri State University, December 2017 Master of Science Zachary Kielp ABSTRACT After the carnage of World War One and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire a new form of political organization was brought to the Middle East, the Nation-State. -

World War I Concept Learning Outline Objectives

AP European History: Period 4.1 Teacher’s Edition World War I Concept Learning Outline Objectives I. Long-term causes of World War I 4.1.I.A INT-9 A. Rival alliances: Triple Alliance vs. Triple Entente SP-6/17/18 1. 1871: The balance of power of Europe was upset by the decisive Prussian victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the creation of the German Empire. a. Bismarck thereafter feared French revenge and negotiated treaties to isolate France. b. Bismarck also feared Russia, especially after the Congress of Berlin in 1878 when Russia blamed Germany for not gaining territory in the Balkans. 2. In 1879, the Dual Alliance emerged: Germany and Austria a. Bismarck sought to thwart Russian expansion. b. The Dual Alliance was based on German support for Austria in its struggle with Russia over expansion in the Balkans. c. This became a major feature of European diplomacy until the end of World War I. 3. Triple Alliance, 1881: Italy joined Germany and Austria Italy sought support for its imperialistic ambitions in the Mediterranean and Africa. 4. Russian-German Reinsurance Treaty, 1887 a. It promised the neutrality of both Germany and Russia if either country went to war with another country. b. Kaiser Wilhelm II refused to renew the reinsurance treaty after removing Bismarck in 1890. This can be seen as a huge diplomatic blunder; Russia wanted to renew it but now had no assurances it was safe from a German invasion. France courted Russia; the two became allies. Germany, now out of necessity, developed closer ties to Austria. -

The 1904 Anglo-French Newfoundland Fisheries Convention: Another Look

RESEARCH NOTES/NOTES DE RECHERCHE The 1904 Anglo-French Newfoundland Fisheries Convention: Another Look THE EXISTING LITERATURE ON ANGLO-FRENCH RELATIONS at the turn of the century, as well as that which specifically addresses the 1904 entente cordiale, for the most part makes only passing mention of the Newfoundland fisheries issue. Understandably, the focus of these accounts tends to be on the changing relations between the great powers, and on the most important aspect of the entente itself, which was the definition of boundaries and spheres of influence in North and West Africa. The exceptions are P.J.V. Rolo's study of the entente, which does recognize the crucial place of the fisheries issue in the context of the overall negotiation, and F.F. Thompson's brief account of the Newfoundland settlement from a colonial perspective in his standard work on the French, or Treaty, Shore question. i This note expands these accounts of the evolution of the 1904 Anglo-French Fisheries Convention, reinforces the view that it was vital to the successful completion of the overall package, and looks at the aftermath. This is not the place to discuss in detail the reasons for Anglo-French rapprochement which culminated in the 1904 entente cordiale. At the risk of oversimplification, one can point to several key factors. The Fashoda incident (1898) demonstrated, in time, to many French politicians that there was no hope of ending the resented British occupation of Egypt and the Nile valley. Confrontation with Britain in Africa was clearly futile, and accommodation potentially advantageous. Increasingly, the parti colonial urged the French government to consider giving up its financial and economic influence in Egypt, recognizing British predominance there, in return for British acceptance of France's ambition to establish a protectorate over Morocco and concessions elsewhere.2 Once this reasoning had been accepted and advanced by the French government, the British government eventually proved willing to respond positively (if carefully). -

Nationalism in Ottoman Greater Syria 1840-1914 the Divisive Legacy of Sectarianism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2008-12 Nationalism in Ottoman Greater Syria 1840-1914 the divisive legacy of Sectarianism Francioch, Gregory A. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/3850 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS NATIONALISM IN OTTOMAN GREATER SYRIA 1840- 1914: THE DIVISIVE LEGACY OF SECTARIANISM by Gregory A. Francioch December 2008 Thesis Advisor: Anne Marie Baylouny Second Reader: Boris Keyser Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2008 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Nationalism in Ottoman Greater Syria 1840- 5. FUNDING NUMBERS 1914: The Divisive Legacy of Sectarianism 6. AUTHOR(S) Greg Francioch 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. -

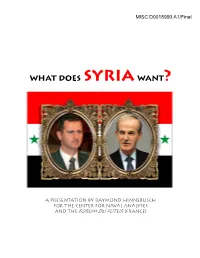

What Does Syria Want?

What Does Syria Want? A Presentation by Raymond Hinnebusch for the Center for Naval Analyses and the ForumForum dudu FuturFutur (france) 1 A Presentation by Raymond Hinnebusch for the Center for Naval Analyses and the Forum Du Futur (France) The distinguished American academic Raymond Hinnebusch, Director of the Centre for Syrian Studies and Professor of International Relations and Middle East Politics at the University of St. Andrews (UK), recently spoke at a France/U.S. dialogue in Paris co-sponsored by CNA and the Forum du Futur. Dr. Hinnebusch agreed to update his very thoughtful and salient presentation, “What Does Syria Want?” so that we might make it avail- able to a wider audience. The views expressed are his own and constitute an assessment of Syrian strategic think- ing. Raymond Hinnebusch may be contacted via e-mail at: [email protected] (Shown on the cover): A double portrait of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (left) and his father (right), Hafez al-Assad, who was President of Syria from 1971-2000. 2 What Does Syria Want? the country and ideology of the ruling Ba’th party, is a direct consequence of this experience. By Raymond Hinnebusch Centre for Syrian Studies, “Syria is imbued with a powerful sense University of St. Andrews, (UK) of grievance from the history of its formation as a state.” With French President Nicholas Sarkozy’s invitation of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to Paris in July, More than that, from its long disillusioning experience 2008, the question of whether Syria is “serious” about with the West, Syria has a profoundly jaundiced view changing its ways and entitled to rehabilitation by the of contemporary international order, recently much re- international community, has become a matter of some inforced, which it sees as replete with double standards. -

CAUSES of WORLD WAR I Objective: Analyze the Causes of World War I

CAUSES of WORLD WAR I Objective: Analyze the causes of World War I. Do Now: What are some holidays during which people celebrate pride in their national heritage? Causes of World War I - MANIA M ilitarism – policy of building up strong military forces to prepare for war Alliances - agreements between nations to aid and protect one another ationalism – pride in or devotion to one’s Ncountry I mperialism – when one country takes over another country economically and politically Assassination – murder of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand Causes of WWI - Militarism Total Defense Expenditures for the Great Powers [Ger., A-H, It., Fr., Br., Rus.] in millions of £s (British pounds). 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1914 94 130 154 268 289 398 1910-1914 Increase in Defense Expenditures France 10% Britain 13% Russia 39% Germany 73% Causes of WWI - Alliances Triple Entente: Triple Alliance: Great Britain Germany France Austria-Hungary Russia Italy Causes of WWI - Nationalism Causes of WWI - Nationalism Pan-Germanism - movement to unify the people of all German speaking countries Germanic Countries Austria * Luxembourg Belgium Netherlands Denmark Norway Iceland Sweden Germany * Switzerland * Liechtenstein United * Kingdom * = German speaking country Causes of WWI - Nationalism Pan-Slavism - movement to unify all of the Slavic people Imperialism: European conquest of Africa Causes of WWI - Imperialism Causes of WWI - Imperialism The “Spark” Causes of WWI - Assassination Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand visited the city of Sarajevo in Bosnia – a country that was under the control of Austria. Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Duchess Sophie in Sarajevo, Bosnia, on June 28th, 1914. Causes of WWI - Assassination Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife were killed in Bosnia by a Serbian nationalist who believed that Bosnia should belong to Serbia. -

MIDDLE EAST, NORTH AFRICA China, Russia and Iran Seek to Revive Syrian Railways

MIDDLE EAST, NORTH AFRICA China, Russia and Iran Seek to Revive Syrian Railways OE Watch Commentary: In late November, the Syrian Ministry of Transport announced a major “…China’s ownership of railways lines, in addition to its signing plan to repair, update and expand Syria’s railway of a 2017 agreement with Syria to use the Lattakia Port and system. As detailed in the accompanying excerpt from the Syrian government daily al-Thawra, the maritime transport means that China will own the country…” plan includes completing an earlier project to connect Deir ez-Zor and Albu Kamal, along the border with Iraq’s al-Anbar Province. It also calls for a new line across the Syrian desert, connecting Homs to Deir ez-Zor. Along with helping jump-start the domestic economy, an effective rail network would allow Syria to leverage is strategic location, at the crossroads of historical east-west and north-south trade routes. The accompanying passage from the Syrian opposition news source Enab Baladi highlights the importance of Chinese investment to Syrian reconstruction efforts in general and the railway sector in particular. It cites a Syrian researcher who hints at extensive Chinese involvement in the future ownership of the Syrian rail system, something that, combined with a 2017 agreement allowing China to use the Lattakia Port, means that China will “own the country.” Russia is also involved in revamping the Syrian rail network, and the article notes that Russia’s UralVagonZavod will be providing new railway cars to Syria starting next year. Syria’s planned railroad extension along the Euphrates from Deir ez-Zor to the Iraqi border dates from before the war. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99q9f2k0 Author Bailony, Reem Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Reem Bailony 2015 © Copyright by Reem Bailony 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 by Reem Bailony Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor James L. Gelvin, Chair This dissertation explores the transnational dimensions of the Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927. By including the activities of Syrian migrants in Egypt, Europe and the Americas, this study moves away from state-centric histories of the anti-French rebellion. Though they lived far away from the battlefields of Syria and Lebanon, migrants championed, contested, debated, and imagined the rebellion from all corners of the mahjar (or diaspora). Skeptics and supporters organized petition campaigns, solicited financial aid for rebels and civilians alike, and partook in various meetings and conferences abroad. Syrians abroad also clandestinely coordinated with rebel leaders for the transfer of weapons and funds, as well as offered strategic advice based on the political climates in Paris and Geneva. Moreover, key émigré figures played a significant role in defining the revolt, determining its goals, and formulating its program. By situating the revolt in the broader internationalism of the 1920s, this study brings to life the hitherto neglected role migrants played in bridging the local and global, the national and international. -

Aachen, 590,672

INDEX THIS Index contains no reference to the Introductory Tables which pre· sent a summary of the Finance and Commerce of the United Kingdom, British India, the British Colonies, the various countries of Europe, the United States of America, and Japan. AAC AFR ACHEN, 590,672 Adrar, 815, 1041 A Aalborg, 491 Adrianople (town), 1097 Aalesund, 1062 - (Vilayet), 1096 Aargau, 1078, 1080 Adua, 337 Aarhus, 491 Adulis Bay, 569 Abaco (Bahamas), 244 lEtolia, 705 Abbas Hilmi, Khedive, 1122 Afghanistan, area, 339 Abdul-Hamid n., 1091 - army, 340 Abdur Rahman Khan, 339 - books of reference, 342 Abeokuta (W. Africa), 219 - currency, 342 Abercorn (Cent. Africa), 215 - exports, 342 Aberdeen, 22; University, 34 - government, 340 Aberystwith College, 34 - horticulture, 341 Abo (Finland), 933, 985 - imports, 342 Abomey, 572 - justice, 340 Abruzzi, 732 -land cultivation, 341 Abyssinia, 337 - manufactures, 341 Abyssinian Church, 337, 1127 - mining, 341 Ahuna (Coptic), 337 - origin of the Afghans, 339 Acajutla (Salvador), 998 - population, 340 Acanceh (Mexico), 799 - reigning sovereign, 339 Acarnania, 705 - revenue, 340 Accra, 218 - trade, 341 Achaia, 705 - trade routes, 341 .Achikulak, 933 Africa, Central, Protectorate, 193 Acklin's Island, 244 East (British), 194 Aconcagua, 4.46 -- (German), 623 Acre (Bolivia), 430, 431, 437 -- - Italian, 768 Adamawa, 211 -- Portuguese, 909 Adana (town), 1097 -- South-West (German), 622 - (Vilayet), 1096 - (Turkish), 1095, 1097 Adelaide, 297 ; University, 298 - West (British), 218 Aden, 108, 129 -- (French), 569 Adis Ababa, 337, 769 -- German, 621, 622 Admiralty Island (W. Pacific), 625 -- colonies in, British, 180 Adolf, Grand Duke of Luxemburg, 796 -- colonies in, French, 556 1222 THE STATESMAN'S YEAR-BOOK, 1900 AFR AMI Africa, Colonies in, German, 620 Algeria, army, 530, 558 -- Italian, 768 - books of reference, 560 -- Portuguese, 907 - commerce, 559 -- Spanish, 1041 - crime, 557 Agana (Ladrones), 1200 - defence, 558 Agra, 135 - exports, 559, 560 Agone (W. -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

A Study of Muslim Economic Thinking in the 11Th A.H

Munich Personal RePEc Archive A study of Muslim economic thinking in the 11th A.H. / 17th C.E. century Islahi, Abdul Azim Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75431/ MPRA Paper No. 75431, posted 06 Dec 2016 02:55 UTC Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Research Center King Abdulaziz University Scientific Publising Centre King Abdulaziz University P.O. Box 80200, Jeddah, 21589 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia FOREWORD There are numerous works on the history of Islamic economic thought. But almost all researches come to an end in 9th AH/15th CE century. We hardly find a reference to the economic ideas of Muslim scholars who lived in the 16th or 17th century, in works dealing with the history of Islamic economic thought. The period after the 9th/15th century remained largely unexplored. Dr. Islahi has ventured to investigate the periods after the 9th/15th century. He has already completed a study on Muslim economic thinking and institutions in the 10th/16th century (2009). In the mean time, he carried out the study on Muslim economic thinking during the 11th/17th century, which is now in your hand. As the author would like to note, it is only a sketch of the economic ideas in the period under study and a research initiative. It covers the sources available in Arabic, with a focus on the heartland of Islam. There is a need to explore Muslim economic ideas in works written in Persian, Turkish and other languages, as the importance of these languages increased in later periods. -

The Clarion of Syria

AL-BUSTANI, HANSSEN,AL-BUSTANI, SAFIEDDINE | THE CLARION OF SYRIA The Clarion of Syria A PATRIOT’S CALL AGAINST THE CIVIL WAR OF 1860 BUTRUS AL-BUSTANI INTRODUCED AND TRANSLATED BY JENS HANSSEN AND HICHAM SAFIEDDINE FOREWORD BY USSAMA MAKDISI The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Simpson Imprint in Humanities. The Clarion of Syria Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The Clarion of Syria A Patriot’s Call against the Civil War of 1860 Butrus al-Bustani Introduced and Translated by Jens Hanssen and Hicham Safieddine Foreword by Ussama Makdisi university of california press University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2019 by Jens Hanssen and Hicham Safieddine This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hanssen, Jens, author & translator.