Henry Purcell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

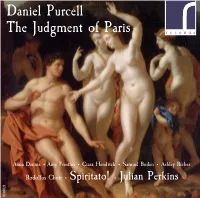

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites

133 The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites Alexander McGrattan Introduction In May 1660 Charles Stuart agreed to Parliament's terms for the restoration of the monarchy and returned to London from exile in France. After eighteen years of political turmoil, which culminated in the puritanical rule of the Commonwealth, Charles II's initial priorities on his accession included re-establishing a suitable social and cultural infrastructure for his court to function. At the outbreak of the civil war in 1642, Parliament had closed the London theatres, and performances of plays were banned throughout the interregnum. In August 1660 Charles issued patents for the establishment of two theatre companies in London. The newly formed companies were patronized by royalty and an aristocracy eager to circulate again in courtly circles. This led to a shift in the focus of theatrical activity from the royal court to the playhouses. The restoration of commercial theatres had a profound effect on the musical life of London. The playhouses provided regular employment to many of its most prominent musicians and attracted others from abroad. During the final quarter of the century, by which time the audiences had come to represent a wider cross-section of London society, they provided a stimulus to the city's burgeoning concert scene. During the Restoration period—in theatrical terms, the half-century following the Restoration of the monarchy—approximately six hundred productions were presented on the London stage. The vast majority of these were spoken dramas, but almost all included a substantial amount of music, both incidental (before the start of the drama and between the acts) and within the acts, and many incorporated masques, or masque-like episodes. -

'Inspire Us Genius of the Day': Rewriting the Regent in the Birthday Ode for Queen Anne, 1703

Eighteenth-Century Music 13/1, 1–21 © Cambridge University Press, 2015 doi:10.1017/S1478570615000421 ‘inspire us genius of the day’: 1 rewriting the regent in the birthday 2 ode for queen anne, 1703 3 estelle murphy 4 ! 5 ABSTRACT 6 In 1701–1702 writer and poet Peter Anthony Motteux collaborated with composer John Eccles, Master of the King’s 7 Musick, in writing the ode for King William III’s birthday. Eccles’s autograph manuscript is listed in the British 8 library manuscript catalogue as ‘Ode for the King’s Birthday, 1703; in score by John Eccles’ and is accompanied 9 by a claim that the ode had already reached folio 10v when William died, requiring the words to be amended to 10 suit his successor, Queen Anne. A closer inspection of this manuscript reveals that much more of the ode had been 11 completed before the king’s death, and that much more than the words ‘king’ and ‘William’ was amended to suit 12 a succeeding monarch of a different gender and nationality. The work was performed before Queen Anne on her 13 birthday in 1703 and the words were published shortly afterwards. Discrepancies between the printed text and 14 that in Eccles’s score indicate that no fewer than three versions of the text were devised during the creative process. 15 These versions raise issues of authority with respect to poet and composer. A careful analysis of the manuscript’s 16 paper types and rastrology reveals a collaborative process of re-engineering that was, in fact, applied to an already 17 completed work. -

Rev. William Davenant) Three Musical Settings of the Witches’ Scenes in Macbeth Survive

Folger Shakespeare Library Performing Restoration Shakespeare 1. Manuscripts Macbeth (rev. William Davenant) Three musical settings of the witches’ scenes in Macbeth survive. The first, by Matthew Locke, only survives in fragmentary form (see printed sources below). The second, by John Eccles, dates from ca. 1694. The third setting, by Richard Leveridge, dates from ca. 1702 and was performed well into the 19th century. The Folger holds several important sources for the Macbeth music, as noted below. (Charteris 108) W.a.222-227 and W.b.554-564 Partbooks copied ca. 1800 with later additions. Volumes were used in, and probably compiled for, the Oxford University Music Room concerts. Leveridge’s Macbeth music appears in W.a.222-227 and W.b.554-561. (Charteris 115) W.b.529 Copied in the late eighteenth century. The first section consists of miscellaneous pieces, whereas the second section is devoted to Richard Leveridge’s Macbeth, which includes theatrical cues. (Charteris 117) W.b.531 Manuscript score with John Eccles’s Macbeth music. Copied from Lbl. Add. Ms. 12219 by Thomas Oliphant in the mid-nineteenth century. (Charteris 122) W.b.536 Manuscript score with Richard Leveridge’s Macbeth music. Copied in late eighteenth century. (Charteris 123) W.b.537 Manuscript score with Leveridge’s Macbeth music. Copied in the early eighteenth century with later additions. First owner of the manuscript was almost certainly the Drury Lane Theatre. (Charteris 126) W.b.540 Manuscript score with Leveridge’s Macbeth music. Copied in the mid-eighteenth century. (Charteris 131) W.b.548 Manuscript score with Leveridge’s Macbeth music. -

John Travers: 18 Canzonets for Two and Three Voices (1746) Emanuel Rubin University of Massachusetts - Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Music & Dance Department Faculty Publication Music & Dance Series 2005 John Travers: 18 Canzonets for Two and Three Voices (1746) Emanuel Rubin University of Massachusetts - Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/music_faculty_pubs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Rubin, Emanuel, "John Travers: 18 Canzonets for Two and Three Voices (1746)" (2005). Music & Dance Department Faculty Publication Series. 3. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/music_faculty_pubs/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music & Dance at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music & Dance Department Faculty Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. John Travers’ Canzonets and their Georgian Context Emanuel Rubin, University of Massachusetts As the Baroque drew to a close, England’s native composers, outmaneuvered by foreigners who dominated the opera and concert stage, found a voice of their own by tapping into the rich tradition of Elizabethan and Restoration part song. John Travers’ delightful collection of canzonets for two and three voices with continuo is typical of this neglected body of music, and it should disabuse musicians once and for all of the canard that there was “no English music after Purcell.” At the historical moment when abstract instrumental music was taking continental Europe by storm, the English, with their long-standing admiration of poetry and song, devoted their energy to cultivation of cleverly wrought part songs for highly skilled amateur singers. In that “Silver Age” of British poetry, lyrics by Addison, Chatterton, Johnson, MacPherson, Pope, Prior, Ramsay, Shenstone, and Smollett were lovingly set as witty canzonets, sentimental glees, and rowdy catches in a flowering of vocal ensemble compositions unmatched anywhere else. -

Purcell King Arthur Semi-Staged Performance Tuesday 3 October 2017 7Pm, Hall

Purcell King Arthur semi-staged performance Tuesday 3 October 2017 7pm, Hall Academy of Ancient Music AAM Choir Richard Egarr director/harpsichord Daisy Evans stage director Jake Wiltshire lighting director Thomas Lamers dramaturg Ray Fearon narrator Louise Alder soprano Mhairi Lawson soprano Reginald Mobley countertenor Charles Daniels tenor Ivan Ludlow baritone Ashley Riches bass-baritone Marco Borggreve Marco Rosie Purdie assistant stage director Jocelyn Bundy stage manager Hannah Walmsley assistant stage manager There will be one interval of 20 minutes after Part 1 Part of Barbican Presents 2017–18 Part of Academy of Ancient Music 2017–18 Generously supported by the Geoffrey C Hughes Charitable Trust as part of the AAM Purcell Opera Cycle Confectionery and merchandise including organic ice cream, quality chocolate, nuts and nibbles are available from the sales points in our foyers. Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know The City of London during your visit. Additional feedback can be given Corporation is the founder and online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods principal funder of located around the foyers. the Barbican Centre Welcome Tonight marks the second instalment in a directly to a modern audience in the Brexit three-year series of semi-stagings of Purcell era. The subject of national identity – works, co-produced by the Barbican and central to King Arthur – has never seemed Academy of Ancient Music. Following a more pertinent. hugely successful Fairy Queen last season, AAM Music Director Richard Egarr and This piece contains some of Purcell’s stage director Daisy Evans once again most visit and beautiful music – including combine in this realisation of Purcell’s the celebrated aria ‘Fairest isle’ – and King Arthur. -

Dramatic Themes in John Eccles's 1707 Setting of William Congreve's Semele

Dramatic Themes in John Eccles's 1707 Setting of William Congreve's Semele Robert T. Kelley 2003 Introduction Anthony Rooley (2002) has asserted that \Eccles awaits the searching light of unbiased study and, particularly, informed performance." In this talk, I attempt to engage in such a study of Eccles's Semele. This opera is rich with interpretive possibilities and subtext, and I will present an analysis of the music that supports a view of the opera as a dramatically unified whole. This supports Rooley's musicological contention that \Here Congreve and the composer John Eccles worked very closely together, as they had for over a decade, and must have discussed at endless length their combined approach to creating this piece of music theatre." In an analysis that highlights the relationship between Congreve's text and Eccles's music, I will discuss musical connections that can help listeners uncover this opera's dramatic fusion of text and music. The first manner in which the music supports the drama is in the Baroque figures that accompany certain themes or dramatic situations in the opera. The second way that the music supports the text and stage action is through the work's key scheme. According to the Baroque doctrine of affections, different keys are associated with different passions. The qualities of the keys, which are highlighted by the 1 tuning of the Baroque keyboard instruments accompanying the ensemble, serve to highlight character development throughout the opera. This study reveals subtle dramatic subtext that is enhanced by the musical setting of the text and that suggests interpretive possibilities in the staging and musical performance. -

Composing After the Italian Manner: the English Cantata 1700-1710

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Faculty Publications Music 2014 Composing after the Italian Manner: The nE glish Cantata 1700-1710 Jennifer Cable University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/music-faculty-publications Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Cable, Jennifer. "Composing after the Italian Manner: The nE glish Cantata 1700-1710." In The Lively Arts of the London Stage: 1675-1725, edited by Kathryn Lowerre, 63-83. Farnham: Ashgate, 2014. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 4 Composing after the Italian Manner: The English Cantata 1700-1710 Jennifer Cable Charles Gildon, in addressing the state of the arts in his 1710 publication The Life of Mr. Thomas Betterton, the Late Eminent Tragedian, offered the following observation concerning contemporary music and, in particular, the music of Henry Purcell: Music, as well as Verse, is subject to that Rule of Horace; He that would have Spectators share his Grief, Must write not only well, but movingly. 1 According to Gildon, the best judges of music were the 'Masters ofComposition', and he called on them to be the arbiters of whether the taste in music had been improved since Purcell's day.2 However, Gildon's English 'masters of composition' were otherwise occupied, as they were just beginning to come to terms with what was surely a concerning, if not outright frustrating, situation. -

Early Music 2021

T71 Early Music 2021 Including the editions of AUGENER � GALLIARD � WEEKES � JOSEPH WILLIAMS EARLY MUSIC Contents Preface ................................................................................................................. 2 Ordering Information............................................................................................. 3 Keyboard Music .................................................................................................... 4 Composer Collections ..................................................................................... 4 Anthologies ..................................................................................................... 5 Piano Duet ...................................................................................................... 6 Music for Organ ............................................................................................... 6 Instrumental: Strings, Wind and Brass ................................................................. 7 Violin ............................................................................................................... 7 Viola ................................................................................................................ 7 Cello ................................................................................................................ 7 Double Bass .................................................................................................... 7 Lute ................................................................................................................ -

Folger Shakespeare Library Performing Restoration Shakespeare

Folger Shakespeare Library Performing Restoration Shakespeare 1. Manuscripts Macbeth (rev. William Davenant) Three musical settings of the witches’ scenes in Macbeth survive. The first, by Matthew Locke, only survives in fragmentary form (see printed sources below). The second, by John Eccles, dates from ca. 1694. The third setting, by Richard Leveridge, dates from ca. 1702 and was performed well into the 19th century and this is the one we will perform in the workshop. Workshop participants should have access to selected manuscript sources (they also will be useful for those who are not musically literate, as many bear the traces of performance). (Charteris 108) W.a.222-227 and W.b.554-564 Partbooks copied ca. 1800 with later additions. Volumes were used in, and probably compiled for, the Oxford University Music Room concerts. Leveridge’s Macbeth music appears in W.a.222-227 and W.b.554-561. (Charteris 115) W.b.529** Copied in the late eighteenth century. The first section consists of miscellaneous pieces, whereas the second section is devoted to Richard Leveridge’s Macbeth, which includes theatrical cues. (Charteris 117) W.b.531 Manuscript score with John Eccles’s Macbeth music. Copied from Lbl. Add. Ms. 12219 by Thomas Oliphant in the mid-nineteenth century. (Charteris 122) W.b.536 Manuscript score with Richard Leveridge’s Macbeth music. Copied in late eighteenth century. (Charteris 123) W.b.537** Manuscript score with Leveridge’s Macbeth music. Copied in the early eighteenth century with later additions. First owner of the manuscript was almost certainly the Drury Lane Theatre. -

When Eros Meets Thanatos: the Bedchamber Scenes in Congreve/Eccles’S and Handel/Hamilton’S Semele(S)

© 2019 ARRÊT SUR SCÈNE / SCENE FOCUS (IRCL-UMR5186 du CNRS) ISSN 2268-977X. Tous droits réservés. Reproduction soumise à autorisation. Téléchargement et impression autorisés à usage personnel. www.ircl.cnrs.fr When Eros meets Thanatos: the bedchamber scenes in Congreve/Eccles’s and Handel/Hamilton’s Semele(s) Pierre DEGOTT Université de Lorraine Among the works of Handel’s maturity, Semele stands out as an anomaly. Given at Covent Garden in February 1744, the piece was first performed in an unstaged version, “in the Manner of an Oratorio”, even though in terms of form and subject matter it is undeniably a fully fledged opera. The libretto, initially written by William Congreve in 1707 for the composer John Eccles, bears all the characteristics of a work meant to be played onstage.1 The relative failure of this unique composition – it is one of a small number of dramatic works never to have been performed again in Handel’s lifetime – can no doubt be explained by its incompatibility with contemporary audience expectations. Obviously, the performance of an openly erotic work during Lent did not go down well with the more middle-class, puritanical public of the 1740s, not to mention the literary origins of a story based on Ovid’s Metamorphoses (Book III, II.251–313). The sexual imagery of the libretto did actually put off the English oratorio-going public of the 1740s, more concerned with moral edification than with the type of sexual titillation that characterises a libretto initially written by a master of the Restoration: “No Oratorio, but a baudy opera”, was the irrevocable comment made by Charles Jennens, the librettist of Handel’s Messiah.2 Another reason for the relatively cold reception of the work may also have stemmed from the fact that Handel, withdrawn from the world of opera, had recently refused Lord Middlesex’s offer to compose an opera in Italian for the company he had founded in 1739. -

Stoddard Lincoln John Eccles: the Last of a Tradition

Stoddard Lincoln John Eccles: The last of a tradition 1963 unpublished diss., Oxford University. Franklin Zimmerman The value of the work appearing recently under this somewhat ro- mantically subtitled caption can best be summed up by saying that it fills a long-felt need for a study in depth of an important composer of the post-Purcellian schoo!. Moreover, it fills the need through expert handling of an enormous amount of detail, much of which is the result of original research and analysis. Its total worth is such that it is cer- tain to be an important item in the bibliographies of future scholars of English music of the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Placing Eccles in the as-yet-seldom-researched hiatus between the periods of Purcell and Handel in the history of English music, Mr. Lincoln first sorts out a few genealogical problems, then sets to work on his main task: to discover Eccles' significance in native musical de- velopments in London during the post-Purcellian twilight and to diag- nose the ills which brought these developments to nothing. Reflecting upon the aesthetic interworkings of earlier English musical and poetical traditions, he formulates and substantiates the notion that it has been the awkwardness of the English language when sung which has imposed upon musician and lyric poet their most difficult problems. For the music dramatist with classical ideals these problems have been virtually insurmountable. Comparing the achievements and methods of Henry Lawes to those of Lully, Mr. Lincoln then traces the development of the rhetorical style of the Lawes brothers, following it up to the late 1670's when Pietro Reggio appeared in England to introduce Italianate melismas, both structural and illustrative.