The Historical Context of Handel's Semele

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

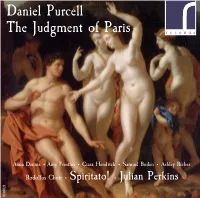

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011 the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard college About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk-taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium-arch space; and in the 220-seat Theater Two, which features a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, operetta, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrates its 22nd year in August, with “Sibelius and His World.” The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, the former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the contributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. We are grateful for their support and welcome all donations. ©2011 Bard College. All rights reserved. Cover Danae and the Shower of Gold (krater detail), ca. 430 bce. Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY. Inside Back Cover ©Peter Aaron ’68/Esto The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College Chair Jeanne Donovan Fisher President Leon Botstein Honorary Patron Martti Ahtisaari, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and former president of Finland Die Liebe der Danae (The Love of Danae) Music by Richard Strauss Libretto by Joseph Gregor, after a scenario by Hugo von Hofmannsthal Directed by Kevin Newbury American Symphony Orchestra Conducted by Leon Botstein, Music Director Set Design by Rafael Viñoly and Mimi Lien Choreography by Ken Roht Costume Design by Jessica Jahn Lighting Design by D. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

The Return of Handel's Giove in Argo

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL 1685-1759 Giove in Argo Jupiter in Argos Opera in Three Acts Libretto by Antonio Maria Lucchini First performed at the King’s Theatre, London, 1 May 1739 hwv a14 Reconstructed with additional recitatives by John H. Roberts Arete (Giove) Anicio Zorzi Giustiniani tenor Iside Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Erasto (Osiri) Vito Priante bass Diana Theodora Baka mezzo-soprano Calisto Karina Gauvin soprano Licaone Johannes Weisser baritone IL COMPLESSO BAROCCO Alan Curtis direction 2 Ouverture 1 Largo – Allegro (3:30) 1 2 A tempo di Bourrée (1:29) ATTO PRIMO 3 Coro Care selve, date al cor (2:01) 4 Recitativo: Licaone Imbelli Dei! (0:48) 5 Aria: Licaone Affanno tiranno (3:56) 6 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (3:20) 7 Recitativo: Diana Della gran caccia, o fide (0:45) 8 Aria: Diana Non ingannarmi, cara speranza (7:18) 9 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (1:12) 10 Aria: Iside Deh! m’aiutate, o Dei (2:34) 11 Recitativo: Iside Fra il silenzio di queste ombrose selve (1:01) 12 Arioso: Iside Vieni, vieni, o de’ viventi (1:08) 13 Recitativo: Arete Iside qui, fra dolce sonno immersa? (0:23) 14 Aria: Arete Deh! v’aprite, o luci belle (3:38) 15 Recitativo: Iside, Arete Olà? Chi mi soccorre? (1:39) 16 Aria: Iside Taci, e spera (3:39) 17 Arioso: Calisto Tutta raccolta ancor (2:03) 18 Recitativo: Calisto, Erasto Abbi, pietoso Cielo (1:52) 19 Aria: Calisto Lascia la spina (2:43) 20 Recitativo: Erasto, Arete Credo che quella bella (1:23) 21 Aria: Arete Semplicetto! a donna credi? (6:11) 22 Recitativo: Erasto Che intesi mai? (0:23) 23 Aria: Erasto -

Your Tuneful Voice Iestyn Davies

VIVAT-105-Booklet.pdf 1 18/11/13 20:22 YOUR TUNEFUL VOICE Handel Oratorio Arias IESTYN DAVIES CAROLYN SAMPSON THE KING’S CONSORT ROBERT KING VIVAT-105-Booklet.pdf 2 18/11/13 20:22 YOUR TUNEFUL VOICE Handel Oratorio Arias 1 O sacred oracles of truth (from Belshazzar) [5’01] Who calls my parting soul from death (from Es ther) [3’13] with Carolyn Sampson soprano 2 Mortals think that Time is sleeping (from The Triumph of Time and Truth) [7’05] On the valleys, dark and cheerless (from The Triumph of Time and Truth) [4’00] 3 Tune your harps to cheerful strains (from Es ther) [4’45] with Rachel Chaplin oboe How can I stay when love invites (from Es ther) [3’06] 4 Mighty love now calls to arm (from Alexander Balus) [2’35] 5 Overture to Jephtha [6’47] 5 [Grave] – Allegro – [Grave] [5’09] 6 Menuet [1’38] 7 Eternal source of light divine (from Birthday Ode for Queen Anne) [3’35] with Crispian Steele-Perkins trumpet 8 Welcome as the dawn of day (from Solomon) [3’32] with Carolyn Sampson soprano 9 Your tuneful voice my tale would tell (from Semele) [5’12] with Kati Debretzeni solo violin 10 Yet can I hear that dulcet lay (from The Choice of Hercules) [3’49] 11 Up the dreadful steep ascending (from Jephtha) [3’36] 12 Overture to Samson [7’43] 12 Andante – Adagio [3’17] 13 Allegro – Adagio [1’37] 14 Menuetto [2’49] 15 Thou shalt bring them in (from Israel in Egypt) [3’15] VIVAT-105-Booklet.pdf 3 18/11/13 20:22 O sacred oracles of truth (from Belshazzar) [5’01] 16 Who calls my parting soul from death (from Es ther) [3’13] with Carolyn Sampson soprano -

The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites

133 The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites Alexander McGrattan Introduction In May 1660 Charles Stuart agreed to Parliament's terms for the restoration of the monarchy and returned to London from exile in France. After eighteen years of political turmoil, which culminated in the puritanical rule of the Commonwealth, Charles II's initial priorities on his accession included re-establishing a suitable social and cultural infrastructure for his court to function. At the outbreak of the civil war in 1642, Parliament had closed the London theatres, and performances of plays were banned throughout the interregnum. In August 1660 Charles issued patents for the establishment of two theatre companies in London. The newly formed companies were patronized by royalty and an aristocracy eager to circulate again in courtly circles. This led to a shift in the focus of theatrical activity from the royal court to the playhouses. The restoration of commercial theatres had a profound effect on the musical life of London. The playhouses provided regular employment to many of its most prominent musicians and attracted others from abroad. During the final quarter of the century, by which time the audiences had come to represent a wider cross-section of London society, they provided a stimulus to the city's burgeoning concert scene. During the Restoration period—in theatrical terms, the half-century following the Restoration of the monarchy—approximately six hundred productions were presented on the London stage. The vast majority of these were spoken dramas, but almost all included a substantial amount of music, both incidental (before the start of the drama and between the acts) and within the acts, and many incorporated masques, or masque-like episodes. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

Handel Arias

ALICE COOTE THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET HANDEL ARIAS HERCULES·ARIODANTE·ALCINA RADAMISTO·GIULIO CESARE IN EGITTO GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL A portrait attributed to Balthasar Denner (1685–1749) 2 CONTENTS TRACK LISTING page 4 ENGLISH page 5 Sung texts and translation page 10 FRANÇAIS page 16 DEUTSCH Seite 20 3 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685–1759) Radamisto HWV12a (1720) 1 Quando mai, spietata sorte Act 2 Scene 1 .................. [3'08] Alcina HWV34 (1735) 2 Mi lusinga il dolce affetto Act 2 Scene 3 .................... [7'45] 3 Verdi prati Act 2 Scene 12 ................................. [4'50] 4 Stà nell’Ircana Act 3 Scene 3 .............................. [6'00] Hercules HWV60 (1745) 5 There in myrtle shades reclined Act 1 Scene 2 ............. [3'55] 6 Cease, ruler of the day, to rise Act 2 Scene 6 ............... [5'35] 7 Where shall I fly? Act 3 Scene 3 ............................ [6'45] Giulio Cesare in Egitto HWV17 (1724) 8 Cara speme, questo core Act 1 Scene 8 .................... [5'55] Ariodante HWV33 (1735) 9 Con l’ali di costanza Act 1 Scene 8 ......................... [5'42] bl Scherza infida! Act 2 Scene 3 ............................. [11'41] bm Dopo notte Act 3 Scene 9 .................................. [7'15] ALICE COOTE mezzo-soprano THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET conductor 4 Radamisto Handel diplomatically dedicated to King George) is an ‘Since the introduction of Italian operas here our men are adaptation, probably by the Royal Academy’s cellist/house grown insensibly more and more effeminate, and whereas poet Nicola Francesco Haym, of Domenico Lalli’s L’amor they used to go from a good comedy warmed by the fire of tirannico, o Zenobia, based in turn on the play L’amour love and a good tragedy fired with the spirit of glory, they sit tyrannique by Georges de Scudéry. -

Richard and Mildred Crooks Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3z09q52j No online items Guide to the Richard and Mildred Crooks Collection Andrea Castillo and Nancy Lorimer Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound Stanford University Libraries Braun Music Center 541 Lasuen Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3076 Phone: (650) 723-9312 Fax: (650) 725-1145 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www-sul.stanford.edu/depts/ars/ #169; 2006 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Richard and Mildred ARS-0004 1 Crooks Collection Guide to the Richard and Mildred Crooks Collection Collection number: ARS-0004 Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Processed by: Andrea Castillo and Nancy Lorimer Date Completed: May 2006 Encoded by: Ray Heigemeir #169; 2006 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Richard and Mildred Crooks Collection Dates: 1913-1984 Collection number: ARS-0004 Creator: Richard and Mildred Crooks Collection Size: 9 linear ft. Repository: Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California 94305-3076 Abstract: Materials documenting virtually every stage of Crooks career. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open for research. Listening appointments may require 24 hours notice. Contact the Archive Operations Manager. Publication Rights Property rights reside with repository. Publication and reproduction rights reside with the creators or their heirs. To obtain permission to publish or reproduce, please contact the Head Librarian of the Archive of Recorded Sound. Preferred Citation RIchard and Mildred Crooks Collection, ARS-0004. Courtesy of the Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. -

Opening Nights at the Opera 1641–1744

Cambridge University Press 0521851459 - The Transvestite Achilles: Gender and Genre in Statius’ Achilleid P. J. Heslin Excerpt More information 1 Opening N ights at the Opera 1641–1744 Eccoti ò Lettore in questi giorni di Carnevale un’Achille in maschera. Preface to L’Achille in Sciro, Ferrara 1663* ver the course of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth cen- turies, the story of Achilles in Scyros was represented many times on operatic stages across Europe. Given the nature of the young genre, it O 1 is not hard to see why this motif was popular. To illustrate the principle, con- trast the Elizabethan theater, where the custom of boy actors playing the parts of women lent a certain piquancy to plots in which a female character dressed as a man: thus a boy played a woman playing a man. In Baroque opera, the sit- uation was reversed. The primary roles were almost invariably scored for high voices, which could only be sung by a woman or a man whose secondary sexual 2 characteristics had not developed. In most cases the choice between a female singer and a castrato seems to have been determined by the local availability of 3 singers rather than the pursuit of naturalism. It was not impossible to see the * “In these days of Carnival, here is Achilles wearing a mask for you, dear reader.” On this text, see below (p 11). 1 Thus Rosselli (1992: 58). 2 This was accomplished by cutting the spermatic cords or by orchidectomy before puberty: see Jenkins (1998) on the procedure and physiology, and on the social context, see Rosselli (1988)or more succinctly Rosselli (1992: 32–55). -

HANDEL Acis and Galatea

SUPER AUDIO CD HANDEL ACIS AND GALATEA Lucy Crowe . Allan Clayton . Benjamin Hulett Neal Davies . Jeremy Budd Early Opera Company CHANDOS early music CHRISTIAN CURNYN GEOR G E FRIDERICH A NDEL, c . 1726 Portrait attributed to Balthasar Denner (1685 – 1749) © De Agostini / Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library GeoRge FRIdeRIC Handel (1685–1759) Acis and Galatea, HWV 49a (1718) Pastoral entertainment in one act Libretto probably co-authored by John Gay, Alexander Pope, and John Hughes Galatea .......................................................................................Lucy Crowe soprano Acis ..............................................................................................Allan Clayton tenor Damon .................................................................................Benjamin Hulett tenor Polyphemus...................................................................Neal Davies bass-baritone Coridon ........................................................................................Jeremy Budd tenor Soprano in choruses ....................................................... Rowan Pierce soprano Early Opera Company Christian Curnyn 3 COMPACT DISC ONE 1 1 Sinfonia. Presto 3:02 2 2 Chorus: ‘Oh, the pleasure of the plains!’ 5:07 3 3 Recitative, accompanied. Galatea: ‘Ye verdant plains and woody mountains’ 0:41 4 4 Air. Galatea: ‘Hush, ye pretty warbling choir!’. Andante 5:57 5 5 [Air.] Acis: ‘Where shall I seek the charming fair?’. Larghetto 2:50 6 6 Recitative. Damon: ‘Stay, shepherd, stay!’ 0:21 7 7 Air. Damon: ‘Shepherd, what art thou pursuing?’. Andante 4:05 8 8 Recitative. Acis: ‘Lo, here my love, turn, Galatea, hither turn thy eyes!’ 0:21 9 9 Air. Acis: ‘Love in her eyes sits playing’. Larghetto 6:15 10 10 Recitative. Galatea: ‘Oh, didst thou know the pains of absent love’ 0:13 11 11 Air. Galatea: ‘As when the dove’. Andante 5:53 12 12 Duet. Acis and Galatea: ‘Happy we!’. Presto 2:48 TT 37:38 4 COMPACT DISC TWO 1 14 Chorus: ‘Wretched lovers! Fate has past’.