Your Tuneful Voice Iestyn Davies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

Sally Matthews Is Magnificent

` DVORAK Rusalka, Glyndebourne Festival, Robin Ticciati. DVD Opus Arte Sally Matthews is magnificent. During the Act II court ball her moral and social confusion is palpable. And her sorrowful return to the lake in the last act to be reviled by her water sprite sisters would melt the winter ice. Christopher Cook, BBC Music Magazine, November 2020 Sally Matthews’ Rusalka is sung with a smoky soprano that has surprising heft given its delicacy, and the Prince is Evan LeRoy Johnson, who combines an ardent tenor with good looks. They have great chemistry between them and the whole cast is excellent. Opera Now, November-December 2020 SCHUMANN Paradies und die Peri, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Paolo Bortolameolli Matthews is noted for her interpretation of the demanding role of the Peri and also appears on one of its few recordings, with Rattle conducting. The soprano was richly communicative in the taxing vocal lines, which called for frequent leaps and a culminating high C … Her most rewarding moments occurred in Part III, particularly in “Verstossen, verschlossen” (“Expelled again”), as she fervently Sally Matthews vowed to go to the depths of the earth, an operatic tour-de-force. Janelle Gelfand, Cincinnati Business Courier, December 2019 Soprano BARBER Two Scenes from Anthony & Cleopatra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Juanjo Mena This critic had heard a fine performance of this music by Matthews and Mena at the BBC Proms in London in 2018, but their performance here on Thursday was even finer. Looking suitably regal in a glittery gold form-fitting gown, the British soprano put her full, vibrant, richly contoured voice fully at the service of text and music. -

Press Information Eno 2013/14 Season

PRESS INFORMATION ENO 2013/14 SEASON 1 #ENGLISHENO1314 NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 CONTENTS Autumn 2013 4 FIDELIO Beethoven 6 DIE FLEDERMAUS Strauss 8 MADAM BUtteRFLY Puccini 10 THE MAGIC FLUte Mozart 12 SATYAGRAHA Glass Spring 2014 14 PeteR GRIMES Britten 18 RIGOLetto Verdi 20 RoDELINDA Handel 22 POWDER HeR FAce Adès Summer 2014 24 THEBANS Anderson 26 COSI FAN TUtte Mozart 28 BenvenUTO CELLINI Berlioz 30 THE PEARL FISHERS Bizet 32 RIveR OF FUNDAMent Barney & Bepler ENGLISH NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 3 FIDELIO NEW PRODUCTION BEETHoven (1770–1827) Opens: 25 September 2013 (7 performances) One of the most sought-after opera and theatre directors of his generation, Calixto Bieito returns to ENO to direct a new production of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio. Bieito’s continued association with the company shows ENO’s commitment to highly theatrical and new interpretations of core repertoire. Following the success of his Carmen at ENO in 2012, described by The Guardian as ‘a cogent, gripping piece of work’, Bieito’s production of Fidelio comes to the London Coliseum after its 2010 premiere in Munich. Working with designer Rebecca Ringst, Bieito presents a vast Escher-like labyrinth set, symbolising the powerfully claustrophobic nature of the opera. Edward Gardner, ENO’s highly acclaimed Music Director, 2013 Olivier Award-nominee and recipient of an OBE for services to music, conducts an outstanding cast led by Stuart Skelton singing Florestan and Emma Bell as Leonore. Since his definitive performance of Peter Grimes at ENO, Skelton is now recognised as one of the finest heldentenors of his generation, appearing at the world’s major opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera, New York, and Opéra National de Paris. -

2018–2019 Annual Report

18|19 Annual Report Contents 2 62 From the Chairman of the Board Ensemble Connect 4 66 From the Executive and Artistic Director Digital Initiatives 6 68 Board of Trustees Donors 8 96 2018–2019 Concert Season Treasurer’s Review 36 97 Carnegie Hall Citywide Consolidated Balance Sheet 38 98 Map of Carnegie Hall Programs Administrative Staff Photos: Harding by Fadi Kheir, (front cover) 40 101 Weill Music Institute Music Ambassadors Live from Here 56 Front cover photo: Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer, by Stephanie Berger. Stephanie by Chris “Critter” Eldridge, and Chris Thile National Youth Ensembles in Live from Here March 9 Daniel Harding and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra February 14 From the Chairman of the Board Dear Friends, In the 12 months since the last publication of this annual report, we have mourned the passing, but equally importantly, celebrated the lives of six beloved trustees who served Carnegie Hall over the years with the utmost grace, dedication, and It is my great pleasure to share with you Carnegie Hall’s 2018–2019 Annual Report. distinction. Last spring, we lost Charles M. Rosenthal, Senior Managing Director at First Manhattan and a longtime advocate of These pages detail the historic work that has been made possible by your support, Carnegie Hall. Charles was elected to the board in 2012, sharing his considerable financial expertise and bringing a deep love and further emphasize the extraordinary progress made by this institution to of music and an unstinting commitment to helping the aspiring young musicians of Ensemble Connect realize their potential. extend the reach of our artistic, education, and social impact programs far beyond In August 2019, Kenneth J. -

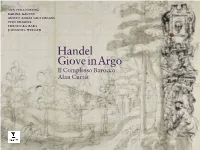

The Return of Handel's Giove in Argo

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL 1685-1759 Giove in Argo Jupiter in Argos Opera in Three Acts Libretto by Antonio Maria Lucchini First performed at the King’s Theatre, London, 1 May 1739 hwv a14 Reconstructed with additional recitatives by John H. Roberts Arete (Giove) Anicio Zorzi Giustiniani tenor Iside Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Erasto (Osiri) Vito Priante bass Diana Theodora Baka mezzo-soprano Calisto Karina Gauvin soprano Licaone Johannes Weisser baritone IL COMPLESSO BAROCCO Alan Curtis direction 2 Ouverture 1 Largo – Allegro (3:30) 1 2 A tempo di Bourrée (1:29) ATTO PRIMO 3 Coro Care selve, date al cor (2:01) 4 Recitativo: Licaone Imbelli Dei! (0:48) 5 Aria: Licaone Affanno tiranno (3:56) 6 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (3:20) 7 Recitativo: Diana Della gran caccia, o fide (0:45) 8 Aria: Diana Non ingannarmi, cara speranza (7:18) 9 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (1:12) 10 Aria: Iside Deh! m’aiutate, o Dei (2:34) 11 Recitativo: Iside Fra il silenzio di queste ombrose selve (1:01) 12 Arioso: Iside Vieni, vieni, o de’ viventi (1:08) 13 Recitativo: Arete Iside qui, fra dolce sonno immersa? (0:23) 14 Aria: Arete Deh! v’aprite, o luci belle (3:38) 15 Recitativo: Iside, Arete Olà? Chi mi soccorre? (1:39) 16 Aria: Iside Taci, e spera (3:39) 17 Arioso: Calisto Tutta raccolta ancor (2:03) 18 Recitativo: Calisto, Erasto Abbi, pietoso Cielo (1:52) 19 Aria: Calisto Lascia la spina (2:43) 20 Recitativo: Erasto, Arete Credo che quella bella (1:23) 21 Aria: Arete Semplicetto! a donna credi? (6:11) 22 Recitativo: Erasto Che intesi mai? (0:23) 23 Aria: Erasto -

The English Concert – Biography

The English Concert – Biography The English Concert is one of Europe’s leading chamber orchestras specialising in historically informed performance. Created by Trevor Pinnock in 1973, the orchestra appointed Harry Bicket as its Artistic Director in 2007. Bicket is renowned for his work with singers and vocal collaborators, including in recent seasons Lucy Crowe, Elizabeth Watts, Sarah Connolly, Joyce DiDonato, Alice Coote and Iestyn Davies. The English Concert has a wide touring brief and the 2014-15 season will see them appear both across the UK and abroad. Recent highlights include European and US tours with Alice Coote, Joyce DiDonato, David Daniels and Andreas Scholl as well as the orchestra’s first tour to mainland China. Harry Bicket directed The English Concert and Choir in Bach’s Mass in B Minor at the 2012 Leipzig Bachfest and later that year at the BBC proms, a performance that was televised for BBC4. Following the success of Handel’s Radamisto in New York 2013, Carnegie Hall has commissioned one Handel opera each season from The English Concert. Theodora followed in early 2014, which toured West Coast of the USA as well as the Théâtre des Champs Elysées Paris and the Barbican London followed by a critically acclaimed tour of Alcina in October 2014. Future seasons will see performances of Handel’s Hercules and Orlando. The English Concert’s discography includes more than 100 recordings with Trevor Pinnock for Deutsche Grammophon Archiv, and a series of critically acclaimed CDs for Harmonia Mundi with violinist Andrew Manze. Recordings with Harry Bicket have been widely praised, including Lucy Crowe’s debut solo recital, Il caro Sassone. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XXXII, Number 1 Spring 2017 AMERICAN HANDEL FESTIVAL 2017 : CONFERENCE REPORT Carlo Lanfossi This year, Princeton University (Princeton, NJ) hosted the biennial American Handel Festival on April 6-9, 2017. From a rainstorm on Thursday to a shiny Sunday, the conference unfolded with the usual series of paper sessions, two concerts, and a keynote address. The assortment of events reflected the kaleidoscopic variety of Handel’s scholarship, embodied by a group of academics and performers that spans several generations and that looks promising for the future of Handel with the exploration by Fredric Fehleisen (The Juilliard School) studies. of the network of musical associations in Messiah, highlighting After the opening reception at the Woolworth Music musical-rhetorical patterns through Schenkerian reductions Center, the first day of the conference was marked by the Howard and a request for the audience to hum the accompanying Serwer Memorial Lecture given by John Butt (University of harmony of “I know that my Redeemer liveth.” Finally, Minji Glasgow) on the title “Handel and Messiah: Harmonizing the Kim (Andover, MA) reconstructed an instance of self-borrowing Bible for a Modern World?” Reminding the audience of the in the chorus “I will sing unto the Lord” from Israel in Egypt, need to interrogate the cultural values inherent to the creation tracing the musical lineage to the incipit of the English canon of Messiah, Butt structured his keynote address around various “Non nobis, Domine” through its use in the Cannons anthem topics and methodologies, including an analysis of Handel’s Let God Arise and the Utrecht Te Deum . -

![The YOUNG Families of Early Giles Co TN 1101 Baxter Young and Lila Vou Holt, Was Born 14 July Reese Porter Young [Y19k4], Son of William 1908 in Giles Co TN](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2039/the-young-families-of-early-giles-co-tn-1101-baxter-young-and-lila-vou-holt-was-born-14-july-reese-porter-young-y19k4-son-of-william-1908-in-giles-co-tn-682039.webp)

The YOUNG Families of Early Giles Co TN 1101 Baxter Young and Lila Vou Holt, Was Born 14 July Reese Porter Young [Y19k4], Son of William 1908 in Giles Co TN

The YOUNG Families of Early Giles Co TN 1101 Baxter Young and Lila Vou Holt, was born 14 July Reese Porter Young [Y19k4], son of William 1908 in Giles Co TN. She married Clyde Duke about Carroll Young and Sarah Jane Rhea, was born 11 1928, probably at Nashville, and in 1930 they lived August 1849 at Culleoka, Maury Co TN, and moved at Nashville next door to her parents. Clyde was a with his family to Washington, Webster Co MO sign painter. He was born 30 December 1907 in TN, when he was a boy. He married Nancy Ona Haymes son of James E Duke and Ida Ann Nichols, and died in Webster Co on 18 June 1871. Reese was a at Nashville in October 1973. Rebecca died at Fort blacksmith and a farmer. He died in Webster Co on Smith AR on 18 April 1992. They had two children- 2 January 1937 from pneumonia. Morgan Young a. Betty Lou Duke, b Jan 1929 was the informant for his death certificate. Nancy b. Jerry Duke was born 30 October 1852 at Green City, Hickory James E Duke and Ida Ann Nichols were married 27 Co MO, daughter of William Brumfield Haymes May 1892 i n P u t n a m Co TN. (58,Z, 169m, (1821-1883) and Sarah Jane Dugan (1834-1908), 15v,18wf) and died in Webster Co on 27 January 1937 from pneumonia. Sam Young was the informant for her Rebecca J Young [Y3a2g12], daughter of John death certificate. They were buried in Saint Luke A Young and Ida Mae Hayter, was born in 1927 in Methodist Church Cemetery at Marshfield, Webster TX. -

The Baritone Voice in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: a Brief Examination of Its Development and Its Use in Handel’S Messiah

THE BARITONE VOICE IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES: A BRIEF EXAMINATION OF ITS DEVELOPMENT AND ITS USE IN HANDEL’S MESSIAH BY JOSHUA MARKLEY Submitted to the graduate degree program in The School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Stephens ________________________________ Dr. Michelle Hayes ________________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ________________________________ Dr. Julia Broxholm ________________________________ Mr. Mark Ferrell Date Defended: 06/08/2016 The Dissertation Committee for JOSHUA MARKLEY certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE BARITONE VOICE IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES: A BRIEF EXAMINATION OF ITS DEVELOPMENT AND ITS USE IN HANDEL’S MESSIAH ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Stephens Date approved: 06/08/2016 ii Abstract Musicians who want to perform Handel’s oratorios in the twenty-first century are faced with several choices. One such choice is whether or not to use the baritone voice, and in what way is best to use him. In order to best answer that question, this study first examines the history of the baritone voice type, the historical context of Handel’s life and compositional style, and performing practices from the baroque era. It then applies that information to a case study of a representative sample of Handel’s solo oratorio literature. Using selections from Messiah this study charts the advantages and disadvantages of having a baritone sing the solo parts of Messiah rather than the voice part listed, i.e. tenor or bass, in both a modern performance and an historically-informed performance in an attempt to determine whether a baritone should sing the tenor roles or bass roles and in what context. -

NEWSLETTER Editor: Francis Knights

NEWSLETTER Editor: Francis Knights Volume v/1 (Spring 2021) Welcome to the NEMA Newsletter, the online pdf publication for members of the National Early Music Association UK, which appears twice yearly. It is designed to share and circulate information and resources with and between Britain’s regional early music Fora, amateur musicians, professional performers, scholars, instrument makers, early music societies, publishers and retailers. As well as the listings section (including news, obituaries and organizations) there are a number of articles, including work from leading writers, scholars and performers, and reports of events such as festivals and conferences. INDEX Interview with Bruno Turner, Ivan Moody p.3 A painted villanella: In Memoriam H. Colin Slim, Glen Wilson p.9 To tie or not to tie? Editing early keyboard music, Francis Knights p.15 Byrd Bibliography 2019-2020, Richard Turbet p.20 The Historic Record of Vocal Sound (1650-1829), Richard Bethell p.30 Collecting historic guitars, David Jacques p.83 Composer Anniversaries in 2021, John Collins p.87 v2 News & Events News p.94 Obituaries p.94 Societies & Organizations p.95 Musical instrument auctions p.96 Conferences p.97 Obituary: Yvette Adams, Mark Windisch p.98 The NEMA Newsletter is produced twice yearly, in the Spring and Autumn. Contributions are welcomed by the Editor, email [email protected]. Copyright of all contributions remains with the authors, and all opinions expressed are those of the authors, not the publisher. NEMA is a Registered Charity, website http://www.earlymusic.info/nema.php 2 Interview with Bruno Turner Ivan Moody Ivan Moody: How did music begin for you? Bruno Turner: My family was musical. -

Advanced Technologies Are Both a Friend and a Threat to the U.S

Thursday, March 17, 2016 VOLUME LIII, NUMBER 11 Your Local News Source Since 1963 SERVING DUBLIN, LIVERMORE, PLEASANTON, SUNOL Advanced Technologies Are Both A Friend and a Threat to the U.S. By Jeff Garberson The technologies are high per- ist, according to Bruce Goodwin, can accelerate fabrication tenfold The combination of two ad- formance computing and additive an associate director at Lawrence again by compressing the slow, See Inside Section A vanced technologies is proving manufacturing (AM), often called Livermore National Laboratory. methodical sequences of trial and Section A is filled with both a friend and a foe to the U.S. three-dimensional printing. It accelerates the fabrication error into the lightning-fast pro- information about arts, people, It is offering vastly faster and less Additive manufacturing may process roughly tenfold, he said. cesses on the computer. entertainment and special events. wasteful manufacturing, but also allow a technician with the right Manufacturing operations can For the military, this unprec- There are education stories, a is threatening to spread access to equipment and a complete com- run all day and all night. A single edented speed opens the door to de- variety of features, and the arts destructive technologies that can puter file to build a toy for a child, technician can program many op- veloping weapons that have been and entertainment and easily be concealed by terrorists a hip joint for a surgeon -- or a erations at once. adapted to an evolving conflict bulletin board. and other hostile groups. high explosive bomb for a terror- High performance computing (See TECHNOLOGIES, page 2) Doolan Canyon Pleasanton Named a Salamander Initiative Recovery Area Aimed at Big Doolan Canyon been selected by the U.S. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XXVII, Number 2 Summer 2012 FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK SUMMER 2012 I would like to thank all the members of the Society who have paid their membership dues for 2012, and especially those who paid to be members of the Georg-Friedrich-Händel Gesellschaft and/or friends of The Handel Institute before the beginning of June, as requested by the Secretary/Treasurer. For those of you who have not yet renewed your memberships, may I urge you to do so. Each year the end of spring brings with it the Handel Festivals in Halle and Göttingen, the latter now regularly scheduled around the moveable date of Pentecost, which is a three-day holiday in Germany. Elsewhere in this issue of the Newsletter you will find my necessarily selective Report from Halle. While there I heard excellent reports on the staging of Amadigi at Göttingen. Perhaps other members of the AHS would be willing to provide reports on the performances at Göttingen, and also those at Halle that I was unable to attend. If so, I am sure that the Newsletter Angelica Kauffmann, British, born in Switzerland, 1741-1807 Portrait of Sarah Editor would be happy to receive them. Harrop (Mrs. Bates) as a Muse ca. 1780-81 Oil on canvas 142 x 121 cm. (55 7/8 x 47 5/8 in.) Princeton University Art Museum. Museum purchase, Surdna Fund The opening of the festival in Halle coincided and Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund 2010-11 photo: Bruce M. White with the news of the death of the soprano Judith Nelson, who was a personal friend to many of us.