The Baritone Voice in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: a Brief Examination of Its Development and Its Use in Handel’S Messiah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Voice Types in Opera

Voice Types in Opera In many of Central City Opera’s educational programs, we spend some time explaining the different voice types – and therefore character types – in opera. Usually in opera, a voice type (soprano, mezzo soprano, tenor, baritone, or bass) has as much to do with the SOUND as with the CHARACTER that the singer portrays. Composers will assign different voice types to characters so that there is a wide variety of vocal colors onstage to give the audience more information about the characters in the story. SOPRANO: “Sopranos get to be the heroine or the princess or the opera star.” – Eureka Street* “Sopranos always get to play the smart, sophisticated, sweet and supreme characters!” – The Great Opera Mix-up* A soprano is a woman’s voice type. There are many different kinds of sopranos within the general category: coloratura, lyric, and spinto are a few. Coloratura soprano: Diana Damrau as The Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute (Mozart): https://youtu.be/dpVV9jShEzU Lyric soprano: Mirella Freni as Mimi in La bohème (Puccini): https://youtu.be/yTagFD_pkNo Spinto soprano: Leontyne Price as Aida in Aida (Verdi): https://youtu.be/IaV6sqFUTQ4?t=1m10s MEZZO SOPRANO: “There are also mezzos with a lower, more exciting woman’s voice…We get to be magical or mythical characters and sometimes… we get to be boys.” – Eureka Street “Mezzos play magnificent, magical, mysterious, and miffed characters.” – The Great Opera Mix-up A mezzo soprano is a woman’s voice type. Just like with sopranos, there are different kinds of mezzo sopranos: coloratura, lyric, and dramatic. -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

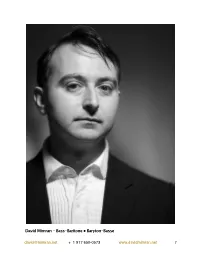

Bass-Baritone • Baryton-Basse [email protected] + 1 917 650-0573 1 100 Words Bio

David Mimran - Bass-Baritone • Baryton-Basse [email protected] + 1 917 650-0573 www.davidmimran.net 1 100 words bio Bass-Baritone David Mimran set aside a career as a lawyer in Paris to sing opera in New York. Great vocal flexibility in a wide tessitura, natural acting skills and a knowledge of nine languages including Italian, French, German, English, Spanish and Finnish allow for a large variety of repertoire. Roles on stage include Alcindoro/Benoît in Bohème, Conte Ceprano in Rigoletto, Niejus & Cascada in Merry Widow, Sarastro in Die Zauberflöte, Figaro & Antonio in Le nozze di Figaro, Morales & Zuniga in Carmen, Fiorello in Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Frank in Fledermaus, Lorenzo in I Capuletti e i Montecchi, Achille in Giulio Cesare and Melisso in Alcina. Languages French: Mother tongue English: Bilingual German, Italian, Spanish: Proficient Finnish, Portuguese, Hebrew: Working knowledge Russian, Hungarian: Basic phonetic reading knowledge I would consider studying a new language to sing a role. Stage Experience Full roles performed • Benoît/Alcindoro in Bohème - Opera Company of Brooklyn • Sciarrone/Jailer in Tosca - Regina Opera • Yakuside in Madama Butterfly - Bleecker Street Opera • Niejus and Cascada in The Merry Widow - Amore Opera • Sarastro in Die Zauberflöte - NY Lyric Opera Theater • Fiorello in Il Barbiere di Siviglia - Bleecker Street Opera • Lorenzo in I Capuletti e i Montecchi - Manhattan Chamber Opera • Spinelloccio/Nicolao in Gianni Schicchi - Regina Opera • Achilla in Giulio Cesare - Manhattan Chamber Opera • Docteur -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Historical Vocal Pedagogies

VC565 Historical Vocal Pedagogies Ian Howell [email protected] New England Conservatory of Music 23 September 2013 Monday, September 23, 13 Giulio Caccini b.1551 – d.1618 Florence, Italy Florentine Camerata – Recitative/Text Famous singer, music teacher, composer of Medici court Monday, September 23, 13 Giulio Caccini •Singers vs. instrumentalists •Voce piena, e naturale vs. voce finta •Avoid slides •Decrescendo from attack •Trillo vs. gruppo •Ornamentation for affect of text Monday, September 23, 13 Pier Francesco Tosi b.1647 – d.1742 Soprano Castrato Taught and performed across Europe, especially Vienna, London, and Bologna Monday, September 23, 13 Pier Francesco Tosi •Study solfeggio •voce di testa vs. voce di petto •Head voice soft ≠ shrieking trumpet •scales without separation of [h] or [g] •fast passages on [a], never [i] or [u] •avoid closed versions of [e] and [o] Monday, September 23, 13 Pier Francesco Tosi •Progressive exercises •expression towards a smile •Hold out the length of notes without shrillness and trembling •Messa di voce taught later •Teach on [a], [Ɛ], and [ɔ], not just on [a] •Drag voice high to low, but not low to high Monday, September 23, 13 Pier Francesco Tosi •Appoggiatura is most important grace •Trill is a necessity •No rules for teaching trill Monday, September 23, 13 Pier Francesco Tosi •Study with the mind •Listen to the best •Too much practice and vocal beauty incompatible Monday, September 23, 13 Giambattista Mancini b.1714 – d.1800 Bologna Castrato, studied with Bernacchi (also Senesino’s (Giulio Cesare) -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series Frank Morelli, Bassoon Behind every Juilliard artist is all of Juilliard —including you. With hundreds of dance, drama, and music performances, Juilliard is a wonderful place. When you join one of our membership programs, you become a part of this singular and celebrated community. by Claudio Papapietro Photo of cellist Khari Joyner Photo by Claudio Papapietro Become a member for as little as $250 Join with a gift starting at $1,250 and and receive exclusive benefits, including enjoy VIP privileges, including • Advance access to tickets through • All Association benefits Member Presales • Concierge ticket service by telephone • 50% discount on ticket purchases and email • Invitations to special • Invitations to behind-the-scenes events members-only gatherings • Access to master classes, performance previews, and rehearsal observations (212) 799-5000, ext. 303 [email protected] juilliard.edu The Juilliard School presents Faculty Recital: Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jesse Brault, Conductor Jonathan Feldman, Piano Jacob Wellman, Bassoon Wednesday, January 17, 2018, 7:30pm Paul Hall Part of the Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series GIOACHINO From The Barber of Seville (1816) ROSSINI (arr. François-René Gebauer/Frank Morelli) (1792–1868) All’idea di quell metallo Numero quindici a mano manca Largo al factotum Frank Morelli and Jacob Wellman, Bassoons JOHANNES Sonata for Cello, No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 38 (1862–65) BRAHMS Allegro non troppo (1833–97) Allegro quasi menuetto-Trio Allegro Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jonathan Feldman, Piano Intermission Program continues Major funding for establishing Paul Recital Hall and for continuing access to its series of public programs has been granted by The Bay Foundation and the Josephine Bay Paul and C. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

Minnesota Opera’S Production of La Traviata

The famous Brindisi in Minnesota Opera’s production of La Traviata. Photo by Dan Norman What can museums learn about attracting new audiences from Minnesota Opera? Summary Someone Who Speaks Their Language: How a Nontraditional Partner Brought New Audiences to Minneso- ta Opera is part of a series of case studies commissioned by The Wallace Foundation to explore arts and cultural organizations’ evidence-based efforts to reach new audiences and deepen relationships with their existing audiences. Each aspires to capture broadly applicable lessons about what works and what does not—and why—in building audiences. The American Alliance of Museums developed this overview to high- light the relevance of the case study for museums and promote cross-sector learning. The study tells the story of how one arts organization brought thousands of new visitors to its programs by partnering with an unconventional spokesperson. Minnesota Opera’s approach to reaching new audiences with messages that spoke to their interests is applicable to any museum looking to build new audiences. Challenge Like many organizations dedicated to traditional art forms, Minnesota Opera’s audience was “graying,” with patrons over sixty making up about half of its audience. While this older audience was loyal, and existing programs for young audiences showed promise, there was a gap for middle-aged people in between the ends of this spectrum. Audience Goal The Opera decided to reach out to women between the ages of thirty-five and sixty, because this demo- graphic showed unactualized potential in attendance data. They wanted to bust stereotypes that opera is a stagnant and irrelevant art form. -

The Return of Handel's Giove in Argo

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL 1685-1759 Giove in Argo Jupiter in Argos Opera in Three Acts Libretto by Antonio Maria Lucchini First performed at the King’s Theatre, London, 1 May 1739 hwv a14 Reconstructed with additional recitatives by John H. Roberts Arete (Giove) Anicio Zorzi Giustiniani tenor Iside Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Erasto (Osiri) Vito Priante bass Diana Theodora Baka mezzo-soprano Calisto Karina Gauvin soprano Licaone Johannes Weisser baritone IL COMPLESSO BAROCCO Alan Curtis direction 2 Ouverture 1 Largo – Allegro (3:30) 1 2 A tempo di Bourrée (1:29) ATTO PRIMO 3 Coro Care selve, date al cor (2:01) 4 Recitativo: Licaone Imbelli Dei! (0:48) 5 Aria: Licaone Affanno tiranno (3:56) 6 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (3:20) 7 Recitativo: Diana Della gran caccia, o fide (0:45) 8 Aria: Diana Non ingannarmi, cara speranza (7:18) 9 Coro Oh quanto bella gloria (1:12) 10 Aria: Iside Deh! m’aiutate, o Dei (2:34) 11 Recitativo: Iside Fra il silenzio di queste ombrose selve (1:01) 12 Arioso: Iside Vieni, vieni, o de’ viventi (1:08) 13 Recitativo: Arete Iside qui, fra dolce sonno immersa? (0:23) 14 Aria: Arete Deh! v’aprite, o luci belle (3:38) 15 Recitativo: Iside, Arete Olà? Chi mi soccorre? (1:39) 16 Aria: Iside Taci, e spera (3:39) 17 Arioso: Calisto Tutta raccolta ancor (2:03) 18 Recitativo: Calisto, Erasto Abbi, pietoso Cielo (1:52) 19 Aria: Calisto Lascia la spina (2:43) 20 Recitativo: Erasto, Arete Credo che quella bella (1:23) 21 Aria: Arete Semplicetto! a donna credi? (6:11) 22 Recitativo: Erasto Che intesi mai? (0:23) 23 Aria: Erasto -

The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1980 The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance. Malcolm Eugene Beauchamp Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Beauchamp, Malcolm Eugene, "The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance." (1980). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3474. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3474 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy.