1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång Till

Recommended Solos and Ensembles Tenor Trombone Solos Sång till Lotta, Jan Sandström. Edition Tarrodi: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991. Trombone and piano. Requires modest range (F – g flat1), well-developed lyricism, and musicianship. There are two versions of this piece, this and another that is scored a minor third higher. Written dynamics are minimal. Although phrases and slurs are not indicated, it is a SONG…encourage legato tonguing! Stephan Schulz, bass trombonist of the Berlin Philharmonic, gives a great performance of this work on YouTube - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mn8569oTBg8. A Winter’s Night, Kevin McKee, 2011. Available from the composer, www.kevinmckeemusic.com. Trombone and piano. Explores the relative minor of three keys, easy rhythms, keys, range (A – g1, ossia to b flat1). There is a fine recording of this work on his web site. Trombone Sonata, Gordon Jacob. Emerson Edition: Yorkshire, England, 1979. Trombone and piano. There are no real difficult rhythms or technical considerations in this work, which lasts about 7 minutes. There is tenor clef used throughout the second movement, and it switches between bass and tenor in the last movement. Range is F – b flat1. Recorded by Dr. Ron Babcock on his CD Trombone Treasures, and available at Hickey’s Music, www.hickeys.com. Divertimento, Edward Gregson. Chappell Music: London, 1968. Trombone and piano. Three movements, range is modest (G-g#1, ossia a1), bass clef throughout. Some mixed meter. Requires a mute, glissandi, and ad. lib. flutter tonguing. Recorded by Brett Baker on his CD The World of Trombone, volume 1, and can be purchased at http://www.brettbaker.co.uk/downloads/product=download-world-of-the- trombone-volume-1-brett-baker. -

Gustavo Dudamel 2020/21 Season (Long Biography)

GUSTAVO DUDAMEL 2020/21 SEASON (LONG BIOGRAPHY) Gustavo Dudamel is driven by the belief that music has the power to transform lives, to inspire, and to change the world. Through his dynamic presence on the podium and his tireless advocacy for arts education, Dudamel has introduced classical music to new audiences around the world and has helped to provide access to the arts for countless people in underserved communities. As the Music & Artistic Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, now in his twelfth season, Dudamel’s bold programming and expansive vision led The New York Times to herald the LA Phil as “the most important orchestra in America – period.” With the COVID-19 global pandemic shutting down the majority of live performances, Dudamel has committed even more time and energy to his mission of bringing music to young people across the globe, firm in his belief that the arts play an essential role in creating a more just, peaceful, and integrated society. While quarantining in Los Angeles, he hosted a new radio program from his living room entitled “At Home with Gustavo,” sharing personal stories and musical selections as a way to bring people together during a time of isolation. The program was broadcast locally as well as internationally in both English and Spanish, with guest co-hosts including, among others, composer John Williams, his wife, actress María Valverde. Dudamel also participated in Global Citizen’s Global Goal: Unite For Our Future TV fundraising special, giving a socially-distanced performance from the Hollywood Bowl with the LA Phil and YOLA (Youth Orchestra Los Angeles). -

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano by Maria Payan, M.M., B.M. A Thesis In Music Performance Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved Dr. Lisa Garner Santa Chair of Committee Dr. Keith Dye Dr. David Shea Dominick Casadonte Interim Dean of the Graduate School May 2013 Copyright 2013, Maria Payan Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have started without the extraordinary help and encouragement of Dr. Lisa Garner Santa. The education, time, and support she gave me during my studies at Texas Tech University convey her devotion to her job. I have no words to express my gratitude towards her. In addition, this project could not have been finished without the immense help and patience of Dr. Keith Dye. For his generosity in helping me organize and edit this project, I thank him greatly. Finally, I would like to give my dearest gratitude to Donna Hogan. Without her endless advice and editing, this project would not have been at the level it is today. ii Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. ii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ -

RCM Clarinet Syllabus / 2014 Edition

FHMPRT396_Clarinet_Syllabi_RCM Strings Syllabi 14-05-22 2:23 PM Page 3 Cla rinet SYLLABUS EDITION Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. The Royal Conservatory will continue to be an active partner and supporter in your musical journey of self-expression and self-discovery. -

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series

Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series Frank Morelli, Bassoon Behind every Juilliard artist is all of Juilliard —including you. With hundreds of dance, drama, and music performances, Juilliard is a wonderful place. When you join one of our membership programs, you become a part of this singular and celebrated community. by Claudio Papapietro Photo of cellist Khari Joyner Photo by Claudio Papapietro Become a member for as little as $250 Join with a gift starting at $1,250 and and receive exclusive benefits, including enjoy VIP privileges, including • Advance access to tickets through • All Association benefits Member Presales • Concierge ticket service by telephone • 50% discount on ticket purchases and email • Invitations to special • Invitations to behind-the-scenes events members-only gatherings • Access to master classes, performance previews, and rehearsal observations (212) 799-5000, ext. 303 [email protected] juilliard.edu The Juilliard School presents Faculty Recital: Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jesse Brault, Conductor Jonathan Feldman, Piano Jacob Wellman, Bassoon Wednesday, January 17, 2018, 7:30pm Paul Hall Part of the Daniel Saidenberg Faculty Recital Series GIOACHINO From The Barber of Seville (1816) ROSSINI (arr. François-René Gebauer/Frank Morelli) (1792–1868) All’idea di quell metallo Numero quindici a mano manca Largo al factotum Frank Morelli and Jacob Wellman, Bassoons JOHANNES Sonata for Cello, No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 38 (1862–65) BRAHMS Allegro non troppo (1833–97) Allegro quasi menuetto-Trio Allegro Frank Morelli, Bassoon Jonathan Feldman, Piano Intermission Program continues Major funding for establishing Paul Recital Hall and for continuing access to its series of public programs has been granted by The Bay Foundation and the Josephine Bay Paul and C. -

8Th Grade Orchestra Curriculum Map

8th Grade Orchestra Curriculum Map Music Reading: Student will be able to read and perform one octave major and melodic minor scales in the keys of EbM/cm; BbM/gm; FM/dm; CM/am; GM/em; DM/bm; AM/f#m Student will be able to read and perform key changes. Student will be able to read and correctly perform accidentals and understand their duration. Student will be able to read and perform simple tenor clef selections in cello/bass; treble clef in viola Violin Students will be able to read and perform music written on upper ledger lines. Rhythm: Students will review basic time signature concepts Students will read, write and perform compound dotted rhythms, 32nd notes Students will learn and perform basic concepts of asymmetrical meter Students will review/reinforce elements of successful time signature changes Students will be able to perform with internal subdivision Students will be able to count and perform passages successfully with correct rhythms, using professional counting system. Students will be able to synchronize performance of rhythmic motives within the section. Students will be able to synchronize performance of the sections’ rhythm to the other sections of the orchestra. Pitch: Student is proficient in turning his/her own instrument with the fine tuners. Student is able to hear bottom open string of octave ring when top note is played. Students will review and reinforce tuning to perfect 5ths using the following methods: o tuning across the orchestra o listening and tuning to the 5ths on personal instrument. Student performs with good intonation within the section. -

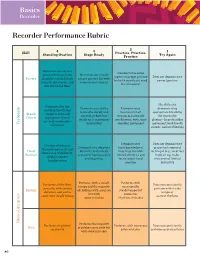

Recorder Performance Rubric

Basics Recorder Recorder Performance Rubric 2 Skill 4 3 Practice, Practice, 1 Standing Ovation Stage Ready Practice Try Again Demonstrates correct Demonstrates some posture with neck and Demonstrates mostly aspects of proper posture Does not demonstrate Posture shoulders relaxed, back proper posture but with but with significant need correct posture straight, chest open, and some inconsistencies for refinement feet flat on the floor Has difficulty Demonstrates low Demonstrates ability Demonstrates demonstrating and deep breath that to breathe deeply and inconsistent air appropriate breathing Breath supports even and control air flow, but stream, occasionally for successful Control appropriate flow of steady air is sometimes overblowing, with some playing—large shoulder air, with no shoulder Technique inconsistent shoulder movement movement, loud breath movement sounds, and overblowing Demonstrates Does not demonstrate Consistently fingers Demonstrates adequate basic knowledge of proper instrumental the notes correctly and Hand dexterity with mostly fingerings but with technique (e.g., incorrect shows ease of dexterity; Position consistent hand position limited dexterity and hand on top, holes displays correct and fingerings inconsistent hand not covered, limited hand position position dexterity) Performs with a steady Performs with Performs all rhythms Does not consistently tempo and the majority occasionally correctly, with correct perform with steady Rhythm of rhythms with accuracy steady tempo but duration, and with a tempo or but -

Transfer Learning for Piano Sustain-Pedal Detection

Transfer Learning for Piano Sustain-Pedal Detection Beici Liang, Gyorgy¨ Fazekas and Mark Sandler Centre for Digital Music, Queen Mary University of London London, United Kingdom Email: fbeici.liang,g.fazekas,[email protected] Abstract—Detecting piano pedalling techniques in polyphonic music remains a challenging task in music information retrieval. While other piano-related tasks, such as pitch estimation and onset detection, have seen improvement through applying deep learning methods, little work has been done to develop deep learning models to detect playing techniques. In this paper, we propose a transfer learning approach for the detection of sustain- pedal techniques, which are commonly used by pianists to enrich the sound. In the source task, a convolutional neural network (CNN) is trained for learning spectral and temporal contexts when the sustain pedal is pressed using a large dataset generated by a physical modelling virtual instrument. The CNN is designed Melspectrogram and experimented through exploiting the knowledge of piano acoustics and physics. This can achieve an accuracy score of MIDI & sensor 0 127 0.98 in the validation results. In the target task, the knowledge learned from the synthesised data can be transferred to detect the Fig. 1. Different representations of the same note played without (first note) or sustain pedal in acoustic piano recordings. A concatenated feature with (second note) the sustain pedal, including music score, melspectrogram vector using the activations of the trained convolutional layers is and messages from MIDI or sensor data. extracted from the recordings and classified into frame-wise pedal press or release. We demonstrate the effectiveness of our method in acoustic piano recordings of Chopin’s music. -

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter SUN / OCT 21 / 11:00 AM Michele Zukovsky Robert deMaine CLARINET CELLO Robert Davidovici Kevin Fitz-Gerald VIOLIN PIANO There will be no intermission. Please join us after the performance for refreshments and a conversation with the performers. PROGRAM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Trio in B-flat major, Op. 11 I. Allegro con brio II. Adagio III. Tema: Pria ch’io l’impegno. Allegretto Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) Quartet for the End of Time (1941) I. Liturgie de cristal (“Crystal liturgy”) II. Vocalise, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Vocalise, for the Angel who announces the end of time”) III. Abîme des oiseau (“Abyss of birds”) IV. Intermède (“Interlude”) V. Louange à l'Éternité de Jésus (“Praise to the eternity of Jesus”) VI. Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes (“Dance of fury, for the seven trumpets”) VII. Fouillis d'arcs-en-ciel, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Tangle of rainbows, for the Angel who announces the end of time) VIII. Louange à l'Immortalité de Jésus (“Praise to the immortality of Jesus”) This series made possible by a generous gift from Barbara Herman. PERFORMANCES MAGAZINE 20 ABOUT THE ARTISTS MICHELE ZUKOVSKY, clarinet, is an also produced recordings of several the Australian National University. American clarinetist and longest live performances by Zukovsky, The Montréal La Presse said that, serving member of the Los Angeles including the aforementioned Williams “Robert Davidovici is a born violinist Philharmonic Orchestra, serving Clarinet Concerto. Alongside her in the most complete sense of from 1961 at the age of 18 until her busy performing schedule, Zukovsky the word.” In October 2013, he retirement on December 20, 2015. -

The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1980 The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance. Malcolm Eugene Beauchamp Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Beauchamp, Malcolm Eugene, "The Application of Bel Canto Concepts and Principles to Trumpet Pedagogy and Performance." (1980). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3474. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3474 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Voice Dysphoria and the Transgender and Genderqueer Singer

What the Fach? Voice Dysphoria and the Transgender and Genderqueer Singer Loraine Sims, DMA, Associate Professor, Edith Killgore Kirkpatrick Professor of Voice, LSU 2018 NATS National Conference Las Vegas Introduction One size does not fit all! Trans Singers are individuals. There are several options for the singing voice. Trans woman (AMAB, MtF, M2F, or trans feminine) may prefer she/her/hers o May sing with baritone or tenor voice (with or without voice dysphoria) o May sing head voice and label as soprano or mezzo Trans man (AFAB, FtM, F2M, or trans masculine) may prefer he/him/his o No Testosterone – Probably sings mezzo soprano or soprano (with or without voice dysphoria) o After Testosterone – May sing tenor or baritone or countertenor Third Gender or Gender Fluid (Non-binary or Genderqueer) – prefers non-binary pronouns they/them/their or something else (You must ask!) o May sing with any voice type (with or without voice dysphoria) Creating a Gender Neutral Learning Environment Gender and sex are not synonymous terms. Cisgender means that your assigned sex at birth is in agreement with your internal feeling about your own gender. Transgender means that there is disagreement between the sex you were assigned at birth and your internal gender identity. There is also a difference between your gender identity and your gender expression. Many other terms fall under the trans umbrella: Non-binary, gender fluid, genderqueer, and agender, etc. Remember that pronouns matter. Never assume. The best way to know what pronouns someone prefers for themselves is to ask. In addition to she/her/hers and he/him/his, it is perfectly acceptable to use they/them/their for a single individual if that is what they prefer.