Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

Unit 10.2 the Physics of Music Objectives Notes on a Piano

Unit 10.2 The Physics of Music Teacher: Dr. Van Der Sluys Objectives • The Physics of Music – Strings – Brass and Woodwinds • Tuning - Beats Notes on a Piano Key Note Frquency (Hz) Wavelength (m) 52 C 524 0.637 51 B 494 0.676 50 A# or Bb 466 0.717 49 A 440 0.759 48 G# or Ab 415 0.805 47 G 392 0.852 46 F# or Gb 370 0.903 45 F 349 0.957 44 E 330 1.01 43 D# or Eb 311 1.07 42 D 294 1.14 41 C# or Db 277 1.21 40 C (middle) 262 1.27 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_key_frequencies 1 Vibrating Strings - Fundamental and Overtones A vibration in a string can L = 1/2 λ1 produce a standing wave. L = λ Usually a vibrating string 2 produces a sound whose L = 3/2 λ3 frequency in most cases is constant. Therefore, since L = 2 λ4 frequency characterizes the pitch, the sound produced L = 5/2 λ5 is a constant note. Vibrating L = 3 λ strings are the basis of any 6 string instrument like guitar, L = 7/2 λ7 cello, or piano. For the fundamental, λ = 2 L where Vibration, standing waves in a string, L is the length of the string. The fundamental and the first 6 overtones which form a harmonic series http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vibrating_string Length of Piano Strings The highest key on a piano corresponds to a frequency about 150 times that of the lowest key. If the string for the highest note is 5.0 cm long, how long would the string for the lowest note have to be if it had the same mass per unit length and the same tension? If v = fλ, how are the frequencies and length of strings related? Other String Instruments • All string instruments produce sound from one or more vibrating strings, transferred to the air by the body of the instrument (or by a pickup in the case of electronically- amplified instruments). -

8Th Grade Orchestra Curriculum Map

8th Grade Orchestra Curriculum Map Music Reading: Student will be able to read and perform one octave major and melodic minor scales in the keys of EbM/cm; BbM/gm; FM/dm; CM/am; GM/em; DM/bm; AM/f#m Student will be able to read and perform key changes. Student will be able to read and correctly perform accidentals and understand their duration. Student will be able to read and perform simple tenor clef selections in cello/bass; treble clef in viola Violin Students will be able to read and perform music written on upper ledger lines. Rhythm: Students will review basic time signature concepts Students will read, write and perform compound dotted rhythms, 32nd notes Students will learn and perform basic concepts of asymmetrical meter Students will review/reinforce elements of successful time signature changes Students will be able to perform with internal subdivision Students will be able to count and perform passages successfully with correct rhythms, using professional counting system. Students will be able to synchronize performance of rhythmic motives within the section. Students will be able to synchronize performance of the sections’ rhythm to the other sections of the orchestra. Pitch: Student is proficient in turning his/her own instrument with the fine tuners. Student is able to hear bottom open string of octave ring when top note is played. Students will review and reinforce tuning to perfect 5ths using the following methods: o tuning across the orchestra o listening and tuning to the 5ths on personal instrument. Student performs with good intonation within the section. -

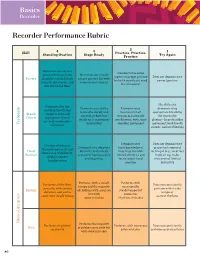

Recorder Performance Rubric

Basics Recorder Recorder Performance Rubric 2 Skill 4 3 Practice, Practice, 1 Standing Ovation Stage Ready Practice Try Again Demonstrates correct Demonstrates some posture with neck and Demonstrates mostly aspects of proper posture Does not demonstrate Posture shoulders relaxed, back proper posture but with but with significant need correct posture straight, chest open, and some inconsistencies for refinement feet flat on the floor Has difficulty Demonstrates low Demonstrates ability Demonstrates demonstrating and deep breath that to breathe deeply and inconsistent air appropriate breathing Breath supports even and control air flow, but stream, occasionally for successful Control appropriate flow of steady air is sometimes overblowing, with some playing—large shoulder air, with no shoulder Technique inconsistent shoulder movement movement, loud breath movement sounds, and overblowing Demonstrates Does not demonstrate Consistently fingers Demonstrates adequate basic knowledge of proper instrumental the notes correctly and Hand dexterity with mostly fingerings but with technique (e.g., incorrect shows ease of dexterity; Position consistent hand position limited dexterity and hand on top, holes displays correct and fingerings inconsistent hand not covered, limited hand position position dexterity) Performs with a steady Performs with Performs all rhythms Does not consistently tempo and the majority occasionally correctly, with correct perform with steady Rhythm of rhythms with accuracy steady tempo but duration, and with a tempo or but -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

Musical Piano Performance by the ACT Hand

2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation Shanghai International Conference Center May 9-13, 2011, Shanghai, China Musical Piano Performance by the ACT Hand Ada Zhang1;2, Mark Malhotra3, Yoky Matsuoka3 Department of Bioengineering1, Department of Music2, Department of Computer Science and Engineering3 University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Abstract— In the past, the music community conducted research on what makes music more musical or expressive. Much of this work has focused on the manipulation of phras- ing, articulation and rubato to make music more expressive. However, it has been difficult to study neuromuscular control used by experts to create such musical music. This paper took a first step toward this effort by using the Anatomically Correct Testbed (ACT) Robotic Hand to mimic the way expert humans play when they are instructed to perform “musically” or “robotically.” Results from 22 human subjects showed that musical expression contained a larger range of dynamics and different articulation than robotic expression, while there was no difference in the use of rubato. The ACT Hand was controlled to the level of precision that allowed the replication of expert expressive performance. Its performance was then rated by 17 human listeners against music played by a human expert to show that the ACT Hand could play as musically as an expert human. Furthermore, articulation, phrasing, and Fig. 1. The Anatomically Correct Testbed Hand rubato were tested in isolation to determine the importance of articulation over phrasing and rubato. This type of study will lead to understanding how to implement future robots to and legs to depress the pedals. -

Natural Trumpet Music and the Modern Performer A

NATURAL TRUMPET MUSIC AND THE MODERN PERFORMER A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Laura Bloss December, 2012 NATURAL TRUMPET MUSIC AND THE MODERN PERFORMER Laura Bloss Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________ _________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Chand Midha _________________________ _________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. Scott Johnston Dr. George R. Newkome _________________________ _________________________ School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii ABSTRACT The Baroque Era can be considered the “golden age” of trumpet playing in Western Music. Recently, there has been a revival of interest in Baroque trumpet works, and while the research has grown accordingly, the implications of that research require further examination. Musicians need to be able to give this factual evidence a context, one that is both modern and historical. The treatises of Cesare Bendinelli, Girolamo Fantini, and J.E. Altenburg are valuable records that provide insight into the early development of the trumpet. There are also several important modern resources, most notably by Don Smithers and Edward Tarr, which discuss the historical development of the trumpet. One obstacle for modern players is that the works of the Baroque Era were originally played on natural trumpet, an instrument that is now considered a specialty rather than the standard. Trumpet players must thus find ways to reconcile the inherent differences between Baroque and current approaches to playing by combining research from early treatises, important trumpet publications, and technical and philosophical input from performance practice essays. -

Musicians Column—Aspects of Musicality

Musicians Column—Aspects of Musicality by Martha Edwards In this article, I’m going to talk about a simple thing that you can do to make you, your band mates, and your dance community fall in love with the music that you make. It’s called phrasing. Yup, phrasing. Musical phrasing is a lot like verbal phrasing. Sentences start somewhere and end somewhere, just like music. Sometimes they start soft, and grow and grow until they END! SOMETIMES they start big and taper off at the end. Sometimes they grow and get BIG and then taper off at the end. But a lot of people never notice that music does the same thing, that it comes from somewhere and goes somewhere. When you help it do that, you’re really sending a musical experience to your audience. Otherwise, you’re just typing. What do I mean by typing? I mean that, if all you do is play the notes, one after another, at the same intensity from beginning to end, you could play the notes perfectly, but your playing would be boring. You wouldn’t be shaping the phrase, you would just be sending out a kind of telegraph message with no emotion attached. I think it happens because playing music is hard, and it’s a big challenge just to be able to play the notes of a tune at all. When you finally get the notes of a tune, one after another, it’s a kind of victory. But don’t stop with just the notes. Learn to play musically! photo of Miranda Arana, Jonathan Jensen and Martha Edwards (courtesy Childgrove Country Dancers, St. -

A Handbook of Cello Technique for Performers

CELLO MAP: A HANDBOOK OF CELLO TECHNIQUE FOR PERFORMERS AND COMPOSERS By Ellen Fallowfield A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Many new sounds and new instrumental techniques have been introduced into music literature since 1950. The popular approach to support developments in modern instrumental technique is the catalogue or notation guide, which has led to isolated special effects. Several authors of handbooks of technique have pointed to an alternative, strategic, scientific approach to technique as an ideological ideal. I have adopted this approach more fully than before and applied it to the cello for the first time. This handbook provides a structure for further research. In this handbook, new techniques are presented alongside traditional methods and a ‘global technique’ is defined, within which every possible sound-modifying action is considered as a continuous scale, upon which as yet undiscovered techniques can also be slotted. -

Multiphonics of the Grand Piano – Timbral Composition and Performance with Flageolets

Multiphonics of the Grand Piano – Timbral Composition and Performance with Flageolets Juhani VESIKKALA Written work, Composition MA Department of Classical Music Sibelius Academy / University of the Arts, Helsinki 2016 SIBELIUS-ACADEMY Abstract Kirjallinen työ Title Number of pages Multiphonics of the Grand Piano - Timbral Composition and Performance with Flageolets 86 + appendices Author(s) Term Juhani Topias VESIKKALA Spring 2016 Degree programme Study Line Sävellys ja musiikinteoria Department Klassisen musiikin osasto Abstract The aim of my study is to enable a broader knowledge and compositional use of the piano multiphonics in current music. This corpus of text will benefit pianists and composers alike, and it provides the answers to the questions "what is a piano multiphonic", "what does a multiphonic sound like," and "how to notate a multiphonic sound". New terminology will be defined and inaccuracies in existing terminology will be dealt with. The multiphonic "mode of playing" will be separated from "playing technique" and from flageolets. Moreover, multiphonics in the repertoire are compared from the aspects of composition and notation, and the portability of multiphonics to the sounds of other instruments or to other mobile playing modes of the manipulated grand piano are examined. Composers tend to use multiphonics in a different manner, making for differing notational choices. This study examines notational choices and proposes a notation suitable for most situations, and notates the most commonly produceable multiphonic chords. The existence of piano multiphonics will be verified mathematically, supported by acoustic recordings and camera measurements. In my work, the correspondence of FFT analysis and hearing will be touched on, and by virtue of audio excerpts I offer ways to improve as a listener of multiphonics. -

Teaching Phrase and Musical Artistry Through a Laban Based Pedagogy a Laban Based Pedagogy

Workshop In Teaching Musicianship and Artistry Through Movement and Kinesthetic Workshop In TeachingA Mwaurseincieasns sohfi pH aonwd S Aourntids tMryo Tvehsr Fouogrhw aMrdo vement and Kinesthetic Awareness of How So und Moves Forward Teaching Phrase and Musical Artistry through Teaching Phrase and Musical Artistry through A Laban Based Pedagogy A Laban Based Pedagogy James Jordan, Ph.D. D.Mus James Jordan, Ph.D. D.Mus Professor and Senior Conductor, Westminster Choir College Conductor and Artistic Director of The Same Stream (Thesamestreamchoir.com) Professor and Senior Conductor, Westminster Choir College Choral Consultant-We-music.com Conductor and Artistic Director of The Same Stream (Thesamestreamchoir.com) Co-Director-The Choral Institute at Oxford (rider.edu/oxford) ChoralGiamusic.com/Jordan Consultant-We-music.com Co-Director-The ChoralTwitter@Jevoke Institute at Ox ford (rider.edu/oxford) Giamusic.com/Jordan Twitter@Jevoke The Principles of Artistry Through the Door of Kinesthetic Learning This space-memory-combined with our continuous process of anticipation, is the source of our sensing time as time, and ourselves as ourselves (p.164) Carlo Rovelli In The Order of Time Few people will realize that a page of musical notes is to a great extent a description or prescription of bodilly motivations or of the way how to move your muscles, limbs and breathing organs…in order to produce certain effects (p.39). Rudolf Laban In Karen K. Bradley Rudolf Laban Musicians who do not audiate shifting weight perform with displaced energy (p.190) Edwin Gordon In Learning Sequences in Music (2012) The rhythm texture of music…In its total effect on the listener, the rhythm of music derives from two main sources, melodic and harmonic (p.123) It is assumed that the conceptions meter and rhythm are understood. -

The Perception of Movement Through Musical Sound: Towards A

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 7-10-2013 The eP rception of Movement through Musical Sound: Towards a Dynamical Systems Theory of Music Performance Alexander P. Demos University of Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Demos, Alexander P., "The eP rception of Movement through Musical Sound: Towards a Dynamical Systems Theory of Music Performance" (2013). Doctoral Dissertations. 155. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/155 The Perception of Movement through Musical Sound: Towards a Dynamical Systems Theory of Music Performance Alexander Pantelis Demos, PhD University of Connecticut, 2013 Performers’ ancillary body movements, which are generally thought to support sound- production, appear to be related to musical structure and musical expression. Uncovering systematic relationships has, however, been difficult. Researchers have used the framework of embodied gestures, adapted from language research, to categorize and analyze performer’s movements. I have taken a different approach, conceptualizing ancillary movements as continuous actions in space-time within a dynamical systems framework. The framework predicts that the movements of the performer will be complexly, but systematically, related to the musical movement and that listeners will be able to hear both the metaphorical motion implied by the musical structure and the real movements of the performer. In three experiments, I adapted a set of statistical, time-series, and dynamical systems tools to music performance research to examine these predictions. In Experiment 1, I used force plate measurements to examine the postural sway of two trombonists playing two solo pieces with different musical structures in different expressive styles (normal, expressive, non-expressive).