Musical Piano Performance by the ACT Hand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano by Maria Payan, M.M., B.M. A Thesis In Music Performance Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved Dr. Lisa Garner Santa Chair of Committee Dr. Keith Dye Dr. David Shea Dominick Casadonte Interim Dean of the Graduate School May 2013 Copyright 2013, Maria Payan Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have started without the extraordinary help and encouragement of Dr. Lisa Garner Santa. The education, time, and support she gave me during my studies at Texas Tech University convey her devotion to her job. I have no words to express my gratitude towards her. In addition, this project could not have been finished without the immense help and patience of Dr. Keith Dye. For his generosity in helping me organize and edit this project, I thank him greatly. Finally, I would like to give my dearest gratitude to Donna Hogan. Without her endless advice and editing, this project would not have been at the level it is today. ii Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. ii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ -

8Th Grade Orchestra Curriculum Map

8th Grade Orchestra Curriculum Map Music Reading: Student will be able to read and perform one octave major and melodic minor scales in the keys of EbM/cm; BbM/gm; FM/dm; CM/am; GM/em; DM/bm; AM/f#m Student will be able to read and perform key changes. Student will be able to read and correctly perform accidentals and understand their duration. Student will be able to read and perform simple tenor clef selections in cello/bass; treble clef in viola Violin Students will be able to read and perform music written on upper ledger lines. Rhythm: Students will review basic time signature concepts Students will read, write and perform compound dotted rhythms, 32nd notes Students will learn and perform basic concepts of asymmetrical meter Students will review/reinforce elements of successful time signature changes Students will be able to perform with internal subdivision Students will be able to count and perform passages successfully with correct rhythms, using professional counting system. Students will be able to synchronize performance of rhythmic motives within the section. Students will be able to synchronize performance of the sections’ rhythm to the other sections of the orchestra. Pitch: Student is proficient in turning his/her own instrument with the fine tuners. Student is able to hear bottom open string of octave ring when top note is played. Students will review and reinforce tuning to perfect 5ths using the following methods: o tuning across the orchestra o listening and tuning to the 5ths on personal instrument. Student performs with good intonation within the section. -

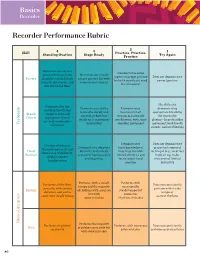

Recorder Performance Rubric

Basics Recorder Recorder Performance Rubric 2 Skill 4 3 Practice, Practice, 1 Standing Ovation Stage Ready Practice Try Again Demonstrates correct Demonstrates some posture with neck and Demonstrates mostly aspects of proper posture Does not demonstrate Posture shoulders relaxed, back proper posture but with but with significant need correct posture straight, chest open, and some inconsistencies for refinement feet flat on the floor Has difficulty Demonstrates low Demonstrates ability Demonstrates demonstrating and deep breath that to breathe deeply and inconsistent air appropriate breathing Breath supports even and control air flow, but stream, occasionally for successful Control appropriate flow of steady air is sometimes overblowing, with some playing—large shoulder air, with no shoulder Technique inconsistent shoulder movement movement, loud breath movement sounds, and overblowing Demonstrates Does not demonstrate Consistently fingers Demonstrates adequate basic knowledge of proper instrumental the notes correctly and Hand dexterity with mostly fingerings but with technique (e.g., incorrect shows ease of dexterity; Position consistent hand position limited dexterity and hand on top, holes displays correct and fingerings inconsistent hand not covered, limited hand position position dexterity) Performs with a steady Performs with Performs all rhythms Does not consistently tempo and the majority occasionally correctly, with correct perform with steady Rhythm of rhythms with accuracy steady tempo but duration, and with a tempo or but -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

Musicians Column—Aspects of Musicality

Musicians Column—Aspects of Musicality by Martha Edwards In this article, I’m going to talk about a simple thing that you can do to make you, your band mates, and your dance community fall in love with the music that you make. It’s called phrasing. Yup, phrasing. Musical phrasing is a lot like verbal phrasing. Sentences start somewhere and end somewhere, just like music. Sometimes they start soft, and grow and grow until they END! SOMETIMES they start big and taper off at the end. Sometimes they grow and get BIG and then taper off at the end. But a lot of people never notice that music does the same thing, that it comes from somewhere and goes somewhere. When you help it do that, you’re really sending a musical experience to your audience. Otherwise, you’re just typing. What do I mean by typing? I mean that, if all you do is play the notes, one after another, at the same intensity from beginning to end, you could play the notes perfectly, but your playing would be boring. You wouldn’t be shaping the phrase, you would just be sending out a kind of telegraph message with no emotion attached. I think it happens because playing music is hard, and it’s a big challenge just to be able to play the notes of a tune at all. When you finally get the notes of a tune, one after another, it’s a kind of victory. But don’t stop with just the notes. Learn to play musically! photo of Miranda Arana, Jonathan Jensen and Martha Edwards (courtesy Childgrove Country Dancers, St. -

Teaching Phrase and Musical Artistry Through a Laban Based Pedagogy a Laban Based Pedagogy

Workshop In Teaching Musicianship and Artistry Through Movement and Kinesthetic Workshop In TeachingA Mwaurseincieasns sohfi pH aonwd S Aourntids tMryo Tvehsr Fouogrhw aMrdo vement and Kinesthetic Awareness of How So und Moves Forward Teaching Phrase and Musical Artistry through Teaching Phrase and Musical Artistry through A Laban Based Pedagogy A Laban Based Pedagogy James Jordan, Ph.D. D.Mus James Jordan, Ph.D. D.Mus Professor and Senior Conductor, Westminster Choir College Conductor and Artistic Director of The Same Stream (Thesamestreamchoir.com) Professor and Senior Conductor, Westminster Choir College Choral Consultant-We-music.com Conductor and Artistic Director of The Same Stream (Thesamestreamchoir.com) Co-Director-The Choral Institute at Oxford (rider.edu/oxford) ChoralGiamusic.com/Jordan Consultant-We-music.com Co-Director-The ChoralTwitter@Jevoke Institute at Ox ford (rider.edu/oxford) Giamusic.com/Jordan Twitter@Jevoke The Principles of Artistry Through the Door of Kinesthetic Learning This space-memory-combined with our continuous process of anticipation, is the source of our sensing time as time, and ourselves as ourselves (p.164) Carlo Rovelli In The Order of Time Few people will realize that a page of musical notes is to a great extent a description or prescription of bodilly motivations or of the way how to move your muscles, limbs and breathing organs…in order to produce certain effects (p.39). Rudolf Laban In Karen K. Bradley Rudolf Laban Musicians who do not audiate shifting weight perform with displaced energy (p.190) Edwin Gordon In Learning Sequences in Music (2012) The rhythm texture of music…In its total effect on the listener, the rhythm of music derives from two main sources, melodic and harmonic (p.123) It is assumed that the conceptions meter and rhythm are understood. -

The Perception of Movement Through Musical Sound: Towards A

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 7-10-2013 The eP rception of Movement through Musical Sound: Towards a Dynamical Systems Theory of Music Performance Alexander P. Demos University of Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Demos, Alexander P., "The eP rception of Movement through Musical Sound: Towards a Dynamical Systems Theory of Music Performance" (2013). Doctoral Dissertations. 155. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/155 The Perception of Movement through Musical Sound: Towards a Dynamical Systems Theory of Music Performance Alexander Pantelis Demos, PhD University of Connecticut, 2013 Performers’ ancillary body movements, which are generally thought to support sound- production, appear to be related to musical structure and musical expression. Uncovering systematic relationships has, however, been difficult. Researchers have used the framework of embodied gestures, adapted from language research, to categorize and analyze performer’s movements. I have taken a different approach, conceptualizing ancillary movements as continuous actions in space-time within a dynamical systems framework. The framework predicts that the movements of the performer will be complexly, but systematically, related to the musical movement and that listeners will be able to hear both the metaphorical motion implied by the musical structure and the real movements of the performer. In three experiments, I adapted a set of statistical, time-series, and dynamical systems tools to music performance research to examine these predictions. In Experiment 1, I used force plate measurements to examine the postural sway of two trombonists playing two solo pieces with different musical structures in different expressive styles (normal, expressive, non-expressive). -

Studies of Music Performance (J

STUDIES OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE (J. Sundberg, editor) Papers given at a seminar organized by the Music Acoustics Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music Publications issued by the Royal Swedish Academy of Music No. 39 1983 STUDIES OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE (J. Sundberg, editor) Papers given at a seminar organized by the Music Acoustics Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music Publications issued by the Royal Swedish Academy of Music No. 39 1983 IBSN 91-85428-30-2 O 1983 by the Royal Swedish Academy of Music, Stockholm, Sweden ADEBE Reklam & Tryckservice, Stockholm, Sweden TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface H.C. Longuet-Higgins and C.S. Lee: The Rhythmic Interpretation of Monophonic Music I. Bengtsson, A. Gabrielsson: Analysis and synthesis of musical rhythm J. Sundberg, L. Frydb, A. Askenfelt: What tells you the player is musical? An analysis-by-synthesis study of music performance M. Clynes Expressive microstructure in music, linked to living qualities Lists of sound examples PREFACE On October 23, 1982, the Music Acoustics Committee of the Royal Swe- dish Academy of Music arranged the eighth full day public seminar which was devoted to various aspects of analyis of musical performance. Two foreign speakers, Manfred Clynes from the New South Wales Conservatorium of Music, Sydney, Australia, and Christopher Longuet-Higgins, University of Sussex, England. Also, professor Ingmar Bengtsson and docent Alf Gabrielsson of the Uppsala University and myself reported on our works in this area. Written versions of these papers are now published in the present volume. As with previous issues in this series of books published by the Academy on various topics in the field of music acoustics we are fortunate enough to offer sound illustrations on the grammophone records enclosed, which still remains a remarkably rare arrangement in books dealing with sound. -

CONCEPTS Elements of Music SKILLS Performance MUSIC

BOE Approval _____ DEPARTMENT COURSE SEQUENCE: 5th Grade General Music TOWNSHIP OF OCEAN SCHOOLS CONCEPTS SKILLS MUSIC APPRECIATION Elements of Music Performance History and Culture Rhythms Singing Instruments Beat (Meter and Time Signatures) Solo Individual Instruments and Instrument Families Music Symbols Ensemble Categorize Instruments Visually and Aurally Rhythmic Notation Multiple-Part Harmony Music Careers Pitch/Melody Playing Conductor, Composer, Performer, etc. Melodic Contour and Direction Body Percussion Melodic Notation on the Music Staff Playing on Instruments Styles of Music Describing Various Genres of Music Harmony Moving Periods of Music History Rounds Choreography Ostinatos Interpretive Dance Multicultural Partner Songs Songs Listening Dance Dynamics Listening Skills Ethnic Instruments Loud and Soft Critique Audience Etiquette Music Technology Tempos Evolution of Music Through the Ages Fast and Slow Creating Methods of Recording, Listening, and Creating Improvising with Instruments Music Form Improvising Dance and Movement Same or Different Composing Simple Patterns and Phrases Musical Phrasing Interpretation and Dramatization Tone Color Vocal Timbre Instrument Timbre Revised June 2009 Topic: Elements of Music By the end of 5th Grade Essential Questions • How do we know how many beats are in a measure of music? • How does the melodic contour and direction flow through the music? • What symbols are used to represent the dynamic levels in music? • Can you describe how tempos vary in music? • Can you describe how music is -

2016 Vce Music Teachers' Conference Session Notes

Association of Music Educators 2016 VCE MUSIC TEACHERS’ CONFERENCE SESSION NOTES VCE CONFERENCE 2016 SATURDAY 27 FEBRUARY SESSION 1 MUSIC STYLE AND COMPOSITION EAT report Pip Robinson EAT process Mark McSherry Scaffolding Outcome 1 Anna van Veldhuisen I hear, I see – Outcomes 2 and 3 Mandy Stefanakis Context as part of Outcome 2 Matt Pankhurst Transition to 2017 Helen Champion SESSION 2. MUSIC INVESTIGATION MUSIC INVESTIGATION PLENARY SESSION Messages from 2015 and transitioning to 2017 Helen Champion Outcome 3 – Performance Rod Marshall Chief Assessor’s report Outcome 1 – Investigation Lynne Morton State Reviewer’s report Teaching strategy workshop MI:1 MI:1.1: Selecting repertoire for the end of year exam/linking with Focus Statement – Rod Marshall MI:1.3: Preparing students for composition and improvisation via a folio of works – Nick Taylor MI:1.4: Surviving and achieving in the Multi-Study Classroom – Lynne Morton Teaching strategy workshop MI:2 MI:2.1: Selecting repertoire for the end of year exam/linking with Focus Statement – Rod Marshall MI:2.2: Using the new assessment guide numbers for School Assessed Coursework. – Lynne Morton MI:2.3: A systematic approach to teaching improvisation – David Urquhart-Jones MI:2.4: Enhancing and harnessing creativity in Outcome 2: Composition – Matt Pankhurst SUNDAY 22 FEBRUARY SESSION 3. MUSIC PERFORMANCE MUSIC PERFORMANCE PLENARY SESSION Messages from 2015 and transitioning to 2017 Helen Champion Outcome 3 Examiner’s report Barry Fletcher Outcome 2 State reviewers report David Graham Outcome -

Alexander Armstrong, Launch Concert, Diamond Fund for Choristers, St Paul’S Cathedral, 27 April 2016

Alexander Armstrong, launch concert, Diamond Fund for Choristers, St Paul’s Cathedral, 27 April 2016 Your Royal Highness, my Lords, Ladies and Gentlemen: good evening! What a spectacular event this is and what a great honour it is to be a part of it. I am thrilled to be here. Moreover, I am delighted to have the opportunity to talk to you briefly about the tremendous privilege of choristership: the single greatest leg-up a child can be given in life. Now, I know that sounds overblown and, yes, it is a bold claim but the more I think about it the truer I realise it is. Someone made the mistake of asking me during an interview the other day what the benefits are of being a chorister. Well that interview ended up overrunning by half of an hour and I was barely halfway through my list. The most obvious benefit is the total submersion in music. This is a ‘compleat’ musical education by process of osmosis. When you come to hang up your cassock for the final time at the age of 13 you will – without even having realised it was happening because you were just having a lovely time singing – have personal experience of every age and fashion of music from the ancient fauxbourdons of plainchant, to the exciting knotty textures of anthems so contemporary that the composers themselves might very well have conducted you. You will have breathed life into everyone from Buxtehude to Britten to Bach to Bridge to Bax to Brahms to Byrd to Bairstow to Bruckner to Bliss (and that’s just the Bs I can think of off the top of my head).