A Handbook of Cello Technique for Performers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

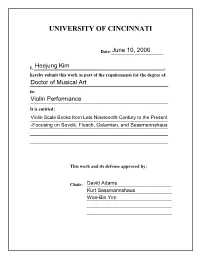

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ ViolinScaleBooks fromLateNineteenth-Centurytothe Present -FocusingonSevcik,Flesch,Galamian,andSassmannshaus Adocumentsubmittedtothe DivisionofGraduateStudiesandResearchofthe UniversityofCincinnati Inpartialfulfillmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeof DOCTORAL OFMUSICALARTS inViolinPerformance 2006 by HeejungKim B.M.,Seoul NationalUniversity,1995 M.M.,TheUniversityof Cincinnati,1999 Advisor:DavidAdams Readers:KurtSassmannshaus Won-BinYim ABSTRACT Violinists usuallystart practicesessionswithscale books,andtheyknowthe importanceofthem asatechnical grounding.However,performersandstudents generallyhavelittleinformation onhowscale bookshave beendevelopedandwhat detailsaredifferentamongmanyscale books.Anunderstanding ofsuchdifferences, gainedthroughtheidentificationandcomparisonofscale books,canhelp eachviolinist andteacherapproacheachscale bookmoreintelligently.Thisdocumentoffershistorical andpracticalinformationforsome ofthemorewidelyused basicscalestudiesinviolin playing. Pedagogicalmaterialsforviolin,respondingtothetechnicaldemands andmusical trendsoftheinstrument , haveincreasedinnumber.Amongthem,Iwillexamineand comparethe contributionstothescale -

The Application of the Kinesthetic Sense: an Introduction of Body Awareness in Cello Pedagogy and Performance

The Application of the Kinesthetic Sense: An Introduction of Body Awareness in Cello Pedagogy and Performance A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music March 2014 by Gustavo Carpinteyro-Lara BM, University of Southern Mississippi, 2001 MM, Bowling Green State University, 2003 Committee Chair: Lee Fiser, BM Abstract This document on cello pedagogy and playing focuses on the importance of the kinesthetic sense as it relates to teaching and performance quality. William Conable, creator of body mapping, has described how the kinesthetic sense or movement sense provides information about the body’s position and size, and whether the body is moving and, if so, where and how. In addition Craig Williamson, pioneer of Somatic Integration, claims that the kinesthetic sense enables one to sense what the body is doing at any time, including muscular effort, tension, relaxation, balance, spatial orientation, distance, and proportion. Cellists can develop and awaken the kinesthetic sense in order to have conscious body awareness, and to understand that cello playing is a physical, aerobic, intellectual, and musical activity. This document describes the physical, motion, aerobic, anatomic, and kinesthetic approach to cello playing and is supported by somatic education methods, such as the Alexander Technique, Feldenkrais Method, and Yoga. By applying body awareness and kinesthesia in cello playing, cellists can have freedom, balance, ease in their movements, and an intelligent way of playing and performing. ii Copyright © 2014 by Gustavo Carpinteyro-Lara. -

Circuition: Concerto for Jazz Guitar and Orchestra

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2021 CIRCUITION: CONCERTO FOR JAZZ GUITAR AND ORCHESTRA Richard Alan Robinson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2021.166 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Robinson, Richard Alan, "CIRCUITION: CONCERTO FOR JAZZ GUITAR AND ORCHESTRA" (2021). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 178. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/178 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano

Written and Recorded Preparation Guides: Selected Repertoire from the University Interscholastic League Prescribed List for Flute and Piano by Maria Payan, M.M., B.M. A Thesis In Music Performance Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved Dr. Lisa Garner Santa Chair of Committee Dr. Keith Dye Dr. David Shea Dominick Casadonte Interim Dean of the Graduate School May 2013 Copyright 2013, Maria Payan Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have started without the extraordinary help and encouragement of Dr. Lisa Garner Santa. The education, time, and support she gave me during my studies at Texas Tech University convey her devotion to her job. I have no words to express my gratitude towards her. In addition, this project could not have been finished without the immense help and patience of Dr. Keith Dye. For his generosity in helping me organize and edit this project, I thank him greatly. Finally, I would like to give my dearest gratitude to Donna Hogan. Without her endless advice and editing, this project would not have been at the level it is today. ii Texas Tech University, Maria Payan, May 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. ii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ -

Unit 10.2 the Physics of Music Objectives Notes on a Piano

Unit 10.2 The Physics of Music Teacher: Dr. Van Der Sluys Objectives • The Physics of Music – Strings – Brass and Woodwinds • Tuning - Beats Notes on a Piano Key Note Frquency (Hz) Wavelength (m) 52 C 524 0.637 51 B 494 0.676 50 A# or Bb 466 0.717 49 A 440 0.759 48 G# or Ab 415 0.805 47 G 392 0.852 46 F# or Gb 370 0.903 45 F 349 0.957 44 E 330 1.01 43 D# or Eb 311 1.07 42 D 294 1.14 41 C# or Db 277 1.21 40 C (middle) 262 1.27 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_key_frequencies 1 Vibrating Strings - Fundamental and Overtones A vibration in a string can L = 1/2 λ1 produce a standing wave. L = λ Usually a vibrating string 2 produces a sound whose L = 3/2 λ3 frequency in most cases is constant. Therefore, since L = 2 λ4 frequency characterizes the pitch, the sound produced L = 5/2 λ5 is a constant note. Vibrating L = 3 λ strings are the basis of any 6 string instrument like guitar, L = 7/2 λ7 cello, or piano. For the fundamental, λ = 2 L where Vibration, standing waves in a string, L is the length of the string. The fundamental and the first 6 overtones which form a harmonic series http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vibrating_string Length of Piano Strings The highest key on a piano corresponds to a frequency about 150 times that of the lowest key. If the string for the highest note is 5.0 cm long, how long would the string for the lowest note have to be if it had the same mass per unit length and the same tension? If v = fλ, how are the frequencies and length of strings related? Other String Instruments • All string instruments produce sound from one or more vibrating strings, transferred to the air by the body of the instrument (or by a pickup in the case of electronically- amplified instruments). -

A Brief Survey of Plucked Wire-Strung Instruments, 15Th-18Th Centuries - Part Two

The Wire Connection By Andrew Hartig A Brief Survey of Plucked Wire-Strung Instruments, 15th-18th Centuries - Part Two Wire-Strung Instruments in the 16th Century ment and was used in a multitude of countries and regions. Al- Most of the wire-strung instruments from the 15th century though most players today think of the cittern as a single type of discussed in part one — such as the harpsichord, psaltery, and instrument, there were in fact many different types, each signifi- Irish harp — continued to be used on a regular basis throughout cantly different enough from the others so as to constitute separate the 16th century (and they would continue to be used into the 18th). instruments. However, almost all citterns have in common a tuning The major exception to this was the Italian cetra, which disap- characterized by the intervals of a 5th between the third and second peared at the end of the 15th century only to evolve into many dif- courses and a major 2nd between the second and first courses, and ferent forms of citterns. one or more re-entrantly tuned strings. Historically, the 16th century heralds the beginning of ma- jor shifts in thinking that led to experimentation and innovation Diatonic 6- and 7-Course Cittern in many aspects of life. Times were changing: from the discovery This was the earliest form of cittern used, possibly devel- of the “New World” that had begun at the end of the 15th century, oped from the cetra late in the 15th or early in the 16th century, and to the shifts in politics, power, religion, and gender roles that oc- it was definitely still in use into the 17th century. -

Fretted Instruments, Frets Are Metal Strips Inserted Into the Fingerboard

Fret A fret is a raised element on the neck of a stringed instrument. Frets usually extend across the full width of the neck. On most modern western fretted instruments, frets are metal strips inserted into the fingerboard. On some historical instruments and non-European instruments, frets are made of pieces of string tied around the neck. Frets divide the neck into fixed segments at intervals related to a musical framework. On instruments such as guitars, each fret represents one semitone in the standard western system, in which one octave is divided into twelve semitones. Fret is often used as a verb, meaning simply "to press down the string behind a fret". Fretting often refers to the frets and/or their system of placement. The neck of a guitar showing the nut (in the background, coloured white) Contents and first four metal frets Explanation Variations Semi-fretted instruments Fret intonation Fret wear Fret buzz Fret Repair See also References External links Explanation Pressing the string against the fret reduces the vibrating length of the string to that between the bridge and the next fret between the fretting finger and the bridge. This is damped if the string were stopped with the soft fingertip on a fretless fingerboard. Frets make it much easier for a player to achieve an acceptable standard of intonation, since the frets determine the positions for the correct notes. Furthermore, a fretted fingerboard makes it easier to play chords accurately. A disadvantage of frets is that they restrict pitches to the temperament defined by the fret positions. -

^ > Lesson 21 Q Q Q Q Q &

Lesson 21 Common Notation Articulation defines the beginning and end of each note. A slur is one type of articulation. Again, much guitar music is informal and doesn't include many articulation marks, but, here are some others that you may see. Common Articulation Markings _ > ^ . Q Q Q Q Accents - play this note louder and harder Staccato - put a short silence Legato - play very smoothly, than the ones around it. (A strong between the notes with no silence between the notes rest stroke can give a good accent.) Theory Homework Read the first two section ("Introduction" and "Physics, Harmonics, and Color" and the last section (Harmonics on Strings) of Guitar Harmonic Series at http://cnx.rice.edu/content/m11118/latest/ Guitarists play harmonics by touching the string very lightly 1. What fraction of the string is at these harmonic frets? at the correct spot while it is being plucked. What is the interval between the harmonic and the open string? On open strings*, harmonics can only be played easily at the12th, 5th, and 7th frets 12th fret______________________________________ (see theory homework): 5th fret_______________________________________ 12th fret (1/2 string) octave higher 5th fret (1/4 string) two octave higher 7th fret_______________________________________ 7th fret (1/3 string) an octave and a fifth higher 2. Analyze the chord progression on your practice page: (Write I , V and so on over each chord.) Here are the harmonics available Transpose the whole progression into a new key (your choice). on the open A string: Check your transposition by making sure that the harmonic analysis did not change. -

Recorder Performance Rubric

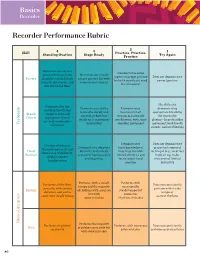

Basics Recorder Recorder Performance Rubric 2 Skill 4 3 Practice, Practice, 1 Standing Ovation Stage Ready Practice Try Again Demonstrates correct Demonstrates some posture with neck and Demonstrates mostly aspects of proper posture Does not demonstrate Posture shoulders relaxed, back proper posture but with but with significant need correct posture straight, chest open, and some inconsistencies for refinement feet flat on the floor Has difficulty Demonstrates low Demonstrates ability Demonstrates demonstrating and deep breath that to breathe deeply and inconsistent air appropriate breathing Breath supports even and control air flow, but stream, occasionally for successful Control appropriate flow of steady air is sometimes overblowing, with some playing—large shoulder air, with no shoulder Technique inconsistent shoulder movement movement, loud breath movement sounds, and overblowing Demonstrates Does not demonstrate Consistently fingers Demonstrates adequate basic knowledge of proper instrumental the notes correctly and Hand dexterity with mostly fingerings but with technique (e.g., incorrect shows ease of dexterity; Position consistent hand position limited dexterity and hand on top, holes displays correct and fingerings inconsistent hand not covered, limited hand position position dexterity) Performs with a steady Performs with Performs all rhythms Does not consistently tempo and the majority occasionally correctly, with correct perform with steady Rhythm of rhythms with accuracy steady tempo but duration, and with a tempo or but -

Insan Sesi, Vurmali Sazlar, Piyano Ve Arp

Dicle Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Kasım 2014 YIL-6 S.12 (DÜSBED) ISSN : 1308-6219 İNSAN SESİ, VURMALI ÇALGILAR, PİYANO VE ARP ÇALGILARINDAKİ YENİ İCRA TEKNİKLERİNİN 20. YÜZYILDAN GÜNÜMÜZE TARİHSEL GELİŞİMİ VE BU TEKNİKLERİN NOTASYONU Rohat CEBE ÖZ Müzisyenler, 20. yüzyılın başlarından itibaren çalgısal tekniklerin ve yeni ses kaynaklarının gelişmesinde başka hiçbir müzik tarihi döneminde olmadığı kadar önemli bir rol oynamaya başlamışlardır. Müzik besteci tarafından yazılır. Besteci yaratıcılığını, imkanlar çerçevesinde kullanacağı çalgı ya da çalgı gruplarının teknik ve fiziksel özelliklerini dikkate alarak neticelendirir. Bu bir gereksinimdir. Bu gereksinim 20. yüzyılın başlarında kültürel, siyasal ve teknolojik gelişmeler paralelinde en hareketli ve bekli de en yaratıcı seviyelere ulaşmıştır. Çalgısal tekniklerin ve yeni ses kaynaklarının gelişimi, yeni yazım ve çalım tekniklerini de beraberinde getirmiştir. Bu dönemde yaşayan besteciler eserlerinde çalgılardan o ana kadar var olan tınıların dışında farklı tınılar ve renkler elde etme arayışına girmiş, bir grup besteci de geçmişten gelen mirası ret ederek elektronik tekniklerle geliştirilmiş yeni çalgıların yapımına ve bu çalgılardan farklı sesler elde etme çabasına girmişlerdir. Yeni çalgılar yaratma fikri bir yana var olan çalgılardan yeni tınılar elde etme çabası, beraberinde klasik notalamadan farklı bir notalama biçiminin ortaya çıkmasına sebebiyet vermiştir. Bu dönemde, yeniyi arama ve bulunan yenilikleri uygulama sadece besteciler tarafından değil aynı zamanda birçok solist çalgıcının kendi çalgısının ses kabiliyetini belirleme ve keşfetmesiyle de en yüksek seviyelerine ulaşmıştır. Bu makale; başta insan sesindeki gelişmeler olmak üzere, vurmalı çalgılar, piyano ve arp çalgılarındaki yeni çalım tekniklerini, eser örnekleri ve yeni yazım tekniklerinin notalanması da gösterilerek, 20. yüzyılın ilk çeyreğinden başlayıp günümüze kadar gelen süreç içerisindeki gelişmeleri incelenmeye çalışılmıştır. -

What Is the “Ševčík Method”?

Course: CA1004 Degree Project, Master, Classical, 30hp 2020 Master's Programme in Classical Music at Edsberg Manor | 120.0 hp Department of Classical Music Supervisor: Sven Åberg Angelika Kwiatkowska What is the “Ševčík Method”? Deeper understanding of Otakar Ševčík’s excercises for violin based on the example of his 40 Variations, op. 3 Written reflection within independent project The sounding part of the project is the following recordings: Mozart – Symphony no. 39 Finale – before Mozart – Symphony no. 39 Finale – after Rossini – Overture La Gazza Ladra - before Rossini – Overture La Gazza Ladra - after Abstract In this thesis I have studied the so-called “Ševčík method” based on the example of his 40 Variations, op. 3. I’ve tried to achieve a deeper understanding of what the exercises are good for and how they work. I took a closer look at Otakar Ševčík’s life and work history, I also investigated other’s opinions and judgements of the “method” that were appearing in press and literature during the last hundred years. The practical part of my project is the experiment that I’ve put myself through. I was diligently practicing 40 Variations every day, trying to improve my technique and learn by playing how to apply those exercises in real life. As a result of this process I’ve developed my bow technique and gained better understanding of how to use Ševčík’s exercises. Keywords: Violin, technique, exercises, bow technique, right-hand technique, Ševčík I Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................