Recital of Art and Dramatic Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

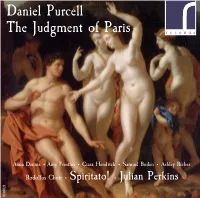

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

H O N Y Post Office Box #515 Highland Park, Illinois 60035 FAX #847-831-5577 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: Lawrence H

P O L Y P H O N Y Post Office Box #515 Highland Park, Illinois 60035 FAX #847-831-5577 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.polyphonyrecordings.com Lawrence H. Jones, Proprietor Auction Catalog #148 [Closing: Noon, Central Daylight Time; Tuesday, July 18th, 2017] Dear Fellow Record Collectors - WELCOME TO THE ONLINE VERSION OF POLYPHONY’S AUCTION CATALOG #148! All items are offered at auction; the minimum acceptable bid for each is shown at the end of its listing. The deadline for receipt of bids is Noon, Central Dayight Time; Tuesday, July 18th, 2017. SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR ONLINE: The internet version is essentially the same as the print version which is sent worldwide except that no bidsheet is provided, since all you really need to do is send me an e-mail with careful notation of your bids and the lot numbers of the items in which you are interested. A brief description of the item helps in case of mis-readings of lot numbers. If you are a new bidder and I do not have your physical address, obviously I will need it. And if you wish to authorize me to charge your winnings to a Visa, Mastercard or American Express card which I do not already have on file, I do not suggest that you send this information via e-mail since it is not very secure. You are welcome to quote an account number for me via the phone/FAX number or via the physical address shown above – or you may wait for me to send you a copy of your invoice and quote the account number by return mail. -

SCHOOL of MUSIC and DANCE the Universityoforegon Christopher S.Olin, Thursday, Mach5|7:30 P.M

ABOUT University Singers is the premier large choral ensemble on campus, with a choral tradition at the University of Oregon extending back to 1945. The University Singers perform choral music from all periods and styles, with concerts both on and off campus. Members are experienced singers representing a wide variety of majors from across campus. The University Singers frequently have the opportunity to perform with instrumental ensembles such as the University Symphony Orchestra, the Oregon Wind Ensemble, and the Eugene Symphony Orchestra. The intensive training provided by the choral program complements the core curriculum of the School of Music and Dance, and balances the broad spectrum of liberal arts disciplines offered at the University of Oregon. The University of Oregon University Singers NEWS—Chamber Choir is Germany-bound Christopher S. Olin, conductor The University of Oregon Chamber Choir is once again headed overseas, Hung-Yun Chu, accompanist this time to Marktoberdorf, Germany! The Chamber Choir is one of just ten choirs selected from around the world to participate in the 2015 Repertoire Singers Marktoberdorf International Chamber Choir Competition scheduled for May 22–27. The Chamber Choir will also tour additional German cities Cole Blume, conductor while abroad. You can be a part of this exciting moment by making a gift Sharon J. Paul, faculty advisor to send our students to Germany. For more information: 541-346-3859 Hung-Yun Chu, accompanist or music.uoregon.edu/campaign. Make sure you specify you are interested in giving to the choir’s travel fund. Chamber Choir We look forward to seeing you at our UO Choir concerts on: Sharon J. -

BY ROBERT RYAN ENDRIS Submitted to Th

REFLECTIONS OF THOREAU’S MUSIC AND PHILOSOPHY IN DOMINICK ARGENTO’S WALDEN POND (1996) BY ROBERT RYAN ENDRIS Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music in Choral Conducting, Indiana University August, 2012 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music in Choral Conducting. ___________________________________ Aaron Travers, Research Director __________________________________ Carmen-Helena Téllez, Chairperson __________________________________ William Jon Gray __________________________________ Blair Johnston ii Copyright © 2012 Robert Ryan Endris iii Acknowledgments There are many people without whose help and support this document and the completion of this degree would not be possible. First and foremost, I must acknowledge Dr. Robert S. Hatten, former professor of music theory at Indiana University and current professor of music theory at University of Texas. Dr. Hatten’s seminar “Music and the Poetic Text” sparked my interest in the relationship between poetic texts and vocal music and provided the impetus for this document. He inspired me to experience, analyze, and understand vocal music in a completely new way. I must also thank the members of my document committee. I am deeply indebted to my research director, Dr. Aaron Travers, and my chairperson, Dr. Carmen-Helena Téllez, for their efforts and willingness to lead me through this process of research, analysis, and writing. I also thank Dr. Blair Johnston and Dr. William Jon Gray for their contributions through insightful comments, observations, and suggestions. Next, I would like to express my gratitude for the support and encouragement offered by my mentors and friends. -

The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites

133 The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites Alexander McGrattan Introduction In May 1660 Charles Stuart agreed to Parliament's terms for the restoration of the monarchy and returned to London from exile in France. After eighteen years of political turmoil, which culminated in the puritanical rule of the Commonwealth, Charles II's initial priorities on his accession included re-establishing a suitable social and cultural infrastructure for his court to function. At the outbreak of the civil war in 1642, Parliament had closed the London theatres, and performances of plays were banned throughout the interregnum. In August 1660 Charles issued patents for the establishment of two theatre companies in London. The newly formed companies were patronized by royalty and an aristocracy eager to circulate again in courtly circles. This led to a shift in the focus of theatrical activity from the royal court to the playhouses. The restoration of commercial theatres had a profound effect on the musical life of London. The playhouses provided regular employment to many of its most prominent musicians and attracted others from abroad. During the final quarter of the century, by which time the audiences had come to represent a wider cross-section of London society, they provided a stimulus to the city's burgeoning concert scene. During the Restoration period—in theatrical terms, the half-century following the Restoration of the monarchy—approximately six hundred productions were presented on the London stage. The vast majority of these were spoken dramas, but almost all included a substantial amount of music, both incidental (before the start of the drama and between the acts) and within the acts, and many incorporated masques, or masque-like episodes. -

'Inspire Us Genius of the Day': Rewriting the Regent in the Birthday Ode for Queen Anne, 1703

Eighteenth-Century Music 13/1, 1–21 © Cambridge University Press, 2015 doi:10.1017/S1478570615000421 ‘inspire us genius of the day’: 1 rewriting the regent in the birthday 2 ode for queen anne, 1703 3 estelle murphy 4 ! 5 ABSTRACT 6 In 1701–1702 writer and poet Peter Anthony Motteux collaborated with composer John Eccles, Master of the King’s 7 Musick, in writing the ode for King William III’s birthday. Eccles’s autograph manuscript is listed in the British 8 library manuscript catalogue as ‘Ode for the King’s Birthday, 1703; in score by John Eccles’ and is accompanied 9 by a claim that the ode had already reached folio 10v when William died, requiring the words to be amended to 10 suit his successor, Queen Anne. A closer inspection of this manuscript reveals that much more of the ode had been 11 completed before the king’s death, and that much more than the words ‘king’ and ‘William’ was amended to suit 12 a succeeding monarch of a different gender and nationality. The work was performed before Queen Anne on her 13 birthday in 1703 and the words were published shortly afterwards. Discrepancies between the printed text and 14 that in Eccles’s score indicate that no fewer than three versions of the text were devised during the creative process. 15 These versions raise issues of authority with respect to poet and composer. A careful analysis of the manuscript’s 16 paper types and rastrology reveals a collaborative process of re-engineering that was, in fact, applied to an already 17 completed work. -

Dominick Argento

Deux-Elles DominickDominick ArgentoArgento Shadow and Substance Howard Haskin tenor ominick Argento is generally considered Classical Contemporary Composition’, in respect season, is set in the early days of Hollywood and quaver accompaniment that just occasionally a vocal composer; he is one of the leading of Frederica von Stade’s recording of his song- examines the effects of fame and the immigrant’s may remind us of Balinese gamelan patterns. DUS composers of lyric opera and one of cycle Casa Guidi on the Reference Records label. experience in America. Very different is the treatment of Samuel the most successful, in terms of performances. He was elected to the American Academy of Daniel’s ‘Care-Charmer Sleep’, a depressive The three song-cycles on this disc give some Arts and Letters in 1979, and in 1997 the lifetime A man of wide literary tastes, during the 1970s poem memorably set by Peter Warlock and indications why this should be the case. appointment of Composer Laureate to the and 1980s Argento turned increasingly to the Havergal Brian, amongst others. The agitation Minnesota Orchestra was bestowed on him. composition of song-cycles. His major of Argento’s middle section is graphically Argento was born in York, Pennsylvania and productions in this form include Six Elizabethan expressive of the poet’s tormented emotions. studied at the Peabody Conservatory from 1947 Argento has composed copious orchestral and Songs (1958), Letters from Composers (1968) for Shakespeare’s marvellous ‘When icicles hang to 1954, where his teachers included Nicholas chamber music (notably the Variations for voice and guitar, To Be Sung Upon the Water (1973) by the wall’ is set as a kind of vigorous round- Nabokov, Henry Cowell and Hugo Weisgall; this orchestra The Mask of Night, 1965) but the bulk for voice, piano and clarinet, From the Diary of dance – a good remedy to keep out the cold. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

Neo Choral II, the Dale Warland Singers, February

Walker Art Center Neo Choral II The Dale Warland Singers· February 4, 1993 Walker Art Center presents 3.I:d.Yimd.ar Neo Choral II What lack ye? What is it you will buy? The Dale Warland Singers Any points, pins or laces? 8:00 pm, Thursday, February 4, 1993 Any laces, points or pins? Come choose, come buy. Dale Warland, Conductor What is it you will buy? I have pretty poking sticks, And many other tricks. Street Cries (from ·Shoemaker·s Holiday·) (1967) ~ Dominick Argento (b. 1927) Come, cheap for your love And buy for your money A delicate ballad Of the ferret Everyone Sang (1991) and coney. Dominick Argento (b. 1927) The windmill blown down By the witch's fart, Jerry Rubino, Conductor And Saint George that O! broke the dragon's heart! A Toccata of Galuppi·s (1990) Dominick Argento (b. 1927) ·Street Cries· was premiered 25 years ago. The event took place about fifty yards behind Intermission you, in the aisles of the Guthrie Theater. The production was ·Shoemaker's Holiday,· music In the Land of Wu (1989) by Argento, words by Thomas Decker, who was Jackie T. Gabel (b. 1949) one of the first dramatists in Shakespeare's time to write about common folk. Argento set A.M.D.G. (Ad majorem Dei gloriam) (1939) -rnuch of the text to a kind of popular music, as Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) opposed to a more serious style, and he left a lot of the spoken dialogue in place, so the 1. Heaven-Haven result fits into a genre of opera known as 2. -

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014 Mark Adamo-- Little Women, Lysistrata John Adams—Nixon in China, Death of Klinghoffer, Doctor Atomic Dominick Argento—Postcard From Morocco, The Aspern Papers William Balcom—A View From the Bridge, McTeague Samuel Barber—Antony and Cleopatra, Vanessa Leonard Bernstein— A Quiet Place, Trouble in Tahiti Mark Blitzstein—Regina, Sacco and Venzetti, The Cradle Will Rock David Carlson—Anna Karenina Aaron Copland—The Tender Land John Corigliano—The Ghosts of Versailles Walter Damrosch—Cyrano, The Scarlet Letter Carlisle Floyd—Susannah, Of Mice and Men, Willie Stark, Cold Sassy Tree Lukas Foss—Introductions and Goodbyes George Gershwin—Porgy and Bess Philip Glass—Satyagraha, The Voyage, Einstein on the Beach, Akhnaten Ricky Ian Gordon—Grapes of Wrath Louis Gruenberg—The Emperor Jones Howard Hanson—Merry Mount John Harbison—The Great Gatsby, Winter’s Tale Jake Heggie—Moby Dick, Dead Man Walking Bernard Hermann—Wuthering Heights Jennifer Higdon—Cold Mountain (World Premiere, Santa Fe Opera, 2015) Scott Joplin—Treemonisha Gian Carlo Menotti—The Consul, The Telephone, Amahl and the Night Visitors Douglas Moore—Ballad of Baby Doe, The Devil and Daniel Webster, Carrie Nation Stephen Paulus—The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Woodlanders Tobias Picker—An American Tragedy, Emmeline, Therese Racquin Andre Previn—A Streetcar Named Desire Ned Rorem—Our Town Deems Taylor—Peter Ibbetson Terry Teachout—The Letter Virgil Thompson—Four Saints in Three Acts, The Mother of Us All Stewart Wallace—Harvey Milk Kurt Weill—Street Scene, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny . -

A Voice in Turmoil - Musical Settings of Catullus's Odi Et Amo: Opportunities Grasped and Missed

A Voice in Turmoil - Musical Settings of Catullus's Odi et Amo: Opportunities Grasped and Missed The briefest of Catullus's poems is perhaps his most famous, and yet it presents particular challenges to the composer who would put it to music. This paper documents four such attempts, made over four centuries, and discusses their various strengths and weaknesses. Such value judgments are based upon certain criteria, the chief of which assesses whether the composer is demonstrating sufficient comprehension and fluency with the language to complement the poet's message. However, there are other factors that contribute to a thorough evaluation of such a musical setting. Within the stylistic parameters of a given period, does the composer reflect, adapt or ignore Catullus's own musical elements, from overall rhythm to individual elements of sound, such as assonance and onomatopoeia? Is the best use made of the musical forces mustered to present the new version of the poem? Each attempt to set Catullus 85 is introduced with a short biographical note on the composer, followed by a recorded excerpt of the setting. These composers range from the 16th century Bohemian, Jakob Handl, to the German-Swiss, Carl Orff, who is followed by two contemporary composers - from the USA, Dominick Argento and from Latvia, Ugis Praulins. Following these sound samples, the paper poses a new question: how much do these modern artists owe to their ancient forbear? Would Catullus have objected to their use of his creation, or might he have reveled in their attention? -

Composer Brochure

CARTER lliott E composer_2006_01_04_cvr_v01.indd 2 4/30/2008 11:32:05 AM Elliott Carter Introduction English 1 Deutsch 4 Français 7 Abbreviations 10 Works Operas 12 Full Orchestra 13 Chamber Orchestra 18 Solo Instrument(s) and Orchestra 19 TABLE TABLE OF CONTENTS Ensemble and Chamber without Voice(s) 23 Ensemble and Chamber with Voice(s) 30 Piano(s) 32 Instrumental 34 Choral 39 Recordings 40 Chronological List of Works 46 Boosey & Hawkes Addresses 51 Cover photo: Meredith Heuer © 2000 Carter_2008_TOC.indd 3 4/30/2008 11:34:15 AM An introduction to the music of Carter by Jonathan Bernard Any composer whose career extends through eight decades—and still counting—has already demonstrated a remarkable staying power. But there are reasons far more compelling than mere longevity to regard Elliott Carter as the most eminent of living American composers, and as one of the foremost composers in the world at large. His name has come to be synonymous with music that is at once structurally formidable, expressively extraordinary, and virtuosically dazzling: music that asks much of listener and performer INTRODUCTION alike but gives far more in return. Carter was born in New York and, except during the later years of his education, has always lived there. After college and some postgraduate study at Harvard, like many an aspiring American composer of his generation who did not find the training he sought at home, Carter went off to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger, an experience which, while enabling a necessary development of technique, also lent his work a conservative, neoclassical style for a time.