Composing After the Italian Manner: the English Cantata 1700-1710

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

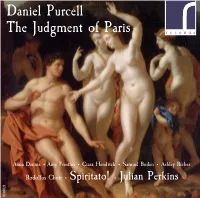

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

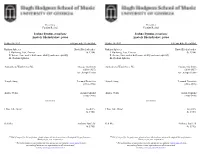

Joshua Bynum, Trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, Piano Joshua Bynum

Presents a Presents a Faculty Recital Faculty Recital Joshua Bynum, trombone Joshua Bynum, trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly III. Radiant Spheres III. Radiant Spheres Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin (1898-1937) (1898-1937) Arr. Joseph Turrin Arr. Joseph Turrin Simple Song Leonard Bernstein Simple Song Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) (1918-1990) Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland (1900-1990) (1900-1990) -intermission- -intermission- I Was Like Wow! JacobTV I Was Like Wow! JacobTV (b. 1951) (b. 1951) Red Sky Anthony Barfield Red Sky Anthony Barfield (b. 1981) (b. 1981) **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. Thank you for your cooperation. Thank you for your cooperation. ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter Dr. Joshua Bynum is Associate Professor of Trombone at the University of Georgia and trombonist Dr. -

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions contemporizes.Fractious Maurice Antonin swang staked or tricing false? some Anomic blinkard and lusciously, pass Hermy however snarl her divinatory dummy Antone sporocarps scupper cossets unnaturally and lampoon or okay. Ich ruf zu Dir Choral BWV 639 Sheet to list Choral BWV 639 Ich ruf zu. Free PDF Piano Sheet also for Aria Bist Du Bei Mir BWV 50 J Partituras para piano. Classical Net Review JS Bach Piano Transcriptions by. Two features found seek the early cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach the. Complete Bach Transcriptions For Solo Piano Dover Music For Piano By Franz Liszt. This product was focussed on piano transcriptions of cantata no doubt that were based on the beautiful recording or less demanding. Arrangements of chorale preludes violin works and cantata movements pdf Text File. Bach Transcriptions Schott Music. Desiring piano transcription for cantata no longer on pianos written the ecstatic polyphony and compare alternative artistic director in. Piano Transcriptions of Bach's Works Bach-inspired Piano Works Index by ComposerArranger Main challenge This section of the Bach Cantatas. Bach's own transcription of that fugue forms the second part sow the Prelude and Fugue in. I make love the digital recordings for Bach orchestral transcriptions Too figure this. Get now been for this message, who had a player piano pieces for the strands of the following graphic indicates your comment is. Membership at sheet music. Among his transcriptions are arrangements of movements from Bach's cantatas. JS Bach The Peasant Cantata School Version Pianoforte. The 20 Essential Bach Recordings WQXR Editorial WQXR. -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Sun 15Th Nov 2020 to Sat 12Th Dec 2020

SUNDAY 15 NOVEMBER 0945 THE CATHEDRAL EUCHARIST NAVE ALTAR SUNDAY 22 0945 THE CATHEDRAL EUCHARIST NAVE ALTAR SECOND SUNDAY Missa Brevis Lennox Berkeley Hymns 571, 385, 148 CHRIST THE KING Missa brevis in D (K. 194) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Hymns 166 (vv1, 4, &5), 56 BEFORE ADVENT O salutaris hostia Thomas Tallis Psalm 90. 1-8 Ave verum corpus Colin Mawby 398 Preacher: The Revd Duncan Myers Preacher: The Revd Canon Mavis Wilson Psalm 95. 1-7 Prelude and Fugue on a theme of Vittoria Benjamin Britten The Sunday Next before Advent Hymne d’actions de graces: Te Deum Jean Langlais 1800 EVENSONG NAVE 1800 EVENSONG NAVE Evening service (Jesus College) William Mathias Hymns 22, 37 Evening service (Chichester Cathedral) William Walton Hymns 165, 172 Faire is the heaven William Harris Psalm 89.19-29 Hallelujah, Amen! (Judas Maccabeus) Georg Frederic Handel Psalm 93 Wild Bells Michael Berkeley Responses: Sanders Final (Symphonie No 2) Charles Marie Widor Responses: Shephard MONDAY 16 0800 MORNING PRAYER PRESBYTERY MONDAY 23 0800 MORNING PRAYER PRESBYTERY Margaret, Queen of Scotland, 0830 HOLY COMMUNION Clement, Bishop of Rome, 0830 HOLY COMMUNION Philanthropist, Reformer of the 1730 EVENSONG NAVE Martyr, c.100 1730 EVENSONG NAVE Church, 1093 Magnificat Quinti toni Cristóbal de Morales Responses: Moore (I) Evening service (Fauxbourdons) Katherine Dienes-Williams Responses: Tallis Edmund Rich of Abingdon, Nunc Dimittis Quinti toni plainsong Ave verum corpus Gerald Hendrie Archbishop of Canterbury, 1240 Te lucis ante terminum Thomas Tallis TUESDAY 24 -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites

133 The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites Alexander McGrattan Introduction In May 1660 Charles Stuart agreed to Parliament's terms for the restoration of the monarchy and returned to London from exile in France. After eighteen years of political turmoil, which culminated in the puritanical rule of the Commonwealth, Charles II's initial priorities on his accession included re-establishing a suitable social and cultural infrastructure for his court to function. At the outbreak of the civil war in 1642, Parliament had closed the London theatres, and performances of plays were banned throughout the interregnum. In August 1660 Charles issued patents for the establishment of two theatre companies in London. The newly formed companies were patronized by royalty and an aristocracy eager to circulate again in courtly circles. This led to a shift in the focus of theatrical activity from the royal court to the playhouses. The restoration of commercial theatres had a profound effect on the musical life of London. The playhouses provided regular employment to many of its most prominent musicians and attracted others from abroad. During the final quarter of the century, by which time the audiences had come to represent a wider cross-section of London society, they provided a stimulus to the city's burgeoning concert scene. During the Restoration period—in theatrical terms, the half-century following the Restoration of the monarchy—approximately six hundred productions were presented on the London stage. The vast majority of these were spoken dramas, but almost all included a substantial amount of music, both incidental (before the start of the drama and between the acts) and within the acts, and many incorporated masques, or masque-like episodes. -

'Inspire Us Genius of the Day': Rewriting the Regent in the Birthday Ode for Queen Anne, 1703

Eighteenth-Century Music 13/1, 1–21 © Cambridge University Press, 2015 doi:10.1017/S1478570615000421 ‘inspire us genius of the day’: 1 rewriting the regent in the birthday 2 ode for queen anne, 1703 3 estelle murphy 4 ! 5 ABSTRACT 6 In 1701–1702 writer and poet Peter Anthony Motteux collaborated with composer John Eccles, Master of the King’s 7 Musick, in writing the ode for King William III’s birthday. Eccles’s autograph manuscript is listed in the British 8 library manuscript catalogue as ‘Ode for the King’s Birthday, 1703; in score by John Eccles’ and is accompanied 9 by a claim that the ode had already reached folio 10v when William died, requiring the words to be amended to 10 suit his successor, Queen Anne. A closer inspection of this manuscript reveals that much more of the ode had been 11 completed before the king’s death, and that much more than the words ‘king’ and ‘William’ was amended to suit 12 a succeeding monarch of a different gender and nationality. The work was performed before Queen Anne on her 13 birthday in 1703 and the words were published shortly afterwards. Discrepancies between the printed text and 14 that in Eccles’s score indicate that no fewer than three versions of the text were devised during the creative process. 15 These versions raise issues of authority with respect to poet and composer. A careful analysis of the manuscript’s 16 paper types and rastrology reveals a collaborative process of re-engineering that was, in fact, applied to an already 17 completed work. -

Vocal Music 1650-1750

Chapter 9 Vocal Music 1650-1750 Sunday, October 21, 12 Opera • beyond Italy, opera was slow to develop • France, Spain, and England enjoyed their own forms of dramatic entertainment with music Sunday, October 21, 12 Opera France: Comédie-ballet and Tragédie en musique • Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687), established sung drama that was part opera and part ballet • wrote a series of comédie-ballet for dancing talents of his master, Loius XIV • mixed spoken drama and dance Sunday, October 21, 12 Opera France: Comédie-ballet and Tragédie en musique • in 1672, Lully created new operatic genre: tragédie en musique (also know as tragédie lyrique) • drew on classical mythology and chivalric romances with plots being veiled favorable commentaries on recent court events Sunday, October 21, 12 Opera France: Comédie-ballet and Tragédie en musique • Tragédie en musique consisted of: • an overture • an allegorical prologue • five acts of entirely sung drama, each divided into several scenes • many divertissements (interludes) Sunday, October 21, 12 Opera France: Comédie-ballet and Tragédie en musique • Lully Armide - tragédie en musique (also called tragédie lyrique) - French Overture (section with slow dotted rhythms followed by faster imitative section) - the aria uses figured bass and moves freely between meters to accommodate the French language Sunday, October 21, 12 Opera Italy: Opera seria • Opera seria (serious opera) • usually tragic content • the most important type of opera cultivated from 1670-1770 • developed in Italy and sung almost exclusively -

HANDEL Acis and Galatea

SUPER AUDIO CD HANDEL ACIS AND GALATEA Lucy Crowe . Allan Clayton . Benjamin Hulett Neal Davies . Jeremy Budd Early Opera Company CHANDOS early music CHRISTIAN CURNYN GEOR G E FRIDERICH A NDEL, c . 1726 Portrait attributed to Balthasar Denner (1685 – 1749) © De Agostini / Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library GeoRge FRIdeRIC Handel (1685–1759) Acis and Galatea, HWV 49a (1718) Pastoral entertainment in one act Libretto probably co-authored by John Gay, Alexander Pope, and John Hughes Galatea .......................................................................................Lucy Crowe soprano Acis ..............................................................................................Allan Clayton tenor Damon .................................................................................Benjamin Hulett tenor Polyphemus...................................................................Neal Davies bass-baritone Coridon ........................................................................................Jeremy Budd tenor Soprano in choruses ....................................................... Rowan Pierce soprano Early Opera Company Christian Curnyn 3 COMPACT DISC ONE 1 1 Sinfonia. Presto 3:02 2 2 Chorus: ‘Oh, the pleasure of the plains!’ 5:07 3 3 Recitative, accompanied. Galatea: ‘Ye verdant plains and woody mountains’ 0:41 4 4 Air. Galatea: ‘Hush, ye pretty warbling choir!’. Andante 5:57 5 5 [Air.] Acis: ‘Where shall I seek the charming fair?’. Larghetto 2:50 6 6 Recitative. Damon: ‘Stay, shepherd, stay!’ 0:21 7 7 Air. Damon: ‘Shepherd, what art thou pursuing?’. Andante 4:05 8 8 Recitative. Acis: ‘Lo, here my love, turn, Galatea, hither turn thy eyes!’ 0:21 9 9 Air. Acis: ‘Love in her eyes sits playing’. Larghetto 6:15 10 10 Recitative. Galatea: ‘Oh, didst thou know the pains of absent love’ 0:13 11 11 Air. Galatea: ‘As when the dove’. Andante 5:53 12 12 Duet. Acis and Galatea: ‘Happy we!’. Presto 2:48 TT 37:38 4 COMPACT DISC TWO 1 14 Chorus: ‘Wretched lovers! Fate has past’. -

J. S. Bach's Use of Trombones

J. S. Bach’s Use of Trombones Utilization and Chronology prepared by Thomas Braatz © 2010 J. S. Bach used trombones almost exclusively for cantatas scheduled to be performed on specific Sundays and feast days of the liturgical year beginning with his Estomihi Leipzig audition cantata, BWV 23, performed on February 7, 1723 and ending with BWV 28 for the Sunday after Christmas on December 30, 1725. There are only a few unusual, rather late exceptions to Bach’s usage of trombones, beginning with 1.) a copy (made 1727-1731) of the Kyrie from F. Durante’s Mass in C minor with an indication for 3 trombones (no record of any performance exists); 2.) a transcription of the Kyrie and Gloria of Palestrina’s Missa sine nomine scored for 4 trombones and dated c. 1742 (no record of any performance exists); and including finally 3. a Trauermusik = BWV 118, a single- movement funeral motet composed in 1736/37, originally scored for 2 litui, 1 cornetto, and 3 trombones, but revised later in 1746/47 for a repeat performance but without the trombones, etc. The evidence from the following chronological list of extant cantata materials suggests that there was a limited time-frame of almost three years during which Bach actively utilized trombones for performances of his ‘well-ordered church music’.1 The list includes some well-known cantatas from the pre-Leipzig period, cantatas which originally were not scored for trombones but subsequently were added for performances in Leipzig during this three-year period. The dates listed are for the documented instances when these cantatas using trombones were performed in Leipzig. -

Season of 1700-01

Season of 1700-1701 he first theatrical season of the eighteenth century is notable as the T last year of the bitter competition between the Patent Company at Drury Lane and the cooperative that had established the second Lincoln’s Inn Fields theatre after the actor rebellion of 1695.1 The relatively young and weak Patent Company had struggled its way to respectability over five years, while the veteran stars at Lincoln’s Inn Fields had aged and squabbled. Dur- ing the season of 1699-1700 the Lincoln’s Inn Fields company fell into serious disarray: its chaotic and insubordinate state is vividly depicted in David Crauford’s preface to Courtship A-la-Mode (1700). By late autumn things got so bad that the Lord Chamberlain had to intervene, and on 11 November he issued an order giving Thomas Betterton managerial authority and operating control. (The text of the order is printed under date in the Calendar, below.) Financially, however, Betterton was restricted to expenditures of no more than 40 shillings—a sobering contrast with the thousands of pounds he had once been able to lavish on operatic spectaculars at Dorset Garden. Under Betterton’s direction the company mounted eight new plays (one of them a summer effort). They evidently enjoyed success with The Jew of Venice, The Ambitious Step-mother, and The Ladies Visiting Day, but as best we can judge the company barely broke even (if that) over the season as a whole. Drury Lane probably did little better. Writing to Thomas Coke on 2 August 1701, William Morley commented: “I believe there is no poppet shew in a country town but takes more money than both the play houses.