Season of 1700-01

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shearer West Phd Thesis Vol 1

THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON (VOL. I) Shearer West A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 1986 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2982 This item is protected by original copyright THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON Ph.D. Thesis St. Andrews University Shearer West VOLUME 1 TEXT In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the I work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. ABSTRACT A theatrical portrait is an image of an actor or actors in character. This genre was widespread in eighteenth century London and was practised by a large number of painters and engravers of all levels of ability. The sources of the genre lay in a number of diverse styles of art, including the court portraits of Lely and Kneller and the fetes galantes of Watteau and Mercier. Three types of media for theatrical portraits were particularly prevalent in London, between ca745 and 1800 : painting, print and book illustration. -

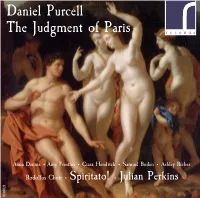

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

Sun 15Th Nov 2020 to Sat 12Th Dec 2020

SUNDAY 15 NOVEMBER 0945 THE CATHEDRAL EUCHARIST NAVE ALTAR SUNDAY 22 0945 THE CATHEDRAL EUCHARIST NAVE ALTAR SECOND SUNDAY Missa Brevis Lennox Berkeley Hymns 571, 385, 148 CHRIST THE KING Missa brevis in D (K. 194) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Hymns 166 (vv1, 4, &5), 56 BEFORE ADVENT O salutaris hostia Thomas Tallis Psalm 90. 1-8 Ave verum corpus Colin Mawby 398 Preacher: The Revd Duncan Myers Preacher: The Revd Canon Mavis Wilson Psalm 95. 1-7 Prelude and Fugue on a theme of Vittoria Benjamin Britten The Sunday Next before Advent Hymne d’actions de graces: Te Deum Jean Langlais 1800 EVENSONG NAVE 1800 EVENSONG NAVE Evening service (Jesus College) William Mathias Hymns 22, 37 Evening service (Chichester Cathedral) William Walton Hymns 165, 172 Faire is the heaven William Harris Psalm 89.19-29 Hallelujah, Amen! (Judas Maccabeus) Georg Frederic Handel Psalm 93 Wild Bells Michael Berkeley Responses: Sanders Final (Symphonie No 2) Charles Marie Widor Responses: Shephard MONDAY 16 0800 MORNING PRAYER PRESBYTERY MONDAY 23 0800 MORNING PRAYER PRESBYTERY Margaret, Queen of Scotland, 0830 HOLY COMMUNION Clement, Bishop of Rome, 0830 HOLY COMMUNION Philanthropist, Reformer of the 1730 EVENSONG NAVE Martyr, c.100 1730 EVENSONG NAVE Church, 1093 Magnificat Quinti toni Cristóbal de Morales Responses: Moore (I) Evening service (Fauxbourdons) Katherine Dienes-Williams Responses: Tallis Edmund Rich of Abingdon, Nunc Dimittis Quinti toni plainsong Ave verum corpus Gerald Hendrie Archbishop of Canterbury, 1240 Te lucis ante terminum Thomas Tallis TUESDAY 24 -

Season of 1703-04 (Including the Summer Season of 1704), the Drury Lane Company Mounted 64 Mainpieces and One Medley on a Total of 177 Nights

Season of 1703-1704 n the surface, this was a very quiet season. Tugging and hauling occur- O red behind the scenes, but the two companies coexisted quite politely for most of the year until a sour prologue exchange occurred in July. Our records for Drury Lane are virtually complete. They are much less so for Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which advertised almost not at all until 18 January 1704. At that time someone clearly made a decision to emulate Drury Lane’s policy of ad- vertising in London’s one daily paper. Neither this season nor the next did the LIF/Queen’s company advertise every day, but the ads become regular enough that we start to get a reasonable idea of their repertory. Both com- panies apparently permitted a lot of actor benefits during the autumn—pro- bably a sign of scanty receipts and short-paid salaries. Throughout the season advertisements make plain that both companies relied heavily on entr’acte song and dance to pull in an audience. Newspaper bills almost always mention singing and dancing, sometimes specifying the items in considerable detail, whereas casts are never advertised. Occasionally one or two performers will be featured, but at this date the cast seems not to have been conceived as the basic draw. Or perhaps the managers were merely economizing, treating newspaper advertisements as the equivalent of handbills rather than “Great Bills.” The importance of music to the public at this time is also evident in the numerous concerts of various sorts on offer, and in the founding of The Monthly Mask of Vocal Musick, a periodical devoted to printing new songs, including some from the theatre.1 One of the most interesting developments of this season is a ten-concert series generally advertised as “The Subscription Musick.” So far as we are aware, it has attracted no scholarly commentary whatever, but it may well be the first series of its kind in the history of music in London. -

An A2 Timeline of the London Stage Between 1660 and 1737

1660-61 1659-60 1661-62 1662-63 1663-64 1664-65 1665-66 1666-67 William Beeston The United Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company @ Salisbury Court Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company & Thomas Killigrew @ Salisbury Court @Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Rhodes’s Company @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Red Bull Theatre @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields George Jolly John Rhodes @ Salisbury Court @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane The King’s Company The King’s Company PLAGUE The King’s Company The King’s Company The King’s Company Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew June 1665-October 1666 Anthony Turner Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew @ Vere Street Theatre @ Vere Street Theatre & Edward Shatterell @ Red Bull Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Bridges Street Theatre, GREAT FIRE @ Red Bull Theatre Drury Lane (from 7/5/1663) The Red Bull Players The Nursery @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane September 1666 @ Red Bull Theatre George Jolly @ Hatton Garden 1676-77 1675-76 1674-75 1673-74 1672-73 1671-72 1670-71 1669-70 1668-69 1667-68 The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company Thomas Betterton & William Henry Harrison and Thomas Henry Harrison & Thomas Sir William Davenant Smith for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields -

Jane Milling

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘“For Without Vanity I’m Better Known”: Restoration Actors and Metatheatre on the London Stage.’ AUTHORS Milling, Jane JOURNAL Theatre Survey DEPOSITED IN ORE 18 March 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/4491 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Theatre Survey 52:1 (May 2011) # American Society for Theatre Research 2011 doi:10.1017/S0040557411000068 Jane Milling “FOR WITHOUT VANITY,I’M BETTER KNOWN”: RESTORATION ACTORS AND METATHEATRE ON THE LONDON STAGE Prologue, To the Duke of Lerma, Spoken by Mrs. Ellen[Nell], and Mrs. Nepp. NEPP: How, Mrs. Ellen, not dress’d yet, and all the Play ready to begin? EL[LEN]: Not so near ready to begin as you think for. NEPP: Why, what’s the matter? ELLEN: The Poet, and the Company are wrangling within. NEPP: About what? ELLEN: A prologue. NEPP: Why, Is’t an ill one? NELL[ELLEN]: Two to one, but it had been so if he had writ any; but the Conscious Poet with much modesty, and very Civilly and Sillily—has writ none.... NEPP: What shall we do then? ’Slife let’s be bold, And speak a Prologue— NELL[ELLEN]: —No, no let us Scold.1 When Samuel Pepys heard Nell Gwyn2 and Elizabeth Knipp3 deliver the prologue to Robert Howard’s The Duke of Lerma, he recorded the experience in his diary: “Knepp and Nell spoke the prologue most excellently, especially Knepp, who spoke beyond any creature I ever heard.”4 By 20 February 1668, when Pepys noted his thoughts, he had known Knipp personally for two years, much to the chagrin of his wife. -

First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide the Beaux’ Stratagem

First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide The Beaux’ Stratagem by George Farquhar adapted by Thornton Wilder and Ken Ludwig directed by Michael Kahn November 7— December 31, 2006 First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide Table of Contents Page Number Welcome to the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s productionproduction of An EnemyofThe ofBeaux’ the PeopleStratagemby Henrikby George Ibsen! Farquhar, adapted by A Brief History of the Audience……………………..1 Thornton Wilder and Ken Ludwig! Each season, the Shakespeare Theatre Company Eachpresents season, five theplays Shakespeare by William Theatre Shakespeare Company and About the Playwright otherpresents classicfive plays playwrights. by William ShakespeareThe goal andof all Farquhar’s Biography………………………………….…3 Educationother classic Department playwrights. Programs The is to goaldeepen of all Biographies of the Adapters…... ……………………4 Educationunderstanding, Department appreciation Programs and connectionis to deepen to The End of an Era—Restoration Comedy……..5 understanding,classic theatre appreciationin learners and ofconnection all ages. to One On the Adaptation………………………………………….8 approachclassic theatre is thein publicationlearners ofFirst of all Folio:ages. One Writing and Rewriting—The Road to approachTeacher Curriculum is the publication Guides. ofFirst Folio: Teacher Adaptation……………………………………………………..10 Curriculum Guides. For the 2006•07 season, the Education DepartmentFor the 2006•07will publish season,First Folio:the TeacherEducation About the Play CurriculumDepartment Guides willfor publishour Firstproductions -

Print This Article

JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES – VOLUME 17 (2019), 127-147. http://doi.org/10.18172/jes.3565 “DWINDLING DOWN TO FARCE”?: APHRA BEHN’S APPROACH TO FARCE IN THE LATE 1670S AND 80S JORGE FIGUEROA DORREGO1 Universidade de Vigo [email protected] ABSTRACT. In spite of her criticism against farce in the paratexts of The Emperor of the Moon (1687), Aphra Behn makes an extensive use of farcical elements not only in that play and The False Count (1681), which are actually described as farces in their title pages, but also in Sir Patient Fancy (1678), The Feign’d Curtizans (1679), and The Second Part of The Rover (1681). This article contends that Behn adapts French farce and Italian commedia dell’arte to the English Restoration stage mostly resorting to deception farce in order to trick old husbands or fathers, or else foolish, hypocritical coxcombs, and displaying an impressive, skilful use of disguise and impersonation. Behn also turns widely to physical comedy, which is described in detail in stage directions. She appropriates farce in an attempt to please the audience, but also in the service of her own interests as a Tory woman writer. Keywords: Aphra Behn, farce, commedia dell’arte, Restoration England, deception, physical comedy. 1 The author wishes to acknowledge funding for his research from the Spanish government (MINECO project ref. FFI2015-68376-P), the Junta de Andalucía (project ref. P11-HUM-7761) and the Xunta de Galicia (Rede de Lingua e Literatura Inglesa e Identidade III, ref. ED431D2017/17). 127 Journal of English Studies, vol. 17 (2019) 127-147 Jorge Figueroa DORREGO “DWINDLING DOWN TO FARCE”?: LA APROXIMACIÓN DE APHRA BEHN A LA FARSA EN LAS DÉCADAS DE 1670 Y 1680 RESUMEN. -

The Whore and the Breeches Role As Articulators of Sexual Economic Theory in the Intrigue Plays of Aphra Behn

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 Masked Criticism: the Whore and the Breeches Role as Articulators of Sexual Economic Theory in the Intrigue Plays of Aphra Behn. Mary Katherine Politz Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Politz, Mary Katherine, "Masked Criticism: the Whore and the Breeches Role as Articulators of Sexual Economic Theory in the Intrigue Plays of Aphra Behn." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7163. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7163 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor qualify illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. if Also,unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

BARSTOW, Robert Squire, 1936- the THEATRE MUSIC of DANIEL PURCELL

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 6 9 -4 8 4 2 BARSTOW, Robert Squire, 1936- THE THEATRE MUSIC OF DANIEL PURCELL. (VOLUMES I AND II). The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1968 Music University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Robert Squire Barstow 1969 - THE THEATRE MUSIC OF DANIEL PURCELL .DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for_ the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert Squire Barstow, B.M., M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1968 Approved by Department of Music ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To the Graduate School of the Ohio State University and to the Center of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, whose generous grants made possible the procuring of materials necessary for this study, the author expresses his sincere thanks. Acknowledgment and thanks are also given to Dr. Keith Mixter and to Dr. Mark Walker for their timely criticisms in the final stages of this paper. It is to my adviser Dr. Norman Phelps, however, that I am most deeply indebted. I shall always be grateful for his discerning guidance and for the countless hours he gave to my problems. Words cannot adequately express the profound gratitude I owe to Dr. C. Thomas Barr and to my wife. Robert S. Barstow July 1968 1 1 VITA September 5, 1936 Born - Gt. Bend, Kansas 1958 .......... B.M. , ’Port Hays Kansas State College, Hays, Kansas 1958-1961 .... Instructor, Goodland Public Schools, Goodland, Kansas 1961-1964 .... National Defense Graduate Fellow, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1963............ M.A., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio __ 1964-1966 ... -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS DURING THE STRUGGLE FOR CONTROL OF THE LONDON THEATRE, 1695-1710 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Jay Edw ard Oney, B.A., M.A. -

Melanie Bigold, ' “The Theatre of the Book”: Marginalia and Mise En

occasional publications no.1 ‘Theatre of the Book’ Marginalia and Mise en Page in the Cardiff Rare Books Restoration Drama Collection Melanie Bigold Centre for Editorial and Intertextual Research, Cardiff University ‘ “Theatre of the Book”: Marginalia and Mise en Page in the Cardiff Rare Books Restoration Drama Collection’ (CEIR Occasional Publications No. 1). Available online <http://cardiffbookhistory.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/bigold.pdf>. © 2013 Melanie Bigold; (editor: Anthony Mandal). The moral rights of the author have been asserted. Originally published in December 2013, by the Centre for Editorial and Intertextual Research, Cardiff University. Typeset in Adobe Minion Pro 11 / 13, at the Centre for Editorial and Intertextual Research, using Adobe InDesign cc; final output rendered with Adobe Acrobat xi Professional. Summary he value-added aspect of both marginalia and provenance has long Tbeen recognized. Ownership marks and autograph annotations from well-known writers or public figures increase the intellectual interest as well as monetary value of a given book. Handwritten keys, pointers, and marginal glosses can help to reveal unique, historical information unavaila- ble in the printed text; information that, in turn, can be used to reconstruct various reading and interpretive experiences of the past. However, increas- ingly scholars such as Alan Westphall have acknowledged that the ‘study of marginalia and annotations’ results in ‘microhistory, producing narratives that are often idiosyncratic’. While twenty to fifty percent of early modern texts have some sort of marking in them, many of these forays in textual alterity are unsystematic and fail to address, as William Sherman notes, ‘the larger patterns that most literary and historical scholars have as their goal’.