Using Baroque Vocal Music to Introduce Horn Students to the Musical Concepts of Expression, Articulation, Phrasing, and Tempo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

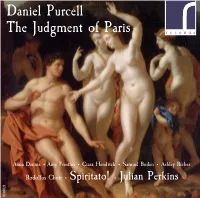

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

Sun 15Th Nov 2020 to Sat 12Th Dec 2020

SUNDAY 15 NOVEMBER 0945 THE CATHEDRAL EUCHARIST NAVE ALTAR SUNDAY 22 0945 THE CATHEDRAL EUCHARIST NAVE ALTAR SECOND SUNDAY Missa Brevis Lennox Berkeley Hymns 571, 385, 148 CHRIST THE KING Missa brevis in D (K. 194) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Hymns 166 (vv1, 4, &5), 56 BEFORE ADVENT O salutaris hostia Thomas Tallis Psalm 90. 1-8 Ave verum corpus Colin Mawby 398 Preacher: The Revd Duncan Myers Preacher: The Revd Canon Mavis Wilson Psalm 95. 1-7 Prelude and Fugue on a theme of Vittoria Benjamin Britten The Sunday Next before Advent Hymne d’actions de graces: Te Deum Jean Langlais 1800 EVENSONG NAVE 1800 EVENSONG NAVE Evening service (Jesus College) William Mathias Hymns 22, 37 Evening service (Chichester Cathedral) William Walton Hymns 165, 172 Faire is the heaven William Harris Psalm 89.19-29 Hallelujah, Amen! (Judas Maccabeus) Georg Frederic Handel Psalm 93 Wild Bells Michael Berkeley Responses: Sanders Final (Symphonie No 2) Charles Marie Widor Responses: Shephard MONDAY 16 0800 MORNING PRAYER PRESBYTERY MONDAY 23 0800 MORNING PRAYER PRESBYTERY Margaret, Queen of Scotland, 0830 HOLY COMMUNION Clement, Bishop of Rome, 0830 HOLY COMMUNION Philanthropist, Reformer of the 1730 EVENSONG NAVE Martyr, c.100 1730 EVENSONG NAVE Church, 1093 Magnificat Quinti toni Cristóbal de Morales Responses: Moore (I) Evening service (Fauxbourdons) Katherine Dienes-Williams Responses: Tallis Edmund Rich of Abingdon, Nunc Dimittis Quinti toni plainsong Ave verum corpus Gerald Hendrie Archbishop of Canterbury, 1240 Te lucis ante terminum Thomas Tallis TUESDAY 24 -

Season of 1700-01

Season of 1700-1701 he first theatrical season of the eighteenth century is notable as the T last year of the bitter competition between the Patent Company at Drury Lane and the cooperative that had established the second Lincoln’s Inn Fields theatre after the actor rebellion of 1695.1 The relatively young and weak Patent Company had struggled its way to respectability over five years, while the veteran stars at Lincoln’s Inn Fields had aged and squabbled. Dur- ing the season of 1699-1700 the Lincoln’s Inn Fields company fell into serious disarray: its chaotic and insubordinate state is vividly depicted in David Crauford’s preface to Courtship A-la-Mode (1700). By late autumn things got so bad that the Lord Chamberlain had to intervene, and on 11 November he issued an order giving Thomas Betterton managerial authority and operating control. (The text of the order is printed under date in the Calendar, below.) Financially, however, Betterton was restricted to expenditures of no more than 40 shillings—a sobering contrast with the thousands of pounds he had once been able to lavish on operatic spectaculars at Dorset Garden. Under Betterton’s direction the company mounted eight new plays (one of them a summer effort). They evidently enjoyed success with The Jew of Venice, The Ambitious Step-mother, and The Ladies Visiting Day, but as best we can judge the company barely broke even (if that) over the season as a whole. Drury Lane probably did little better. Writing to Thomas Coke on 2 August 1701, William Morley commented: “I believe there is no poppet shew in a country town but takes more money than both the play houses. -

BARSTOW, Robert Squire, 1936- the THEATRE MUSIC of DANIEL PURCELL

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 6 9 -4 8 4 2 BARSTOW, Robert Squire, 1936- THE THEATRE MUSIC OF DANIEL PURCELL. (VOLUMES I AND II). The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1968 Music University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Robert Squire Barstow 1969 - THE THEATRE MUSIC OF DANIEL PURCELL .DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for_ the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert Squire Barstow, B.M., M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1968 Approved by Department of Music ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To the Graduate School of the Ohio State University and to the Center of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, whose generous grants made possible the procuring of materials necessary for this study, the author expresses his sincere thanks. Acknowledgment and thanks are also given to Dr. Keith Mixter and to Dr. Mark Walker for their timely criticisms in the final stages of this paper. It is to my adviser Dr. Norman Phelps, however, that I am most deeply indebted. I shall always be grateful for his discerning guidance and for the countless hours he gave to my problems. Words cannot adequately express the profound gratitude I owe to Dr. C. Thomas Barr and to my wife. Robert S. Barstow July 1968 1 1 VITA September 5, 1936 Born - Gt. Bend, Kansas 1958 .......... B.M. , ’Port Hays Kansas State College, Hays, Kansas 1958-1961 .... Instructor, Goodland Public Schools, Goodland, Kansas 1961-1964 .... National Defense Graduate Fellow, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1963............ M.A., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio __ 1964-1966 ... -

Universiv Micrwilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy o f a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1 The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image o f the page can be found in the adjacent frame. I f copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

PURCELL COLLECTION Opera, Albion and Albanius, Which Was Set to Music EXTENSIVE LINER NOTES by the Spanish Composer Luis Grabu and Performed in 1685

PURCELL COLLECTION opera, Albion and Albanius, which was set to music EXTENSIVE LINER NOTES by the Spanish composer Luis Grabu and performed in 1685. Six years later, after the Glorious Revolution had stripped Dryden of the CD1+2 Laureateship, and poverty had forced him once ‘King Arthur’: Purcell’s Music and Dryden’s Play again to write for the public stage, he dusted off John Dryden called King Arthur ‘A dramatick the old play, altered its original political message, opera’, a proud and idiosyncratic subtitle which and sent it to Purcell, whose music he had come to has caused much confusion. It has been said admire, especially the brilliantly successful semi‐ unfairly that this work is neither dramatic nor an opera Dioclesian (1690). opera. To be sure it is not like a real opera, nor could it be easily turned into one. King Arthur is How much revision the play required is unknown, very much a play, a tragi‐comedy which happens to since the original version does not survive, but include some exceptionally fine music. During the Dryden implies major surgery: ‘… not to offend the Restoration, the term ‘opera’ was used to describe present Times, nor a Government which has any stage work with elaborate scenic effects, and hitherto protected me, I have been oblig’d…to did not necessarily mean an all‐sung music drama. alter the first Design, and take away so many The original 1691 production of King Arthur, Beauties from the Writing’. Besides trimming for though it included flying chariots and trap‐door political reasons, he also had to satisfy his new effects, was modest compared to other similar collaborator: ‘the Numbers of Poetry and Vocal works. -

Presents March 14, 2021 Doug Oldham Recital Hall MUSIC

presents March 14, 2021 Doug Oldham Recital Hall MUSIC 170 5:30 PM Strike the Viol Henry Purcell (1659-1695) Music for a while Henry Purcell (1659-1695) ~~~~~~ Pieta, Signore! Allessandro Stradella (1645-1682) O del mio dolce ardor Christoph Willibald von Gluck (1714-1787) Voi che sapete Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart from Le nozze di Figaro (1756-1791) ~~~~~~ An die Musik Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Lachen und Weinen Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Lied der Mignon Franz Schubert (1797-1828) ~~~~~~ Chanson d’amour Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Beau soir Claude Debussy (1862-1918) ~~~~~~ My God is So High Spiritual arr. Hall Johnson City Called Heaven Spiritual arr. Hall Johnson Strike the Viol Strike the Viol is the fifth movement of “Come ye Sons of Art” or “Ode for Queen Mary’s Birthday”, a composition written in 1694 by Henry Purcell; one of a series of odes written to honor the birthday of Queen Mary II of England. It was originally written for male alto or counter tenor, but the voice part was raised an octave in relation to the bass. The entire song was then transposed to suit our modern-day voices. The ode was originally scored for 2 recorders, 2 oboes, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings, basso continuo, and a choir with soloists on each voice part. This “striking” song is a call or command to sing and play instruments! Music for a While This text is derive from John Dryden’s play Oedipus: A Tragedy written in 1678. In 1692, Purcell set parts of it to music. The words are taken from Greek mythology and talks about the power of music. -

Composing After the Italian Manner: the English Cantata 1700-1710

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Faculty Publications Music 2014 Composing after the Italian Manner: The nE glish Cantata 1700-1710 Jennifer Cable University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/music-faculty-publications Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Cable, Jennifer. "Composing after the Italian Manner: The nE glish Cantata 1700-1710." In The Lively Arts of the London Stage: 1675-1725, edited by Kathryn Lowerre, 63-83. Farnham: Ashgate, 2014. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 4 Composing after the Italian Manner: The English Cantata 1700-1710 Jennifer Cable Charles Gildon, in addressing the state of the arts in his 1710 publication The Life of Mr. Thomas Betterton, the Late Eminent Tragedian, offered the following observation concerning contemporary music and, in particular, the music of Henry Purcell: Music, as well as Verse, is subject to that Rule of Horace; He that would have Spectators share his Grief, Must write not only well, but movingly. 1 According to Gildon, the best judges of music were the 'Masters ofComposition', and he called on them to be the arbiters of whether the taste in music had been improved since Purcell's day.2 However, Gildon's English 'masters of composition' were otherwise occupied, as they were just beginning to come to terms with what was surely a concerning, if not outright frustrating, situation. -

Henry Purcell's

Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas VANCOUVER EARLY MUSIC FESTIVAL 2015 the ensemble programme notes | purcell's "dido and aeneas" Alexander Weimann The God-like Man, music director & harpsichord Alas, too soon retir’d, Monica Whicher As He too late began. soprano We beg not Hell, our Orpheus to restore, Pascale Beaudin Had He been there, soprano Their Sovereign’s fear Jacqueline Woodley Had sent Him back before. soprano The pow’r of Harmony too well they know, Catherine Webster He long e’er this had Tun’d their jarring Spheres, soprano And left no Hell below. Danielle Reuter-Harrah From the “Ode on the Death of Henry Purcell" mezzo-soprano – John Dryden” Josée Lalonde alto Henry Purcell, the “English Orpheus”, was born in London in 1659 into a family of musicians. Reginald L. Mobley Both his father and uncle were members of the Chapel Royal and sang for the coronation alto ceremonies of Charles II. Precocious young Henry, too, sang in the choir until his voice broke, at Charles Daniels which point he was appointed assistant keeper of the King’s keyboards and wind instruments. tenor Over a very short time, his superior abilities as an organist, violinist and composer earned Bernard Cayouette tenor him the profound respect of peers and teachers alike. This led him to secure one of the most illustrious musical posts in England – organist of Westminster Abbey. Purcell’s teacher, Dr. Jean-Sébastien Allaire tenor John Blow went so far as to give up this position, when it became clear that the student had Sumner Thompson surpassed his master. -

Jeremiah Clarke: Concerted Works for Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra

Jeremiah Clarke: Concerted Works for Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra PETER HOLMAN In addition to the abbreviations used in Oxford Music Online, gbv = great bass viol 1: Song on the Assumption, ‘Hark, she’s called, the parting hour is come’ (Richard Crashaw), T202 Sources GB-Ob, MS Tenbury 1226, ff. 102-124v (autograph); GB-Ob, MS Tenbury 1175, pp. 166-91 (Thomas Barrow, copied from Tenbury 1226) Scoring Tr, Tr, Ct, T, B solo, SCtTB tutti, 2 rec, [2 ob], 4 vn, 4 vla, 3 b (2 gbv), bc Performance ?15 August 1695 (Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary), Great Hall, Longleat House 2: Song on the Death of the Famous Mr Henry Purcell, ‘Come along for a dance and a song’ (Anonymous), T200 Sources GB-Lbl, Add. MS 30934, ff. 3-34v (London A); GB-Lbl, Add. MS 31812, ff. 3-31 (R.J.S. Stevens, 1828, copied from a lost early source) Scoring Tr (Jemmy Bowen), S (Laetitia Cross), Ct (John Freeman), B (Richard Leveridge), SCtTB tutti, 2 tpt, timp, 2 rec, 2 ob, [?ten ob], 2 vn, vla, b (gbv), bc (hpscd) Performance ?January 1696, Drury Lane (staged performance) Edition Odes on the Death of Henry Purcell, ed. Alan Howard, Purcell Society Companion Series, 5 (London, 2013), pp. 25-75. 3: [Song] on his Majesty’s Happy Deliverance, ‘Now Albion, raise thy drooping head’ (Anonymous), T205 Source GB-Ob, MS Tenbury 1232, ff. 48-61v (London A) Scoring S, Ct, B solo, SCtTB tutti, 2 tpt, 2 rec, 2 ob, 2 vn (solo/tutti), vla, b, bc Performance ?16 April 1696, ?Drury Lane (Thanksgiving Day for the exposure of the Assassination Plot) 4: The World in the Moon (Elkanah Settle): Prologue, ‘Welcome Beauty, all the charms’ T301A; Entertainment after Act I, ‘Within this happy world above’, T301B Source GB-Lbl, Add. -

Handel Coronation

Australian Brandenburg Orchestra HANDEL CORONATION Paul Dyer Artistic Director and conductor Brandenburg Choir (Sydney) The Choir of Trinity College (University of Melbourne) & Melbourne Grammar School Chapel Choir PRogRam Purcell Suite from Abdelazer Purcell Birthday Ode to Queen Mary Come Ye Sons of Art INTERVAL Handel Concerto a due cori No. 2, HWV 333 Handel Coronation Anthem No. 1 Zadok the Priest HWV 258 Handel Coronation Anthem No. 3 The King Shall Rejoice HWV 260 The concert will last approximately two hours including interval. SYDNEY City Recital Hall Angel Place Friday 30, Saturday 31 July, Wednesday 4, Friday 6, Saturday 7 August 2010 all at 7 pm Saturday 7 August 2010 at 2 pm MELBOURNE Melbourne Recital Centre Sunday 1 August 2010 at 5pm, Monday 2 August 2010 at 7.30pm Cameras, tape recorders, pagers, video recorders and mobile phones must not be operated during the performance. This concert will be recorded for broadcast. The Australian Brandenburg Orchestra is assisted The Australian Brandenburg by the Australian Government through the Australia Orchestra is assisted by the NSW Council, its arts funding and advisory body. Government through Arts NSW. PRINCIPAL PARTNER CORONATION PROGRAM_3.indd 1 22/07/10 1:05 PM Artistic Director's Message There is no doubt about it, the Brandenburg love the music of Handel! The Orchestra performed Handel in their very first concert and Handel features prominently on three of the Orchestra’s ARIA winning recordings. The important thing is, when it comes to Handel, you’re in good hands. Tonight, as part of our 21st birthday celebrations, we perform one of the most exhilarating choral works ever written, Handel’s Zadok the Priest. -

Music of the Renaissance and Baroque

Music of the Renaissance and Baroque A STUDY GUIDE FOR STUDENTS The music of Handel, Bach, Purcell and Carissimi 2 THE MUSIC OF HANDEL, BACH, PURCELL AND CARISSIMI Music of the Renaissance 3 Baroque Music 4 “Jephte” 4 “Come, Ye Sons of Art” 13 Cantata 4, “Christ lag in Todesbanden” 14 “Zadok the Priest” 18 Glossary of Terms 20 Credits 21 Questions for Discussion 21 __________________________________________________________________________________________ Prepared by John Neely, Music Director, The Bach Society of Dayton Ohio Created for the Muse Machine of Dayton, Ohio, in preparation for a collaboration with the Bach Society of Dayton for a concert on April 11, 2010. Concert: Sunday, April 11, 2010, 4:00 p.m. The Bach Society of Dayton and students of The Muse Machine with Chamber Orchestra Kettering Adventist Church 3939 Stonebridge Road (across from the Kettering Medical Center) “Come, Ye Sons of Art” – Henry Purcell Cantata 4, “Christ lag in Todesbanden” – Johann Sebastian Bach “Jephte” – Giacomo Carissimi Coronation Anthem: “Zadok the Priest” – George Frideric Handel Follow the Muse Date We are grateful for the generous support of these groups in the preparation of this study Please See guide and in the Bach Society’s collaboration with the Muse Machine in Project Sing. In Room For Ticket Info. 3 MUSIC OF THE RENAISSANCE 1400-1600 The word "Renaissance" is the French word for "rebirth." The Renaissance refers to the great rebirth of art and learning, which spread throughout Europe during the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. The period marked new discoveries in fine arts, music, literature, philosophy, science and technology, architecture, religion and spirituality.