Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shearer West Phd Thesis Vol 1

THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON (VOL. I) Shearer West A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 1986 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2982 This item is protected by original copyright THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON Ph.D. Thesis St. Andrews University Shearer West VOLUME 1 TEXT In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the I work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. ABSTRACT A theatrical portrait is an image of an actor or actors in character. This genre was widespread in eighteenth century London and was practised by a large number of painters and engravers of all levels of ability. The sources of the genre lay in a number of diverse styles of art, including the court portraits of Lely and Kneller and the fetes galantes of Watteau and Mercier. Three types of media for theatrical portraits were particularly prevalent in London, between ca745 and 1800 : painting, print and book illustration. -

Sex and Politics: Delarivier Manley's New Atalantis

Sex and Politics: Delarivier Manley’s New Atalantis Sex and Politics: Delarivier Manley’s New Atalantis Soňa Nováková Charles University, Prague Intellectual women during the Restoration and the Augustan age frequently participated in politics indirectly—by writing political satires and allegories. One of the most famous and influential examples is the Tory propagandist Delarivier Manley (1663-1724). Her writings reflect a self-consciousness about the diverse possibilities of propaganda and public self-representation. This paper focuses on her major and best-known work, The New Atalantis (1709) and reads Manley as an important transitional figure in the history of English political activity through print. Her political writings reflect a new model of political authority—not as divinely instituted and protected by subjects, but rather as open to contest via public representations, a result of the emerging public sphere. In her lifetime, Manley had achieved widespread fame as a writer of political scandal fiction. The New Atalantis, for example, riveted the attention of some of her most acclaimed contemporaries—Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Richard Steele, Jonathan Swift, and Alexander Pope who alluded to it in The Rape of the Lock (Canto III, ll.165-70). Nevertheless, Manley was also widely condemned. Many contemporary and later political opponents of Manley focus mainly on her sexual improprieties (she married her guardian only to discover it was a bigamous marriage, and later lived as mistress with her printer) and her critics disputed -

Restoration Verse Satires on Nell Gwyn As Life-Writing

This is a postprint! The Version of Record of this manuscript has been published and is available in Life Writing 13.4 (Taylor & Francis, 2016): 449-64. http://www.tandfonline.com/DOI: 10.1080/14484528.2015.1073715. ‘Rais’d from a Dunghill, to a King’s Embrace’: Restoration Verse Satires on Nell Gwyn as Life-Writing Dr. Julia Novak University of Salzburg Hertha Firnberg Research Fellow (FWF) Department of English and American Studies University of Salzburg Erzabt-Klotzstraße 1 5020 Salzburg AUSTRIA Tel. +43(0)699 81761689 Email: [email protected] This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under Grant T 589-G23. Abstract Nell Gwyn (1650-1687), one of the very early theatre actresses on the Restoration stage and long-term mistress to King Charles II, has today become a popular cultural icon, revered for her wit and good-naturedness. The image of Gwyn that emerges from Restoration satires, by contrast, is considerably more critical of the king’s actress-mistress. It is this image, arising from satiric references to and verse lives of Nell Gwyn, which forms the focus of this paper. Creating an image – a ‘likeness’ – of the subject is often cited as one of the chief purposes of biography. From the perspective of biography studies, this paper will probe to what extent Restoration verse satire can be read as life-writing and where it can be situated in the context of other 17th-century life-writing forms. It will examine which aspects of Gwyn’s life and character the satires address and what these choices reveal about the purposes of satire as a form of biographical storytelling. -

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American 'Revolution'

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American ‘Revolution’ Katherine Harper A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Arts Faculty, University of Sydney. March 27, 2014 For My Parents, To Whom I Owe Everything Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... i Abstract.......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One - ‘Classical Conditioning’: The Classical Tradition in Colonial America ..................... 23 The Usefulness of Knowledge ................................................................................... 24 Grammar Schools and Colleges ................................................................................ 26 General Populace ...................................................................................................... 38 Conclusions ............................................................................................................... 45 Chapter Two - Cato in the Colonies: Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................... 47 Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................................................... 49 The Universal Appeal of Virtue ........................................................................... -

Copyright by Katharine Elizabeth Beutner 2011

Copyright by Katharine Elizabeth Beutner 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Katharine Elizabeth Beutner certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Writing for Pleasure or Necessity: Conflict among Literary Women, 1700-1750 Committee: ____________________________________ Lance Bertelsen, Supervisor ____________________________________ Janine Barchas ____________________________________ Elizabeth Cullingford ____________________________________ Margaret Ezell ____________________________________ Catherine Ingrassia Writing for Pleasure or Necessity: Conflict among Literary Women, 1700-1750 by Katharine Elizabeth Beutner, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Acknowledgments My thanks to the members of my dissertation committee—Janine Barchas, Elizabeth Cullingford, Margaret Ezell, and Catherine Ingrassia—for their wise and patient guidance as I completed this project. Thanks are also due to Elizabeth Hedrick, Michael Adams, Elizabeth Harris, Tom Cable, Samuel Baker, and Wayne Lesser for all the ways they’ve shaped my graduate career. Kathryn King, Patricia Hamilton, Jennie Batchelor, and Susan Carlile encouraged my studies of eighteenth-century women writers; Al Coppola graciously sent me a copy of his article on Eliza Haywood’s Works pre-publication. Thanks to Matthew Reilly for comments on an early version of the Manley material and to Jessica Kilgore for advice and good cheer. My final year of writing was supported by the Carolyn Lindley Cooley, Ph.D. Named PEO Scholar Award and by a Dissertation Fellowship from the American Association of University Women. I want to express my gratitude to both organizations. -

Weaver, Words, and Dancing in the Judgment of Paris

On Common Ground 5:Weaver, Dance inWords, Drama, and Drama Dancing in in DanceThe Judgment of Paris DHDS March 2005 Text copyright © Moira Goff and DHDS 2005 Weaver, Words, and Dancing in The Judgment of Paris Moira Goff On 31 January 1733, the Daily Post let its readers know that ‘The Judgment of Paris, which was intended to be perform’d this Night, is deferr’d for a few Days, upon Account of some Alterations in the Machinery’. John Weaver’s new afterpiece, which was to be his last work for the London stage, received its first performance at Drury Lane on 6 February 1733.1 Weaver had not created a serious dance work since his ‘Dramatic Entertainments of Danc- ing’ The Loves of Mars and Venus of 1717 and Orpheus and Eurydice of 1718. When the description for The Judgment of Paris was published to accompany performances, it an- nounced a change from Weaver’s earlier practice by referring to the work as a ‘Dramatic Entertainment in Dancing and Singing’.2 Why did Weaver resort to words? Did he feel that they were necessary to attract audiences and explain the story to them? The Judgment of Paris was performed six times between 6 and 15 February 1733, and then dropped out of the repertoire. On 31 March The Harlot’s Progress; or, The Ridotto Al’Fresco was given its first performance. This afterpiece by Theophilus Cibber, based on the very popular series of paintings and prints by William Hogarth, included a ‘Grand Masque call’d, The Judgment of Paris’. -

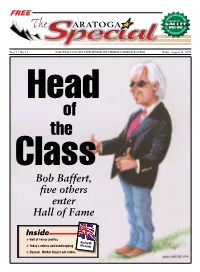

Bob Baffert, Five Others Enter Hall of Fame

FREE SUBSCR ER IPT IN IO A N R S T COMPLIMENTS OF T !2!4/'! O L T IA H C E E 4HE S SP ARATOGA Year 9 • No. 15 SARATOGA’S DAILY NEWSPAPER ON THOROUGHBRED RACING Friday, August 14, 2009 Head of the Class Bob Baffert, five others enter Hall of Fame Inside F Hall of Famer profiles Racing UK F Today’s entries and handicapping PPs Inside F Dynaski, Mother Russia win stakes DON’T BOTHER CHECKING THE PHOTO, THE WINNER IS ALWAYS THE SAME. YOU WIN. You win because that it generates maximum you love explosive excitement. revenue for all stakeholders— You win because AEG’s proposal including you. AEG’s proposal to upgrade Aqueduct into a puts money in your pocket world-class destination ensuress faster than any other bidder, tremendous benefits for you, thee ensuring the future of thorough- New York Racing Associationn bred racing right here at home. (NYRA), and New York Horsemen, Breeders, and racing fans. THOROUGHBRED RACING MUSEUM. AEG’s Aqueduct Gaming and Entertainment Facility will have AEG’s proposal includes a Thoroughbred Horse Racing a dazzling array Museum that will highlight and inform patrons of the of activities for VLT REVENUE wonderful history of gaming, dining, VLT OPERATION the sport here in % retail, and enter- 30 New York. tainment which LOTTERY % AEG The proposed Aqueduct complex will serve as a 10 will bring New world-class gaming and entertainment destination. DELIVERS. Yorkers and visitors from the Tri-State area and beyond back RACING % % AEG is well- SUPPORT 16 44 time and time again for more fun and excitement. -

Aeneid 7 Page 1 the BIRTH of WAR -- a Reading of Aeneid 7 Sara Mack

Birth of War – Aeneid 7 page 1 THE BIRTH OF WAR -- A Reading of Aeneid 7 Sara Mack In this essay I will touch on aspects of Book 7 that readers are likely either to have trouble with (the Muse Erato, for one) or not to notice at all (the founding of Ardea is a prime example), rather than on major elements of plot. I will also look at some of the intertexts suggested by Virgil's allusions to other poets and to his own poetry. We know that Virgil wrote with immense care, finishing fewer than three verses a day over a ten-year period, and we know that he is one of the most allusive (and elusive) of Roman poets, all of whom wrote with an eye and an ear on their Greek and Roman predecessors. We twentieth-century readers do not have in our heads what Virgil seems to have expected his Augustan readers to have in theirs (Homer, Aeschylus, Euripides, Apollonius, Lucretius, and Catullus, to name just a few); reading the Aeneid with an eye to what Virgil has "stolen" from others can enhance our enjoyment of the poem. Book 7 is a new beginning. So the Erato invocation, parallel to the invocation of the Muse in Book 1, seems to indicate. I shall begin my discussion of the book with an extended look at some of the implications of the Erato passage. These difficult lines make a good introduction to the themes of the book as a whole (to the themes of the whole second half of the poem, in fact). -

Season of 1703-04 (Including the Summer Season of 1704), the Drury Lane Company Mounted 64 Mainpieces and One Medley on a Total of 177 Nights

Season of 1703-1704 n the surface, this was a very quiet season. Tugging and hauling occur- O red behind the scenes, but the two companies coexisted quite politely for most of the year until a sour prologue exchange occurred in July. Our records for Drury Lane are virtually complete. They are much less so for Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which advertised almost not at all until 18 January 1704. At that time someone clearly made a decision to emulate Drury Lane’s policy of ad- vertising in London’s one daily paper. Neither this season nor the next did the LIF/Queen’s company advertise every day, but the ads become regular enough that we start to get a reasonable idea of their repertory. Both com- panies apparently permitted a lot of actor benefits during the autumn—pro- bably a sign of scanty receipts and short-paid salaries. Throughout the season advertisements make plain that both companies relied heavily on entr’acte song and dance to pull in an audience. Newspaper bills almost always mention singing and dancing, sometimes specifying the items in considerable detail, whereas casts are never advertised. Occasionally one or two performers will be featured, but at this date the cast seems not to have been conceived as the basic draw. Or perhaps the managers were merely economizing, treating newspaper advertisements as the equivalent of handbills rather than “Great Bills.” The importance of music to the public at this time is also evident in the numerous concerts of various sorts on offer, and in the founding of The Monthly Mask of Vocal Musick, a periodical devoted to printing new songs, including some from the theatre.1 One of the most interesting developments of this season is a ten-concert series generally advertised as “The Subscription Musick.” So far as we are aware, it has attracted no scholarly commentary whatever, but it may well be the first series of its kind in the history of music in London. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

An A2 Timeline of the London Stage Between 1660 and 1737

1660-61 1659-60 1661-62 1662-63 1663-64 1664-65 1665-66 1666-67 William Beeston The United Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company @ Salisbury Court Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company & Thomas Killigrew @ Salisbury Court @Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Rhodes’s Company @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Red Bull Theatre @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields George Jolly John Rhodes @ Salisbury Court @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane The King’s Company The King’s Company PLAGUE The King’s Company The King’s Company The King’s Company Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew June 1665-October 1666 Anthony Turner Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew @ Vere Street Theatre @ Vere Street Theatre & Edward Shatterell @ Red Bull Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Bridges Street Theatre, GREAT FIRE @ Red Bull Theatre Drury Lane (from 7/5/1663) The Red Bull Players The Nursery @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane September 1666 @ Red Bull Theatre George Jolly @ Hatton Garden 1676-77 1675-76 1674-75 1673-74 1672-73 1671-72 1670-71 1669-70 1668-69 1667-68 The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company Thomas Betterton & William Henry Harrison and Thomas Henry Harrison & Thomas Sir William Davenant Smith for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields -

Santa Anita Derby

$$750,0001,0000,000 SANTA ANITA HANDICAP SANTA ANITA DERBY GAME ON DUDE Dear Member of the Media: Now in its 78th year of Thoroughbred racing, Santa Anita is proud to have hosted many of the sport’s greatest moments. Although the names of its historic human and horse heroes may have changed in the SANTA ANITA HANDICAP past seven decades of racing, Santa Anita’s prominence in the sport $1,000,000 Guaranteed (Grade I) remains constant. Saturday, March 7, 2015 • Seventy-Eighth Running This year, Santa Anita will present the 78th edition of one of rac- Gross Purse: $1,000,000 Winner’s Share: $600,000 Other Awards: $200,000 second; $120,000 third; $50,000 fourth; $20,000 fifth ing’s premier races — the $1,000,000 Santa Anita Handicap on Saturday, Distance: One and one-quarter miles on the main track March 7. Nominations: Close February 21, 2015 at $100 each The historic Big ‘Cap was the nation’s first continually run $100,000 Supplementary nominations of $25,000 by 12 noon, Feb. 28, 2015 Track and American stakes race and has arguably had more impact on the progress of Dirt Record: 1:57 4/5, Spectacular Bid, 4 (Bill Shoemaker, 126, February 3, Thoroughbred racing than any other single event in the sport. The 1980, Charles H. Strub Stakes) importance of this race and many of its highlights are detailed by the Stakes Record: 1:58 3/5, Affirmed, 4 (Laffit Pincay Jr., 128, March 4, 1979) Gates Open: 10:00 a.m. esteemed sports journalist John Hall beginning on page 2.