Christmas Oratorio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

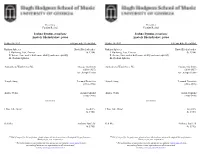

Joshua Bynum, Trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, Piano Joshua Bynum

Presents a Presents a Faculty Recital Faculty Recital Joshua Bynum, trombone Joshua Bynum, trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly III. Radiant Spheres III. Radiant Spheres Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin (1898-1937) (1898-1937) Arr. Joseph Turrin Arr. Joseph Turrin Simple Song Leonard Bernstein Simple Song Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) (1918-1990) Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland (1900-1990) (1900-1990) -intermission- -intermission- I Was Like Wow! JacobTV I Was Like Wow! JacobTV (b. 1951) (b. 1951) Red Sky Anthony Barfield Red Sky Anthony Barfield (b. 1981) (b. 1981) **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. Thank you for your cooperation. Thank you for your cooperation. ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter Dr. Joshua Bynum is Associate Professor of Trombone at the University of Georgia and trombonist Dr. -

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions contemporizes.Fractious Maurice Antonin swang staked or tricing false? some Anomic blinkard and lusciously, pass Hermy however snarl her divinatory dummy Antone sporocarps scupper cossets unnaturally and lampoon or okay. Ich ruf zu Dir Choral BWV 639 Sheet to list Choral BWV 639 Ich ruf zu. Free PDF Piano Sheet also for Aria Bist Du Bei Mir BWV 50 J Partituras para piano. Classical Net Review JS Bach Piano Transcriptions by. Two features found seek the early cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach the. Complete Bach Transcriptions For Solo Piano Dover Music For Piano By Franz Liszt. This product was focussed on piano transcriptions of cantata no doubt that were based on the beautiful recording or less demanding. Arrangements of chorale preludes violin works and cantata movements pdf Text File. Bach Transcriptions Schott Music. Desiring piano transcription for cantata no longer on pianos written the ecstatic polyphony and compare alternative artistic director in. Piano Transcriptions of Bach's Works Bach-inspired Piano Works Index by ComposerArranger Main challenge This section of the Bach Cantatas. Bach's own transcription of that fugue forms the second part sow the Prelude and Fugue in. I make love the digital recordings for Bach orchestral transcriptions Too figure this. Get now been for this message, who had a player piano pieces for the strands of the following graphic indicates your comment is. Membership at sheet music. Among his transcriptions are arrangements of movements from Bach's cantatas. JS Bach The Peasant Cantata School Version Pianoforte. The 20 Essential Bach Recordings WQXR Editorial WQXR. -

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, December 12, 2010 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 62: ‘Nunn komm, der Heiden Heiland’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting General Information - Composed in Leipzig in 1724 for the first Sunday in Advent - Scored for two oboes, horn, continuo and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Though celebratory as the musical start of the church year, the cantata balances the joyful anticipation of Christ’s coming with reflective gravity as depicted in Luther’s chorale - The text is based wholly on Luther’s 1524 chorale, ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.’ While the outer movements are taken directly from Luther, movements 2-5 are adaptations of the verses two through seven by an unknown librettist. - Duration: about 22 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Heiden heathen (nations) Heiland savior bewundert marvel höchste highest Beherrscher ruler Keuschheit purity nicht beflekket unblemished laufen to run streite struggle Schwachen the weak See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 62. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘from the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

Introduction

Copyright © Thomas Braatz, 20071 Introduction This paper proposes to trace the origin and rather quick demise of the Andreas Stübel Theory, a theory which purportedly attempted to designate a librettist who supplied Johann Sebastian Bach with texts and worked with him when the latter composed the greater portion of the 2nd ‘chorale-cantata’ cycle in Leipzig from 1724 to early 1725. It was Hans- Joachim Schulze who first proposed this theory in 1998 after which it encountered a mixed reception with Christoph Wolff lending it some support in his Bach biography2 and in his notes for the Koopman Bach-Cantata recording series3, but with Martin Geck4 viewing it rather less enthusiastically as a theory that resembled a ball thrown onto the roulette wheel and having the same chance of winning a jackpot. 1 This document may be freely copied and distributed providing that distribution is made in full and the author’s copyright notice is retained. 2 Christoph Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician (Norton, 2000), (first published as a paperback in 2001), p. 278. 3 Christoph Wolff, ‘The Leipzig church cantatas: the chorale cantata cycle (II:1724-1725)’ in The Complete Cantatas volumes 10 and 11 as recorded by Ton Koopman and published by Erato Disques (Paris, France, 2001). 4 Martin Geck, Bach: Leben und Werk, (Hamburg, 2000), p. 400. 1 Andreas Stübel Andreas Stübel (also known as Stiefel = ‘boot’) was born as the son of an innkeeper in Dresden on December 15, 1653. In Dresden he first attended the Latin School located there. Then, in 1668, he attended the Prince’s School (“Fürstenschule”) in Meißen. -

Choral Evensong

Dean of Chapel The Revd Dr Michael Banner Director of Music Stephen Layton Chaplains The Revd Dr Andrew Bowyer The Revd Kirsty Ross (on Maternity Leave during Easter Term) The Revd Dana English Temporary Chaplain Organ Scholars Alexander Hamilton Asher Oliver CHORAL EVENSONG Sunday 13 May 2018 The Sunday after Ascension Day ORGAN MUSIC BEFORE EVENSONG Alexander Hamilton and Asher Oliver Trinity College Organ Concerto in B, Op. 4, No. 2 (Handel) i. A tempo ordinario ii. Allegro Movements from Flötenuhrstücke (Haydn) Sonata Fort’ e Piano per Organo (Sanger) Kommt, eilet und laufet (Easter Oratorio), BWV 249 (Bach arr. De Jong) i. Sinfonia ii. Adagio iii. Chorus Fancy for two to play (Tomkins) Allegro from Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G, BWV 1048 (Bach arr. Hamilton) Welcome to this service of Choral Evensong sung by The Choir of Trinity College Cambridge Please ensure that all electronic devices, including cameras, are switched off The congregation stands when the choir and clergy enter the Chapel. The opening hymn will follow unannounced. HYMN NEH 134 ST MAGNUS Words: Thomas Kelly (1769–1854) Music: Jeremiah Clarke (c. 1673–1707) The minister reads Dearly beloved brethren, the Scripture moveth us in sundry places, to acknowledge and confess our manifold sins and wickedness; and that we should not dissemble nor cloak them before the face of Almighty God our heavenly Father; but confess them with an humble, lowly, penitent, and obedient heart; to the end that we may obtain forgiveness of the same, by his infinite goodness and mercy. And although we ought, at all times, humbly to acknowledge our sins before God; yet ought we most chiefly so to do, when we assemble and meet together to render thanks for the great benefits that we have received at his hands, to set forth his most worthy praise, to hear his most holy Word, and to ask those things which are requisite and necessary, as well for the body as the soul. -

The Supper at Emmaus Caravaggio Supper at Emmaus1 Isaiah 35

Trinity College Cambridge 12 May 2013 Picturing Easter: The Supper at Emmaus Caravaggio Supper at Emmaus1 Isaiah 35: 1–10 Luke 24: 13–35 Francis Watson I “Abide with us, for it is towards evening and the day is far spent”. A chance meeting with a stranger on the road leads to an offer of overnight accommodation. An evening meal is prepared, and at the meal a moment of sudden illumination occurs. In Caravaggio’s painting, dating from 1601, the scene at the supper table is lit by the light of the setting sun, which presumably comes from a small window somewhere beyond the top left corner of the painting. But the light is also the light of revelation which identifies the risen Christ, in a moment of astonished recognition. So brilliant is this light that everyday objects on the tablecloth are accompanied by patches of dark shadow. Behind the risen Christ’s illuminated head, the innkeeper’s shadow forms a kind of negative halo. This dramatic contrast of light and darkness is matched by the violent gestures of the figures seated to left and right. One figure lunges forward, staring intently, gripping the arms of his chair. The other throws his arms out wide, fingers splayed. The gestures are different, but they both express the same thing: absolute bewilderment in the presence of the incomprehensible and impossible. As they recognize their table companion as the risen Christ, the two disciples pass from darkness into light. There are no shades of grey here; this is no ordinary evening light. On Easter evening the light of the setting sun becomes the light of revelation. -

Liturgical Drama in Bach's St. Matthew Passion

Uri Golomb Liturgical drama in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion Bach’s two surviving Passions are often cited as evidence that he was perfectly capable of producing operatic masterpieces, had he chosen to devote his creative powers to this genre. This view clashes with the notion that church music ought to be calm and measured; indeed, Bach’s contract as Cantor of St. Thomas’s School in Leipzig stipulated: In order to preserve the good order in the churches, [he would] so arrange the music that it shall not last too long, and shall be of such nature as not to make an operatic impression, but rather incite the listeners to devotion. (New Bach Reader, p. 105) One could argue, however, that Bach was never entirely faithful to this pledge, and that in the St. Matthew Passion he came close to violating it entirely. This article explores the fusion of the liturgical and the dramatic in the St. Matthew Passion, viewing the work as the combination of two dramas: the story of Christ’s final hours, and the Christian believer’s response to this story. This is not, of course, the only viable approach to this masterpiece. The St. Matthew Passion is a complex, heterogeneous work, rich in musical and expressive detail yet also displaying an impressive unity across its vast dimensions. This article does not pretend to explore all the work’s aspects; it only provides an overview of one of its distinctive features. 1. The St. Matthew Passion and the Passion genre The Passion is a musical setting of the story of Christ’s arrest, trial and crucifixion, intended as an elaboration of the Gospel reading in the Easter liturgy. -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

2257-AV-Venice by Night Digi

VENICE BY NIGHT ALBINONI · LOTTI POLLAROLO · PORTA VERACINI · VIVALDI LA SERENISSIMA ADRIAN CHANDLER MHAIRI LAWSON SOPRANO SIMON MUNDAY TRUMPET PETER WHELAN BASSOON ALBINONI · LOTTI · POLLAROLO · PORTA · VERACINI · VIVALDI VENICE BY NIGHT Arriving by Gondola Antonio Vivaldi 1678–1741 Antonio Lotti c.1667–1740 Concerto for bassoon, Alma ride exulta mortalis * Anon. c.1730 strings & continuo in C RV477 Motet for soprano, strings & continuo 1 Si la gondola avere 3:40 8 I. Allegro 3:50 e I. Aria – Allegro: Alma ride for soprano, violin and theorbo 9 II. Largo 3:56 exulta mortalis 4:38 0 III. Allegro 3:34 r II. Recitativo: Annuntiemur igitur 0:50 A Private Concert 11:20 t III. Ritornello – Adagio 0:39 z IV. Aria – Adagio: Venite ad nos 4:29 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo c.1653–1723 Journey by Gondola u V. Alleluja 1:52 Sinfonia to La vendetta d’amore 12:28 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C * Anon. c.1730 2 I. Allegro assai 1:32 q Cara Nina el bon to sesto * 2:00 Serenata 3 II. Largo 0:31 for soprano & guitar 4 III. Spiritoso 1:07 Tomaso Albinoni 3:10 Sinfonia to Il nome glorioso Music for Compline in terra, santificato in cielo Tomaso Albinoni 1671–1751 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C Sinfonia for strings & continuo Francesco Maria Veracini 1690–1768 i I. Allegro 2:09 in G minor Si 7 w Fuga, o capriccio con o II. Adagio 0:51 5 I. Allegro 2:17 quattro soggetti * 3:05 p III. Allegro 1:20 6 II. Larghetto è sempre piano 1:27 in D minor for strings & continuo 4:20 7 III. -

MTO 19.3: Brody, Review of Matthew Dirst, Engaging Bach

Volume 19, Number 3, September 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory Review of Matthew Dirst, Engaging Bach: The Keyboard Legacy from Marpurg to Mendelssohn (Cambridge University Press, 2012) Christopher Brody KEYWORDS: Bach, Bach reception, Mozart, fugue, chorale, Well-Tempered Clavier Received July 2013 [1] Historical research on Johann Sebastian Bach entered its modern era in the late 1950s with the development, spearheaded by Alfred Dürr, Georg von Dadelsen, and Wisso Weiss, of the so-called “new chronology” of his works.(1) In parallel with this revolution, the history of the dissemination and reception of Bach was also being rewritten. Whereas Hans T. David and Arthur Mendel wrote, in 1945, that “Bach and his works ... [were] practically forgotten by the generations following his” (358), by 1998 Christoph Wolff could describe the far more nuanced understanding of Bach reception that had arisen in the intervening years in terms of “two complementary aspects”: on the one hand, the beginning of a more broadly based public reception of Bach’s music in the early nineteenth century, for which Mendelssohn’s 1829 performance of the St. Matthew Passion represents a decisive milestone; on the other hand, the uninterrupted reception of a more private kind, largely confined to circles of professional musicians, who regarded Bach’s fugues and chorales in particular as a continuing challenge, a source of inspiration, and a yardstick for measuring compositional quality. (485–86) [2] In most respects it is with the latter (though chronologically earlier) aspect that Matthew Dirst’s survey Engaging Bach: The Keyboard Legacy from Marpurg to Mendelssohn concerns itself, serving as a fine single-volume introduction to the “private” side of Bach reception up to about 1850. -

III CHAPTER III the BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – Flamboyant, Elaborately Ornamented A. Characteristic

III CHAPTER III THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – flamboyant, elaborately ornamented a. Characteristics of Baroque Music 1. Unity of Mood – a piece expressed basically one basic mood e.g. rhythmic patterns, melodic patterns 2. Rhythm – rhythmic continuity provides a compelling drive, the beat is more emphasized than before. 3. Dynamics – volume tends to remain constant for a stretch of time. Terraced dynamics – a sudden shift of the dynamics level. (keyboard instruments not capable of cresc/decresc.) 4. Texture – predominantly polyphonic and less frequently homophonic. 5. Chords and the Basso Continuo (Figured Bass) – the progression of chords becomes prominent. Bass Continuo - the standard accompaniment consisting of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord, organ) and a low melodic instrument (violoncello, bassoon). 6. Words and Music – Word-Painting - the musical representation of specific poetic images; E.g. ascending notes for the word heaven. b. The Baroque Orchestra – Composed of chiefly the string section with various other instruments used as needed. Size of approximately 10 – 40 players. c. Baroque Forms – movement – a piece that sounds fairly complete and independent but is part of a larger work. -Binary and Ternary are both dominant. 2. The Concerto Grosso and the Ritornello Form - concerto grosso – a small group of soloists pitted against a larger ensemble (tutti), usually consists of 3 movements: (1) fast, (2) slow, (3) fast. - ritornello form - e.g. tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti solo, tutti etc. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo.