THE BACH EXPERIENCE Performed During the Interdenominational Protestant Worship Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choral Evensong

Dean of Chapel The Revd Dr Michael Banner Director of Music Stephen Layton Chaplains The Revd Dr Andrew Bowyer The Revd Kirsty Ross (on Maternity Leave during Easter Term) The Revd Dana English Temporary Chaplain Organ Scholars Alexander Hamilton Asher Oliver CHORAL EVENSONG Sunday 13 May 2018 The Sunday after Ascension Day ORGAN MUSIC BEFORE EVENSONG Alexander Hamilton and Asher Oliver Trinity College Organ Concerto in B, Op. 4, No. 2 (Handel) i. A tempo ordinario ii. Allegro Movements from Flötenuhrstücke (Haydn) Sonata Fort’ e Piano per Organo (Sanger) Kommt, eilet und laufet (Easter Oratorio), BWV 249 (Bach arr. De Jong) i. Sinfonia ii. Adagio iii. Chorus Fancy for two to play (Tomkins) Allegro from Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G, BWV 1048 (Bach arr. Hamilton) Welcome to this service of Choral Evensong sung by The Choir of Trinity College Cambridge Please ensure that all electronic devices, including cameras, are switched off The congregation stands when the choir and clergy enter the Chapel. The opening hymn will follow unannounced. HYMN NEH 134 ST MAGNUS Words: Thomas Kelly (1769–1854) Music: Jeremiah Clarke (c. 1673–1707) The minister reads Dearly beloved brethren, the Scripture moveth us in sundry places, to acknowledge and confess our manifold sins and wickedness; and that we should not dissemble nor cloak them before the face of Almighty God our heavenly Father; but confess them with an humble, lowly, penitent, and obedient heart; to the end that we may obtain forgiveness of the same, by his infinite goodness and mercy. And although we ought, at all times, humbly to acknowledge our sins before God; yet ought we most chiefly so to do, when we assemble and meet together to render thanks for the great benefits that we have received at his hands, to set forth his most worthy praise, to hear his most holy Word, and to ask those things which are requisite and necessary, as well for the body as the soul. -

The Supper at Emmaus Caravaggio Supper at Emmaus1 Isaiah 35

Trinity College Cambridge 12 May 2013 Picturing Easter: The Supper at Emmaus Caravaggio Supper at Emmaus1 Isaiah 35: 1–10 Luke 24: 13–35 Francis Watson I “Abide with us, for it is towards evening and the day is far spent”. A chance meeting with a stranger on the road leads to an offer of overnight accommodation. An evening meal is prepared, and at the meal a moment of sudden illumination occurs. In Caravaggio’s painting, dating from 1601, the scene at the supper table is lit by the light of the setting sun, which presumably comes from a small window somewhere beyond the top left corner of the painting. But the light is also the light of revelation which identifies the risen Christ, in a moment of astonished recognition. So brilliant is this light that everyday objects on the tablecloth are accompanied by patches of dark shadow. Behind the risen Christ’s illuminated head, the innkeeper’s shadow forms a kind of negative halo. This dramatic contrast of light and darkness is matched by the violent gestures of the figures seated to left and right. One figure lunges forward, staring intently, gripping the arms of his chair. The other throws his arms out wide, fingers splayed. The gestures are different, but they both express the same thing: absolute bewilderment in the presence of the incomprehensible and impossible. As they recognize their table companion as the risen Christ, the two disciples pass from darkness into light. There are no shades of grey here; this is no ordinary evening light. On Easter evening the light of the setting sun becomes the light of revelation. -

Liturgical Drama in Bach's St. Matthew Passion

Uri Golomb Liturgical drama in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion Bach’s two surviving Passions are often cited as evidence that he was perfectly capable of producing operatic masterpieces, had he chosen to devote his creative powers to this genre. This view clashes with the notion that church music ought to be calm and measured; indeed, Bach’s contract as Cantor of St. Thomas’s School in Leipzig stipulated: In order to preserve the good order in the churches, [he would] so arrange the music that it shall not last too long, and shall be of such nature as not to make an operatic impression, but rather incite the listeners to devotion. (New Bach Reader, p. 105) One could argue, however, that Bach was never entirely faithful to this pledge, and that in the St. Matthew Passion he came close to violating it entirely. This article explores the fusion of the liturgical and the dramatic in the St. Matthew Passion, viewing the work as the combination of two dramas: the story of Christ’s final hours, and the Christian believer’s response to this story. This is not, of course, the only viable approach to this masterpiece. The St. Matthew Passion is a complex, heterogeneous work, rich in musical and expressive detail yet also displaying an impressive unity across its vast dimensions. This article does not pretend to explore all the work’s aspects; it only provides an overview of one of its distinctive features. 1. The St. Matthew Passion and the Passion genre The Passion is a musical setting of the story of Christ’s arrest, trial and crucifixion, intended as an elaboration of the Gospel reading in the Easter liturgy. -

Concert Season 34

Concert Season 34 REVISED CALENDAR 2020 2021 Note from the Maestro eAfter an abbreviated Season 33, VoxAmaDeus returns for its 34th year with a renewed dedication to bringing you a diverse array of extraordinary concerts. It is with real pleasure that we look forward, once again, to returning to the stage and regaling our audiences with the fabulous programs that have been prepared for our three VoxAmaDeus performing groups. (Note that all fall concerts will be of shortened duration in light of current guidelines.) In this year of necessary breaks from tradition, our season opener in mid- September will be an intimate Maestro & Guests concert, September Soirée, featuring delightful solo works for piano, violin and oboe, in the spacious and acoustically superb St. Katharine of Siena Church in Wayne. Vox Renaissance Consort will continue with its trio of traditional Renaissance Noël concerts (including return to St. Katharine of Siena Church) that bring you back in time to the glory of Old Europe, with lavish costumes and period instruments, and heavenly music of Italian, English and German masters. Ama Deus Ensemble will perform five fascinating concerts. First is the traditional December Handel Messiah on Baroque instruments, but for this year shortened to 80 minutes and consisting of highlights from all three parts. Then, for our Good Friday concert in April, a program of sublime music, Bach Easter Oratorio & Rossini Stabat Mater; in May, two glorious Beethoven works, the Fifth Symphony and the Missa solemnis; and, lastly, two programs in June: Bach & Vivaldi Festival, as well as our Season 34 Grand Finale Gershwin & More (transplanted from January to June, as a temporary break from tradition), an exhilarating concert featuring favorite works by Gershwin, with the amazing Peter Donohoe as piano soloist, and also including rousing movie themes by Hans Zimmer and John Williams. -

The Orchestra in History

Jeremy Montagu The Orchestra in History The Orchestra in History A Lecture Series given in the late 1980s Jeremy Montagu © Jeremy Montagu 2017 Contents 1 The beginnings 1 2 The High Baroque 17 3 The Brandenburg Concertos 35 4 The Great Change 49 5 The Classical Period — Mozart & Haydn 69 6 Beethoven and Schubert 87 7 Berlioz and Wagner 105 8 Modern Times — The Age Of The Dinosaurs 125 Bibliography 147 v 1 The beginnings It is difficult to say when the history of the orchestra begins, be- cause of the question: where does the orchestra start? And even, what is an orchestra? Does the Morley Consort Lessons count as an orchestra? What about Gabrieli with a couple of brass choirs, or even four brass choirs, belting it out at each other across the nave of San Marco? Or the vast resources of the Striggio etc Royal Wedding and the Florentine Intermedii, which seem to have included the original four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie, or at least a group of musicians popping out of the pastry. I’m not sure that any of these count as orchestras. The Morley Consort Lessons are a chamber group playing at home; Gabrieli’s lot wasn’t really an orchestra; The Royal Wed- dings and so forth were a lot of small groups, of the usual renais- sance sorts, playing in turn. Where I am inclined to start is with the first major opera, Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo. Even that tends to be the usual renaissance groups taking turn about, but they are all there in a coherent dra- matic structure, and they certainly add up to an orchestra. -

WOODWIND INSTRUMENT 2,151,337 a 3/1939 Selmer 2,501,388 a * 3/1950 Holland

United States Patent This PDF file contains a digital copy of a United States patent that relates to the Native American Flute. It is part of a collection of Native American Flute resources available at the web site http://www.Flutopedia.com/. As part of the Flutopedia effort, extensive metadata information has been encoded into this file (see File/Properties for title, author, citation, right management, etc.). You can use text search on this document, based on the OCR facility in Adobe Acrobat 9 Pro. Also, all fonts have been embedded, so this file should display identically on various systems. Based on our best efforts, we believe that providing this material from Flutopedia.com to users in the United States does not violate any legal rights. However, please do not assume that it is legal to use this material outside the United States or for any use other than for your own personal use for research and self-enrichment. Also, we cannot offer guidance as to whether any specific use of any particular material is allowed. If you have any questions about this document or issues with its distribution, please visit http://www.Flutopedia.com/, which has information on how to contact us. Contributing Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office - http://www.uspto.gov/ Digitizing Sponsor: Patent Fetcher - http://www.PatentFetcher.com/ Digitized by: Stroke of Color, Inc. Document downloaded: December 5, 2009 Updated: May 31, 2010 by Clint Goss [[email protected]] 111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US007563970B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,563,970 B2 Laukat et al. -

Bach Easter Oratorio BWV 249 (Novello Edition Ed. N. Jenkins)

PROGRAMME NOTES AND PREFACES Bach Easter Oratorio BWV 249 (Novello edition ed. N. Jenkins) HISTORY AND ORIGINS OF THE WORK Bach composed many pieces of celebratory musc during his time in Leipzig. Some were Birthday Odes for members of the ruling family. As these were only destined to receive one performance it is not surprising to find movements from them reappearing in the church cantatas which he had to provide each week for the St. Thomas choir. Thus a large work like the Christmas Oratorio is principally made up out of at least 3 celebratory birthday cantatas. i1 Bach knew a good thing when he saw it, and was determined to find a new home for some of the large-scale choral and orchestral movements into which he had put so much creative effort. In the case of the Easter Oratorio it is even likely that he planned a dual use for this music from the inception, since he makes use of all the movements in sequence in his reworking of it as church cantata. It started life as a secular birthday cantata for Christian, Duke of Sachs-Weißenfels with the opening text Entfliehet, verschwindet, entweichet, ihr Sorgen [BWV 249a] and was performed on 23rd February 1725. As with all of these cantatas (including the Christmas Oratorio ones) it started and ended with loud celebratory movements employing the town’s trumpeters and drums, of which the last one called for a full chorus as well. These pieces were sometimes performed in the open air, where such an instrumentation was particularly effective. -

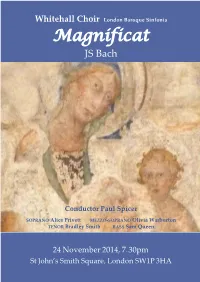

Magnificat JS Bach

Whitehall Choir London Baroque Sinfonia Magnificat JS Bach Conductor Paul Spicer SOPRANO Alice Privett MEZZO-SOPRANO Olivia Warburton TENOR Bradley Smith BASS Sam Queen 24 November 2014, 7. 30pm St John’s Smith Square, London SW1P 3HA In accordance with the requirements of Westminster City Council persons shall not be permitted to sit or stand in any gangway. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment is strictly forbidden without formal consent from St John’s. Smoking is not permitted anywhere in St John’s. Refreshments are permitted only in the restaurant in the Crypt. Please ensure that all digital watch alarms, pagers and mobile phones are switched off. During the interval and after the concert the restaurant is open for licensed refreshments. Box Office Tel: 020 7222 1061 www.sjss.org.uk/ St John’s Smith Square Charitable Trust, registered charity no: 1045390. Registered in England. Company no: 3028678. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Choir is very grateful for the support it continues to receive from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS). The Choir would like to thank Philip Pratley, the Concert Manager, and all tonight’s volunteer helpers. We are grateful to Hertfordshire Libraries’ Performing Arts service for the supply of hire music used in this concert. The image on the front of the programme is from a photograph taken by choir member Ruth Eastman of the Madonna fresco in the Papal Palace in Avignon. WHITEHALL CHOIR - FORTHCOMING EVENTS (For further details visit www.whitehallchoir.org.uk.) Tuesday, 16 -

J. S. Bach Christmas Oratorio

J. S. BACH CHRISTMAS ORATORIO Bach Collegium Japan Masaaki Suzuki BACH, Johann Sebastian (1685–1750) Weihnachtsoratorium, BWV 248 142'19 (Christmas Oratorio) Disc 1 Part I: Jauchzet, frohlocket! auf, preiset die Tage 24'57 Christmas Day (25th December 1734) 1 1. Chor. Jauchzet, frohlocket! auf, preiset die Tage … 7'35 2 2. Rezitativ (Tenor [Evangelist]). Es begab sich aber zu der Zeit … 1'14 3 3. Rezitativ (Alt). Nun wird mein liebster Bräutigam … 0'56 4 4. Arie (Alt). Bereite dich, Zion … 5'05 5 5. Choral. Wie soll ich dich empfangen … 1'05 6 6. Rezitativ (Tenor [Evangelist]). Und sie gebar ihren ersten Sohn … 0'24 7 7. Choral und Rezitativ (Sopran, Bass). Er ist auf Erden kommen arm … 2'46 8 8. Arie (Bass). Großer Herr, o starker König … 4'30 9 9. Choral. Ach, mein herzliebes Jesulein … 1'10 Part II: Und es waren Hirten in derselben Gegend 28'31 Second Day of Christmas (26th December 1734) 10 10. Sinfonia 5'42 11 11. Rezitativ (Tenor [Evangelist]). Und es waren Hirten in derselben Gegend … 0'43 12 12. Choral. Brich an, du schönes Morgenlicht … 1'01 13 13. Rezitativ (Tenor, Sopran [Evangelist, Der Engel]). Und der Engel sprach … 0'42 14 14. Rezitativ (Bass). Was Gott dem Abraham verheißen … 0'39 2 15 15. Arie (Tenor). Frohe Hirten, eilt, ach eilet … 3'35 16 16. Rezitativ (Tenor [Evangelist]). Und das habt zum Zeichen … 0'20 17 17. Choral. Schaut hin! dort liegt im finstern Stall … 0'38 18 18. Rezitativ (Bass). So geht denn hin, ihr Hirten, geht … 0'57 19 19. -

April 27 Cantata Bulletin

Welcome to Grace Lutheran Church We are glad that you have joined us for this afternoon’s Bach Cantata Vespers. For those who have trouble hearing, sound enhancement units are available in the back of the church and may be obtained from an usher. Please silence all cell phones and pagers. Recording or photography of any kind during the service is strictly forbidden. This afternoon’s Bach Cantata Vespers is generously underwritten by the Sukup Family Foundation. 2 The Second Sunday of Easter April 27, 2014 + 3:45 p.m. EVENING PRAYER PRELUDE Fuge, Kanzone, und Epilog (Op. 85, No. 3): Credo in vitam venturi Sigfrid Karg-Elert (1877–1933) Credo in vitam venturi saeculi. Amen. I believe in the life of the world to come. Amen. Steven Wente, organ Paul Christian, violin Prelude to Evening Prayer Richard Hillert (1923–2010) We stand, facing the candle as we sing. SERVICE OF LIGHT 3 4 + PSALMODY + We sit. PSALM 141 Women sing parts marked 1. Men sing parts marked 2. All sing parts marked C. 5 6 Silence for meditation is observed, then: PSALM PRAYER L Let the incense of our repentant prayer ascend before you, O Lord, and let your lovingkindness descend upon us, that with purified minds we may sing your praises with the Church on earth and the whole heavenly host, and may glorify you forever and ever. C Amen. MOTET: Haec dies William Byrd (1540–1623) Haec dies quam fecit Dominus: This is the day that the Lord has made: exultemus et laetemur in ea. Alleluia. let us rejoice and be glad in it. -

Christmas Oratorio

Christmas Oratorio Sunday, December 18, 2011 • 3:00 PM First Free Methodist Church Orchestra Seattle Seattle Chamber Singers Hans-Jürgen Schnoor, conductor Maike Albrecht, soprano • Melissa Plagemann, alto Wesley Rogers, tenor • Steven Tachell, bass JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750) Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248 Chorus: Jauchzet, frohlocket! auf, preiset die Tage Alto: Schlafe, mein Liebster, genieße der Ruh Evangelist: Es begab sich aber zu der Zeit Evangelist: Und alsobald war da bei dem Engel Alto: Nun wird mein liebster Bräutigam Angels: Ehre sei Gott in der Höhe Alto: Bereite dich, Zion, mit zärtlichen Trieben Bass: So recht, ihr Engel, jauchzt und singet Chorale: Wie soll ich dich empfangen Chorale: Wir singen dir in deinem Heer Evangelist: Und sie gebar ihren ersten Sohn Chorale: Er ist auf Erden kommen arm Chorus: Herrscher des Himmels, erhöre das Lallen Bass: Wer will die Liebe recht erhöhn Evangelist: Und da die Engel von ihnen gen Himmel fuhren Bass: Großer Herr, o starker König Shepherds: Lasset uns nun gehen gen Bethlehem Chorale: Ach mein herzliebes Jesulein Bass: Er hat sein Volk getröst’ Chorale: Dies hat er alles uns getan Sinfonia Duet: Herr, dein Mitleid, dein Erbarmen Evangelist: Und es waren Hirten in derselben Gegend Evangelist: Und sie kamen eilend Chorale: Brich an, o schönes Morgenlicht Alto: Schließe, mein Herze, dies selige Wunder Evangelist, Angel: Und der Engel sprach zu ihnen Alto: Ja, ja, mein Herz soll es bewahren Bass: Was Gott dem Abraham verheißen Chorale: Ich will dich mit Fleiß bewahren Tenor: Frohe -

Christmas Oratorio

Conductor’s Notes 1 Conductor’s Notes: Christmas Oratorio © 2010 Ellen Frye Bach’s Christmas Oratorio is a series of six cantatas for the first, second and third days of Christmas, New Year’s Day, Epiphany, and the first Sunday after New Year. The first (and, so far as we know, only) performances of the complete oratorio during Bach’s lifetime were during the 1734–35 Christmas season. The Bach Study Group worked on the Christmas Oratorio from September 2009 through April 2010. The following notes, written for the musicians of that group, focus on the readings I found most interesting. Scripture Bach and his librettist (likely Picander) build the narrative of the Christmas Oratorio around the two gospels—Luke and Matthew— that offer detailed stories of Jesus’ birth. Cantata 1 (Luke 2:1‐7): Joseph and Mary travel to Bethlehem; the child is born in the manger. Cantata 2 (Luke 2:8‐14): The angels announce the birth of Christ to the shepherds. Cantata 3 (Luke 2:15‐20): The shepherds go to Bethlehem and tell what they have witnessed; Mary ponders in her heart. Cantata 4 (Luke 2:21): The child is circumcised and given the name Jesus. Cantata 5 (Matthew 2:1‐6): The Magi ask King Herod for the whereabouts of the new king of the Jews. Cantata 6 (Matthew 2:7–12): The Magi are directed to Bethlehem; they arrive at the manger and then return to their country. Another verse from Luke, the end of the Magnificat (Luke 1:51 “He has performed mighty deeds with his arm; he has scattered those who are proud in their inmost thoughts”), runs through the sixth cantata.