Rev. William Davenant) Three Musical Settings of the Witches’ Scenes in Macbeth Survive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

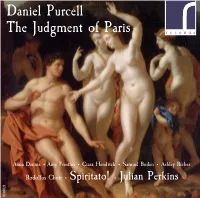

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites

133 The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites Alexander McGrattan Introduction In May 1660 Charles Stuart agreed to Parliament's terms for the restoration of the monarchy and returned to London from exile in France. After eighteen years of political turmoil, which culminated in the puritanical rule of the Commonwealth, Charles II's initial priorities on his accession included re-establishing a suitable social and cultural infrastructure for his court to function. At the outbreak of the civil war in 1642, Parliament had closed the London theatres, and performances of plays were banned throughout the interregnum. In August 1660 Charles issued patents for the establishment of two theatre companies in London. The newly formed companies were patronized by royalty and an aristocracy eager to circulate again in courtly circles. This led to a shift in the focus of theatrical activity from the royal court to the playhouses. The restoration of commercial theatres had a profound effect on the musical life of London. The playhouses provided regular employment to many of its most prominent musicians and attracted others from abroad. During the final quarter of the century, by which time the audiences had come to represent a wider cross-section of London society, they provided a stimulus to the city's burgeoning concert scene. During the Restoration period—in theatrical terms, the half-century following the Restoration of the monarchy—approximately six hundred productions were presented on the London stage. The vast majority of these were spoken dramas, but almost all included a substantial amount of music, both incidental (before the start of the drama and between the acts) and within the acts, and many incorporated masques, or masque-like episodes. -

Theatre of Magic Programme Notes

Theatre of Magic PROGRAMME NOTES The English flocked to the theatres when they were reopened after the Restoration. Old plays by Shakespeare, Beaumont, and Fletcher were reworked and eventually supplemented by works by new playwrights. Music, dance, and spectacle were gradually added to complement the drama. The English had not yet embraced opera as it was understood on the Continent, but the amount of music added to the plays became too significant to ignore, and the English writer Roger North invented the term “semi-opera” to describe these entertainments of “half Musick and half Drama.” The leading parts continued to be spoken by actors, while vocal music was allotted to minor characters, whose contributions were essentially diversions, rarely essential to the action. To this was added instrumental music to accompany dance, set the mood, or accompany scene changes. Our concerts this week open with excerpts from two of these semi-operas, both adaptations of Shakespeare’s magical plays, The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Matthew Locke was arguably England’s leading composer at the time of the Restoration in 1660. He became very active in London’s commercial theatres, contributing music for countless plays. He is best known today for the instrumental music he wrote for The Tempest, produced by Thomas Shadwell in 1674. The text of the semi-opera was adapted by Shadwell from an earlier adaptation (1667) of Shakespeare’s original by John Dryden and William Davenant. Shadwell’s version of the play remained popular for some 75 years. Locke’s opening Curtain Tune is particularly striking: it is a musical depiction of the storm that precedes the play, complete with detailed instructions to the performers (including the instruction to play “Violently” at the height of the storm). -

'Inspire Us Genius of the Day': Rewriting the Regent in the Birthday Ode for Queen Anne, 1703

Eighteenth-Century Music 13/1, 1–21 © Cambridge University Press, 2015 doi:10.1017/S1478570615000421 ‘inspire us genius of the day’: 1 rewriting the regent in the birthday 2 ode for queen anne, 1703 3 estelle murphy 4 ! 5 ABSTRACT 6 In 1701–1702 writer and poet Peter Anthony Motteux collaborated with composer John Eccles, Master of the King’s 7 Musick, in writing the ode for King William III’s birthday. Eccles’s autograph manuscript is listed in the British 8 library manuscript catalogue as ‘Ode for the King’s Birthday, 1703; in score by John Eccles’ and is accompanied 9 by a claim that the ode had already reached folio 10v when William died, requiring the words to be amended to 10 suit his successor, Queen Anne. A closer inspection of this manuscript reveals that much more of the ode had been 11 completed before the king’s death, and that much more than the words ‘king’ and ‘William’ was amended to suit 12 a succeeding monarch of a different gender and nationality. The work was performed before Queen Anne on her 13 birthday in 1703 and the words were published shortly afterwards. Discrepancies between the printed text and 14 that in Eccles’s score indicate that no fewer than three versions of the text were devised during the creative process. 15 These versions raise issues of authority with respect to poet and composer. A careful analysis of the manuscript’s 16 paper types and rastrology reveals a collaborative process of re-engineering that was, in fact, applied to an already 17 completed work. -

An A2 Timeline of the London Stage Between 1660 and 1737

1660-61 1659-60 1661-62 1662-63 1663-64 1664-65 1665-66 1666-67 William Beeston The United Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company @ Salisbury Court Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company & Thomas Killigrew @ Salisbury Court @Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields Sir William Davenant Sir William Davenant Rhodes’s Company @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Red Bull Theatre @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields George Jolly John Rhodes @ Salisbury Court @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane The King’s Company The King’s Company PLAGUE The King’s Company The King’s Company The King’s Company Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew June 1665-October 1666 Anthony Turner Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew Thomas Killigrew @ Vere Street Theatre @ Vere Street Theatre & Edward Shatterell @ Red Bull Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ Bridges Street Theatre @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane @ Bridges Street Theatre, GREAT FIRE @ Red Bull Theatre Drury Lane (from 7/5/1663) The Red Bull Players The Nursery @ The Cockpit, Drury Lane September 1666 @ Red Bull Theatre George Jolly @ Hatton Garden 1676-77 1675-76 1674-75 1673-74 1672-73 1671-72 1670-71 1669-70 1668-69 1667-68 The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company The Duke’s Company Thomas Betterton & William Henry Harrison and Thomas Henry Harrison & Thomas Sir William Davenant Smith for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant Betterton for the Davenant @ Lincoln’s Inn Fields -

Dressing to Delight: the Spectacle of Costume and the Character of the Fop on the Restoration Stage, 1660-1714 Lyndsey Bakewell

DRESSING TO DELIGHT: THE SPECTACLE OF COSTUME AND THE CHARACTER OF THE FOP ON THE RESTORATION STAGE, 1660-1714 Lyndsey Bakewell … for costume and ornament are arrived to the heights of magnificence. —Richard Flecknoe The English Restoration theatre has long been associated with lavish spectacles. This is due in part to developments in scenery and machinery following the return of Charles II and the monarchy in 1660. Drawing influence from European practices experienced by playwrights, players, and audiences while in exile, theatrical practice included an increased technical potential for spectacular visual feats of scenographic and mechanical wonder.1 Contemporary research has often defined the theatrical practices of the Restoration in terms of these advances (see Powell 1984, Hume 1976, and Milhous 1984). When considering the spectacular nature of the English stage in this period, these discussions tend to overlook more traditional elements of stage production, such as costume, acting, and scenography. In contrast, accounts from writers during, and immediately after the Restoration, regularly discuss these elements of production, assuring us of the significance of their contribution to this period’s stage spectaculars. This paper will therefore draw on firsthand accounts and playtexts from the period, as well as reflections on stage practices in the decades that immediately followed the Restoration, in order to broaden notions of what spectacle meant to contemporary audiences and how this was achieved—particularly in relation to costume. By paying close attention to the ways in which clothes were exploited for their portrayal of character and their visual appeal, this paper will demonstrate the spectacular qualities of the seventeenth-century stage. -

PROGRAM NOTES Henry Purcell

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Henry Purcell - Suite from King Arthur Born sometime in 1659, place unknown. Died November 21, 1695, London, England. Suite from King Arthur Purcell composed his semi-opera King Arthur, with texts by John Dryden, in 1691. The first performance was given at the Dorset Garden Theatre in London in May of that year. The orchestra for this suite of instrumental excerpts consists of two oboes and english horn, two trumpets, timpani, and strings, with continuo provided by bassoon and harpsichord. Performance time is approximately twenty minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra has performed music from Purcell's King Arthur (Trumpet Tune, "Ye blust'ring brethren of the skies," with Charles W. Clark as soloist, and Grand Dance: Chaconne) only once previously, on subscription concerts at the Auditorium Theatre on December 13 and 14, 1901, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Henry Purcell is the one composer who lived and worked before J. S. Bach who has found a place in the symphonic repertory. The Chicago Symphony played Purcell's music as early as 1901, when it programmed three selections from King Arthur on the first of its new "historical" programs designed to "illustrate the development of the orchestra and its literature, from the earliest times down to the present day." Purcell still stands at the very beginning of the modern orchestra's repertory, although he is best known to today's audiences for the cameo appearance his music makes in Benjamin Britten's twentieth- century classic, the Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra. Purcell is regularly described as the finest English composer before Edward Elgar, if not as the greatest English composer of all. -

Lully's Psyche (1671) and Locke's Psyche (1675)

LULLY'S PSYCHE (1671) AND LOCKE'S PSYCHE (1675) CONTRASTING NATIONAL APPROACHES TO MUSICAL TRAGEDY IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ' •• by HELEN LLOY WIESE B.A. (Special) The University of Alberta, 1980 B. Mus., The University of Calgary, 1989 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS • in.. • THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF MUSIC We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 1991 © Helen Hoy Wiese, 1991 In presenting this hesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of Kos'iC The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date ~7 Ocf I DE-6 (2/68) ABSTRACT The English semi-opera, Psyche (1675), written by Thomas Shadwell, with music by Matthew Locke, was thought at the time of its performance to be a mere copy of Psyche (1671), a French tragedie-ballet by Moli&re, Pierre Corneille, and Philippe Quinault, with music by Jean- Baptiste Lully. This view, accompanied by a certain attitude that the French version was far superior to the English, continued well into the twentieth century. -

The Protectorate Playhouse: William Davenant's Cockpit in the 1650S

The protectorate playhouse: William Davenant's cockpit in the 1650s Item Type Article Authors Watkins, Stephen Citation Watkins, S. (2019) 'The protectorate playhouse: William Davenant's cockpit in the 1650s', Shakespeare Bulletin, 37(1), pp.89-109. DOI: 10.1353/shb.2019.0004. DOI 10.1353/shb.2019.0004 Publisher John Hopkins University Press Journal Shakespeare Bulletin Download date 30/09/2021 15:44:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/624483 1 The Protectorate Playhouse: William Davenant’s Cockpit in the 1650s STEPHEN WATKINS University of Southampton Recent work on the history of the theater during the decade of republican experiment in England (1649–59) has revealed a modest but sophisticated performance culture, centering on the entrepreneurial and politically wily figure of Sir William Davenant. Despite the ban on stage plays enforced in various forms from 1642, by the mid-1650s Davenant, poet laureate to Charles I and Royalist aid during the civil wars, succeeded in gaining the Protectorate’s approval to produce a series of “Heroick Representations” (Davenant, Proposition 2) for public audiences, first at his private residence of Rutland House and later at the Cockpit theater in Drury Lane. These “Representations” embody a unique corpus in the history of English theater. They were radically innovative productions, introducing the proscenium arch, painted, perspectival scenery, and recitative music to London audiences. The Siege of Rhodes even boasted the first English female performer to appear on a professional public stage. Davenant’s 1650s works were not strictly plays in the usual sense—what John Dryden would later term “just drama” (sig. -

Restoration Keyboard Music

Restoration Keyboard Music This series of concerts is based on my researches into 17th century English keyboard music, especially that of Matthew Locke and his Restoration colleagues, Albertus Bryne and John Roberts. Concert 1. "Melothesia restored". The keyboard music by Matthew Locke and his contemporaries. Given at the David Josefowitz Recital Hall, Royal Academy of Music on Tuesday SEP 30, 2003 Music by Matthew Locke (c.1622-77), Frescobaldi (1583-1643), Chambonnières (c.1602-72), William Gregory (fl 1651-87), Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625), Froberger (1616-67), Albert Bryne (c.1621-c.1670) This programmes sets a selection of Matthew Locke’s remarkable keyboard music within the wider context of seventeenth century keyboard playing. Although Locke confessed little admiration for foreign musical practitioners, he is clearly endebted to European influences. The un-measued prelude style which we find in the Prelude of the final C Major suite, for example, suggest a French influence, perhaps through the lutenists who came to London with the return of Charles II. Locke’s rhythmic notation belies the subtle inflections and nuances of what we might call the international style which he first met as a young man visiting the Netherlands with his future regal employer. One of the greatest keyboard players of his day, Froberger, visited London before 1653 and, not surprisingly, we find his powerful personality behind several pieces in Locke’s pioneering publication, Melothesia. As for other worthy composers of music for the harpsichord and organ, we have Locke's own testimony in his written reply to Thomas Salmon in 1672, where, in addition to Froberger, he mentions Frescobaldi and Chambonnières with the Englishmen John Bull, Orlando Gibbons, Albertus Bryne (his contemporary and organist of Westminster Abbey) and Benjamin Rogers. -

Appendix: Catalogue of Restoration Music Manuscripts Bibliography

Musical Creativity in Restoration England REBECCA HERISSONE Appendix: Catalogue of Restoration Music Manuscripts Bibliography Secondary Sources Ashbee, Andrew, ‘The Transmission of Consort Music in Some Seventeenth-Century English Manuscripts’, in Andrew Ashbee and Peter Holman (eds.), John Jenkins and his Time: Studies in English Consort Music (Oxford: Clarendon, 1996), 243–70. Ashbee, Andrew, Robert Thompson and Jonathan Wainwright, The Viola da Gamba Society Index of Manuscripts Containing Consort Music, 2 vols. (Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate, 2001–8). Bailey, Candace, ‘Keyboard Music in the Hands of Edward Lowe and Richard Goodson I: Oxford, Christ Church Mus. 1176 and Mus. 1177’, Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle, 32 (1999), 119–35. ‘New York Public Library Drexel MS 5611: English Keyboard Music of the Early Restoration’, Fontes artis musicae, 47 (2000), 51–67. Seventeenth-Century British Keyboard Sources, Detroit Studies in Music Bibliography, 83 (Warren: Harmonie Park Press, 2003). ‘William Ellis and the Transmission of Continental Keyboard Music in Restoration England’, Journal of Musicological Research, 20 (2001), 211–42. Banks, Chris, ‘British Library Ms. Mus. 1: A Recently Discovered Manuscript of Keyboard Music by Henry Purcell and Giovanni Battista Draghi’, Brio, 32 (1995), 87–93. Baruch, James Charles, ‘Seventeenth-Century English Vocal Music as reflected in British Library Additional Manuscript 11608’, unpublished PhD dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (1979). Beechey, Gwilym, ‘A New Source of Seventeenth-Century Keyboard Music’, Music & Letters, 50 (1969), 278–89. Bellingham, Bruce, ‘The Musical Circle of Anthony Wood in Oxford during the Commonwealth and Restoration’, Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society of America, 19 (1982), 6–71. -

Age of Dryden Summary

AGE OF DRYDEN SUMMARY John Dryden, (born August 9 [August 19, New Style], 1631, Aldwinkle, Northamptonshire, England—died May 1 [May 12], 1700, London), English poet, dramatist, and literary critic who so dominated the literary scene of his day that it came to be known as the Age of Dryden. The son of a country gentleman, Dryden grew up in the country. When he was 11 years old the Civil War broke out. Both his father’s and mother’s families sided with Parliament against the king, but Dryden’s own sympathies in his youth are unknown. About 1644 Dryden was admitted to Westminster School, where he received a predominantly classical education under the celebrated Richard Busby. His easy and lifelong familiarity with classical literature begun at Westminster later resulted in idiomatic English translations. In 1650 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he took his B.A. degree in 1654. What Dryden did between leaving the university in 1654 and the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 is not known with certainty. In 1659 his contribution to a memorial volume for Oliver Cromwell marked him as a poet worth watching. His “heroic stanzas” were mature, considered, sonorous, and sprinkled with those classical and scientific allusions that characterized his later verse. This kind of public poetry was always one of the things Dryden did best. When in May 1660 Charles II was restored to the throne, Dryden joined the poets of the day in welcoming him, publishing in June Astraea Redux, a poem of more than 300 lines in rhymed couplets.