John Travers: 18 Canzonets for Two and Three Voices (1746) Emanuel Rubin University of Massachusetts - Amherst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

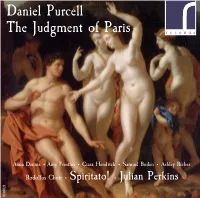

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

The Use of Multiple Stops in Works for Solo Violin by Johann Paul Von

THE USE OF MULTIPLE STOPS IN WORKS FOR SOLO VIOLIN BY JOHANN PAUL VON WESTHOFF (1656-1705) AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO GERMAN POLYPHONIC WRITING FOR A SINGLE INSTRUMENT Beixi Gao, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2017 APPROVED: Julia Bushkova, Major Professor Paul Leenhouts, Committee Member Susan Dubois, Committee Member Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Vice Provost of the Toulouse Graduate School Gao, Beixi. The Use of Multiple Stops in Works for Solo Violin by Johann Paul Von Westhoff (1656-1705) and Its Relationship to German Polyphonic Writing for a Single Instrument. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2017, 32 pp., 19 musical examples, bibliography, 46 titles. Johann Paul von Westhoff's (1656-1705) solo violin works, consisting of Suite pour le violon sans basse continue published in 1683 and Six Suites for Violin Solo in 1696, feature extensive use of multiple stops, which represents a German polyphonic style of the seventeenth- century instrumental music. However, the Six Suites had escaped the public's attention for nearly three hundred years until its rediscovery by the musicologist Peter Várnai in the late twentieth century. This project focuses on polyphonic writing featured in the solo violin works by von Westhoff. In order to fully understand the stylistic traits of this less well-known collection, a brief summary of the composer, Johann Paul Westhoff, and an overview of the historical background of his time is included in this document. -

The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites

133 The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites Alexander McGrattan Introduction In May 1660 Charles Stuart agreed to Parliament's terms for the restoration of the monarchy and returned to London from exile in France. After eighteen years of political turmoil, which culminated in the puritanical rule of the Commonwealth, Charles II's initial priorities on his accession included re-establishing a suitable social and cultural infrastructure for his court to function. At the outbreak of the civil war in 1642, Parliament had closed the London theatres, and performances of plays were banned throughout the interregnum. In August 1660 Charles issued patents for the establishment of two theatre companies in London. The newly formed companies were patronized by royalty and an aristocracy eager to circulate again in courtly circles. This led to a shift in the focus of theatrical activity from the royal court to the playhouses. The restoration of commercial theatres had a profound effect on the musical life of London. The playhouses provided regular employment to many of its most prominent musicians and attracted others from abroad. During the final quarter of the century, by which time the audiences had come to represent a wider cross-section of London society, they provided a stimulus to the city's burgeoning concert scene. During the Restoration period—in theatrical terms, the half-century following the Restoration of the monarchy—approximately six hundred productions were presented on the London stage. The vast majority of these were spoken dramas, but almost all included a substantial amount of music, both incidental (before the start of the drama and between the acts) and within the acts, and many incorporated masques, or masque-like episodes. -

'Inspire Us Genius of the Day': Rewriting the Regent in the Birthday Ode for Queen Anne, 1703

Eighteenth-Century Music 13/1, 1–21 © Cambridge University Press, 2015 doi:10.1017/S1478570615000421 ‘inspire us genius of the day’: 1 rewriting the regent in the birthday 2 ode for queen anne, 1703 3 estelle murphy 4 ! 5 ABSTRACT 6 In 1701–1702 writer and poet Peter Anthony Motteux collaborated with composer John Eccles, Master of the King’s 7 Musick, in writing the ode for King William III’s birthday. Eccles’s autograph manuscript is listed in the British 8 library manuscript catalogue as ‘Ode for the King’s Birthday, 1703; in score by John Eccles’ and is accompanied 9 by a claim that the ode had already reached folio 10v when William died, requiring the words to be amended to 10 suit his successor, Queen Anne. A closer inspection of this manuscript reveals that much more of the ode had been 11 completed before the king’s death, and that much more than the words ‘king’ and ‘William’ was amended to suit 12 a succeeding monarch of a different gender and nationality. The work was performed before Queen Anne on her 13 birthday in 1703 and the words were published shortly afterwards. Discrepancies between the printed text and 14 that in Eccles’s score indicate that no fewer than three versions of the text were devised during the creative process. 15 These versions raise issues of authority with respect to poet and composer. A careful analysis of the manuscript’s 16 paper types and rastrology reveals a collaborative process of re-engineering that was, in fact, applied to an already 17 completed work. -

The Use of Scordatura in Heinrich Biber's Harmonia Artificioso-Ariosa

RICE UNIVERSITY TUE USE OF SCORDATURA IN HEINRICH BIBER'S HARMONIA ARTIFICIOSO-ARIOSA by MARGARET KEHL MITCHELL A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE aÆMl Dr. Anne Schnoebelen, Professor of Music Chairman C<c g>'A. Dr. Paul Cooper, Professor of- Music and Composer in Ldence Professor of Music ABSTRACT The Use of Scordatura in Heinrich Biber*s Harmonia Artificioso-Ariosa by Margaret Kehl Mitchell Violin scordatura, the alteration of the normal g-d'-a'-e" tuning of the instrument, originated from the spirit of musical experimentation in the early seventeenth century. Closely tied to the construction and fittings of the baroque violin, scordatura was used to expand the technical and coloristlc resources of the instrument. Each country used scordatura within its own musical style. Al¬ though scordatura was relatively unappreciated in seventeenth-century Italy, the technique was occasionally used to aid chordal playing. Germany and Austria exploited the technical and coloristlc benefits of scordatura to produce chords, Imitative passages, and special effects. England used scordatura primarily to alter the tone color of the violin, while the technique does not appear to have been used in seventeenth- century France. Scordatura was used for possibly the most effective results in the works of Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber (1644-1704), a virtuoso violin¬ ist and composer. Scordatura appears in three of Biber*s works—the "Mystery Sonatas", Sonatae violino solo, and Harmonia Artificioso- Ariosa—although the technique was used for fundamentally different reasons in each set. In the "Mystery Sonatas", scordatura was used to produce various tone colors and to facilitate certain technical feats. -

John Playford I

JOHN PLAYFORD THE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MUSIC PUBLISHER Part I HOW few, save the musical antiquary, know the name of John Playford or the great debt we owe to him in the matter of seventeenth-century music! There can be but little doubt that but for him the music of that period would have been non-existent to the moderns, except what little had survived the wear and tear of manuscript copies. It was John Playford who, during the troublous and uncertain times of the Commonwealth, when music of a light kind was in disfavour, had the pluck to publish gay songs and pretty dances for the benefit of those whose hearts were not dulled by the Puritanic fanaticism. Had it not been for him music might have fallen stillborn from the brains of the few musicians who composed it. Music publishing had been a dead letter in England for at least a quarter of a century, for after the age of Elizabeth, when in spite of the patents granted to Byrd, Tallis and Morley (who had sole power to print and publish music and a veto over imported music) madrigals were freely published. The musical works published between the death of Elizabeth and the advent of Playford were few indeed. John Playford was born in 1623, died in 1686. If we are to believe the Dictionary of National Biography, he was of a Norfolk family, but of his education we have no knowledge, nor are there in existence any particulars of his early life. And, here to c]ear the ground, let me at once point out certain errors which have been repeated from Sir John Hawkins' History of Music. -

On Common Ground 3: John Playford and the English Dancing Master, 1651 DHDS March 2001 Text Copyright © Jeremy Barlow and DHDS 2001

On Common Ground 3: John Playford and the English Dancing Master, 1651 DHDS March 2001 Text copyright © Jeremy Barlow and DHDS 2001 TUNES IN THE ENGLISH DANCING MASTER, 1651: JOHN PLAYFORD’S ACCIDENTAL MISPRINTS? Jeremy Barlow This conference has given me the opportunity to investigate a theory I began to formu- late twenty years ago, when I compiled my book of the country dance tunes from the 18 editions of The Dancing Master1 . It seemed to me, as I compared variant readings from one edition to another, that John Playford’s original printer, Thomas Harper2 , had lacked certain bits of musical type for the first edition of 16513 (as in all subsequent editions, the music was printed with movable type). In particular it seemed that he lacked the means to indicate high or low notes which required additional stave lines, and that he lacked a sufficient number of sharps4 . I also wondered if this lack of type might not be the principal reason for Play- ford’s claim on the title page of the second edition (1652), that it is ‘Corrected from many grosse Errors which were in the former Edition’. Despite the correction of the notorious misprint reversing the symbols for men and women in the key to the first edition, there are, as the second edition progresses, many more alterations to the tunes than to the dance in- structions. Initially therefore one might conclude that all the musical changes are correc- tions, and that musicians today who fail to take them into account play the tunes wrongly. I hope to demonstrate that the implications of the alterations are far from being clear cut. -

Baroque Recorder Anthology Contents

Saunders Recorders. Schott... Baroque Recorder Anthology Contents Baroque Recorder Anthology - Volume 1. Schott ED 13134 Full Backing Track Track Number Number Title and Composer 01 31 Branle - Jean Hotteterre 02 32 Menuett - Jean Hotteterre 03 33 Mir Hahn en neu Oberkeet - Johann Sebastian Bach 04 34 Boureé - John Blow 05 35 March - Henry Purcell 06 36 Rondeau - Jean-Baptiste Lully 07 Bockxvoetje - Jacob van Eyck 08 Onder de linde groene - Jacob van Eyck 09 36 The British Toper - John Playford 10 38 Rigaudon - Louis Claude Dacquin 11 De zoete zoomer tijden - Jacob van Eyck 12 39 Menuett - George Frideric Handel 13 40 Rigaudon - George Frideric Handel 14 41 Menuet - George Frideric Handel 15 42 Vain Belinda - Anon. 16 43 Don't You Tickle - Anon. 17 44 Country Bumpkin - Anon. 18 45 Fall of the Leafe - Martin Pearson 19 46 Boureé - Johann Fischer 20 Fairy Dance - Anon. Scottish Reel 21 The Gobbie-O - Anon. Scottish Jig 22 47 L'Inconnu - Anon. French 23 48 Contradance - Anon. French 24 49 Gentille - Anon. French 25 50 Masquerade Royale - Roger North 26 51 North's Maggot - Roger North 27 52 Menuet & Trio - James Hook 28 53 Air - Henry Purcell 29 54 Minuet - Jean-Baptiste Lully 30 55 Hornpipe - Henry Purcell All the above tracks are in CD format on the disc provided. (Unaccompanied piecs have no backing track.) Saunders Recorders. Schott... Baroque Recorder Anthology Contents Baroque Recorder Anthology - Volume 2. Schott ED 13135 01... Minuet - Georg Philipp Telemann 02... Rigaudon - Georg Philipp Telemann 03... Passepied - Michel Richard Delalande 04... Trumpet Air - George Bingham 05.. -

Robert Shay (University of Missouri)

Manuscript Culture and the Rebuilding of the London Sacred Establishments, 1660- c.17001 By Robert Shay (University of Missouri) The opportunity to present to you today caused me to reflect on the context in which I began to study English music seriously. As a graduate student in musicology, I found myself in a situation I suspect is rare today, taking courses mostly on Medieval and Renaissance music. I learned to transcribe Notre Dame polyphony, studied modal theory, and edited Italian madrigals, among other pursuits. I had come to musicology with a background in singing and choral conducting, and had grown to appreciate—as a performer—what I sensed were the unique characteristics of English choral music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It was a seminar on the stile antico that finally provided an opportunity to bring together earlier performing and newer research interests. I had sung a few of Henry Purcell’s polyphonic anthems (there really are only a few), liked them a lot, and wondered if they were connected to earlier music by Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, and others, music which I soon came to learn Purcell knew himself. First for the above-mentioned seminar and then for my dissertation, I cast my net broadly, trying to learn as much as I could about Purcell and his connections to earlier English music. I quickly came to discover that the English traditions were, in almost every respect, distinct from the Continental ones I had been studying, ranging from how counterpoint was taught (or not taught) 1 This paper was delivered at a March 2013 symposium at Western Illinois University with the title, “English Cathedral Music and the Persistence of the Manuscript Tradition.” The present version includes some subsequent revisions and a retitling that I felt more accurately described the paper. -

Thomas Young and Eighteenth-Century Tempi Peter Pesic St

Performance Practice Review Volume 18 | Number 1 Article 2 Thomas Young and Eighteenth-Century Tempi Peter Pesic St. John's College, Santa Fe, New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Pesic, Peter (2013) "Thomas Young and Eighteenth-Century Tempi," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 18: No. 1, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.201318.01.02 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol18/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Young and Eighteenth-Century Tempi Dedicated to the memory of Ralph Berkowitz (1910–2011), a great pianist, teacher, and master of tempo. The uthora would like to thank the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation for its support as well as Alexei Pesic for kindly photographing a rare copy of Crotch’s Specimens of Various Styles of Music. This article is available in Performance Practice Review: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol18/iss1/2 Thomas Young and Eighteenth-Century Tempi Peter Pesic In trying to determine musical tempi, we often lack exact and authoritative sources, especially from the eighteenth century, before composers began to indicate metronome markings. Accordingly, any independent accounts are of great value, such as were collected in Ralph Kirkpatrick’s pioneering article (1938) and most recently sur- veyed in this journal by Beverly Jerold (2012).1 This paper brings forward a new source in the writings of the English polymath Thomas Young (1773–1829), which has been overlooked by musicologists because its author’s best-known work was in other fields. -

CDS 4 6 17 with Wendy Week 1.Pages

Amherst Early Music Festival 2017 Central Program Classes Week I Music of England and Spain: Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque Welcome to our exciting Central Program class offerings! Grab a highlighter and take a deep breath! This catalogue includes classes for Week I for students registering for the Central Program. Here’s how to register for classes: 1. Read the catalogue carefully. Classes are listed by period of the day, then by instrument. Pay particular attention to the Classes of General Interest! 2. Select three choices for each period. Occasionally we need to cancel or shift classes, and that’s when your alternate choices are vital to us. By making three choices now, you help make the class sorting process move much more quickly than if we have to call you for your choices.* 3. To fill out a class choice form go to http://www.amherstearlymusic.org/Festival_Classes_combinedform or request a paper form by emailing [email protected]. Fill out the evaluation, giving us as much information about your skills and desires as you can. If filling out a paper form, indicate your 1st, 2nd, and 3rd class choices for each period by copying the class’s sorting codes [in square brackets after the class’s title] onto the Class Choice Form. If you are filling out the form online, you will choose classes by title in the drop- down menu. 4. If you are also attending Week II, please fill out a separate form for Week II classes, using the separate Week II Class Descriptions. If sending paper forms, mail them to us at Amherst Early Music, 35 Webster Street, Nathaniel Allen House, West Newton MA 02465. -

Rev. William Davenant) Three Musical Settings of the Witches’ Scenes in Macbeth Survive

Folger Shakespeare Library Performing Restoration Shakespeare 1. Manuscripts Macbeth (rev. William Davenant) Three musical settings of the witches’ scenes in Macbeth survive. The first, by Matthew Locke, only survives in fragmentary form (see printed sources below). The second, by John Eccles, dates from ca. 1694. The third setting, by Richard Leveridge, dates from ca. 1702 and was performed well into the 19th century. The Folger holds several important sources for the Macbeth music, as noted below. (Charteris 108) W.a.222-227 and W.b.554-564 Partbooks copied ca. 1800 with later additions. Volumes were used in, and probably compiled for, the Oxford University Music Room concerts. Leveridge’s Macbeth music appears in W.a.222-227 and W.b.554-561. (Charteris 115) W.b.529 Copied in the late eighteenth century. The first section consists of miscellaneous pieces, whereas the second section is devoted to Richard Leveridge’s Macbeth, which includes theatrical cues. (Charteris 117) W.b.531 Manuscript score with John Eccles’s Macbeth music. Copied from Lbl. Add. Ms. 12219 by Thomas Oliphant in the mid-nineteenth century. (Charteris 122) W.b.536 Manuscript score with Richard Leveridge’s Macbeth music. Copied in late eighteenth century. (Charteris 123) W.b.537 Manuscript score with Leveridge’s Macbeth music. Copied in the early eighteenth century with later additions. First owner of the manuscript was almost certainly the Drury Lane Theatre. (Charteris 126) W.b.540 Manuscript score with Leveridge’s Macbeth music. Copied in the mid-eighteenth century. (Charteris 131) W.b.548 Manuscript score with Leveridge’s Macbeth music.