John Bowman's Song Performances on the London Stage, 1677-1701 Matthew A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shearer West Phd Thesis Vol 1

THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON (VOL. I) Shearer West A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 1986 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2982 This item is protected by original copyright THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON Ph.D. Thesis St. Andrews University Shearer West VOLUME 1 TEXT In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the I work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. ABSTRACT A theatrical portrait is an image of an actor or actors in character. This genre was widespread in eighteenth century London and was practised by a large number of painters and engravers of all levels of ability. The sources of the genre lay in a number of diverse styles of art, including the court portraits of Lely and Kneller and the fetes galantes of Watteau and Mercier. Three types of media for theatrical portraits were particularly prevalent in London, between ca745 and 1800 : painting, print and book illustration. -

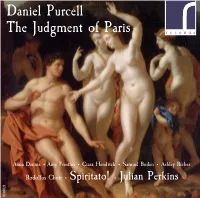

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

1/28/2008 10:56 AM Greetings

1/28/2008 10:56 AM Greetings: This is the last update before we announce the awards on Feb. 15th. If your name is incorrect, or you are in the wrong category, please let us know so we might correct it. If you see someone in a list that does not belong, please share your opinion with us as well. This is a list of your votes, your thoughts, how you feel regarding the music industry in Oklahoma. This list will be opened up to make changes one time before we publish for the final time so before Feb. 14th let us know. On this date we will make final corrections and publish the winners… if all holds together. This year saw many more votes and we are anxious as you to know the final results… Respectfully, Stan Moffat Payne County Line Promotions, LLC Stillwater, OK. 1001 HALL OF FAME: Artist: All American Rejects Bob Childers Cody Canada Cross Canadian Ragweed Don Wood Garth Brooks Johnny Lee Merle Haggard Mike Barham Mike McClure Randy Crouch Ray Wylie Hubbard Scott Evans Stoney LaRue Texas Jack Tom Skinner Travis Linville Wanda Watson Wayne Coyne 1002 HALL OF FAME: Blues Artists: Big Daddy and the Blueskickers D C Miner Dustin Pittsley Jeff Parker Jeff Beguin Kevin Phariss Band Leon Russell The Wanda Watson Band Wanda Watson Wes Jeans Zen Okies 1003 HALL OF FAME: Female Country Artists: Camille Harp Jocelyn Rowland Miss Amy Monica Taylor Reba McEntire Shawna Russell Susan Herndon Wanda Watson 1004 HALL OF FAME: Male Country Artists: Bob Childers Brandon Jenkins Cross Canadian Ragweed Garth Brooks Jason Boland Merle Haggard Mike McClure Randy -

Avant Première Catalogue 2018 Lists UNITEL’S New Productions of 2017 Plus New Additions to the Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première catalogue 2018 lists UNITEL’s new productions of 2017 plus new additions to the catalogue. For a complete list of more than 2.000 UNITEL productions and the Avant Première catalogues of 2015–2017 please visit www.unitel.de FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CATALOGUE 2018 Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany CEO: Jan Mojto Editorial team: Franziska Pascher, Dr. Martina Kliem, Arthur Intelmann Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. Date of Print: February 2018 © UNITEL 2018 All rights reserved Front cover: Alicia Amatriain & Friedemann Vogel in John Cranko’s “Onegin” / Photo: Stuttgart Ballet ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 100TH BIRTHDAY UNITEL CELEBRATES LEONARD BERNSTEIN 1918 – 1990 Leonard Bernstein, a long-time exclusive artist of Unitel, was America’s ambassador to the world of music. -

LCOM182 Lent & Eastertide

LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC Lent, Holy Week, and Eastertide 2018 GRACE CATHEDRAL 2 LITURGICAL CHORAL AND ORGAN MUSIC GRACE CATHEDRAL SAN FRANCISCO LENT, HOLY WEEK, AND EASTERTIDE 2018 11 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LÆTARE Introit: Psalm 32:1-6 – Samuel Wesley Service: Collegium Regale – Herbert Howells Psalm 107 – Thomas Attwood Walmisley O pray for the peace of Jerusalem - Howells Drop, drop, slow tears – Robert Graham Hymns: 686, 489, 473 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Benjamin Bachmann Psalm 107 – Lawrence Thain Canticles: Evening Service in A – Herbert Sumsion Anthem: God so loved the world – John Stainer Hymns: 577, 160 15 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Canticles: Third Service – Philip Moore Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Hymns: 678, 474 18 MARCH 11AM THE HOLY EUCHARIST • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS LENT 5 Introit: Psalm 126 – George M. Garrett Service: Missa Brevis – Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina Psalm 51 – T. Tertius Noble Anthem: Salvator mundi – John Blow Motet: The crown of roses – Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Hymns: 471, 443, 439 3PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CAMERATA Responses: Thomas Tomkins Psalm 51 – Jeffrey Smith Canticles: Short Service – Orlando Gibbons Anthem: Aus tiefer Not – Felix Mendelssohn Hymns: 141, 151 3 22 MARCH 5:15PM CHORAL EVENSONG • CATHEDRAL CHOIR OF MEN AND BOYS Responses: William Byrd Psalm 103 – H. Walford Davies Canticles: Fauxbourdons – Thomas -

Dr. John Blow (1648-1708) Author(S): F

Dr. John Blow (1648-1708) Author(s): F. G. E. Source: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 43, No. 708 (Feb. 1, 1902), pp. 81-88 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3369577 Accessed: 05-12-2015 16:35 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.189.170.231 on Sat, 05 Dec 2015 16:35:56 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE MUSICAL TIMES.-FEBRUARY I, 1902. 81 THE MUSICAL composerof some fineanthems and known to TIMES everybodyas the authorof the ' Grand chant,'- AND SINGING-CLASS CIRCULAR. and William Turner. These three boys FEBRUARY I, 1902. collaboratedin the productionof an anthem, therebycalled the Club Anthem,a settingof the words ' I will always give thanks,'each young gentlemanbeing responsible for one of its three DR. JOHN BLOW movements. The origin of this anthem is variouslystated; but the juvenile joint pro- (1648-I7O8). -

The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites

133 The Trumpet in Restoration Theatre Suites Alexander McGrattan Introduction In May 1660 Charles Stuart agreed to Parliament's terms for the restoration of the monarchy and returned to London from exile in France. After eighteen years of political turmoil, which culminated in the puritanical rule of the Commonwealth, Charles II's initial priorities on his accession included re-establishing a suitable social and cultural infrastructure for his court to function. At the outbreak of the civil war in 1642, Parliament had closed the London theatres, and performances of plays were banned throughout the interregnum. In August 1660 Charles issued patents for the establishment of two theatre companies in London. The newly formed companies were patronized by royalty and an aristocracy eager to circulate again in courtly circles. This led to a shift in the focus of theatrical activity from the royal court to the playhouses. The restoration of commercial theatres had a profound effect on the musical life of London. The playhouses provided regular employment to many of its most prominent musicians and attracted others from abroad. During the final quarter of the century, by which time the audiences had come to represent a wider cross-section of London society, they provided a stimulus to the city's burgeoning concert scene. During the Restoration period—in theatrical terms, the half-century following the Restoration of the monarchy—approximately six hundred productions were presented on the London stage. The vast majority of these were spoken dramas, but almost all included a substantial amount of music, both incidental (before the start of the drama and between the acts) and within the acts, and many incorporated masques, or masque-like episodes. -

Season of 1703-04 (Including the Summer Season of 1704), the Drury Lane Company Mounted 64 Mainpieces and One Medley on a Total of 177 Nights

Season of 1703-1704 n the surface, this was a very quiet season. Tugging and hauling occur- O red behind the scenes, but the two companies coexisted quite politely for most of the year until a sour prologue exchange occurred in July. Our records for Drury Lane are virtually complete. They are much less so for Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which advertised almost not at all until 18 January 1704. At that time someone clearly made a decision to emulate Drury Lane’s policy of ad- vertising in London’s one daily paper. Neither this season nor the next did the LIF/Queen’s company advertise every day, but the ads become regular enough that we start to get a reasonable idea of their repertory. Both com- panies apparently permitted a lot of actor benefits during the autumn—pro- bably a sign of scanty receipts and short-paid salaries. Throughout the season advertisements make plain that both companies relied heavily on entr’acte song and dance to pull in an audience. Newspaper bills almost always mention singing and dancing, sometimes specifying the items in considerable detail, whereas casts are never advertised. Occasionally one or two performers will be featured, but at this date the cast seems not to have been conceived as the basic draw. Or perhaps the managers were merely economizing, treating newspaper advertisements as the equivalent of handbills rather than “Great Bills.” The importance of music to the public at this time is also evident in the numerous concerts of various sorts on offer, and in the founding of The Monthly Mask of Vocal Musick, a periodical devoted to printing new songs, including some from the theatre.1 One of the most interesting developments of this season is a ten-concert series generally advertised as “The Subscription Musick.” So far as we are aware, it has attracted no scholarly commentary whatever, but it may well be the first series of its kind in the history of music in London. -

Reguły Przekładu. Wieczorna Ulewa Hiroshige I Japonaiserie, Pont Sous Lapluie Van Gogha

REGUŁY PRZEKŁADU. WIECZORNA ULEWA HIROSHIGE I JAPONAISERIE, PONT SOUS LAPLUIE VAN GOGHA Mój drogi bracie, wiesz, że wyjechałem na południe i zacząłem tu pra cować dla tysiąca powodów. Chciałem widzieć inne światło, myślałem, że przyroda pod czystym niebem może mi dać właściwsze wyobrażenie o sposobie odczuwania Japończyków i o ich rysunku. Chciałem w końcu widzieć silniej świecące słońce, ponieważ nie widząc go nie sposób zrozu mieć, w sensie wykonania, techniki obrazów Delacroix, a także dlatego, że kolory widma słonecznego są na północy spowite w mgłę1. JAPONAISERIE FOR EVER Nie jest możliwe określenie daty wyznaczającej początek zaintereso wań van Gogha sztuką japońską. Orton przytacza list z 1884 roku napi sany przez artystę do jego przyjaciela wyjeżdżającego do holenderskich Indii Wschodnich, wskazujący na znajomość i uznanie dla wyrobów ja pońskich2. Van Gogh mógł zapoznać się z nimi podczas swego drugiego pobytu w Hadze, od grudnia 1881 do września 1883, kiedy drzeworyty ja pońskie były w ciągłej sprzedaży m.in. w Wielkim Bazarze Królewskim na Zeestraat3, zwłaszcza że od czasów londyńskich zaczyna się okres jego intensywnych poszukiwań twórczych, których skala sięga od Akademii 1 List 605 do Theo z 10 września 1889. V. van G ogh, Listy do brata, Warszawa 1964, s. 540. Numeracja listów wg: The Complete Letters o f Vincent Van Gogh, vol. 3, New York n.d. (1957). 2 Większość faktów dotyczących praktycznych związków van Gogha ze sztuką japońską zaczerpnąłem z eseju Willema van Gulika i Freda Ortona w katalogu kolekcji japoń skiej van Gogha: Japanese Prints collected by Vincent van Gogh, Amsterdam 1978, s. 14-23. 3 Kolekcja von Siebolda, pierwsza w Europie profesjonalna ekspozycja obiektów pocho dzących z Japonii, w tym drzeworytów, otwarta została dla publiczności w Leiden w 1837. -

The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh

THE LETTERS OF VINCENT VAN GOGH ‘Van Gogh’s letters… are one of the greatest joys of modern literature, not only for the inherent beauty of the prose and the sharpness of the observations but also for their portrait of the artist as a man wholly and selessly devoted to the work he had to set himself to’ - Washington Post ‘Fascinating… letter after letter sizzles with colorful, exacting descriptions … This absorbing collection elaborates yet another side of this beuiling and brilliant artist’ - The New York Times Book Review ‘Ronald de Leeuw’s magnicent achievement here is to make the letters accessible in English to general readers rather than art historians, in a new translation so excellent I found myself reading even the well-known letters as if for the rst time… It will be surprising if a more impressive volume of letters appears this year’ — Observer ‘Any selection of Van Gogh’s letters is bound to be full of marvellous things, and this is no exception’ — Sunday Telegraph ‘With this new translation of Van Gogh’s letters, his literary brilliance and his statement of what amounts to prophetic art theories will remain as a force in literary and art history’ — Philadelphia Inquirer ‘De Leeuw’s collection is likely to remain the denitive volume for many years, both for the excellent selection and for the accurate translation’ - The Times Literary Supplement ‘Vincent’s letters are a journal, a meditative autobiography… You are able to take in Vincent’s extraordinary literary qualities … Unputdownable’ - Daily Telegraph ABOUT THE AUTHOR, EDITOR AND TRANSLATOR VINCENT WILLEM VAN GOGH was born in Holland in 1853. -

Jane Milling

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘“For Without Vanity I’m Better Known”: Restoration Actors and Metatheatre on the London Stage.’ AUTHORS Milling, Jane JOURNAL Theatre Survey DEPOSITED IN ORE 18 March 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/4491 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Theatre Survey 52:1 (May 2011) # American Society for Theatre Research 2011 doi:10.1017/S0040557411000068 Jane Milling “FOR WITHOUT VANITY,I’M BETTER KNOWN”: RESTORATION ACTORS AND METATHEATRE ON THE LONDON STAGE Prologue, To the Duke of Lerma, Spoken by Mrs. Ellen[Nell], and Mrs. Nepp. NEPP: How, Mrs. Ellen, not dress’d yet, and all the Play ready to begin? EL[LEN]: Not so near ready to begin as you think for. NEPP: Why, what’s the matter? ELLEN: The Poet, and the Company are wrangling within. NEPP: About what? ELLEN: A prologue. NEPP: Why, Is’t an ill one? NELL[ELLEN]: Two to one, but it had been so if he had writ any; but the Conscious Poet with much modesty, and very Civilly and Sillily—has writ none.... NEPP: What shall we do then? ’Slife let’s be bold, And speak a Prologue— NELL[ELLEN]: —No, no let us Scold.1 When Samuel Pepys heard Nell Gwyn2 and Elizabeth Knipp3 deliver the prologue to Robert Howard’s The Duke of Lerma, he recorded the experience in his diary: “Knepp and Nell spoke the prologue most excellently, especially Knepp, who spoke beyond any creature I ever heard.”4 By 20 February 1668, when Pepys noted his thoughts, he had known Knipp personally for two years, much to the chagrin of his wife.