Intestinal Immune Homeostasis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERK Antibody / EIF2AK3 (RQ4206)

PERK Antibody / EIF2AK3 (RQ4206) Catalog No. Formulation Size RQ4206 0.5mg/ml if reconstituted with 0.2ml sterile DI water 100 ug Bulk quote request Availability 1-3 business days Species Reactivity Human, Mouse, Rat Format Antigen affinity purified Clonality Polyclonal (rabbit origin) Isotype Rabbit IgG Purity Antigen affinity purified Buffer Lyophilized from 1X PBS with 2% Trehalose and 0.025% sodium azide UniProt Q9NZJ5 Applications Western Blot : 0.5-1ug/ml Flow cytometry : 1-3ug/10^6 cells Direct ELISA : 0.1-0.5ug/ml Limitations This PERK antibody is available for research use only. Western blot testing of human 1) HeLa, 2) COLO320, 3) A549, 4) SK-OV-3, 5) A431, 6) rat brain and 7) mouse brain lysate with PERK antibody at 0.5ug/ml. Predicted molecular weight ~125 kDa, observed here at ~140 kDa. Flow cytometry testing of human HepG2 cells with PERK antibody at 1ug/10^6 cells (blocked with goat sera); Red=cells alone, Green=isotype control, Blue= PERK antibody. Description Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 3, also known as protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the EIF2AK3 gene. The protein encoded by this gene phosphorylates the alpha subunit of eukaryotic translation-initiation factor 2, leading to its inactivation, and thus to a rapid reduction of translational initiation and repression of global protein synthesis. This protein is thought to modulate mitochondrial function. It is a type I membrane protein located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it is induced by ER stress caused by malfolded proteins. -

De Novo EIF2AK1 and EIF2AK2 Variants Are Associated with Developmental Delay, Leukoencephalopathy, and Neurologic Decompensation

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/757039; this version posted September 16, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. De novo EIF2AK1 and EIF2AK2 variants are associated with developmental delay, leukoencephalopathy, and neurologic decompensation Dongxue Mao1,2, Chloe M. Reuter3,4, Maura R.Z. Ruzhnikov5,6, Anita E. Beck7, Emily G. Farrow8,9,10, Lisa T. Emrick1,11,12,13, Jill A. Rosenfeld12, Katherine M. Mackenzie5, Laurie Robak2,12,13, Matthew T. Wheeler3,14, Lindsay C. Burrage12,13, Mahim Jain15, Pengfei Liu12, Daniel Calame11,13, Sebastien Küry17,18, Martin Sillesen19, Klaus Schmitz-Abe20, Davide Tonduti21, Luigina Spaccini22, Maria Iascone23, Casie A. Genetti20, Madeline Graf16, Alyssa Tran12, Mercedes Alejandro12, Undiagnosed Diseases Network, Brendan H. Lee12,13, Isabelle Thiffault8,9,24, Pankaj B. Agrawal#,20, Jonathan A. Bernstein#,3,25, Hugo J. Bellen#,2,12,26,27,28, Hsiao- Tuan Chao#,1,2,11,12,13,28,27,29 #Correspondence should be addressed: [email protected] (P.A.), [email protected] (J.A.B.), [email protected] (H.J.B.), [email protected] (H.T.C.) 1Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine (BCM), Houston, TX 2Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX 3Stanford Center for Undiagnosed Diseases, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 4Stanford Center for Inherited Cardiovascular Disease, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, -

Table S1. Complete Gene List. Genbank Refseq and Description of Each Gene Were Provided By

Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 24/09/2021. This copy is for personal use. Any transmission of this document by any media or format is strictly prohibited. Table S1. Complete gene list. GenBank RefSeq and description of each gene were provided by the array supplier. Unigene GeneBank Symbol Description Gene Name/s Rn.11422 NM_033230 Akt1 V-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 Akt Rn.2104 NM_019288 App Amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein - Rn.23323 NM_001034933 Arsa Arylsulfatase A MGC125207 Rn.94004 NM_033443 Arsb Arylsulfatase B - Rn.6224 NM_001038495 Atg12 ATG12 autophagy related 12 Apg12l, MGC125080 Rn.101734NM_001108809 Atg16l1 ATG16 autophagy related 16-like 1 Apg16l, Wdr30 Rn.104199NM_001191560 Atg16l2 ATG16 autophagy related 16-like 2 RGD1311400 Rn.3084 NM_134394 Atg3 ATG3 autophagy related 3 Apg3l, PIG-1, Pig1 Rn.163086NM_001025711 Atg4b ATG4 autophagy related 4 homolog B Apg4b, MGC112887 Rn.23378 NM_001107948 Atg4c ATG4 autophagy related 4 homolog C - Rn.98385 NM_001014250 Atg5 ATG5 autophagy related 5 - Rn.162765NM_001012097 Atg7 ATG7 autophagy related 7 Apg7l Rn.35248 NM_001014218 Atg9a ATG9 autophagy related 9 homolog A MGC105908, RGD1310450 Rn.36696 NM_022698 Bad BCL2-associated agonist of cell death MGC72439 Rn.14598 NM_053812 Bak1 BCL2-antagonist/killer 1 MGC108627 Rn.10668 NM_017059 Bax Bcl2-associated X protein - Rn.9996 NM_016993 Bcl2 B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 Bcl-2 Rn.10323 NM_031535 Bcl2l1 Bcl2-like 1 Bcl-xl, Bcl2l, Bclx, bcl-X Rn.2776 NM_053739 Becn1 Beclin 1, autophagy related - Rn.31142 NM_022684 -

LIM and Cysteine-Rich Domains 1 (LMCD1) Regulates Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy, Calcium Handling, and Force Duarte M

Ferreira et al. Skeletal Muscle (2019) 9:26 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13395-019-0214-1 RESEARCH Open Access LIM and cysteine-rich domains 1 (LMCD1) regulates skeletal muscle hypertrophy, calcium handling, and force Duarte M. S. Ferreira1, Arthur J. Cheng2,3, Leandro Z. Agudelo1,4, Igor Cervenka1, Thomas Chaillou2,5, Jorge C. Correia1, Margareta Porsmyr-Palmertz1, Manizheh Izadi1,6, Alicia Hansson1, Vicente Martínez-Redondo1, Paula Valente-Silva1, Amanda T. Pettersson-Klein1, Jennifer L. Estall7, Matthew M. Robinson8, K. Sreekumaran Nair8, Johanna T. Lanner2 and Jorge L. Ruas1* Abstract Background: Skeletal muscle mass and strength are crucial determinants of health. Muscle mass loss is associated with weakness, fatigue, and insulin resistance. In fact, it is predicted that controlling muscle atrophy can reduce morbidity and mortality associated with diseases such as cancer cachexia and sarcopenia. Methods: We analyzed gene expression data from muscle of mice or human patients with diverse muscle pathologies and identified LMCD1 as a gene strongly associated with skeletal muscle function. We transiently expressed or silenced LMCD1 in mouse gastrocnemius muscle or in mouse primary muscle cells and determined muscle/cell size, targeted gene expression, kinase activity with kinase arrays, protein immunoblotting, and protein synthesis levels. To evaluate force, calcium handling, and fatigue, we transduced the flexor digitorum brevis muscle with a LMCD1-expressing adenovirus and measured specific force and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release in individual fibers. Finally, to explore the relationship between LMCD1 and calcineurin, we ectopically expressed Lmcd1 in the gastrocnemius muscle and treated those mice with cyclosporine A (calcineurin inhibitor). In addition, we used a luciferase reporter construct containing the myoregulin gene promoter to confirm the role of a LMCD1- calcineurin-myoregulin axis in skeletal muscle mass control and calcium handling. -

Biomarkers, Master Regulators and Genomic Fabric Remodeling in a Case of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Biomarkers, Master Regulators and Genomic Fabric Remodeling in a Case of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Dumitru A. Iacobas Personalized Genomics Laboratory, CRI Center for Computational Systems Biology, Roy G Perry College of Engineering, Prairie View A&M University, Prairie View, TX 77446, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-936-261-9926 Received: 1 August 2020; Accepted: 1 September 2020; Published: 2 September 2020 Abstract: Publicly available (own) transcriptomic data have been analyzed to quantify the alteration in functional pathways in thyroid cancer, establish the gene hierarchy, identify potential gene targets and predict the effects of their manipulation. The expression data have been generated by profiling one case of papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) and genetically manipulated BCPAP (papillary) and 8505C (anaplastic) human thyroid cancer cell lines. The study used the genomic fabric paradigm that considers the transcriptome as a multi-dimensional mathematical object based on the three independent characteristics that can be derived for each gene from the expression data. We found remarkable remodeling of the thyroid hormone synthesis, cell cycle, oxidative phosphorylation and apoptosis pathways. Serine peptidase inhibitor, Kunitz type, 2 (SPINT2) was identified as the Gene Master Regulator of the investigated PTC. The substantial increase in the expression synergism of SPINT2 with apoptosis genes in the cancer nodule with respect to the surrounding normal tissue (NOR) suggests that SPINT2 experimental overexpression may force the PTC cells into apoptosis with a negligible effect on the NOR cells. The predictive value of the expression coordination for the expression regulation was validated with data from 8505C and BCPAP cell lines before and after lentiviral transfection with DDX19B. -

S41598-018-20541-8.Pdf

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Ormeloxifene-induced unfolded protein response contributes to autophagy-associated apoptosis Received: 28 September 2016 Accepted: 19 January 2018 via disruption of Akt/mTOR and Published: xx xx xxxx activation of JNK Arindam Bhattacharjee1, Mohammad Hasanain2, Manoj Kathuria1, Akhilesh Singh2, Dipak Datta2,3, Jayanta Sarkar2,3 & Kalyan Mitra1,3 Autophagy, a regulated nutrient recycling program can afect both cell survival and cell death. Here, we show that Ormeloxifene (ORM), a selective estrogen receptor modulator approved for oral contraceptive use induces autophagic fux in ovarian cancer cells, which is activated by an ER stress response upstream of autophagy. The ER stress response is characterized by activation of IRE1α, PERK and ATF6 and is under regulation of JNK. Pharmacological inhibition of either autophagy or ER stress increased cell survival, as did silencing of autophagy proteins LC3 and Beclin 1, implying that ORM-induced autophagy is pro-death in nature. Ultrastructural observations of treated cells confrmed stages of autophagic maturation. Caspase-dependent apoptosis succeeded these events and was characterized by generation of reactive oxygen species and disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential. A concomitant inhibition of the Akt/mTOR axis was also observed with possible regulation of Akt by ORM. ORM inhibited tumor growth in ovarian xenograft model and displayed autophagic activity. In summary, in vitro and in vivo results reveal that ORM induces autophagy-associated cell death to attenuate proliferation of ovarian cancer cells. Our results demonstrate that using ORM in combination with ER stress and autophagy modulators could ofer better therapeutic outcome in ovarian cancer. Ovarian cancer is one of the leading gynecological malignancies among women in terms of mortality1. -

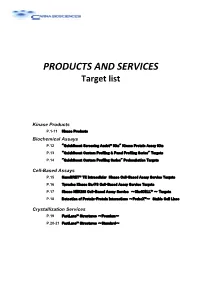

PRODUCTS and SERVICES Target List

PRODUCTS AND SERVICES Target list Kinase Products P.1-11 Kinase Products Biochemical Assays P.12 "QuickScout Screening Assist™ Kits" Kinase Protein Assay Kits P.13 "QuickScout Custom Profiling & Panel Profiling Series" Targets P.14 "QuickScout Custom Profiling Series" Preincubation Targets Cell-Based Assays P.15 NanoBRET™ TE Intracellular Kinase Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.16 Tyrosine Kinase Ba/F3 Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.17 Kinase HEK293 Cell-Based Assay Service ~ClariCELL™ ~ Targets P.18 Detection of Protein-Protein Interactions ~ProbeX™~ Stable Cell Lines Crystallization Services P.19 FastLane™ Structures ~Premium~ P.20-21 FastLane™ Structures ~Standard~ Kinase Products For details of products, please see "PRODUCTS AND SERVICES" on page 1~3. Tyrosine Kinases Note: Please contact us for availability or further information. Information may be changed without notice. Expression Protein Kinase Tag Carna Product Name Catalog No. Construct Sequence Accession Number Tag Location System HIS ABL(ABL1) 08-001 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1) 08-401-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [E255K] HIS ABL(ABL1)[E255K] 08-094 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) HIS ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-093 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [T315I] BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-493-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ACK(TNK2) GST ACK(TNK2) 08-196 Catalytic domain -

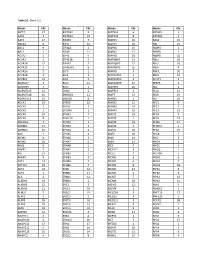

Table S1. Gene List Genes Chr Genes Chr Genes Chr Genes Chr SEPT9

Table S1. Gene List Genes Chr Genes Chr Genes Chr Genes Chr SEPT9 17 EIF2AK3 2 MAPK14 6 RASSF5 1 AAK1 2 EIF2AK4 15 MAPK15 8 RAVER2 1 AATK 17 EIF2B5 3 MAPK3 16 RAX2 19 ABCA1 9 EIF3J 15 MAPK4 18 RB1 13 ABL1 9 EIF4A2 3 MAPK6 15 RBBP4 1 ABL2 1 EIF4B 12 MAPK7 17 RBBP5 1 ACTR2 2 EIF4E 4 MAPK8 10 RBBP8 18 ACVR1 2 EIF4E1B 5 MAPK8IP1 11 RBL1 20 ACVR1B 12 EIF4E2 2 MAPK8IP2 22 RBL2 16 ACVR1C 2 EIF4EBP1 8 MAPK8IP3 16 RBPJ 4 ACVR2A 2 ELF3 1 MAPK9 5 RBPJL 20 ACVR2B 3 ELF4 X MAPKAPK2 1 RBX1 22 ACVRL1 12 ELK1 X MAPKAPK3 3 RCHY1 4 ADAM17 2 ELK3 12 MAPKAPK5 12 REEP5 5 ADAM29 4 ELK4 1 MAPRE1 20 REL 2 ADAMTS15 11 EML4 2 MAPRE3 2 RELA 11 ADAMTS18 16 ENDOD1 11 MAPT 17 RELB 19 ADAMTSL3 15 ENDOG 9 MARK1 1 RET 10 ADCK1 14 EP300 22 MARK2 11 RFC1 4 ADCK2 7 EPAS1 2 MARK3 14 RFC2 7 ADCK3 1 EPCAM 2 MARK4 19 RFC3 13 ADCK4 19 EPHA1 7 MAST1 19 RFC4 3 ADCK5 8 EPHA10 1 MAST2 1 RFC5 12 ADORA1 1 EPHA2 1 MAST3 19 RFNG 17 ADRBK1 11 EPHA3 3 MAST4 5 RFWD2 1 ADRBK2 22 EPHA4 2 MASTL 10 RFX2 19 AGK 7 EPHA5 4 MATK 19 RHEB 7 AIFM1 X EPHA6 3 MAX 14 RHO 3 AIFM2 10 EPHA7 6 MBIP 14 RHOA 3 AIM1 6 EPHA8 1 MCC 5 RHOC 1 AIMP2 7 EPHB1 3 MCF2L2 3 RHOQ 2 AIP 11 EPHB2 1 MCL1 1 RICTOR 5 AKAP4 X EPHB3 3 MCM2 3 RIOK1 6 AKT1 14 EPHB4 7 MCM3 6 RIOK2 5 AKT1S1 19 EPHB6 7 MCM4 8 RIOK3 18 AKT2 19 EPS8 12 MCM5 22 RIPK1 6 AKT3 1 ERBB2 17 MCM6 2 RIPK2 8 ALK 2 ERBB3 12 MCM7 7 RIPK3 14 ALKBH1 14 ERBB4 2 MCM8 20 RIPK4 21 ALKBH2 12 ERC2 3 MDM2 12 RMI1 9 ALKBH3 11 ERCC1 19 MDM4 1 RNASEL 1 ALMS1 2 ERCC2 19 MECOM 3 RNF213 17 ALPK1 4 ERCC3 2 MED12 X RNF220 1 ALPK2 18 ERCC4 16 MED12L 3 ROCK1 18 ALPK3 15 ERCC5 13 -

Tyrosine Phosphorylation: from Discovery to the Kinome and Beyond

The 2007 Herbert Tabor - Journal of Biological Chemistry Lecture Tony Hunter Tyrosine phosphorylation: from discovery to the kinome and beyond ASBMB Annual Meeting April 28, 2007 So far 43 JBC papers and one submitted! The History of Protein Phosphorylation Protein kinase ATP ADP Protein P.Protein P Protein phosphatase The History of Protein Phosphorylation Phospho- Protein Phospho- Src serine in kinase tyrosine tyrosine proteins activity in fly eggs kinase 1932 1954 1964 1979 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Phospho Phospho- Phosph- cAMP Gleevec -protein tyrosine orylase depen- approved discovery synthesis kinase dent PK for CML 1906 1933 1959 1968 2001 The History of Protein Phosphorylation J. Biol. Chem. 2:127 (1906) Phospho- Protein Phospho- Src serine in kinase tyrosine tyrosine proteins activity in fly eggs kinase 1932 1954 1964 1979 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Phospho Phospho- Phosph- cAMP Gleevec -protein tyrosine orylase depen- approved discovery synthesis kinase dent PK for CML 1906 1933 1959 1968 2001 The History of Protein Phosphorylation J. Biol. Chem. 98:109 (1932) Phospho- Protein Phospho- Src serine in kinase tyrosine tyrosine proteins activity in fly eggs kinase 1932 1954 1964 1979 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Phospho Phospho- Phosph- cAMP Gleevec -protein tyrosine orylase depen- approved discovery synthesis kinase dent PK for CML 1906 1933 1959 1968 2001 The History of Protein Phosphorylation J. Biol. Chem. 100:583 (1933) Phospho- Protein Phospho- Src serine in kinase tyrosine tyrosine proteins activity in fly eggs kinase 1932 1954 1964 1979 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Phospho Phospho- Phosph- cAMP Gleevec -protein tyrosine orylase depen- approved discovery synthesis kinase dent PK for CML 1906 1933 1959 1968 2001 The History of Protein Phosphorylation J. -

Page 1 Exploring the Understudied Human Kinome For

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.02.022277; this version posted June 30, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Exploring the understudied human kinome for research and therapeutic opportunities Nienke Moret1,2,*, Changchang Liu1,2,*, Benjamin M. Gyori2, John A. Bachman,2, Albert Steppi2, Rahil Taujale3, Liang-Chin Huang3, Clemens Hug2, Matt Berginski1,4,5, Shawn Gomez1,4,5, Natarajan Kannan,1,3 and Peter K. Sorger1,2,† *These authors contributed equally † Corresponding author 1The NIH Understudied Kinome Consortium 2Laboratory of Systems Pharmacology, Department of Systems Biology, Harvard Program in Therapeutic Science, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA 3 Institute of Bioinformatics, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, 30602 USA 4 Department of Pharmacology, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA 5 Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA Key Words: kinase, human kinome, kinase inhibitors, drug discovery, cancer, cheminformatics, † Peter Sorger Warren Alpert 432 200 Longwood Avenue Harvard Medical School, Boston MA 02115 [email protected] cc: [email protected] 617-432-6901 ORCID Numbers Peter K. Sorger 0000-0002-3364-1838 Nienke Moret 0000-0001-6038-6863 Changchang Liu 0000-0003-4594-4577 Ben Gyori 0000-0001-9439-5346 John Bachman 0000-0001-6095-2466 Albert Steppi 0000-0001-5871-6245 Page 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.02.022277; this version posted June 30, 2020. -

Characterization of a Novel PERK Kinase Inhibitor with Antitumor and Anti-Angiogenic Activity

Published OnlineFirst January 18, 2013; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3109 Cancer Tumor and Stem Cell Biology Research Characterization of a Novel PERK Kinase Inhibitor with Antitumor and Anti-Angiogenic Activity Charity Atkins1, Qi Liu1, Elisabeth Minthorn1, Shu-Yun Zhang1, David J. Figueroa1, Katherine Moss1, Thomas B. Stanley3, Brent Sanders1, Aaron Goetz2, Nathan Gaul2, Anthony E. Choudhry2, Hasan Alsaid4, Beat M. Jucker4, Jeffrey M. Axten1, and Rakesh Kumar1 Abstract The unfolded protein response (UPR) is a signal transduction pathway that coordinates cellular adaptation to microenvironmental stresses that include hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, and change in redox status. These stress stimuli are common in many tumors and thus targeting components of the UPR signaling is an attractive therapeutic approach. We have identified a first-in-class, small molecule inhibitor of the eukaryotic initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 3 (EIF2AK3) or PERK, one of the three mediators of UPR signaling. GSK2656157 is an ATP-competitive inhibitor of PERK enzyme activity with an IC50 of 0.9 nmol/L. It is highly selective for PERK with IC50 values >100 nmol/L against a panel of 300 kinases. GSK2656157 inhibits PERK activity in cells – with an IC50 in the range of 10 30 nmol/L as shown by inhibition of stress-induced PERK autophosphorylation, eIF2a substrate phosphorylation, together with corresponding decreases in ATF4 and CAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) in multiple cell lines. Oral administration of GSK2656157 to mice shows a dose- and time-dependent pharmacodynamic response in pancreas as measured by PERK autophosphoryla- tion. Twice daily dosing of GSK2656157 results in dose-dependent inhibition of multiple human tumor xenografts growth in mice. -

Discovery and Characterization of Novel Inhibitors of Protein Kinase R

Discovery and Characterization of Novel Inhibitors of Protein Kinase R by Unkyung Shin Department of Biochemistry McGill University, Montreal August 2013 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Science Unkyung Shin 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................. v ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................... vi RÉ SUMÉ ............................................................................................................. vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................. viii PREFACE ............................................................................................................. ix CONTRIBUTION OF AUTHORS ..................................................................... x ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION TO KNOWLEDGE ....................................... xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 12 1.1 Protein Synthesis ......................................................................................... 12 1.2 Eukaryotic Translation Initiation ................................................................ 13 1.2.1 Cap-dependent initiation......................................................................