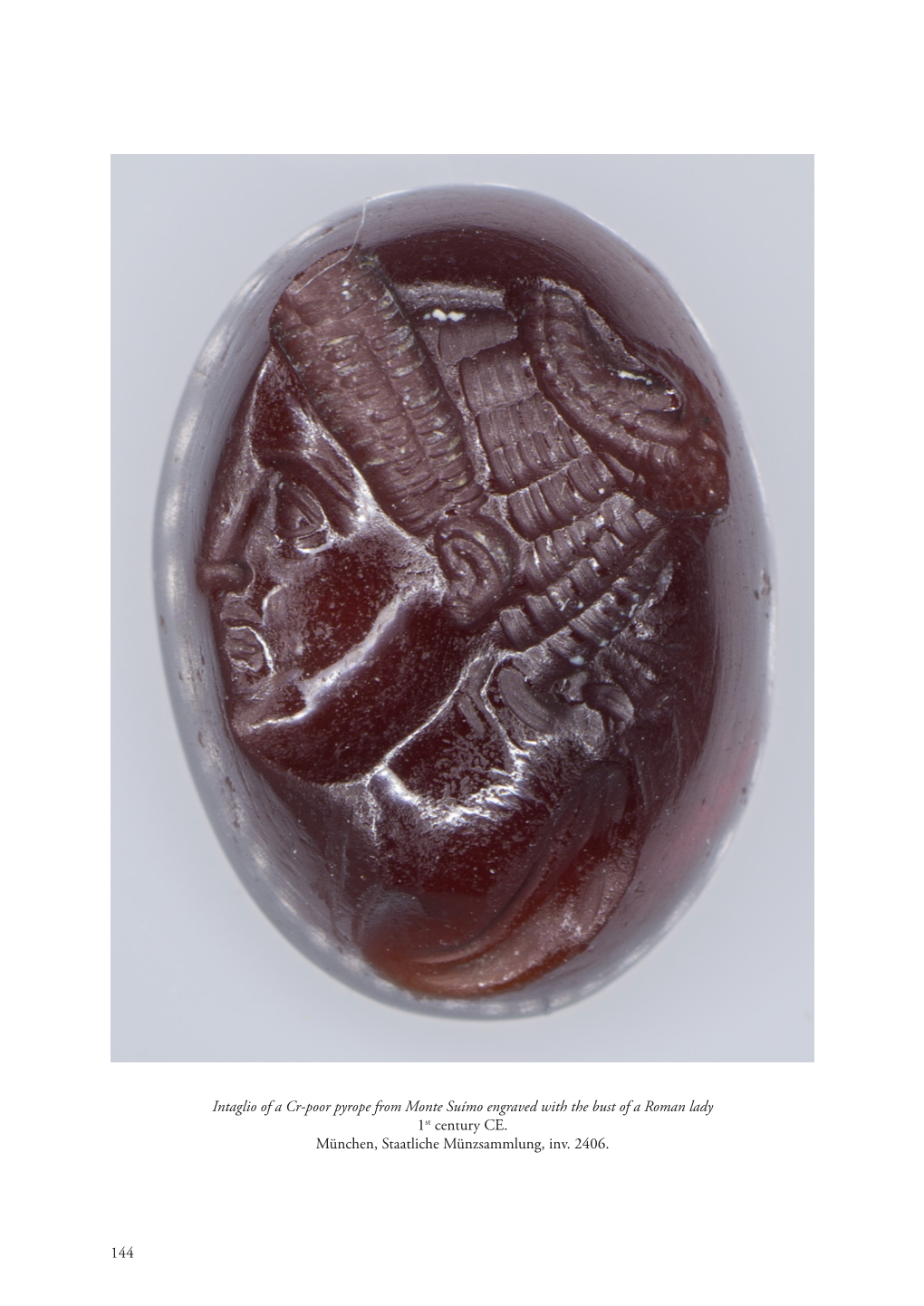

144 Intaglio of a Cr-Poor Pyrope from Monte Suímo Engraved with The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF About Minerals Sorted by Mineral Name

MINERALS SORTED BY NAME Here is an alphabetical list of minerals discussed on this site. More information on and photographs of these minerals in Kentucky is available in the book “Rocks and Minerals of Kentucky” (Anderson, 1994). APATITE Crystal system: hexagonal. Fracture: conchoidal. Color: red, brown, white. Hardness: 5.0. Luster: opaque or semitransparent. Specific gravity: 3.1. Apatite, also called cellophane, occurs in peridotites in eastern and western Kentucky. A microcrystalline variety of collophane found in northern Woodford County is dark reddish brown, porous, and occurs in phosphatic beds, lenses, and nodules in the Tanglewood Member of the Lexington Limestone. Some fossils in the Tanglewood Member are coated with phosphate. Beds are generally very thin, but occasionally several feet thick. The Woodford County phosphate beds were mined during the early 1900s near Wallace, Ky. BARITE Crystal system: orthorhombic. Cleavage: often in groups of platy or tabular crystals. Color: usually white, but may be light shades of blue, brown, yellow, or red. Hardness: 3.0 to 3.5. Streak: white. Luster: vitreous to pearly. Specific gravity: 4.5. Tenacity: brittle. Uses: in heavy muds in oil-well drilling, to increase brilliance in the glass-making industry, as filler for paper, cosmetics, textiles, linoleum, rubber goods, paints. Barite generally occurs in a white massive variety (often appearing earthy when weathered), although some clear to bluish, bladed barite crystals have been observed in several vein deposits in central Kentucky, and commonly occurs as a solid solution series with celestite where barium and strontium can substitute for each other. Various nodular zones have been observed in Silurian–Devonian rocks in east-central Kentucky. -

A Ground Magnetic Survey of Kimberlite Intrusives in Elliott County, Kentucky

Kentucky Geological Survey James C. Cobb, State Geologist and Director University of Kentucky, Lexington A Ground Magnetic Survey of Kimberlite Intrusives in Elliott County, Kentucky John D. Calandra Thesis Series 2 Series XII, 2000 Kentucky Geological Survey James C. Cobb, State Geologist and Director University of Kentucky, Lexington A Ground Magnetic Survey of Kimberlite Intrusives in Elliott County, Kentucky John D. Calandra On the cover: Photomicrographs of olivine phenoc- rysts: (top) a stressed first-generation olivine pheno- cryst and (bottom) a late-stage olivine phenocryst. Thesis Series 2 Series XII, 2000 i UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY Computer and Laboratory Services Section: Charles T. Wethington Jr., President Steven Cordiviola, Head Fitzgerald Bramwell, Vice President for Research and Richard E. Sergeant, Geologist IV Graduate Studies Joseph B. Dixon, Information Technology Manager I Jack Supplee, Director, Administrative Affairs, Research James M. McElhone, Information Systems Technical and Graduate Studies Support Specialist IV Henry E. Francis, Scientist II KENTUCKY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ADVISORY Karen Cisler, Scientist I BOARD Jason S. Backus, Research Analyst Henry M. Morgan, Chair, Utica Steven R. Mock, Research Analyst Ron D. Gilkerson, Vice Chair, Lexington Tracy Sizemore, Research Analyst William W. Bowdy, Fort Thomas Steve Cawood, Frankfort GEOLOGICAL DIVISION Hugh B. Gabbard, Winchester Coal and Minerals Section: Kenneth Gibson, Madisonville Donald R. Chesnut Jr., Head Mark E. Gormley, Versailles Garland R. Dever Jr., Geologist V Rosanne Kruzich, Louisville Cortland F. Eble, Geologist V W.A. Mossbarger, Lexington Gerald A. Weisenfluh, Geologist V Jacqueline Swigart, Louisville David A. Williams, Geologist V, Henderson office John F. Tate, Bonnyman Stephen F. Greb, Geologist IV David A. -

Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana

Report of Investigation 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg 2015 Cover photo by Richard Berg. Sapphires (very pale green and colorless) concentrated by panning. The small red grains are garnets, commonly found with sapphires in western Montana, and the black sand is mainly magnetite. Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology MBMG Report of Investigation 23 2015 i Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 Descriptions of Occurrences ..................................................................................................7 Selected Bibliography of Articles on Montana Sapphires ................................................... 75 General Montana ............................................................................................................75 Yogo ................................................................................................................................ 75 Southwestern Montana Alluvial Deposits........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Rock Creek sapphire district ........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Dry Cottonwood Creek deposit and the Butte area .................................... -

Aktuelles Radenthein 2012/03

Amtliche Mitteilungen, zugestellt durch Post.at Ausgabe 03/2012 | August – November 750 Jahre Pfarre Radenthein 11. BIS 14. OKTOBER DO 11.10. - 19.30 Uhr Jubiläumsvortrag - Rathaussaal Stadtgemeinde FR 12.10. - 18.00 Uhr tt – Sty ni le Einweihung des neu errichteten Kreuzweges Kärntensh n SA 13.10. - 16.00 Uhr c – S Männergeschenke? L Familienmesse e – punkte SA 13.10. - 20.00 Uhr Bier-Geschenkskorb g n e e Benefizkonzert des MGV Kaning 50 verschiedene komplett nur € n h SO 14.10. - 10.00 Uhr c Biere zur Auswahl! s Festmesse mit Bischof Dr. Alois Schwarz a W 38,– www.backhendl.at Sept./Okt. 2 Aktuelles Radenthein | BÜRGERMEISTERBRIEF | IMPRESSUM Liebe Gemeindebürgerinnen und Gemeindebürger! Liebe Leserinnen und Leser! Mit Sorge habe ich in den letzen Eine weitere wichtige Entschei- zwei Monaten die Berichte über dung ist mit den Vertretern des die vielen Unwetterschäden in vie- Landes in Bezug auf die Anbin- len Teilen Österreichs verfolgt und dung des Millstättersee-Radweges wir dürfen dankbar sein, dass wir in an Spittal/Drau und den Draurad- dieser Zeit nicht zu den Betroffenen weg gefallen. Von allen diskutier- gehörten. Dennoch haben die ten Varianten wird der Anschluss Stark regen vom Juli Schäden von über die Liesertaler-Bundesstraße Als ich im letzten Jahr mit GR Martin ca. € 150.000,00 verursacht. Ich erfolgen. Wacker eine Abordnung von Har- möchte mich für die raschen und ley-Bikern in Radenthein begrüßte, effektiven Einsätze bei den Freiwil- Zu einem Tag der offenen Tür lud wurde versprochen, heuer Radent- ligen Feuerwehren und beim Wirt- der Verein VitaminR ein und er- hein in den Charity-Tourkalender schaftshof bedanken. -

Alle Routen Auf

Regeln fürs Trailbiken Grünsee Grünsee Gruft g r e R b a 2232 1. Basiskönnen! Ein fahrtechnisches Können und Grundkondition sind essentiell für ein d k B95 b c a Zgartenalm c o sicheres Fahren. Wichtig beim Bremsen einen Finger zu verwenden, die Bremskraft richtig Alle Routenh auf: www.nockbike.at N h Plattnock c a zu verteilen und die Grundposition anzupassen. b lm 2. Schutzausrüstung tragen! Helm, Protektoren an Rücken, Ellbogen und Beinen sowie 2316 Hofa A10 h Handschuhe. c ba ld 3. Das verwendete Bike! Muss den Streckenbedingungen angepasst und gewartet sein. a p h ä r e n p a r W i o s k W in Großer B k Geeignet ist ein Freeride- oder Downhill-Bike. Tipp: Schutzausrüstung und Bikes kann L N lb an a d c Speikkofel f o h h r man in Verleihstationen ausleihen oder erwerben. aß ch c b a c a a hb Pfannnock b ch ac k n 4. Nur beschilderte Strecken! Befahren und Fahrverbote beachten. Nicht als „Bikestrecke“ fl e o g K b g e Trebesing rr gekennzeichnete Wege dürfen nicht befahren werden. nock/bike Karte beachten. 2254 e u a r S 5. Auf Sicht fahren und auf andere Biker Rücksicht nehmen! Geschwindigkeit und Fahr B99 Ra g c he weise entsprechend dem eigenen Können, dem Gelände, den Witterungsverhältnissen nb Kleiner Speikkofel ac e h Klomnock Speikkofelhütte und der „Verkehrsdichte“ anzupassen. Saureggen 2109 6. Von hinten kommende Mountainbiker! Müssen ihre Fahrspur stets so wählen, dass sie 2331 vorausfahrende, langsamere Biker nicht gefährden. L10 Rosennock Mallnock 7. -

Stand Der Kärntner Biotopkartierung 1990 199-204 ©Naturwissenschaftlicher Verein Für Kärnten, Austria, Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Carinthia II Jahr/Year: 1991 Band/Volume: 181_101 Autor(en)/Author(s): Hartl Helmut Artikel/Article: Stand der Kärntner Biotopkartierung 1990 199-204 ©Naturwissenschaftlicher Verein für Kärnten, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Carinthia II 181., 101. Jahrgang S. 199-2(14 Klagenfurt 1991 Stand der Kärntner Biotopkartierung 1990 Von Helmut H ARTI. Mit 1 Abbildung Im Jahre 1990 wurden 70 neue Biotope im Gelände erfaßt und EDV- mäßig mit dem Programm „BIODAT" gespeichert. Somit ergibt sich ein derzeitiger Stand von 204 schützenswerten Biotopen. Von jedem dieser Kleinlebensräume existiert eine genaue Beschreibung hinsichtlich Stand der Biotopkartierung 1990 A Grauerlen-Auw aider •Hoc hnoore, S c hwingrasen V B äun e, Hecken,Alleen • Seen, Teiche, Tun pel HAI twässer, A1 tarne (Jrua ldreste • Schwarzerlenbrüche Q Graben, Schluchten, Bäche # Standorte selt.Pflanzen ©Hang- u. Ouellnoore £i Trockenrasen X Interess.Steinbrüche U Flach-u. Zw i sc henrtoore "vj B1 unenr e i c he Mageru i esenm B1 unenre ì c he Fettw i esen Abb. 1: Stand der Biotopkartierung 1990. Sollten Ihnen weitere Biotope bekannt sein, bitten wir um Bekanntgabe. 199 ©Naturwissenschaftlicher Verein für Kärnten, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Lage und hervorstechender Pflanzengemeinschaften, eine kartographi- sche Darstellung, einige Bilder und eine Artenliste der dominierenden Pflanzenarten oder Arten, die auf Grund ihrer Seltenheit für einen Schutz dieses Biotops sprechen (interessante Tierarten werden in der Beschreibung berücksichtigt). Dank des Computers ist eine Auswertung nach den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten möglich (z. B. nur „Rote- Liste"-Arten eines Biotops oder Ordnung der Biotope nach Gemein- den, Bezeichnungen, Ö-Karten usw.). -

The World of Pink Diamonds and Identifying Them

GEMOLOGY GEMOLOGY as to what dealers can do to spot them using standard, geologists from Ashton Joint Venture found certain indicator The World of Pink Diamonds inexpensive instruments. The commercial signifcance of minerals (such as ilmenite, chromite, chrome diopside, the various types will also be touched on. and pyrope garnet) in stream-gravel concentrates which indicated the presence of diamond-bearing host rocks. and Identifying Them Impact of Auction Sales Lamproites are special ultrapotassic magnesium-rich In the late 1980s, the public perception surrounding fancy- mantle-derived volcanic rocks with low CaO, Al2O3, Na2O colored diamonds began to change when the 0.95-carat and high K2O. Leucite, glass, K-richterite, K-feldspar and Cr- By Branko Deljanin, Dr Adolf Peretti, ‘Hancock Red’ from Brazil was sold for almost $1 million per spinel are unique to lamproites and are not associated with and Matthias Alessandri carat at a Christie’s auction. This stone was studied by one kimberlites. The diamonds in lamproites are considered to be of the authors (Dr. Adolf Peretti) at that time. Since then, xenocrysts and derived from parts of the lithospheric mantle Dr. Peretti has documented the extreme impact this one that lies above the regions of lamproite genesis. Kimberlites sale has had on subsequent prices and the corresponding are also magmatic rocks but have a different composition recognition of fancy diamonds as a desirable asset class. The and could contain non-Argyle origin pink diamonds. demand for rare colors increased and the media began to play a more active role in showcasing new and previously Impact of Mining Activities unknown such stones. -

Fahrpreise Ausflugs- Und Wanderbus Im Lieser- / Maltatal Und Auf Den Katschberg

Fahrplan-Informationen und Fahrplan-Downloads: Fahrpreise www.kaernten-bus.at Einzelkarte Einzelkarte Einzelkarte Hin&Retour Hin&Retour Hin&Retour Vollpreis Senioren Spar Vollpreis Senioren Spar Gmünd in Kärnten - Maltatal - Kölnbreinsperre Kölnbreinsperre - Maltatal - Gmünd in Kärnten Gmünd in Kärnten - Maltaberg Spittal - Maltaberg 11,50 € 8,00 € 6,00 € 19,20 € 12,40 € 10,00 € Gmünd - Maltaberg 8,20 € 6,30 € 4,50 € 12,90 € 9,00 € 7,10 € gültig ab Dienstag, 29.06.2021 bis Samstag, 25.09.2021 gültig ab Dienstag, 29.06.2021 bis Samstag, 25.09.2021 gültig ab Mittwoch, 30.06.2021 bis Mittwoch, 29.09.2021 Malta - Maltaberg 6,80 € 5,50 € 3,70 € 10,70 € 7,80 € 5,80 € Rennweg - Maltaberg 10,50 € 7,50 € 5,50 € 17,20 € 11,30 € 9,10 € Rufbus Rufbus Rufbus Spittal - Frido Kordon H. 9,40 € 7,00 € 5,00 € 15,10 € 10,20 € 8,20 € Bus fährt nur auf telefonische Bus fährt nur auf telefonische Bus fährt nur auf telefonische Gmünd - Frido Kordon H. 5,30 € 4,70 € 3,10 € 8,20 € 6,60 € 4,80 € Vorbestellung bis 18 Uhr des Vortages Vorbestellung bis 18 Uhr des Vortages Vorbestellung bis 18 Uhr des Vortages Malta - Frido Kordon H. 6,80 € 5,50 € 3,70 € 10,70 € 7,80 € 5,80 € Telefon: +43 (0) 4732 37 175 Telefon: +43 (0) 4732 37 175 Telefon: +43 (0) 4732 37 175 Rennweg - Frido Kordon H. 8,20 € 6,30 € 4,50 € 12,90 € 9,00 € 7,10 € 5132 Spittal/Drau - Gmünd in Kärnten Dienstag 5132 Spittal/Drau - Gmünd in Kärnten Samstag Donnerstag Einzelkarte Einzelkarte Einzelkarte Hin&Retour Hin&Retour Hin&Retour Spittal Millstättersee Bf/Bhf ab 08:36 15:36 07:36 12:36 08:36 14:36 -

Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina by W

.'.' .., Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina By W. F. Wilson and B. J. McKenzie RUTILE GUMMITE IN GARNET RUBY CORUNDUM GOLD TORBERNITE GARNET IN MICA ANATASE RUTILE AJTUNITE AND TORBERNITE THULITE AND PYRITE MONAZITE EMERALD CUPRITE SMOKY QUARTZ ZIRCON TORBERNITE ~/ UBRAR'l USE ONLV ,~O NOT REMOVE. fROM LIBRARY N. C. GEOLOGICAL SUHVEY Information Circular 24 Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina By W. F. Wilson and B. J. McKenzie Raleigh 1978 Second Printing 1980. Additional copies of this publication may be obtained from: North CarOlina Department of Natural Resources and Community Development Geological Survey Section P. O. Box 27687 ~ Raleigh. N. C. 27611 1823 --~- GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SECTION The Geological Survey Section shall, by law"...make such exami nation, survey, and mapping of the geology, mineralogy, and topo graphy of the state, including their industrial and economic utilization as it may consider necessary." In carrying out its duties under this law, the section promotes the wise conservation and use of mineral resources by industry, commerce, agriculture, and other governmental agencies for the general welfare of the citizens of North Carolina. The Section conducts a number of basic and applied research projects in environmental resource planning, mineral resource explora tion, mineral statistics, and systematic geologic mapping. Services constitute a major portion ofthe Sections's activities and include identi fying rock and mineral samples submitted by the citizens of the state and providing consulting services and specially prepared reports to other agencies that require geological information. The Geological Survey Section publishes results of research in a series of Bulletins, Economic Papers, Information Circulars, Educa tional Series, Geologic Maps, and Special Publications. -

Aktuelles Radenthein 2013/01

Amtliche Mitteilungen, zugestellt durch Post.at Ausgabe 01/2013 | März – Juni mit dem Radentheiner Reindl-Reindling von Sieglinde Kohlmayer, Tel. 0676/6887616 Frohe Ostern INHALT: Seite 10 Aus dem Standesamt „ALL-INCLUSIVE” …OHNE WENN UND ABER Seite 42-43 Sagamundo & Granatium Waschen-Schneiden–Fönen inkl. Dauerwelle oder Farbe oder Tönung Seite 47 Granatstadt Radenthein oder (Strähnen + €10,–) Seite 48-49 Veranstaltungen € 64,90 www.frisuren-krug.at 2 Aktuelles Radenthein | BÜRGERMEISTERBRIEF | IMPRESSUM Liebe Gemeindebürgerinnen und Gemeindebürger! Liebe Leserinnen und Leser! Die Landtagswahl ist vorüber und Die Lösung wurde vom Linienbetrei- angesichts der Veränderungen, die ber insofern angeboten, als dass die sich in unserem Bundesland ergeben Gemeinden einen Teil der Abgangs- haben, werden auch die Gemeinden deckung übernehmen sollen. Nach- die Zusammenarbeit mit den ge- dem die Kärntner Gemeinden große wählten Entscheidungsträgern auf- Summen in den Verkehrsverbund nehmen. Unser Ziel in Radenthein ist einzahlen war man in Radenthein der klar definiert und die Konsolidierung Meinung, dass eine reine Aufteilung des Finanzhaushaltes ist unser Auf- von Abgängen auf die Kommunen trag. Aber in vielen Bereichen haben von wenig Fantasie zeugt. Attraktive wir Handlungsbedarf und erwarten Fahrplangestaltung und der Einsatz uns auch entsprechende Hilfe. von bedarfsorientierten Fahrzeugen würde wesentlich zu einer wirtschaft- Erfreulicherweise konnten wir den licheren Mehrnutzung beitragen. Auftrag für das neue örtliche Ent- Nachdem letztendlich der Auftei- Nachdem es am Friedhof in Raden- wicklungskonzept erteilen und damit lungsschlüssel geändert wurde, hat thein dringenden Bedarf an Sanier- werden die dringenden Grundlagen die Gemeinde Radenthein für 2013 ungsarbeiten gibt, wird heuer end- für die erforderlichen Umwidmungen einem Kostenbeitrag zugestimmt lich die Hauptstiege und diverse im Bereich Döbriach nun erstellt. -

Mineral Inclusions in Four Arkansas Diamonds: Their Nature And

AmericanMineralogist, Volume 64, pages 1059-1062, 1979 Mineral inclusionsin four Arkansas diamonds:their nature and significance NnNrBr.r.B S. PeNrareo. M. Geny NBwroN. Susnennyuoe V. GocINENI, CsnRr-ns E. MELTON Department of Chemistry, University of Georgia eNo A. A. GnnoINI Department of Geology, University of Georgia Athens,Georgia 30602 Abstract Totally-enclosed inclusions recovered from four Arkansas diamonds by burning in air at 820" C are identified by XRD and Eoex analysesas: (l) enstatite,olivine, pyrrhotite + pent- landite, (2) eclogitic garnet, (3) enstatite+ peridotitic garnet + chromite, olivine + pyrrho- tite, pyrrhotite, pentlandite,pyrite + pyrrhotite, pentlandite * a nickel sulfide,(4) diamond, enstatite,magnetite. This is the first report of nickel sulfide in diamond. A review of in- clusionsfound in Arkansasdiamonds showsa similarity with those from world-wide local- ities, and indicatesa global consistencyin diamond-formingenvironments. Introduction opaque and transparent totally-enclosedinclusions were apparentunder binocular microscopeexamina- impermeable, Since diamonds are relatively inert, tion. The 0.45 ct. stone was colorlessand of elon- pre- and hard, inclusions therein are about as well gated rounded shapewith a highly polished surface. pro- served as they could possibly be. Their study Four inclusions were detected.The 0.50 ct. crystal wherein vides entghtment about the environment was a colorlessrounded tetrahexahedronwith a diamondsformed. cleavageplane on one sideand containedtransparent A considerable literature exists on diamond in- and opaque inclusions. The 0.62 ct. diamond was Afri- clusions,but most of it dealswith diamondsof also colorlessand of rounded tetrahexahedralform. can, Siberian, and South American origin (e.9., Severalrelatively large flat opaque inclusions ("car- Meyer and Tsai, 1976;Mitchell and Giardtni,1977; bon spots") were observed.All the diamonds were Orlov, 1977).ln all, about thirty minerals have been free ofdetectable surfacecleavage cracks. -

The Garnet Carbuncle in Early Medieval Europe

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-15-2020 Sacred Blood and Burning Coal: The Garnet Carbuncle in Early Medieval Europe Sinead L. Murphy CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/591 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Sacred Blood and Burning Coal: The Garnet Carbuncle in Early Medieval Europe by Sinead Murphy Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York Spring 2020 May 15th, 2020 Cynthia Hahn Date Thesis Sponsor May 15th, 2020 Maria Loh Date Second Reader i Table of Contents List of Illustrations ii Introduction: Garnets in the Merovingian Period…………………………………………………1 Chapter 1: Garnet in Classical and Early Medieval Texts……………………………………….11 I. Carbuncle and Anthrax in Classical and Early Medieval Lapidaries II. Carbuncle in Scripture and Christian Lapidaries III. Pagan Influence on the Christian Symbolism of Garnets Chapter 2: Garnets in Everyday Life…………………………………………………………….34 I. Garnet Jewelry in Frankish Costume II. Garnet Ecclesiastical Objects Chapter 3: The Role of Garnets in Christian Funerary Ritual…………………………………...49 I. Prayers for the Dead II. Grave Goods and Dressed Burials III. Metaphorical Representations of Carbuncle Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….59 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..60 Illustrations………………………………………………………………………………………64 i List of Illustrations Fig. 1: Pair of quatrefoil mounts, Early Byzantine, 2nd half of 5th century.