Making the Connections: the Cross-Sector Benefits of Supporting Bus Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Heatherwick, Architecture's Showman

Thomas Heatherwick, Architecture’s Showman His giant new structure aims to be an Eiffel Tower for New York. Is it genius or folly? February 26, 2018 | By IAN PARKER Stephen Ross, the seventy-seven-year-old billionaire property developer and the owner of the Miami Dolphins, has a winningly informal, old-school conversational style. On a recent morning in Manhattan, he spoke of the moment, several years ago, when he decided that the plaza of one of his projects, Hudson Yards—a Doha-like cluster of towers on Manhattan’s West Side—needed a magnificent object at its center. He recalled telling him- self, “It has to be big. It has to be monumental.” He went on, “Then I said, ‘O.K. Who are the great sculptors?’ ” (Ross pronounced the word “sculptures.”) Before long, he met with Thomas Heatherwick, the acclaimed British designer of ingenious, if sometimes unworkable, things. Ross told me that there was a presentation, and that he was very impressed by Heatherwick’s “what do you call it—Television? Internet?” An adviser softly said, “PowerPoint?” Ross was in a meeting room at the Time Warner Center, which his company, Related, built and partly owns, and where he lives and works. We had a view of Columbus Circle and Central Park. The room was filled with models of Hudson Yards, which is a mile and a half southwest, between Thirtieth and Thirty-third Streets, and between Tenth Avenue and the West Side Highway. There, Related and its partner, Oxford Properties Group, are partway through erecting the complex, which includes residential space, office space, and a mall—with such stores as Neiman Marcus, Cartier, and Urban Decay, and a Thomas Keller restaurant designed to evoke “Mad Men”—most of it on a platform built over active rail lines. -

INTRODUCTION En Septembre 2020, Luca De Meo a Annoncé La Création

INTRODUCTION En septembre 2020, Luca De Meo a annoncé la création d’Alpine F1 Team en s’appuyant sur l’équipe du Groupe Renault, l’une des plus historiques et fructueuses de l’histoire de la Formule 1. Déjà reconnu pour ses records et succès en endurance et en rallye, le nom Alpine trouve naturellement sa place dans l’exigence, le prestige et la performance de la F1. La marque Alpine, symbole de sportivité, d’élégance et d’agilité, désignera le châssis et rendra hommage à l’expertise à l’origine de l’A110. Pour Alpine, il s’agit d’une étape clé pour accélérer le développement et le rayonnement de la marque. Le moteur de l’écurie continuera de bénéficier de l’expertise unique du Groupe Renault dans les motorisations hybrides, dont la dénomination Renault E-Tech sera conservée. Luca De Meo, directeur général du Groupe Renault : « C’est une véritable joie de voir le nom puissant et vibrant d’Alpine sur une Formule 1. De nouvelles couleurs, un nouvel encadrement, des projets ambitieux : il s’agit d’un nouveau départ, basé sur quarante ans d’histoire. Nous allierons les valeurs d’authenticité, d’élégance et d’audace d’Alpine à notre expertise en matière d’ingénierie et de châssis. C'est toute la beauté d'être constructeur en Formule 1. Nous affronterons les plus grands noms pour des courses spectaculaires faites et suivies par des passionnés enthousiastes. J’ai hâte que la saison commence. » Alpine aujourd’hui et demain Dans le cadre du plan stratégique « Renaulution » du Groupe Renault, Alpine a dévoilé ses projets à long terme pour positionner la marque à la pointe de l’innovation. -

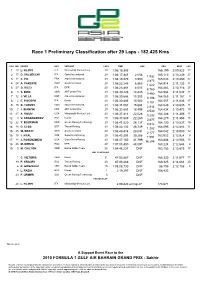

Race 1 Preliminary Classification After 29 Laps - 182.425 Kms

Race 1 Preliminary Classification after 29 Laps - 182.425 Kms POS NO DRIVER NAT ENTRANT LAPS TIME GAP KPH BEST LAP 1 20 L. FILIPPI ITA MalaysiaQi-Meritus.Com 29 1:06:15.383 165.199 2:09.823 27 2 17 D. VALSECCHI ITA iSport International 29 1:06:17.441 2.058 165.113 2:10.239 27 1.932 3 11 C. PIC FRA Arden International 29 1:06:19.373 3.990 165.033 2:10.450 27 2.873 4 24 A. PARENTE POR Scuderia Coloni 29 1:06:22.246 6.863 164.914 2:11.132 11 1.222 5 27 G. RICCI ITA DPR 29 1:06:23.468 8.085 164.863 2:10.716 27 6.760 6 8 S. BIRD GBR ART Grand Prix 29 1:06:30.228 14.845 164.584 2:11.032 11 0.460 7 12 J. VILLA ESP Arden International 29 1:06:30.688 15.305 164.565 2:11.167 9 0.198 8 2 E. PISCOPO ITA Dams 29 1:06:30.886 15.503 164.557 2:11.636 17 0.181 9 16 O. TURVEY GBR iSport International 29 1:06:31.067 15.684 164.549 2:10.605 11 2.814 10 7 J. BIANCHI FRA ART Grand Prix 29 1:06:33.881 18.498 164.434 2:10.472 10 3.530 11 21 A. ROSSI USA MalaysiaQi-Meritus.Com 29 1:06:37.411 22.028 164.288 2:11.396 11 0.232 12 3 V. -

Driving Experience Public Speaking

Phone : +44 7900 885843 | [email protected] www.karunchandhok.com | www.twitter.com/karunchandhok | www.youtube.com/karunracing DRIVING EXPERIENCE 2018 Goodwood Revival: Whitsun Trophy, Fastest lap of the weekend across all categories. 2017 World Endurance Championship (selected rounds) and Le Mans: Tockwith Motorsport (LMP2). 9th in class at Le Mans British LMP3 Cup (Two races): T-Sport, 3rd and 4th places 2016 European Le Mans Series: Murphy Prototypes (LMP2) 2015 Le Mans 24 Hours: Murphy Prototypes, 5th in class (LMP2) Goodwood Revival St.Mary’s Trophy: Swiftune Mini, Top placed Mini in race 2014-2015 FIA Formula E Championship: Mahindra Racing, only Indian driver 2014 Dubai 24 Hours: Nissan GT Academy, 3rd in class (SP2) European Le Mans Series: Murphy Prototypes Le Mans 24 Hours: Murphy Prototypes 2013 Le Mans 24 Hours: Murphy Prototypes, 6th in class (LMP2) FIA GT Series: Seyffarth Motosport Goodwood Revival Tourist Trophy Race: Pearson Engineering, Jaguar E-Type 2012 World Endurance Championship: JRM Racing, 3rd in class (LMP1 Privateers) Le Mans 24 Hours: JRM Racing, 6th overall, 2nd in class (LMP1 Privateers), first Indian to race at Le Mans Race of Champions (Asia): Team India, 1st overall 2011 FIA Formula One World Championship: Team Lotus, race and reserve driver ; Simulator development driver 2010 FIA Formula One World Championship: Hispania Racing Team, race driver, only Indian in Championship ; Completed extensive simulator work at Mclaren simulator on behalf of Force India F1. 2009 Dubai 24 Hours: Empire Motorsports -

Davide Signed with Alpine F1 Team in January 2021 As

ALPINE F1 TEAM PRESS PACK Already recognised for its records It is part of Groupe Renault’s Luca De Meo, CEO Groupe That’s the beauty of racing as In September 2020, Luca De Meo, and successes in endurance strategy to clearly position Renault: “It is a true joy to see a works team in Formula 1. announced the creation of Alpine F1 Team, and rallying, the Alpine name each of its brands. For Alpine, the powerful, vibrant Alpine We will compete against the naturally finds its place in the this is a key step to accelerate name on a Formula One car. biggest names, for spectacular a renaissance of Groupe Renault’s F1 team, high standards, prestige and the development and influence New colours, new managing car races made and followed one of F1’s most historic and successful. performance of Formula 1. The of the brand. Renault remains team, ambitious plans: it’s a new by cheering enthusiasts. I can’t Alpine brand, a symbol of sporting an integral part of the team, beginning, building on a 40-year wait for the season to start.” prowess, elegance and agility, with the hybrid power unit history. We’ll combine Alpine’s will be designated to the chassis retaining its Renault E-Tech values of authenticity, elegance and pay tribute to the expertise moniker and unique expertise and audacity with our in-house that gave birth to the A110. in hybrid powertrains. engineering & chassis expertise. ALPINE F1 TEAM | PRESS PACK | 2021 Alpine Today and Tomorrow As part of Groupe Renault’s strategic plan ‘Renaulution’, Alpine unveiled its long-term plans to position the brand at the forefront of Groupe Renault’s innovation. -

A Green Bus for Every Journey

A Green Bus For Every Journey Case studies showing the range of low emission bus technologies in use throughout the UK European engine Bus operators have invested legislation culminating significant sums of money and in the latest Euro VI requirements has seen committed time and resources the air quality impact of in working through the early new buses dramatically challenges on the path to improve but, to date, carbon emissions have not been successful introduction. addressed in bus legislation. Here in Britain, low carbon Investment has been made in new bus technologies and emission buses have been under refuelling infrastructure, and even routing and scheduling development for two decades or have been reviewed in some cases to allow trials and more, driven by strong Government learning of the most advanced potential solutions. policy. Manufacturers, bus operators A number of large bus operators have shown clear and fuel suppliers are embracing leadership by embedding low carbon emission buses into the change, aware that to maintain their sustainability agenda to drive improvements into the their viability, buses must be amongst environmental performance of their bus fleet. the cleanest and most carbon-efficient vehicles on the road. Almost 4,000 There have, of course, been plenty of hurdles along the Low Carbon Emission Buses (LCEB) are way; early hybrid and electric buses experienced initial now operating across the UK, with 40% of reliability issues like any brand new technology, but buses sold in 2015 meeting the low carbon through open collaboration the technology has rapidly requirements. These buses have saved over advanced and is now achieving similar levels of reliability 55,000 tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions as that employed in gas buses and conventional diesel (GHG) per annum compared with the equivalent buses, with warranties extending and new business number of conventional diesel buses. -

Clean Vehicle Retrofit Accreditation Scheme – Open List

Delivered in partnership with Supported by Clean Vehicle Retrofit Accreditation Scheme – Open List CVRAS approved companies and emission reduction systems - Version: 34 Date: 13.04.2021 This listing contains details of companies and their systems approved under the scheme requirements, along with their contact information (where available) and the categories of vehicle to which their systems can be applied in order to make the vehicle Clean Air Zone compliant. Company information Technology Product Application status Vehicle Approved vehicle applications Category Eminox Ltd Retrofit exhaust Eminox Approved Bus Double Deck Buses Single Deck Buses (Gainsborough, UK) after-treatment SCRT® system (SCRT) (DPF+SCR • Cummins ISBe 6.7 • Scania DC901 9.0 litre [email protected] with urea litre Euro IV & V Euro III, IV and V Tel: +44(0)1427 810088 Adblue) powered powered • Volvo D5F 4.8 litre • Cummins ISBe 5.9 www.eminox.com Euro IV & V litre Euro III powered powered • Cummins ISBe 4.5 • Volvo D9B 9.4 litre litre Euro IV and V Euro IV & V powered powered • Volvo D7C 7.3 litre • Scania DC901 9.0 Euro III and IV litre Euro III, IV and powered V powered • Volvo D7E 7.1 litre • Volvo D7C 7.3 litre Euro IV and V Euro III powered powered • Volvo D7E 7.1 litre • Mercedes Benz Euro IV & V OM904LA 4.25 litre powered Euro IV & V powered (e.g. Optare Solo) Page 1 of 10 Version: 34 Date: 13.04.2021 Delivered in partnership with Supported by Retrofit exhaust Eminox Approved Refuse • Dennis Eagle Elite with Volvo D7C 7litre Euro V after-treatment SCRT® Collection -

The Londons New Routemaster Free

FREE THE LONDONS NEW ROUTEMASTER PDF Tony Lewin,Thomas Heatherwick | 160 pages | 12 May 2014 | Merrell Publishers Ltd | 9781858946245 | English | London, United Kingdom Heatherwick Studio | Design & Architecture | New Routemaster Looks like The Londons New Routemaster article is a bit old. Be aware that information may have changed since it was published. Earlier this year, as he was stepping off the back of a New Routemaster, a friend of mine had his knee twatted by a door mechanism that was channeling the till from Open All Hours. Reeling from the pain, he wondered whether it was the The Londons New Routemaster or the bus that was to blame. Actually, it was Boris Johnson's fault. According to a promise Johnson had made to Londoners, that door was never going to be there in the first place. In his former guise as Mayor of London back inJohnson had pledged — as a flagship part of his manifesto, mind — that every New Routemaster would have a 'hop on, hop off' option, each vehicle manned by a conductor. It was going to be just like in the good old days. If that sounded too good financially reckless to be true, it was. Bythe open platform, and accompanying The Londons New Routemaster, were consigned The Londons New Routemaster the scrapheap. The conductors' job, by the way, had never been to sell tickets, which they couldn't. It was, presumably, to ensure that the mayor's encouragement for Londoners to leap at moving vehicles with Flynn-esque derring-do, didn't end up in a flurry of law suits. -

Renault Motorsport Strategy

Press Kit 2016 RENAULT MOTORSPORT STRATEGY Contents 01 Introduction 03 02 Renault Sport Racing 07 Q&A with Cyril Abiteboul 08 Q&A with Guillaume Boisseau 10 Q&A with Frédéric Vasseur 11 Q&A With Bob Bell 12 Q&A with Nick Chester 13 Q&A with Rémi Taffin 14 Renault R.S.16 Technical Specification 16 Renault R.E.16 Technical Specification 17 03 Jolyon Palmer 18 Kevin Magnussen 20 Esteban Ocon 22 04 Renault Sport Academy 24 Oliver Rowland 25 Jack Aitken 27 Louis Delétraz 28 Kevin Joerg 29 05 Renault Sport Formula One Team within the Renault-Nissan Alliance 30 Renault Sport Formula One Team Partners 31 06 Renault: 115 Years of Motorsport Success 34 Renault Motorsport Activities 40 Renault Sport Cars 42 Technology Transfer 45 Renault Press [email protected] www.renaultsport.com 2 Press Kit 3 February 2016 01 Introduction The forging of Renault Sport Racing and Renault Sport Cars is the next chapter in an already compelling story. For more than 115 years Renault has embraced the challenge of motorsport in multiple guises. It recognised the value of competitive activities for technical and commercial gain: in December 1898 Louis Renault drove the Type A Voiturette up the steepest street in Paris, the rue Lepic. The first orders for the ground-breaking car with direct drive flooded in. In 1902 the nimble, lightweight Type K, fitted with Renault’s first 4-cylinder engine, took victory in the Paris-Vienna rally. Again, many more cars were sold. Going through the years, in 1977 Renault introduced the first-ever turbocharged car to F1. -

When It Came to Recruiting Customer Assistants for the New

Recruitment | Psychology When it came to recruiting Customer Assistants for the New Routemasters, London United opted to bring in psychologists to help identify candidates with good customer skills. OPC Assessment helped with psychometric tests, an approach that could grow Selecting the right people is a vital assessment centre was working. The deciding factor for the success of any psychologists took a closer look at organisation. For many industries, how applicants performed on each teaming up with psychologists to assessment tool at the assessment design a recruitment process is centre, and how they performed on second nature; however, this is not the job. commonplace in the bus industry. The analysis revealed that those London United Busways has who performed really well on the shaken things up by teaming up with assessment tools equally performed a leading provider of psychometric really well on the job, including tests, OPC Assessment, to help punctuality and customer service. It recruit its Customer Assistants for the became apparent that through this New Routemaster buses in London. combination of customer-specific The Customer Assistants’ role on psychometric tests, a customer- the New Routemaster is like no other. orientated group exercise and Their role is not to check tickets, but a competency-based interview, rather assist tourists around London. London United was able to run A great deal of travel knowledge on an efficient and effective selection tourist sights and transport links process and recruit high-performing around London is necessary, but to employees. make sure it is a pleasant journey for all also requires great customer service Leading the way forward skills. -

Thomas Heatherwick Presentation March 2021

Thomas Heatherwick Designing the Extraordinary Hazel Frith March 2021 UK Pavilion Shanghai 2010 • Born 17 February 1970, now 51 • Attended Sevenoaks School • Studied what was then ‘Wood, Metal, Glass and Ceramics’, now Three-Dimensional Design, at Manchester Polytechnic • Followed by MA Royal College of Art • Mother jeweller, grandmother textile designer, great grandfather owned Jaeger Heatherwick Studio philosophy ‘The discipline of ideas’ Please note all images copyright Heatherwick Studio unless stated Three dimensional design - not multidisciplinary architecture, sculpture, furniture, metalwork, fashion Early Work Kiosk/Pavilion 1991-2 • Now owned by Cass Foundation Goodwood Sculpture Park Early Work Gazebo 1994 • RCA final project • Sponsored by Terence Conran, built in his garden • Tilting stacks of birch ply support each other structurally • 18 feet high Heatherwick Studio Founded 1994 Harvey Nichols Facade 1997 London Fashion Week • First major public design project • Ribbon of laminated birch ply winding in and out of shop frontage • ‘Playful urban surrealism’ - The Architectural Review • Won a D&AD Gold Award Materials House 1998-9 Materials Gallery, Science Museum, London • Lottery funded commission • Combines 213 different materials built up in undulating layers • Intended to be exploratory and tactile • Library describing the materials adjacent Photographs Science Museum Chandelier - Bleigiessen 2002 Wellcome Trust • 42,000 droplets of glass suspended on 27,000 high tensile wires • Hanging down through 8 floors Photography Wellcome -

Ready for a Changing Journey

04 05 P The road beyond P Motor sport COVID-19: how prepares to fuel travel is adapting up for the future / The pandemic has had / Pursuing sustainability, COVER a huge impact on mobility POWER the pinnacle of motor STORY patterns, but which trends SHIFT sport is researching are here to stay? advanced fuels 04 06 P Racing towards P Jochen Rindt: sustainability Formula 1’s on two wheels lost champion / Formula E driver Lucas / Marking 50 years since ssue ELECTRIC Di Grassi is on a mission TRIUMPH AND the death of grand prix #32 DREAMS to take green motor sport TRAGEDY racing’s only posthumous to the limits – by scooter title-winner Ready for a changing journey FIAAutoMagazine_11_20.indd 1 02.11.20 16:01 AUTO MAGAZINE • 280 x 347 mm PP • Visuel : PILOT SPORT • Remise le 4 novembre • Parution 2020 BoF • BAT MICHELIN PILOT SPORT VICTORIES IN A ROW AT THE HOURS OF LE MANS t-Ferrand. – MFP Michelin, SCA, capital social de 504 000 004 €, 855 200 507 RCS Clermont-Ferrand, place des Carmes-Déchaux, 63000 Clermon Michelin Pilot Sport The winning tire range. Undefeated at The 24 Hours of Le Mans since 1998. MICHELIN Pilot Sport (24 Hours of Le Mans Winner), MICHELIN Pilot Sport Cup 2 Connect, MICHELIN Pilot Sport 4S. MICH_2011010_Pilot_Sport_560x347_Auto_Magazine.indd Toutes les pages 04/11/2020 18:02 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE FIA Dear reader, dear friend, Editorial Board: Jean Todt, Gérard Saillant, THE FIA THE FIA FOUNDATION Freedom of movement is one of the great benets of everyday life that Saul Billingsley, Olivier Fisch Editor-In-Chief: Justin Hynes in the past many of us have too often take for granted.