Lowcvp by E4tech with Cardiff Business School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toys for the Collector

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester Director Shuttleworth Director Director Toys for the Collector Tuesday 10th March 2020 at 10.00 PLEASE NOTE OUR NEW ADDRESS Viewing: Monday 9th March 2020 10:00 - 16:00 9:00 morning of auction Otherwise by Appointment Special Auction Services Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL (Sat Nav tip - behind SPX Flow RG14 5TR) Dave Kemp Bob Leggett Telephone: 01635 580595 Fine Diecasts Toys, Trains & Figures Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Dominic Foster Graham Bilbe Adrian Little Toys Trains Figures Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price Order of Auction 1-173 Various Die-cast Vehicles 174-300 Toys including Kits, Computer Games, Star Wars, Tinplate, Boxed Games, Subbuteo, Meccano & other Construction Toys, Robots, Books & Trade Cards 301-413 OO/ HO Model Trains 414-426 N Gauge Model Trains 427-441 More OO/ HO Model Trains 442-458 Railway Collectables 459-507 O Gauge & Larger Models 508-578 Diecast Aircraft, Large Aviation & Marine Model Kits & other Large Models Lot 221 2 www.specialauctionservices.com Various Diecast Vehicles 4. Corgi Aviation Archive, 7. Corgi Aviation Archive a boxed group of eight 1:72 scale Frontier Airliners, a boxed group of 1. -

March 2020 After 28 Years of Service with the Company, Fifteen of Which As CFO

NFI GROUP INC. Annual Information Form March 16, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS BUSINESS OF THE COMPANY ............................................................................................................................... 2 CORPORATE STRUCTURE ..................................................................................................................................... 3 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS .................................................................................................. 4 Recent Developments ........................................................................................................................................... 4 DESCRIPTION OF THE BUSINESS ......................................................................................................................... 7 Industry Overview ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Company History ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Business Strengths .............................................................................................................................................. 10 Corporate Mission, Vision and Strategy ............................................................................................................. 13 Environmental, Social and Governance Focus .................................................................................................. -

(By Email) Our Ref: MGLA040121-2978 29 January 2021 Dear Thank You for Your Request for Information Which the GLA Received on 4

(By email) Our Ref: MGLA040121-2978 29 January 2021 Dear Thank you for your request for information which the GLA received on 4 January 2021. Your request has been dealt with under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. You asked for: Can I request to see the Mayor’s communications with the British bus manufacturers Alexander Dennis, Optare & Wrightbus from May 2016 to present day under current Mayor Sadiq Khan Our response to your request is as follows: Please find attached the information the GLA holds within scope of your request. If you have any further questions relating to this matter, please contact me, quoting the reference at the top of this letter. Yours sincerely Information Governance Officer If you are unhappy with the way the GLA has handled your request, you may complain using the GLA’s FOI complaints and internal review procedure, available at: https://www.london.gov.uk/about-us/governance-and-spending/sharing-our- information/freedom-information Optare Group Ltd th 20 July 2020 Hurricane Way South Sherburn in Elmet Mr. Sadiq Khan Leeds, LS25 6PT, UK T: +44 (0) 8434 873 200 Mayor of London F: +44 (0) 8434 873 201 Greater London Authority E: [email protected] City Hall, W: www.optare.com London SE1 2AA Dear Mayor Khan, Re: The Electrification of London Public Transport Firstly, let me show my deep appreciation for your tireless efforts in tackling the unprecedented pandemic crisis in London. I am confident that under your dynamic leadership, London will re-emerge as a vibrant hub of business. On Friday 17th July, I took on the role of Chairman of Optare PLC. -

Automotive Sector in Tees Valley

Invest in Tees Valley A place to grow your automotive business Invest in Tees Valley Recent successes include: Tees Valley and the North East region has April 2014 everything it needs to sustain, grow and Nifco opens new £12 million manufacturing facility and Powertrain and R&D plant develop businesses in the automotive industry. You just need to look around to June 2014 see who is already here to see the success Darchem opens new £8 million thermal of this growing sector. insulation manufacturing facility With government backed funding, support agencies September 2014 such as Tees Valley Unlimited, and a wealth of ElringKlinger opens new £10 million facility engineering skills and expertise, Tees Valley is home to some of the best and most productive facilities in the UK. The area is innovative and forward thinking, June 2015 Nifco announces plans for a 3rd factory, helping it to maintain its position at the leading edge boosting staff numbers to 800 of developments in this sector. Tees Valley holds a number of competitive advantages July 2015 which have helped attract £1.3 billion of capital Cummins’ Low emission bus engine production investment since 2011. switches from China back to Darlington Why Tees Valley should be your next move Manufacturing skills base around half that of major cities and a quarter of The heritage and expertise of the manufacturing those in London and the South East. and engineering sector in Tees Valley is world renowned and continues to thrive and innovate Access to international markets Major engineering companies in Tees Valley export Skilled and affordable workforce their products around the world with our Tees Valley has a ready skilled labour force excellent infrastructure, including one of the which is one of the most affordable and value UK’s leading ports, the quickest road connections for money in the UK. -

PACCAR Inc (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2019 or ☐ Transition Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the transition period from ____ to ____. Commission File Number 001-14817 PACCAR Inc (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 91-0351110 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 777 - 106th Ave. N.E., Bellevue, WA 98004 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code (425) 468-7400 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Trading Symbol(s) Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, $1 par value PCAR The NASDAQ Global Select Market LLC Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: NONE Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

The Stagflation Crisis and the European Automotive Industry, 1973-85

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de la Universitat de Barcelona The stagflation crisis and the European automotive industry, 1973-85 Jordi Catalan (Universitat de Barcelona) The dissemination of Fordist techniques in Western Europe during the golden age of capitalism led to terrific rates of auto production growth and massive motorization. However, since the late 1960s this process showed signs of exhaustion because demand from the lowest segments began to stagnate. Moreover, during the seventies, the intensification of labour conflicts, the multiplication of oil prices and the strengthened competitiveness of Japanese rivals in the world market significantly squeezed profits of European car assemblers. Key companies from the main producer countries, such as British Leyland, FIAT, Renault and SEAT, recorded huge losses and were forced to restructure. The degree of success in coping with the stagflation crisis depended on two groups of factors. On the one hand, successful survival depended on strategies followed by the firms to promote economies of scale and scope, process and product innovation, related diversification, internationalization and, sometimes, changes of ownership. On the other hand, firms benefited from long-term path-dependent growth in their countries of origin’s industrial systems. Indeed, two of the main winners of the period, Toyota and Volkswagen, can rightly be seen as outstanding examples of Confucian and Rhine capitalism. Both types of coordinated capitalism contributed to the success of their main car assemblers during the stagflation slump. However, since then, global convergence with Anglo-Saxon capitalism may have eroded some of the institutional bases of their strength. -

Mechanical Engineering Where Have Bath Graduates Gone?

Mechanical Engineering Where have Bath graduates gone? The University of Bath has an excellent record of graduate employment, and often features near the top in any league tables. A large number of employers visit the university and are keen to recruit our graduates; some target only a small number of universities, of which Bath is usually one. Every year we collect information on what graduates are doing 6 months after graduation. The following shows examples of job titles, employers and further study for first degree graduates (UK and Other EU domiciled) of the Department of Mechanical Engineering$ for 2016. Date of census: 12 January 2017. Work & Combined Work / Further Study Modelling and Simulation Engineer: AKKA Aeroconseil UK Accountant / Audit Trainee: Barnes Roffe Officer Cadet: Royal Air Force Account Executive: AKJ Associates Pilot: Royal Air Force Accounts Payable Input Assistant: Liberata Production / Process Engineer: Martin-Baker, Analyst: Alvarez & Marsal, CIL Management Preformed Windings Consultants, North Highland Project Analyst: Quick Release Applications Engineer: Cosworth Quality Engineer: Jaguar Land Rover Assembly Operative: Dextra Lighting Ski Instructor: Whistler Blackcomb Barman / Barista: Bill's Restaurant Software Developer: BBC, FDM Group, Chief Technical Officer: Instant Makr Strategy Consultant: IBM, PwC Composite Components Designer: Aero Systems Engineer: Controlled Power Vodochody Technologies Consultant: Newton Europe Systems Operator: Hawkeye Innovations Cricket System Operator: Hawk-Eye Innovations Technology Graduate: Sky Data Analyst: Hammersmith and Fulham General Trainee Airspace Change Specialist: NATS Practice Federation, Quick Release Trainee Patent Attorney: Keltie, Wynne-Jones IP Design / Development Engineer: Baker Perkins, Coalesce Product Development, CooperVision, Working in start-up company, freelance or self- Cosworth, DCA Design International, Domin Fluid employed*. -

An Attractive Value Proposition for Zero-Emission Buses in Denmark

Fuel Cell Electric Buses An attractive Value Proposition for Zero-Emission Buses In Denmark - April 2020 - Photo: An Attractive Line Bloch Value Klostergaard, Proposition North for Denmark Zero-Emission Region Buses. in Denmark Executive Summary Seeking alternatives to diesel buses are crucial for realizing the Danish zero Zero–Emission Fuel Cell emission reduction agenda in public transport by 2050. In Denmark alone, public transport and road-transport of cargo account for ap- proximately 25 per cent of the Danish CO2 emissions. Thus, the deployment of zero emission fuel cell electric buses (FCEBs) will be an important contribution Electric Buses for Denmark. to the Danish climate law committed to reaching 70 per cent below the CO2 emissions by 2030 and a total carbon neutrality by 2050. In line with the 2050 climate goals, Danish transit agencies and operators are being called to implement ways to improve air quality in their municipalities while maintaining quality of service. This can be achieved with the deployment of FCEBs and without compromising on range, route flexibility and operability. As a result, FCEBs are now also being included as one of the solutions in coming zero emission bus route tenders Denmark. Danish municipalities play an important role in establishing the public transport system of the future, however it is also essential that commercial players join forces to realize the deployment of zero-emission buses. In order to push the de- velopment forward, several leading players in the hydrogen fuel cell value chain have teamed up and formed the H2BusEurope consortium committed to support the FCEB infrastructure. -

Daf Introduces Lf 2016 Edition Lower Costs, Increased Efficiency

ISSUE 2 2015 IN ACTION DAF INTRODUCES LF 2016 EDITION LOWER COSTS, INCREASED EFFICIENCY DRIVEN BY QUALITY MAGAZINE OF DAF TRUCKS N.V. WWW.DAF.COM 2 SECTION GOOD BRAKING. BETTER DRIVING. INTARDER! Good braking means better driving. Better driving means driving more economically, safely, and more environmentally friendly. The ZF-Intarder hydrodynamic hydraulic brake allows for wear-free braking without fading, relieves the service brakes by up to 90 percent, and in doing so, reduces maintenance costs. Taking into account the vehicle’s entire service life, the Intarder offers a considerable savings potential ensuring quick amortization. In addition, the environment benefits from the reduced brake dust and noise emissions. Choose the ZF-Intarder for better performance on the road. www.zf.com/intarder IN ACTION 02 2015 IN THIS ISSUE: FOREWORD 3 4 DAF news A NEVER-ENDING RACE 6 Richard Zink: "Efficiency more Some two years after the Euro 6 emissions legislation came into important than ever" force, most people seem to have forgotten how much effort was expended by the truck industry to meet the requirements. 8 DAF LF 2016 Edition up to 5 percent It involved the development of new, state-of-the-art engine more fuel efficient technologies and of advanced exhaust after-treatment systems. These new technologies had a major impact on vehicle designs. DAF introduced a complete new generation of trucks: the Euro 6 LF, CF and XF. Never before was the degree of product innovation so large and never before production processes had to be changed so fundamentally. Understanding this, it is great to conclude that today we make the best trucks ever. -

Ventura – PS Shelfplate

Last Updated: 26/01/21 TDS PRODUCT IMAGE SHEET > VENTURA – PLUG SLIDER – DOOR MECHANISM & CONTROLS TDS Part Number Image OE Part Numbers & Description (WHERE FITTED) A155 A155 Ventura MICROSWITCH K5 PART OF A159/A160 (FITTED TO A159/A160) A159 A159 Ventura OBSTRUCTION DETECTION VALVE WRIGHTBUS GEMINI DD A160 Ventura WRIGHTBUS ECLIPSE SD + STREETCAR + A160 STREETLITE SD + NBFL DD, ADL E200 SD + OBSTRUCTION DETECTION VALVE E400 DD, PLAXTON PRESIDENT DD, EAST LANCS SD, OPTARE SD VERSA + TEMPO, MCV SD EVOLUTION, BLUEBIRD SD RS A358 A358 Ventura WRIGHTBUS GEMINI DD, POLISH PRESSURE SWITCH SCANIA OMNICITY DD A368 A368 Ventura MICROSWITCH HARTMANN WRIGHTBUS ECLIPSE SD + GEMINI DD + STREETCAR + STREETLITE SD + NBFL DD, # SECURING SCREW - B396 ADL E200 SD + E400 DD, PLAXTON PRESIDENT DD, EAST LANCS SD + OLYMPUS DD, OPTARE SD TEMPO + VERSA, MCV SD EVOLUTION, BLUEBIRD SD RS T – 01787 473000, F – 01787 477040 E - [email protected] Copyright © 2021 Transport Door Solutions Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Last Updated: 26/01/21 A517 A517 Ventura 5/2 VDMA 24VDC G1/8 WRIGHTBUS GEMINI DD A751 A751 Ventura T CONNECTOR DIA 4mm WRIGHTBUS PS2 A757 A757 Ventura RETAINING RING (BEARING HOUSING CARRIAGE) A760 A760 Ventura BOLT M6x16 ZP A775 A775 Ventura BOLT M10x20 ZP A925 A925 Ventura GUIDE ROLLER LR202 2RSR A976 A976 Ventura CONNECTOR DIN B WITH VARISTOR24 (WABCO SOLENOID) T – 01787 473000, F – 01787 477040 E - [email protected] Copyright © 2021 Transport Door Solutions Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Last Updated: 26/01/21 B158 FIT052B TDS FIT052B B158 Ventura ELBOW 6mm PUSHFIT x M5 B309 Ventura B309 PART OF F184 4/2 EMERGENCY VALVE M10x1 B310 B310 Ventura ROTARY GRIP FOR 4/2 EMERG. -

INTRODUCTION En Septembre 2020, Luca De Meo a Annoncé La Création

INTRODUCTION En septembre 2020, Luca De Meo a annoncé la création d’Alpine F1 Team en s’appuyant sur l’équipe du Groupe Renault, l’une des plus historiques et fructueuses de l’histoire de la Formule 1. Déjà reconnu pour ses records et succès en endurance et en rallye, le nom Alpine trouve naturellement sa place dans l’exigence, le prestige et la performance de la F1. La marque Alpine, symbole de sportivité, d’élégance et d’agilité, désignera le châssis et rendra hommage à l’expertise à l’origine de l’A110. Pour Alpine, il s’agit d’une étape clé pour accélérer le développement et le rayonnement de la marque. Le moteur de l’écurie continuera de bénéficier de l’expertise unique du Groupe Renault dans les motorisations hybrides, dont la dénomination Renault E-Tech sera conservée. Luca De Meo, directeur général du Groupe Renault : « C’est une véritable joie de voir le nom puissant et vibrant d’Alpine sur une Formule 1. De nouvelles couleurs, un nouvel encadrement, des projets ambitieux : il s’agit d’un nouveau départ, basé sur quarante ans d’histoire. Nous allierons les valeurs d’authenticité, d’élégance et d’audace d’Alpine à notre expertise en matière d’ingénierie et de châssis. C'est toute la beauté d'être constructeur en Formule 1. Nous affronterons les plus grands noms pour des courses spectaculaires faites et suivies par des passionnés enthousiastes. J’ai hâte que la saison commence. » Alpine aujourd’hui et demain Dans le cadre du plan stratégique « Renaulution » du Groupe Renault, Alpine a dévoilé ses projets à long terme pour positionner la marque à la pointe de l’innovation. -

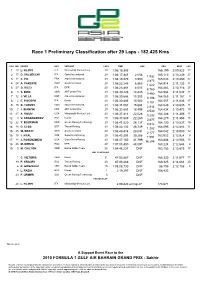

Race 1 Preliminary Classification After 29 Laps - 182.425 Kms

Race 1 Preliminary Classification after 29 Laps - 182.425 Kms POS NO DRIVER NAT ENTRANT LAPS TIME GAP KPH BEST LAP 1 20 L. FILIPPI ITA MalaysiaQi-Meritus.Com 29 1:06:15.383 165.199 2:09.823 27 2 17 D. VALSECCHI ITA iSport International 29 1:06:17.441 2.058 165.113 2:10.239 27 1.932 3 11 C. PIC FRA Arden International 29 1:06:19.373 3.990 165.033 2:10.450 27 2.873 4 24 A. PARENTE POR Scuderia Coloni 29 1:06:22.246 6.863 164.914 2:11.132 11 1.222 5 27 G. RICCI ITA DPR 29 1:06:23.468 8.085 164.863 2:10.716 27 6.760 6 8 S. BIRD GBR ART Grand Prix 29 1:06:30.228 14.845 164.584 2:11.032 11 0.460 7 12 J. VILLA ESP Arden International 29 1:06:30.688 15.305 164.565 2:11.167 9 0.198 8 2 E. PISCOPO ITA Dams 29 1:06:30.886 15.503 164.557 2:11.636 17 0.181 9 16 O. TURVEY GBR iSport International 29 1:06:31.067 15.684 164.549 2:10.605 11 2.814 10 7 J. BIANCHI FRA ART Grand Prix 29 1:06:33.881 18.498 164.434 2:10.472 10 3.530 11 21 A. ROSSI USA MalaysiaQi-Meritus.Com 29 1:06:37.411 22.028 164.288 2:11.396 11 0.232 12 3 V.