'Paris Today, Leeds Tomorrow!' Remembering 1968 in Leeds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MPS-0746712/1 the GUARDIAN 18.3.68 Police Repel Anti—War Mob

MPS-0746712/1 THE GUARDIAN 18.3.68 Police repel anti—war mob at US embassy BY OUR OWN REPORTERS Britain's biggest anti-Vietnam war demonstration ended in London yesterday with an estimated 300 arrests: 86 people were treated by the St John Ambulance Brigade for injuries and 50, including 25 policemen, one with serious spine injury, were taken to hospital. Demonstrators and police—mounted and on foot—engaged in a protracted battle, throwing stones, earth, firecrackers and smoke bombs. Plastic blood, an innovation, added a touch of vicarious brutality. It was only after considerable provocation that police tempers began to fray and truncheons were used, and then only for a short time. The demonstrators seemed determined to stay until they had provoked a violent response of some sort from the police. This intention became paramount once they entered Grosvenor Square. Mr Peter Jackson, Labour MP for High Peak, said last night that he would put down a question in the Commons today about "unnecessary violence by police." Earlier in the afternoon, members of the Monday Club, including two MPs, Mr Patrick Wall and Mr John Biggs- Davison, handed in letters expressing support to the United States and South Vietnamese embassies More than 1,000 police were waiting for the demonstrators in Grosvenor Square. They gathered in front of the embassy while diagonal lines stood shoulder to shoulder to cordon off the corners of the square closest to the building. About 10 coaches filled with constables waited in the space to rush wherever they were needed and a dozen mounted police rode into the square about a quarter of an hour before the demonstrators arrived. -

OIL and SANCTIONS the Times, London, May 9, 1966 The

SOUTHERN AFRICA NEWS BULLETIN Committee on Southern Africa, National Student Christian Federation, 475 Riverside Drive, New York, N. Y., 10027. Room 754. RHODESIA NEWS SUMv4ARY Weekof May 5 -ll EDITORIALS AND PERSONAL COMMEM The Economist - May 7, 1966 Letter to the Editor from Patrick Wall, House of Commons. "I wonder if your article "Talks about Talks" (April 30) has really struck the right balance. The implication is that Rhodesia's economy is being rapidly eroded by sanctions and that the South Africans are not prepared to offer them long-term support. As far as one can ascertain it would seem that Rhodesia's economy has remained remarkably buoyant after nearly sic months of sanctions. It is true that the policy of sanctions may have made Rhodesians more amenable to negotiations but surely this is also true of the British economy. The total cost of the Rhodes ian campaign in visibles and invisibles has been estimated at some 1200 million in a full year and it must now be clar to Mr. Wilson that whether he likes it or not the next step will be the imposition of mandatory sanctions by the United Nations not only on Rhodesia but also on Scuth Africa and the Portuguese territories. The first and major victim of this step would be the British economy--deprived of our third best trade partner the blow might be mortal. I believe that these factors together with the ,strongly expressed views of the Governor and the Chief Justice must be foremost in Mr. Wilson's mind and it is surely he, rather than Mr. -

By-Election Results: Revised November 2003 1987-92

Factsheet M12 House of Commons Information Office Members Series By-election results: Revised November 2003 1987-92 Contents There were 24 by-elections in the 1987 Summary 2 Parliament. Of these by-elections, eight resulted Notes 3 Tables 3 in a change in winning party compared with the Constituency results 9 1987 General Election. The Conservatives lost Contact information 20 seven seats of which four went to the Liberal Feedback form 21 Democrats and three to Labour. Twenty of the by- elections were caused by the death of the sitting Member of Parliament, while three were due to resignations. This Factsheet is available on the internet through: http://www.parliament.uk/factsheets November 2003 FS No.M12 Ed 3.1 ISSN 0144-4689 © Parliamentary Copyright (House of Commons) 2003 May be reproduced for purposes of private study or research without permission. Reproduction for sale or other commercial purposes not permitted. 2 By-election results: 1987-92 House of Commons Information Office Factsheet M12 Summary There were 24 by-elections in the 1987 Parliament. This introduction gives some of the key facts about the results. The tables on pages 4 to 9 summarise the results and pages 10 to 17 give results for each constituency. Eight seats changed hands in the 1987 Parliament at by-elections. The Conservatives lost four seats to Labour and three to the Liberal Democrats. Labour lost Glasgow, Govan to the SNP. The merger of the Liberal Party and Social Democratic Party took place in March 1988 with the party named the Social and Liberal Democrats. This was changed to Liberal Democrats in 1989. -

"No Return to 1961 in Rhodesia" (299)

SOUTHERN AFRICA NEWS BULLETIN Committee on Southern Africa, National Student Christian Federation, 475 Riverside Drive, New York, N.Y., 10027. Room 754 RHODESIA NEWS SUMMARY Week of June 16-22, 1966 EDITORIALS AND PERSONAL COMMENTS The Times, London - June 21 "The farmers are now thought to see that if a settlement is not reached soon they will have to abandon next year's crop (tobacco) after heavy losses on this year's. Their reaction will be the acid test. If they prefer to abandon tobacco for subsistence farming rather than press Mr. Smith to a compromise - which their friends in business already urge - then Britain and Africa generally must sit down to besiege Rhodesia until it is received, or the world concert on sanctions breaks down. Neither result is desirable in British or African interests. It is right therefore for the officials to work over every formula that embodies Britaints basic principles on African constitu tional advancement and African consent to the final settlement." Manchester Guardian Weekly - June 16 Edftorial:' "No return to 1961 in Rhodesia" Perhaps the talks have already turned into negotiations, and if so Mr. Wilson should explain what they are about. Three factors can be considered in turn: sanctions, relations with Zambia, and Britain's aims in the Salisbury talks. Last week the President of the Rhodesian Associated Chambers of Commerce warned that many firms were struggling for existence. Dwindling stocks, import licenses, and the exchange control have been taking their toll for weeks, but this is the first public statement from business. The government has clearly been disguising the effect of sanctions; the petrol entering the country has to be paid for. -

E-News for Somatosensory Rehabilitation Ronald Melzack’S Special Issue

e-News for Somatosensory Rehabilitation Ronald Melzack’s special issue Powered by : www.neuropain.ch Ronald MELZACK’s Special issue Canada Canada H MERSKEY M ZAFFRAN TL PACKHAM Israel M DEVOR USA CJ WOOLF United Kingdom Switzerland C McCABE A ROEDER Argentina Australia S FRIGERI GL MOSELEY Editorial Claude J SPICHER BSc OT p4 Foreword Ronald MELZACK OC, OQ, FRSC, PhD p5 1 Article Harold MERSKEY DM, FRCPC Canada p6 2 Article G Lorimer MOSELEY PhD, FACP Australia p7 3 Article Candida S McCABE PhD, RGN United-Kingdom p9 4 Article Clifford J WOOLF MB, BCh, PhD USA p11 5 Article Marshall DEVOR PhD Israel p12 6 Article Sandra B FRIGERI OT Argentina p17 7 Article Tara L PACKHAM MSc, OT Reg Ont Canada p18 8 Article Marc ZAFFRANMD Canada p19 9 Article Angie ROEDERPT Switzerland p20 1 e-News for Somatosensory Rehabilitation Ronald Melzack’s special issue France Belgium V SORIOT B MORLION USA Netherlands SW STRALKA RSGM PEREZ Switzerland P SPICHER United Kingdom M FITZGERALD Lebanon H ABU-SAAD HUIJER South Africa Brazil Spain TLB LE ROUX S de ANDRADE R GÁLVEZ L PRINGLE 10 Article Pascale SPICHER PhD Switzerland p22 11 Article Roberto SGM PEREZ PT, PhD Netherlands p25 12 Article Vincent SORIOTMD France p27 13 Article Theo LB LE ROUX MD South Africa p28 14 Article Maria FITZGERALD BA, PhD, FMedSci United-Kingdom p29 15 Article Bart MORLIONMD Belgium p31 16 Article Sibele de ANDRADE MELO PT, PhD Brazil p32 17 Article Lynne PRINGLE OT, BA Psych South Africa p33 18 Article Susan W STRALKA PT, DPT, MS USA p34 19 Article Rafael GÁLVEZ MD Spain p35 20 Article Huda ABU-SAAD HUIJER RN, PhD, FEANS, FAAN Lebanon p36 Powered by : www.NoSpe.ch 2 e-News for Somatosensory Rehabilitation Ronald Melzack’s special issue Ronald MELZACK’s Special issue chosen by Claude J. -

The NATO Parliamentary Assembly and UK Delegations

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 8951, 5 November 2020 The NATO Parliamentary By Nigel Walker Assembly and UK delegations Contents: 1. Summary 2. UK delegations 3. Appendix 1: Alphabetical list of UK delegates 1955-present www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The NATO Parliamentary Assembly and UK delegations Contents 1. Summary 3 1.1 NATO Parliamentary Assembly in brief 3 1.2 The UK Delegation 6 2. UK delegations 8 2.1 2019-2024 Parliament 9 2.2 2017-2019 Parliament 10 2.3 2015-2017 Parliament 11 2.4 2010-2015 Parliament 12 2.5 2005-2010 Parliament 13 2.6 2001-2005 Parliament 14 2.7 1997-2001 Parliament 15 2.8 1992-1997 Parliament 16 2.9 1987-1992 Parliament 17 2.10 1983-1987 Parliament 18 2.11 1979-1983 Parliament 19 2.12 Oct1974-1979 Parliament 20 2.13 Feb-Oct 1974 Parliament 21 2.14 1970- Feb1974 Parliament 22 2.15 1966-1970 Parliament 23 2.16 1964-1966 Parliament 24 2.17 1959-1964 Parliament 25 2.18 1955-1959 Parliament 26 3. Appendix 1: Alphabetical list of UK delegates 1955- present 28 Cover page image copyright: Image 15116584265_f2355b15bb_o, NATO Parliamentary Assembly Pre-Summit Conference in London, 2 September 2014 by Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) – Flickr home page. Licensed by Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license/ image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 5 November 2020 1. Summary Since being formed in 1965, the NATO Parliamentary Assembly has provided a forum for parliamentarians from the NATO Member States to promote debate on key security challenges, facilitate mutual understanding and support national parliamentary oversight of defence matters. -

Sources for Studying Politicians and Political Parties

Politicians and Political Parties A Guide to Materials at Hull History Centre Worship Street Hull, HU2 8BG Introduction Hull History Centre holds over 2000 collections which cover a huge range of subjects. Finding your way through this to identify material that interests you can be daunting. The following is a guide to materials held at Hull History Centre on the subject of Politicians and Political Parties. The guide is intended to aid the researcher in the identification of archival collections for use in research projects, dissertations and theses. Entries in this guide provide brief summaries of individual collection titles, covering dates, and content. More detailed descriptions of content can be found on the History Centre’s online catalogue, where you can also download PDF versions of individual catalogues. The online catalogue can be accessed at catalogue.historycentrecatalogue.org.uk. Materials listed in this guide are not exhaustive and so you should also use the History Centre’s online catalogue to search for terms specific to your research topic. The History Centre’s website contains further guides to our collections which might also be of use to researchers looking to identify resources. The website can be accessed at www.hullhistorycentre.org.uk. Should you require any further advice, this guide has been prepared by the Hull University Archives team who are happy to help in any way they can. Questions should be directed to HUA staff at [email protected] by marking enquiries ‘FAO HUA Archives Staff’ in the subject line. Hints and Tips In addition to the below collections, there may be other material relating to politicians and political parties amongst the holdings of Hull History Centre. -

Ull History Centre: U DPW

Hull History Centre: U DPW U DPW Records of Patrick Wall MP 1890-1992 Accession number: 1993/25 Historical Background/Biographical Background: Patrick Henry Bligh Wall was born in Cheshire on 19 October 1916, the son of Henry Benedict Wall and Gladys Eleanor Finney. He was educated at Downside School, Bath. In 1935 he was commissioned in the Royal Marines, training to become a specialist in naval gunnery. During the Second World War, he served on various Royal Navy vessels, including Iron Duke, Valiant and Malaya, between 1940 and 1943. From 1943 to 1945 he served in RN support craft, with the United States Navy and then with the Royal Marine Commandos. He was awarded both the Military Cross and the US Legion of Merit in 1945. After the war he studied at the Royal Naval Staff College and the Joint Services Staff College, and was a staff instructor at the School of Combined Operations between 1946 and 1948. His last appointment afloat was in HMS Vanguard in 1949. He retired as a Major in 1950 in order to concentrate on a political career. However he remained a Reservist, commanding 47 Commando, Royal Marine Forces Volunteer Reserve, from 1951 until its disbandment in 1956. He was awarded the Volunteer Reserve Decoration (VRD) in 1957. His involvement in naval affairs was continued for many years through his work with the City of Westminster Sea Scout and Sea Cadet organisations, and the London Sea Scout Committee. He contested the Cleveland constituency for the Conservative Party in the general election of 1951, and again at a bye-election the following year. -

The Chichester-Clarks Genet on Black Power Creedence Clearwater

The Chichester-Clarks Genet on Black Power B la c k Creedence Clearwater Vietnam / Trinidad/Cuba D w arf Jack Straw/Mao Established 1817 Vol 14 No 33 10th May 1970 Price 2/- The Black Dwarf 10th May 1970 Page 2 No Foreign Troops Tinfoil Tiger, in Trinidad! we go to press the U. S. and unreported, strikes grew in fre The Apollo 13 space mission should a whole it is just one more Television Guadalcanal, with 15 helicopters and quency. Above all, illegal activity in be the last for a very long time. show. It may bedazzle them, they .000 marines on board, is steaming creasingly forced the unions to These particular extravaganzas of may get sucked into the orgy of towards Trinidad. Two British the capitalist spectacle have already national tub-thumping that surrounds rigates, the Sirus and the Jupiter, become political organisations so consumed enough of the world’s re it, they may “itentify” with the and five other U. S. warships have much so that they now constitute a sources and technology. They have glamourised stars at the centre of it taken positions off the coast. The real extra-parliamentary political already sickened people enough with all. But they are not involved in it, ayana and Jamaican armies are opposition. As discontent among the their flag-waving ballyhoo and their they have not helped to create it, and r eady for action. Venezuelan workers has increased, the militant shoddy chauvinism. they are certainly not the ones who warships and planes have been unions have gained in strength. -

Notes to Chapter 1 1. I Have Used the Term 'Conservative Backbenchers

Notes Notes to Chapter 1 1. I have used the term 'Conservative backbenchers' to describe the entire Conservative party in opposition, and those behind the Treasury bench once Churchill returned to No. 10 Downing Street in October 1951. 2. Gilbert Longden (secretary) memorandum to Charles Mott-Radclyffe, chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee, Foreign Affairs Commit tee minutes, undated. 1.56. The Conservative Party Archives at the Bodleian Library, Oxford. 3. Lord Thorneycroft interview with author. 4. Sir Cranley Onslow MP, chairman of the 1922 Committee 1984-92, interview with author. 5. For an excellent discussion of the role of the Whips, see Philip Norton: Conservative Dissidents: Dissent within the Parliamentary Conservative Party 1970-74 (Maurice Temple Smith, London 1978), pp. 163-175. 6. The Whips' contact with backbenchers was three-fold: through the area whip, backbench committee whip and personal acquaintance. 7. The Chief Whip's Office. 8. Michael Dobbs: To Play The King (HarperCollins, London 1992). 9. Francis Pym, Chief Whip in Edward Heath's government (1970-74), quoted in Norton: Conservative Dissidents, p. 163. 10. See Donald Watt: Personalities and Policies: Studies in the Formulation of British Foreign Policy in the Twentieth Century (Longmans, London 1965), pp. 1-15. Personal affection for a fellow member, no matter how ex traordinary his professed views, was very often accompanied by a greater tolerance for an aberrant opinion; conversely, deep-seated dislike would encourage dismissal of an argument: Sir Reginald Bennett interview with author. 11. For detailed discussion of the political elite, see Michael Charlton: The Price of Victory BBC (London 1983). -

Patrick Wall, Julian Amery, and the Death and Afterlife of the British Empire

Nothing New Under the Setting Sun: Patrick Wall, Julian Amery, and the Death and Afterlife of the British Empire by Frank Fazio B.A. in History, May 2018, Villanova University A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 17, 2020 Thesis directed by Dane Kennedy Elmer Louis Kayser Professor of History Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................1 2. Castles Made of Sand: The Rise and Fall of the Central African Federation, 1950- 1963 .....................................................................................................................................7 3. “Wrapped Up in the Union Jack”: UDI and the Right-Wing Reaction, 1963-1980 ....32 4. Stoking the Embers of Empire: The Falklands and the Half-Life of Empire, 1968- ...57 5. Bibliography .....................................................................................................................77 ii Introduction After being swept out of Parliament in the winter of 1966, Julian Amery set about writing his memoirs. Son of a famous father and son-in-law of a former Prime Minister, the 47-year-old felt sure that this political setback was merely a bump in the road. Therefore, rather than risking offending his once and future peers by writing “with candour,” Amery chose to write his memoirs about his early life and service during the Second World War.1 True to his word, Amery concluded the first and only volume of his memoirs with his election to Parliament in 1950. However, his brief preface betrayed a crucial aspect of how he perceived Britain’s place in the world in the late 1960s. -

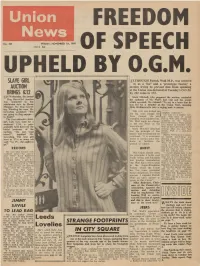

Union News Sent Its Own General Infirmary in His Spare Lovelies— You May Be the Both Sets of Prints Are in a When the Prints First Appeared

Union FREEDOM News ___FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 1st, 1968 OF SPEECH UPHELD BY O.G.M. SLAVE GIRL ALTHOUGH Patrick Wall M.P., was referred to as a ‘liar’ and a ‘prototype fascist/ a AUCTION motion trying to prevent him from speaking at the Union was defeated at Tuesday’s O.G.M. BRINGS £12 by 222 votes to 172. 0 N Wednesday, the annual Mark Mitchell, who proposed the motion, reminded Rag Slave-Girl Auction the audience of Mr. Wall’s last visit and the events was conducted in fine which occurred. He claimed: “To say in a letter that he rabelaisian style by House was led by a member of the Union Staff, meaning Manager, Mr. Reg Gravel Mike Hollingworth, into a raging mob is untrue. ing. Wielding his cane, Mr. “His wife was kicked on Graveling promised: “Pm complete hypocrite. ’ ’ not going to flog anyone— the leg, even though the Ina Ure, in a similar vein, to death!” Press claimed ‘she was said: “The kind of people The first attractive slave- trampled on in student riots. Patrick Wall calls friends are Mr. Wall made no attempt members of the National girl, Judy Lee, went for a Front Movement. These people moderate 12/6, a price to tell the Press of the have beaten up hecklers while probably he\d down by the inaccuracies.” Wall sat there grinning and did initial hesitancy of the Mark Mitchell admitted nothing. They also give Nazi that the principle of free salutes. Wall is a prototype auction. “Do you want Fascist.” blood?”, inquired Mr.