Towards a Cyberpragmatics of Mobile Instant Messaging Francisco Yus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

+1. Introduction 2. Cyrillic Letter Rumanian Yn

MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM +1. INTRODUCTION These are comments to "Additional Cyrillic Characters In Unicode: A Preliminary Proposal". I'm examining each section of that document, as well as adding some extra notes (marked "+" in titles). Below I use standard Russian Cyrillic characters; please be sure that you have appropriate fonts installed. If everything is OK, the following two lines must look similarly (encoding CP-1251): (sample Cyrillic letters) АабВЕеЗКкМНОопРрСсТуХхЧЬ (Latin letters and digits) Aa6BEe3KkMHOonPpCcTyXx4b 2. CYRILLIC LETTER RUMANIAN YN In the late Cyrillic semi-uncial Rumanian/Moldavian editions, the shape of YN was very similar to inverted PSI, see the following sample from the Ноул Тестамент (New Testament) of 1818, Neamt/Нямец, folio 542 v.: file:///Users/everson/Documents/Eudora%20Folder/Attachments%20Folder/Addons/MAIN.HTM Page 1 of 28 MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM Here you can see YN and PSI in both upper- and lowercase forms. Note that the upper part of YN is not a sharp arrowhead, but something horizontally cut even with kind of serif (in the uppercase form). Thus, the shape of the letter in modern-style fonts (like Times or Arial) may look somewhat similar to Cyrillic "Л"/"л" with the central vertical stem looking like in lowercase "ф" drawn from the middle of upper horizontal line downwards, with regular serif at the bottom (horizontal, not slanted): Compare also with the proposed shape of PSI (Section 36). 3. CYRILLIC LETTER IOTIFIED A file:///Users/everson/Documents/Eudora%20Folder/Attachments%20Folder/Addons/MAIN.HTM Page 2 of 28 MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM I support the idea that "IA" must be separated from "Я". -

From Heraldry to History: the Death of Giles D'argentan Andrew Taylor

From Heraldry to History: The Death of Giles D’Argentan Andrew Taylor John Barbour’s sources for the Bruce have always attracted much discussion. This essay considers the contribution of heraldic narrative, whether written or oral, focus- ing on the example of Giles D’Argentan. It concludes that such narratives may indeed be more significant for the Bruce and other chivalric romances than previously thought. Keywords: Giles D’Argentan; Bannockburn; John Barbour; Walter Bower; Bruce; Edward Bruce; chivalry; Edward II; Jean Froissart; Thomas Gray; Gib Harper; heralds; heraldic narrative; Otterburn; Robert le Roy; Scalachronica; Scotichronicon. At a certain point, neither family pride, nor loyalty to one’s comrades or king, nor years of indoctrination in chivalric values can withstand the basic human instinct to escape danger, and once the first man flees the others soon follow. So it was at Bannockburn. After several hours, the battle turned against the English. According to John Barbour’s account in his Bruce, when King Edward saw that the enemy’s army had grown so brave that his own men lacked the strength to withstand and had begun to flee, he himself was so greatly discouraged (“abaysyt sa gretumly”) that he and five hundred of his men took to flight in a great rush (“in-till a frusch”) (McDiarmid and Stevenson 1981: 3: 61; further references to Barbour’s Bruce will be to this edition, and will take the form of book and line numbers). Barbour adds, in fairness, that he has heard some men say that the king was led away against his will, before turning to one man who refused to withdraw: And quhen Schyr Gylis ye Argente Saw ye king yus and his mene Schap yaim to fley sa spedyly, He come rycht to ye king in hy And said “Schyr, sen it is sua Yat e yusgat our gat will ga Hawys gud day for agayne will I, eyt fled I neuer sekyrly And I cheys her to bid and dey Yan for to lyve schamly and fley”. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION 1. Prologue ............................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 The Present Study and its Historical Context .............................................................................. 7 1.2 Previous Studies and a Note on the Methodological Approach .................................................. 9 2. Hegemony and Patronage: Strategies of Survival and Expansion ................................................... 10 3. The Gung thang dkar chag: Its Sources and the Structure of the Present Book ............................. 13 4. sKyid-shod – A Key District of Northern Central Tibet. A Brief Historico-Geographical Delimitation ............................................................................. 17 4.1 Tshal-pa District in Narrow and Wider Perspectives ................................................................ 25 5. Historical Background ..................................................................................................................... 26 5.1 The Religious Communities in Northern Central Tibet in the 11th and 12th Centuries .............. 26 5.2 Rulers of the lHa-sa Valley in the Pre-Tshal-pa Period ............................................................ 27 6. Gung-thang Bla-ma Zhang: Yogi, Warlord and Monastic Founder ............................................... -

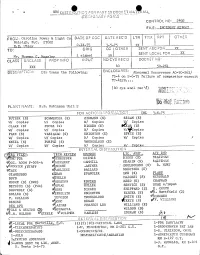

H. B. Robinson, Unit 2, Failure of Comparator Circuit TC-412B

NRC DISTRIJTIO2 FOR PART 50 DOCKET MATLrIAL (TE,7.'RARY F OR'1 CONTROL NO:_ 2492 FILE: INCIIEL T121 FROM: Carolina Power & Light Co DATE OF DOC DATE D [WX RPT OTH Raleigh, N.C. 27602 E.E. Utley 2-14-75 __ TO: ORIG CC I OTHER SENT ECPDR XX Mr. Norman C. Moseley signed CLASS UN'JCLASS PROP !NFO 1NPUT NO CYS REIPC'D DOCUTT I II _ _ _o 50-261 DESCRIPTION: Ltr trans the following: ENCLOSURES: Abnormal Occurrence AQ-50-261/ 75-4 on 2-6-75 failure of comparator curcuit TC-412B.... (40 cys encl rec'd ' PLANT NAME: H.B. Robinson Unit 2 OAC2FOR ORMATI 3-67.5 BUTLER (S) SCHWENCER (S) ZiEMANN (S) REGAN (E) W/ Copies WI/ Copies W/ Copies Copies CLARK (S) STOLZ (S) DICKER (E) (S) W/ Copies W/ Copies W/ Copies W/Yopies PARR (S) VASSALLO (S) KNIGHTON (E) SPEIS (S) W/ copies W/ Copies W/ Copies WI Copies KNIEL (S) PURPLE (S) YOUNGBLOOD (E) W/ Copies W/ Copies 14 Copies W/ opies INTERNAL DIST; 1UTION F1 TECH REVIEW DENTON LIC. ASST. A/T IND BRAITMAN P1R ChREDER GRIMES DIGGS (S) (S) SALTZMAN OkGC, ROOM P-506-A 0IACCARRY GAMMILL GEARIN VuGOSSICK /STAFF 4NIGHT .ASTNER GOULBOURNE (S) B. HURT WASE 4AWLICKI BALLARD KREUTZER (E) PLANS GIAMBUSSO dBAOL SPANGLER LEE (S) BOYD 0TELID MAIGRET (S) MCDONALD CHAPMAN MOORE (S) (BWR) dkOUSTON ENVIRO REED (E) DEYOUNG (S) (PWR) ( OVAK MULLER SERVICE (S) DUBE w/input E. COUPE SKOVHOLT (S) C&OSS DICKER SHEPPARD (5) OfR. Hartfield (2) GOLLER (S) 01PPOLITO KNIGHTON SLATER (E) (S) OKLECKER P. -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

Run Date: 08/30/21 12Th District Court Page

RUN DATE: 09/27/21 12TH DISTRICT COURT PAGE: 1 312 S. JACKSON STREET JACKSON MI 49201 OUTSTANDING WARRANTS DATE STATUS -WRNT WARRANT DT NAME CUR CHARGE C/M/F DOB 5/15/2018 ABBAS MIAN/ZAHEE OVER CMV V C 1/01/1961 9/03/2021 ABBEY STEVEN/JOH TEL/HARASS M 7/09/1990 9/11/2020 ABBOTT JESSICA/MA CS USE NAR M 3/03/1983 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DIST. PEAC M 11/04/1998 12/04/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA HOME INV 2 F 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA DRUG PARAP M 11/04/1998 11/06/2020 ABDULLAH ASANI/HASA TRESPASSIN M 11/04/1998 10/20/2017 ABERNATHY DAMIAN/DEN CITYDOMEST M 1/23/1990 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT SPD 1-5 OV C 8/23/1993 8/23/2021 ABREGO JAIME/SANT IMPR PLATE M 8/23/1993 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI NO PROOF I C 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI SUSPEND OP M 9/06/1968 8/04/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI OPERATING M 9/06/1968 2/16/2021 ABSTON CHERICE/KI REGISTRATI C 9/06/1968 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA DRUGPARAPH M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OPERATING M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA USE MARIJ M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA OWPD M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA IMPR PLATE M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SEAT BELT C 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON TYLER/RENA SUSPEND OP M 7/16/1988 8/09/2021 ABSTON -

Sangs Rgyas Gling Pa (1341-1396) & His Longevity Teachings∗

192 正觀第六十三期/二Ο一二年十二月二十五日 Sangs rgyas gling pa (1341-1396) understanding on how Amit@bha has gained his central position in the & His Longevity Teachings∗ display of Five Buddha Families. Mei, Ching Hsuan Dharma Drum Buddhist College, Assistant Professor Keywords: longevity teachings, treasure revealer, treasure texts, biography, Amit@bha Abstract The development of Amit@bha tradition in medieval Tibet is an unsolved problem in the academic world, which definitely involved in complicated transmissions and confluence of different practices; therefore, need to be clarified through various aspects and approaches. In my previous studies of 'pho ba liturgy developed in medieval Tibet, I suggest that Sangs rgyas gling pa’s (1341-1396) revealed work of 'pho ba could be one of the important sources that integrates Amit@bha worship into consciousness transferring ('pho ba) practices. Furthermore, I notice that relevant teachings such as longevity (tshe sgrub) might also stimulate the formation of Amit@bha tradition. Yet Sangs rgyas gling pa and his discovered works are hardly highlighted. In this short essay, I will firstly focus on his biography in order to unveil his life story, his discoveries and transmissions. Secondly I will study his longevity teaching so as to demonstrate its close association to the worship of Amit@bha. It will help our ∗ 2012/6/9 收稿,2012/7/8 通過審查。 Sangs rgyas gling pa (1341-1396) & His Longevity Teachings 193 194 正觀第六十三期/二Ο一二年十二月二十五日 1. Biography of Sangs rgyas gling pa Furthermore, I notice that relevant teachings such as longevity (tshe sgrub)5 might also stimulate the formation of Amit@bha tradition. In my preliminary study, I explored three rNying ma pa masters Yet Sangs rgyas gling pa and his discovered works are hardly 1 who produced the instructions of 'pho ba in their work. -

Hollins University

HOLLINS Instructor: Sampon-Nicolas, Annette V E R S I T Y FREN 271 (1): French Culture & Civilization # of Students: 3 Student Academic Opinion Survey (SAGS) Term Spring-Term 2018 Date Instructions: For each numbered question, please check the bo beside the alternative which most closely approximates your opinion. There is space at the bottom of the page in which you may further represent your opinions about this course. 1. My overall rating of the instructor £3! Very good. Good Adequate Poor Very poor 2. My rating of the instructor s Very good Good Adequate Poor Very poor effectiveness 3. The instructor s attitude toward ffl Very positive Positive Neutral Negative Negative the students 4. My attitude toward the instructor Very positive Positive Neutral Negative Very negative 5. My interest in the subject H Very much Increased Not changed Decreased Very much increased decreased 6. Stimulation of my thinking m Very high High Moderate Low Very low 7. Contribution to my education li Very high High Moderate Low Very low 8. Difficulty level of the course Very difficult ED Difficult Average Easy Very easy 9. Fairness and adequacy of the 4 Very good Good Satisfactory Poor Very poor evaluation of my work 10. Amount of time I spent on Very high High Moderate Low Very low this course 11. My overall rating of the course £a Very good Good Adequate Poor Very poor Your maj or? C /M CM ?\ Your approximate cumulative grade-point average? is Your class level? ' dV y Grade you expect to receive in this course? iX Comments:-Ik ,W. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

Cyrillic # Version Number

############################################################### # # TLD: xn--j1aef # Script: Cyrillic # Version Number: 1.0 # Effective Date: July 1st, 2011 # Registry: Verisign, Inc. # Address: 12061 Bluemont Way, Reston VA 20190, USA # Telephone: +1 (703) 925-6999 # Email: [email protected] # URL: http://www.verisigninc.com # ############################################################### ############################################################### # # Codepoints allowed from the Cyrillic script. # ############################################################### U+0430 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER A U+0431 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER BE U+0432 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER VE U+0433 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER GE U+0434 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DE U+0435 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER IE U+0436 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZHE U+0437 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZE U+0438 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER II U+0439 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHORT II U+043A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KA U+043B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EL U+043C # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EM U+043D # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EN U+043E # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER O U+043F # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER PE U+0440 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ER U+0441 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ES U+0442 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TE U+0443 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER U U+0444 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EF U+0445 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KHA U+0446 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TSE U+0447 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER CHE U+0448 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHA U+0449 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHCHA U+044A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER HARD SIGN U+044B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER YERI U+044C # CYRILLIC -

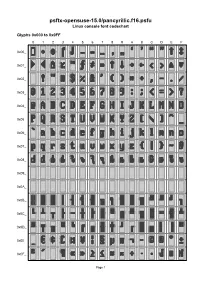

Psftx-Opensuse-15.0/Pancyrillic.F16.Psfu Linux Console Font Codechart

psftx-opensuse-15.0/pancyrillic.f16.psfu Linux console font codechart Glyphs 0x000 to 0x0FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x00_ 0x01_ 0x02_ 0x03_ 0x04_ 0x05_ 0x06_ 0x07_ 0x08_ 0x09_ 0x0A_ 0x0B_ 0x0C_ 0x0D_ 0x0E_ 0x0F_ Page 1 Glyphs 0x100 to 0x1FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x10_ 0x11_ 0x12_ 0x13_ 0x14_ 0x15_ 0x16_ 0x17_ 0x18_ 0x19_ 0x1A_ 0x1B_ 0x1C_ 0x1D_ 0x1E_ 0x1F_ Page 2 Font information 0x017 U+221E INFINITY Filename: psftx-opensuse-15.0/pancyrillic.f16.p 0x018 U+2191 UPWARDS ARROW sfu PSF version: 1 0x019 U+2193 DOWNWARDS ARROW Glyph size: 8 × 16 pixels 0x01A U+2192 RIGHTWARDS ARROW Glyph count: 512 Unicode font: Yes (mapping table present) 0x01B U+2190 LEFTWARDS ARROW 0x01C U+2039 SINGLE LEFT-POINTING Unicode mappings ANGLE QUOTATION MARK 0x000 U+FFFD REPLACEMENT 0x01D U+2040 CHARACTER TIE CHARACTER 0x01E U+25B2 BLACK UP-POINTING 0x001 U+2022 BULLET TRIANGLE 0x002 U+25C6 BLACK DIAMOND, 0x01F U+25BC BLACK DOWN-POINTING U+2666 BLACK DIAMOND SUIT TRIANGLE 0x003 U+2320 TOP HALF INTEGRAL 0x020 U+0020 SPACE 0x004 U+2321 BOTTOM HALF INTEGRAL 0x021 U+0021 EXCLAMATION MARK 0x005 U+2013 EN DASH 0x022 U+0022 QUOTATION MARK 0x006 U+2014 EM DASH 0x023 U+0023 NUMBER SIGN 0x007 U+2026 HORIZONTAL ELLIPSIS 0x024 U+0024 DOLLAR SIGN 0x008 U+201A SINGLE LOW-9 QUOTATION 0x025 U+0025 PERCENT SIGN MARK 0x026 U+0026 AMPERSAND 0x009 U+201E DOUBLE LOW-9 QUOTATION MARK 0x027 U+0027 APOSTROPHE 0x00A U+2018 LEFT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x028 U+0028 LEFT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x00B U+2019 RIGHT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x029 U+0029 RIGHT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x02A U+002A ASTERISK