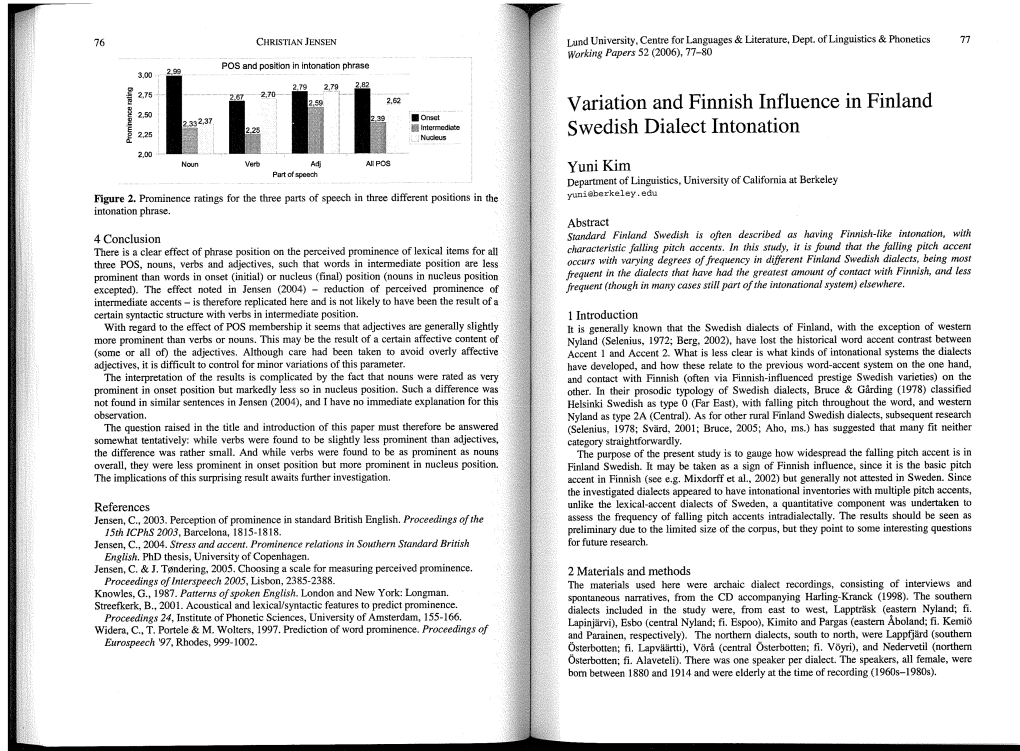

Variation and Finnish Influence in Finland Onset Intermediate Swedish Dialect Intonation Nucleus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Legislation and Identity in Finland Fennoswedes, the Saami and Signers in Finland’S Society

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI Language Legislation and Identity in Finland Fennoswedes, the Saami and Signers in Finland’s Society Anna Hirvonen 24.4.2017 University of Helsinki Faculty of Law Public International Law Master’s Thesis Advisor: Sahib Singh April 2017 Tiedekunta/Osasto Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos/Institution– Department Oikeustieteellinen Helsingin yliopisto Tekijä/Författare – Author Anna Inkeri Hirvonen Työn nimi / Arbetets titel – Title Language Legislation and Identity in Finland: Fennoswedes, the Saami and Signers in Finland’s Society Oppiaine /Läroämne – Subject Public International Law Työn laji/Arbetets art – Level Aika/Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä/ Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro-Gradu Huhtikuu 2017 74 Tiivistelmä/Referat – Abstract Finland is known for its language legislation which deals with the right to use one’s own language in courts and with public officials. In order to examine just how well the right to use one’s own language actually manifests in Finnish society, I examined the developments of language related rights internationally and in Europe and how those developments manifested in Finland. I also went over Finland’s linguistic history, seeing the developments that have lead us to today when Finland has three separate language act to deal with three different language situations. I analyzed the relevant legislations and by examining the latest language barometer studies, I wanted to find out what the real situation of these language and their identities are. I was also interested in the overall linguistic situation in Finland, which is affected by rising xenophobia and the issues surrounding the ILO 169. -

Swedish-Speaking Population As an Ethnic Group in Finland

SWEDISH-SPEAKING POPULATION AS AN ETHNIC GROUP IN FINLAND Elli Karjalainen" POVZETEK ŠVEDSKO GOVOREČE PREBIVALSTVO KOT ETNIČNA SKUPNOST NA FINSKEM Prispevek obravnava švedsko govoreče prebivalstvo na Finskem, ki izkazuje kot manjši- na, sebi lastne zakonitosti v rasti, populacijski strukturi in geografski razporeditvi. Obra- vnava tudi učinke mešanih zakonov in vključuje tudi vedno aktualne razprave o uporabi finskega jezika na Finskem. Tako v absolutnem kot relativnem smislu upadata število in delež švedskega prebi- valstva na Finskem. Zadnji dostopni podatki govore o 296 840 prebivalcih oziroma 6% deležu Švedov v skupnem številu Finske narodnosti. Švedska poselitev je nadpovprečno zgoščena na jugu in zahodu države. Stalen upad števila članov švedske narodnostne skup- nosti gre pripisati emigraciji, internim migracijskim tokovom, mešanim zakonom in upadu fertilnosti prebivalstva. Tudi starostna struktura švedskega prebivalstva ne govori v prid lastni reprodukciji. Odločilnega pomena je tudi, da so pripadniki švedske narodnosti v povprečju bolj izobraženi kot Finci. Pred kratkim seje zastavilo vprašanje ali je potrebno v finskih šolah ohranjati švedščino kot obvezen učni predmet. Introduction Finland is a bilingual country, with Finnish and Swedish as the official languages of the republic. The Swedish-speaking population is defined as Finnish citizens who live in Finland and speak Swedish as their mother tongue, 'mothertongue' regarded as the language of which the person in question has the best command. Children still too young to speak are registered according to the native tongue of their parents, principally of the mother (Fougstedt 1981: 22). Finland's Swedish-speaking population is here discussed as a minority group: what kind of a population group they form, and how this group differs in population structure from the total population. -

District 107 A.Pdf

Club Health Assessment for District 107 A through May 2016 Status Membership Reports LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice No Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Active Activity Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Email ** Report *** Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no report When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater in 3 more than of officers that in 12 within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not have months two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active appears in in brackets in red in red red red indicated Email red Clubs less than two years old 125168 LIETO/ILMATAR 06/19/2015 Active 19 0 16 -16 -45.71% 0 0 0 0 Clubs more than two years old 119850 ÅBO/SKOLAN 06/27/2013 Active 20 1 2 -1 -4.76% 21 2 0 1 59671 ÅLAND/FREJA 06/03/1997 Active 31 2 4 -2 -6.06% 33 11 1 0 41195 ÅLAND/SÖDRA 04/14/1982 Active 30 2 1 1 3.45% 29 34 0 0 20334 AURA 11/07/1968 Active 38 2 1 1 2.70% 37 24 0 4 $536.59 98864 AURA/SISU 03/22/2007 Active 21 2 1 1 5.00% 22 3 0 0 50840 BRÄNDÖ-KUMLINGE 07/03/1990 Active 14 0 0 0 0.00% 14 0 0 32231 DRAGSFJÄRD 05/05/1976 Active 22 0 4 -4 -15.38% 26 15 0 13 20373 HALIKKO/RIKALA 11/06/1958 Active 31 1 1 0 0.00% 31 3 0 0 20339 KAARINA 02/21/1966 Active 39 1 1 0 0.00% 39 15 0 0 32233 KAARINA/CITY 05/05/1976 Active 25 0 5 -5 -16.67% -

Language Perceptions and Practices in Multilingual Universities

Language Perceptions and Practices in Multilingual Universities Edited by Maria Kuteeva Kathrin Kaufhold Niina Hynninen Language Perceptions and Practices in Multilingual Universities Maria Kuteeva Kathrin Kaufhold • Niina Hynninen Editors Language Perceptions and Practices in Multilingual Universities Editors Maria Kuteeva Kathrin Kaufhold Department of English Department of English Stockholm University Stockholm University Stockholm, Sweden Stockholm, Sweden Niina Hynninen Department of Languages University of Helsinki Helsinki, Finland ISBN 978-3-030-38754-9 ISBN 978-3-030-38755-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38755-6 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

THE SWEDISH LANGUAGE Sharingsweden.Se PHOTO: CECILIA LARSSON LANTZ/IMAGEBANK.SWEDEN.SE

FACTS ABOUT SWEDEN / THE SWEDISH LANGUAGE sharingsweden.se PHOTO: CECILIA LARSSON LANTZ/IMAGEBANK.SWEDEN.SE PHOTO: THE SWEDISH LANGUAGE Sweden is a multilingual country. However, Swedish is and has always been the majority language and the country’s main language. Here, Catharina Grünbaum paints a picture of the language from Viking times to the present day: its development, its peculiarities and its status. The national language of Sweden is Despite the dominant status of Swedish, Swedish and related languages Swedish. It is the mother tongue of Sweden is not a monolingual country. Swedish is a Nordic language, a Ger- approximately 8 million of the country’s The Sami in the north have always been manic branch of the Indo-European total population of almost 10 million. a domestic minority, and the country language tree. Danish and Norwegian Swedish is also spoken by around has had a Finnish-speaking population are its siblings, while the other Nordic 300,000 Finland Swedes, 25,000 of ever since the Middle Ages. Finnish languages, Icelandic and Faroese, are whom live on the Swedish-speaking and Meänkieli (a Finnish dialect spoken more like half-siblings that have pre- Åland islands. in the Torne river valley in northern served more of their original features. Swedish is one of the two national Sweden), spoken by a total of approxi- Using this approach, English and languages of Finland, along with Finnish, mately 250,000 people in Sweden, German are almost cousins. for historical reasons. Finland was part and Sami all have legal status as The relationship with other Indo- of Sweden until 1809. -

The Finnish Archipelago Coast from AD 500 to 1550 – a Zone of Interaction

The Finnish Archipelago Coast from AD 500 to 1550 – a Zone of Interaction Tapani Tuovinen [email protected], [email protected] Abstract New archaeological, historical, paleoecological and onomastic evidence indicates Iron Age settle- ment on the archipelago coast of Uusimaa, a region which traditionally has been perceived as deso- lated during the Iron Age. This view, which has pertained to large parts of the archipelago coast, can be traced back to the early period of field archaeology, when an initial conception of the archipelago as an unsettled and insignificant territory took form. Over time, the idea has been rendered possible by the unbalance between the archaeological evidence and the written sources, the predominant trend of archaeology towards the mainland (the terrestrical paradigm), and the history culture of wilderness. Wilderness was an important platform for the nationalistic constructions of early Finnishness. The thesis about the Iron Age archipelago as an untouched no-man’s land was a history politically convenient tacit agreement between the Finnish- and the Swedish-minded scholars. It can be seen as a part of the post-war demand for a common view of history. A geographical model of the present-day archaeological, historical and palaeoecological evi- dence of the archipelago coast is suggested. Keywords: Finland, Iron Age, Middle Ages, archipelago, settlement studies, nationalism, history, culture, wilderness, borderlands. 1. The coastal Uusimaa revisited er the country had inhabitants at all during the Bronze Age (Aspelin 1875: 58). This drastic The early Finnish settlement archaeologists of- interpretation developed into a long-term re- ten treated the question of whether the country search tradition that contains the idea of easily was settled at all during the prehistory: were perishable human communities and abandoned people in some sense active there, or was the regions. -

Webometric Network Analysis

Webometric Network Analysis Webometric Network Analysis Mapping Cooperation and Geopolitical Connections between Local Government Administration on the Web Kim Holmberg ÅBO 2009 ÅBO AKADEMIS FÖRLAG – ÅBO AKADEMI UNIVERSITY PRESS CIP Cataloguing in Publication Holmberg , Kim Webometric network analysis : mapping cooperation and geopolitical connections between local government administration on the web / Kim Holmberg. – Åbo : Åbo Akademi University Press, 2009. Diss.: Åbo Akademi University. ISBN 978-951-765-510-1 ISBN 978-951-765-510-1 ISBN 978-951-765-511-8 (digital) Painosalama Oy Åbo 2009 Acknowledgements This research started as a mixed collection of very diffuse ideas that gradually gained focus and evolved into the research that now has been completed and written down. Without the advice and encouragement of certain persons this work would not have been possible, or at least it would have looked very different. To these persons I direct my deep gratitude. First of all I want to thank my supervisors, professors Gunilla Widén-Wulff and Mike Thelwall, for their advice and support throughout this process. I have been very fortunate to have two such knowledgeable and generous supervisors. Gunilla has given me the freedom to pursue my own path and make my own discoveries, but she has always been there to help me find my way back to the path when I have strayed too far from it. It has been a great privilege to have Mike as my second supervisor. Mike’s vast knowledge and experience of webometrics, great technical skills, and unparalleled helpfulness have been extremely valuable throughout this research. I also want to thank professors Mariam Ginman and Sara von Ungern-Sternberg for convincing me to pursue a doctoral degree, a decision that I have never regretted. -

University of Groningen an Acoustic Analysis of Vowel Pronunciation In

University of Groningen An Acoustic Analysis of Vowel Pronunciation in Swedish Dialects Leinonen, Therese IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2010 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Leinonen, T. (2010). An Acoustic Analysis of Vowel Pronunciation in Swedish Dialects. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 01-10-2021 Chapter 2 Background In this chapter the linguistic and theoretical background for the thesis is presented. -

Bredbandsinfo Korpoström 6.9.2007

Kaj Söderman Development Manager Archipelago Networks LTD ‐ ‐ Region Åboland r.f. Turku Helsinki The ARCHIPELAGO 11.5.2009 Kaj Söderman, SGNet Skärgårdsnäten AB 11.5.2009 Kaj Söderman, SGNet Some Facts…. y 22.500 inhabitants y 19.000 islands and islets y 12.000 cottages and summer residences y 37 ferries, bigger and smaller y Bi‐lingual (finnish and swedish) y 8 municipalities merged to 2, Västaboland and Kimitoön. 11.5.2009 Kaj Söderman, SGNet Long distances Examples of distances: Houtskär - Korpo: 1h 15 min Compare: Roma - L’Aquila Houtskär - Pargas: 2 h 15 min Compare: Roma - Napoli Iniö - Houtskär : 4 h 30 min Compare : Roma - Parma Utö - Pargas : 6 h 20 min Compare : Roma - Trieste Iniö - Utö: 8 t 20 min Compare : San Remo – Napoli (849km) 11.5.2009 Kaj Söderman, SGNet Archipelago Networks LTD y Fully owned by Region Aboland and the municipalities y Builds and maintains the core network y Network operator y Develops and tests new services 11.5.2009 Kaj Söderman, SGNet Video telephone for alone living elderly people in Turku Archipelago Innovative actions programme funded by European Regional Development Fund ERDF ArchipelagoELLI y This project aimed to give senior citizens in rural areas, possibility to live at home as long as possible with interactive contact‐tool. y The tool was a videophone with high‐resolution display and good audio. y It functioned trough Internet, and required at least DSL‐ connection at the customers (senior) premises. y These phones were connected to a regional network containing 21‐similar phones placed out to seniors, Health centers (responsible district or community health nurse, doctors) and relatives. -

Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue?

Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community KARIN ARVIDSSON Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community NORD: 2012:008 ISBN: 978-92-893-2404-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/Nord2012-008 Author: Karin Arvidsson Editor: Jesper Schou-Knudsen Research and editing: Arvidsson Kultur & Kommunikation AB Translation: Leslie Walke (Translation of Bodil Aurstad’s article by Anne-Margaret Bressendorff) Photography: Johannes Jansson (Photo of Fredrik Lindström by Magnus Fröderberg) Design: Mar Mar Co. Print: Scanprint A/S, Viby Edition of 1000 Printed in Denmark Nordic Council Nordic Council of Ministers Ved Stranden 18 Ved Stranden 18 DK-1061 Copenhagen K DK-1061 Copenhagen K Phone (+45) 3396 0200 Phone (+45) 3396 0400 www.norden.org The Nordic Co-operation Nordic co-operation is one of the world’s most extensive forms of regional collaboration, involving Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. Nordic co-operation has firm traditions in politics, the economy, and culture. It plays an important role in European and international collaboration, and aims at creating a strong Nordic community in a strong Europe. Nordic co-operation seeks to safeguard Nordic and regional interests and principles in the global community. Common Nordic values help the region solidify its position as one of the world’s most innovative and competitive. Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community KARIN ARVIDSSON Preface Languages in the Nordic Region 13 Fredrik Lindström Language researcher, comedian and and presenter on Swedish television. -

12359947.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Julkari Stakes Sosiaali- ja terveysalan tutkimus- ja kehittämiskeskus Suomen virallinen tilasto Sosiaaliturva 2007 Forsknings- och utvecklingscentralen för social- och hälsovården Finlands officiella statistik Socialskydd Official Statistics of Finland National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health Social Protection Ikääntyneiden sosiaali- ja terveyspalvelut 2005 Äldreomsorgen 2005 Care and Services for Older People 2005 Tiedustelut – Förfrågningar – For further information Suomen virallinen tilasto Sari Kauppinen (09) 3967 2373 Finlands officiella statistik Official Statistics of Finland Toimitusneuvosto – Redoktionsråd – Editorial board Olli Nylander, puheenjohtaja – ordförande – chairman Päivi Hauhia Sari Kauppinen Irma-Leena Notkola Matti Ojala Hannu Rintanen Pirjo Tuomola Ari Virtanen Sirkka Kiuru, sihteeri – sekreterare – secretary © Stakes Kansi – Omslag – Cover design: Harri Heikkilä Taitto – Lay-out: Christine Strid ISBN 978-951-33-1181-0 ISSN 1795-5165 (Suomen virallinen tilasto) ISSN 1459-7071 (Ikääntyneiden sosiaali- ja terveyspalvelut) Yliopistopaino Helsinki 2007 Ikääntyneiden sosiaali- ja terveyspalvelut 2005 – Äldreomsorgen 2005 – Care and Services for Older People 2005 Lukijalle Ikääntyneiden sosiaali- ja terveyspalvelut 2005 -julkaisuun on koottu keskeiset tilastotiedot ikääntyneiden sosiaali- ja terveys- palveluista ja niiden kehityksestä. Julkaisussa on tietoa palvelujen käytöstä, asiakasrakenteesta, henkilöstöstä -

Dialekt Där Den Nästan Inte Finns En Folklingvistisk Studie Av Dialektens Sociala Betydelse I Ett Standardspråksnära Område

SKRIFTER UTGIVNA AV INSTITUTIONEN FÖR NORDISKA SPRÅK VID UPPSALA UNIVERSITET 98 JANNIE TEINLER Dialekt där den nästan inte finns En folklingvistisk studie av dialektens sociala betydelse i ett standardspråksnära område With a summary: Dialect where it almost doesn’t exist: A folk linguistic study of the social meaning of a dialect close to the standard language 2016 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Ihresalen, Engelska parken, Thunbergsvägen 3L, Uppsala, Saturday, 12 November 2016 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in Swedish. Faculty examiner: Rune Røsstad (Universitetet i Agder, Institutt for nordisk og mediefag). Abstract Teinler, J. 2016. Dialekt där den nästan inte finns. En folklingvistisk studie av dialektens sociala betydelse i ett standardspråksnära område. (Dialect where it almost doesn’t exist. A folk linguistic study of the social meaning of a dialect close to the standard language). Skrifter utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet 98. 295 pp. Uppsala: Institutionen för nordiska språk. ISBN 978-91-506-2597-4. By approaching dialect and standard language from a folk linguistic perspective, this thesis aims to investigate how laypeople perceive, talk about and orient towards dialect and standard language in a dialect area close to the perceived linguistic and administrative centre of Sweden. It consequently focuses on dialect and standard language as socially meaningful entities, rather than as sets of linguistic features, and studies a dialect area as it is understood by those who identify with it. To explore these issues, group interviews, a set of quantitative tests among adolescents and a ‘mental mapping’ task were used.