Journal of European Integration History Revue D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the History of Polish-Austrian Diplomacy in the 1970S

PRZEGLĄD ZACHODNI I, 2017 AGNIESZKA KISZTELIŃSKA-WĘGRZYŃSKA Łódź FROM THE HISTORY OF POLISH-AUSTRIAN DIPLOMACY IN THE 1970S. AUSTRIAN CHANCELLOR BRUNO KREISKY’S VISITS TO POLAND Polish-Austrian relations after World War II developed in an atmosphere of mutu- al interest and restrained political support. During the Cold War, the Polish People’s Republic and the Republic of Austria were on the opposite sides of the Iron Curtain; however, after 1945 both countries sought mutual recognition and trade cooperation. For more than 10 years following the establishment of diplomatic relations between Austria and Poland, there had been no meetings at the highest level.1 The first con- tact took place when the then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Bruno Kreisky, came on a visit to Warsaw on 1-3 March 1960.2 Later on, Kreisky visited Poland four times as Chancellor of Austria: in June 1973, in late January/early February 1975, in Sep- tember 1976, and in November 1979. While discussing the significance of those five visits, it is worth reflecting on the role of Austria in the diplomatic activity of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA). The views on the motives of the Austrian politician’s actions and on Austria’s foreign policy towards Poland come from the MFA archives from 1972-1980. The time period covered in this study matches the schedule of the Chancellor’s visits. The activity of the Polish diplomacy in the Communist period (1945-1989) has been addressed as a research topic in several publications on Polish history. How- ever, as Andrzej Paczkowski says in the sixth volume of Historia dyplomacji polskiej (A history of Polish diplomacy), research on this topic is still in its infancy.3 A wide range of source materials that need to be thoroughly reviewed offer a number of 1 Stosunki dyplomatyczne Polski, Informator, vol. -

Danish Cold War Historiography

SURVEY ARTICLE Danish Cold War Historiography ✣ Rasmus Mariager This article reviews the scholarly debate that has developed since the 1970s on Denmark and the Cold War. Over the past three decades, Danish Cold War historiography has reached a volume and standard that merits international attention. Until the 1970s, almost no archive-based research had been con- ducted on Denmark and the Cold War. Beginning in the late 1970s, however, historians and political scientists began to assess Danish Cold War history. By the time an encyclopedia on Denmark and the Cold War was published in 2011, it included some 400 entries written by 70 researchers, the majority of them established scholars.1 The expanding body of literature has shown that Danish Cold War pol- icy possessed characteristics that were generally applicable, particularly with regard to alliance policy. As a small frontline state that shared naval borders with East Germany and Poland, Denmark found itself in a difficult situation in relation to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) as well as the Soviet Union. With regard to NATO, Danish policymakers balanced policies of integration and screening. The Danish government had to assure the Soviet Union of Denmark’s and NATO’s peaceful intentions even as Denmark and NATO concurrently rearmed. The balancing act was not easily managed. A review of Danish Cold War historiography also has relevance for con- temporary developments within Danish politics and research. Over the past quarter century, Danish Cold War history has been remarkably politicized.2 The end of the Cold War has seen the successive publication of reports and white books on Danish Cold War history commissioned by the Dan- ish government. -

Die KPÖ in Der Konzentrationsregierung 1945–1947: Energieminister Karl Altmann WINFRIED R

12. Jg. / Nr. 3 ALFRED KLAHR GESELLSCHAFT September 2005 MITTEILUNGEN Preis: 1,1– Euro Die KPÖ in der Konzentrationsregierung 1945–1947: Energieminister Karl Altmann WINFRIED R. GARSCHA er im „Österreich-Lexikon“ war – und hier ist den Autoren der Par- Das, was über die Kenntnis einer bis- nach Karl Altmann sucht, fin- teigeschichte zuzustimmen – der Ab- lang unbekannten Facette der öster- Wdet einen dreieinhalbzeilige schluss einer Entwicklung, die bereits reichischen Nachkriegsgeschichte hinaus Eintrag mit den Geburts- und Sterbeda- mit der Ersetzung der kommunistischen am Wirken Altmanns als Energiemini- ten, dem Berufstitel (Obersenatsrat der durch ehemalige Nazi-Polizisten ab dem ster von Interesse ist, bezieht sich vor al- Gemeinde Wien) und der Mitteilung, Frühjahr 1947 in größerem Umfang be- lem auf die Bedingungen, unter denen er dass der KPÖ-Politiker 1945–47 Bun- gonnen hatte und ihren Höhepunkt mit kommunistische Politik betrieb: In einer desminister für Elektrifizierung und En- der Abberufung des kommunistischen absoluten Minderheitsposition als einzi- ergiewirtschaft gewesen sei.1 Leiters des staatspolizeilichen Büros der ger Minister seiner Partei in einer Regie- Auf den immerhin fast 600 Seiten der Bundespolizeidirektion Wien, Heinrich rung, deren übrige Mitglieder in ihm eine KPÖ-Geschichte2 wird Karl Altmann Dürmayer, im September 1947 erreicht Art Agenten der sowjetischen Besat- ganze zwei Mal kurz erwähnt. Einmal im hatte. Der internationale Bezug war der zungsmacht erblickten (was mit ihrem Zusammenhang mit seiner Entsendung 1947 voll ausbrechende Kalte Krieg, in eigenen Selbstverständnis als bedin- in die Bundesregierung als KPÖ-Mini- ganz Nord-, West- und Südeuropa wur- gungslose Parteigänger des „Westens“ ster, der der Partei eine „Kontrollmög- den kommunistische Minister aus den korrelierte), mit einem Beamtenapparat, lichkeit über die Regierungspolitik“ si- Regierungen gedrängt (übrigens viele der – von ganz wenigen, durch ihn selbst chern sollte (S. -

La Historia Del Balonmano En Chile

Universidad de Chile Instituto de la Comunicación e Imagen Escuela de Periodismo LA HISTORIA DEL BALONMANO EN CHILE MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL TITULO DE PERIODISTA INGA SILKE FEUCHTMANN PÉREZ PROFESOR GUÍA: EDUARDO SANTA CRUZ ACHURRA Santiago, Enero de 2014 Tabla de Contenidos FUNDAMENTACIÓN 1 I. PLANTEAMIENTO DEL PROBLEMA 7 1. Problema 7 2. Objetivo Principal 7 3. Objetivos Específicos 7 4. Propósito 8 CAPITULO I MARCO CONCEPTUAL 9 I. QUÉ ES EL DEPORTE 9 1. Etimología de la palabra deporte 9 2. Definición de deporte 11 3. Historia y desarrollo del deporte 15 4. Los deportes colectivos: el balonmano 21 II. EL BALONMANO 23 1. Uso del vocablo balonmano 23 2. La naturaleza del juego 24 3. Historia del balonmano en el mundo 29 4. Estructura internacional del balonmano 36 5. Organización Panamericana 39 ii III. TRATAMIENTO DEL DEPORTE EN CHILE 45 1. Cómo se comprende el deporte en Chile 45 2. Institucionalidad deportiva en Chile 50 IV. MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN DEPORTIVOS 54 1. Su relación con el balonmano 54 CAPITULO II PRIMERA ETAPA (1965-1973) 59 I. ORIGEN DEL BALONMANO EN CHILE 59 1. Los difusos y desconocidos comienzos del balonmano 59 2. La influencia alemana 61 3. De las colonias a la masificación 67 II. LOS PRIMEROS PASOS DE LA ORGANIZACIÓN NACIONAL 71 1. ¿Quién fue Pablo Botka, cuál era su plan? 71 2. El Estado y su apoyo al proyecto Botka 75 3. La experiencia escolar con el balonmano 80 III. MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN 84 1. El deporte que se conoce como hándbol 84 iii CAPITULO III SEGUNDA ETAPA (1975-1990) 87 I. -

Introduction

Introduction In recent years radical forms of anti-Zionism have once more revived with a vengeance in Europe and other parts of the world. Since the hate-fest at the UN- sponsored Durban Conference of September 2001 against racism, the claim that Israel is an “apartheid” state which practices “ethnic cleansing” against Palestinians has become particularly widespread. Such accusations are frequently heard today on European and North American campuses, in the media, the churches, among intellectuals and even among parts of the Western political elite. They have been given additional respectability in a polemical and tendentious book by former US President Jimmy Carter, one of the main architects of the Israeli- Egyptian Peace Agreement in 1979. Unfortunately Israel finds itself pilloried today as a state based on racism, colonialism, apartheid and even “genocide”. These accusations are now much more widespread than in the mid 1970s when the United Nations passed its notorious resolution equating Zionism with racism. At the same time, Palestinian hostility to Zionism, the escalation of terrorism and open antisemitism in the wider Arab- Muslim world has been greatly envenomed. However the seeds of this development were already present thirty years ago and indeed go back as far as the 1920s. What has changed is not so much the ideology but the fact that the culture of hatred among many Muslims has been greatly amplified by modern technologies and means of mass communication. Islamic fundamentalism and “holy war” have found an ever more fertile terrain in a backward, crisis-ridden Muslim world of Islamist jihad with anti-Americanism, hatred for Israel and continual media incitement steadily bringing the Middle East to the brink of the apocalypse. -

Fritz Hofmann • Hannes Androsch (Hg.) Leitlinien Leitl • Fritz Hofm T Exte Vonhanneloreexte E Hannes Androsch (Hg.) Inien Ann Bner •

Hannes Androsch (Hg.) • FRITZ HOFMANN • Hannes Androsch (Hg.) Androsch Hannes LEITLINIEN Rund drei Jahrzehnte lang zählte Fritz Hofmann zu den profiliertesten Kommunalpolitikern seiner Zeit. Vieles, was Wien • heute so lebens- und liebenswert macht, geht auf seine Initiative zurück. Donauinsel, U-Bahn, die Tangente, Fußgängerzonen, NN Wohnbau, Stadterneuerung – in den „Leitlinien für die A Stadtentwicklung“ vorgezeichnet – tragen seine Handschrift. M F 1928 als Wiener Arbeiterkind in Floridsdorf geboren, gehörte INIEN Fritz Hofmann jener Generation an, die Faschismus, Nazidiktatur, Kriegswirren, Befreiung, Wiederaufbau und wirtschaftlichen Aufstieg L hautnah miterlebte. Das vorliegende Buch hält den Lebensweg des „Zeitzeugen“ Hofmann fest und dokumentiert die Höhen und Tiefen seiner wechselvollen politischen Laufbahn. Die umfassende Darstel- FRITZ HO lung des Lebensweges von Fritz Hofmann bietet dem Leser zugleich • LEIT ein Stück kommunaler Stadthistorie bis hin zur Gegenwart. Texte von Hannelore Ebner 9 7 8 3 ISBN 978-3-9502631-1-4 950 263114 Wiens erster Planungsstadtrat – Kapitel 1 • FRITZ HOFMANN • LEITLINIEN Hannes Androsch (Hg.) Texte von Hannelore Ebner • 1 • Carl Gerold’s Sohn Verlagsbuchhandlung • FRITZ HOFMANN • LEITLINIEN Hannes Androsch (Hg.) Texte von Hannelore Ebner Impressum © 2008 by Carl Gerold’s Sohn Verlagsbuchhandlung KG, 1080 Wien Herausgeber: Hannes Androsch Autorin: Hannelore Ebner Coverfoto: Blick auf die Donauinsel (© Pressendienst der Stadt Wien) Bildnachweis: Alle Fotos © Pressedienst der Stadt Wien, Privatarchiv Fritz Hofmann, MA 13–media wien, Archiv Bezirksorganisation Floridsdorf außer: Wolfgang Simlinger (S. 98, 106, 116, 137, 157, 194, 268, 278); MA 29/Wurscher (S. 174), CompressPR (S. 258), Pressedienst der Stadt Wien/Kullmann (S. 226), Pressedienst der Stadt Wien/ Fürthner (S. 295), Ernst Schauer/Fernwärme Wien (S. 203), HBF/Pesata (S. -

Historisches 1 27

ÖSTERREICH JOURNAL NR. 2 / 6. 12. 2002 27 Historisches 1 27. 04. 1945 Provisorische Staatsregierung unter dem Vorsitz von Dr. Karl Renner. Ihr gehörten Vertreter der ÖVP, SPÖ und KPÖ zu gleichen Teilen an. 20. 12. 1945 Provisorische Bundesregierungegierung 1945 Kabinett Figl I (Sitzung vom 29. Dezember 1945) im Reichs- ratsaal im Parlament in Wien. v.l.n.r.: Ing. Vin- zenz Schumy, Johann Böhm, Eduard Heinl, Dr. Georg Zimmermann, Dr. Ernst Fischer, Johann Koplenig, Ing. Leopold Figl, Staats- kanzler Dr. Karl Renner, Dr. Adolf Schärf, Franz Honner, Dr. Josef Gerö, Josef Kraus, Andreas Korp, Ing. Julius Raab. Vorsitz: Karl Seitz. Bild: Institut für Zeitgeschichte © BKA/BPD 08. 11. 1949 Kabinett Figl II Bundeskanzler Leopold Figl (ÖVP), Vizekanzler Adolf Schärf (SPÖ), 5 Minister ÖVP, 4 Minister SPÖ, je 2 Staatssekretäre ÖVP und SPÖ 28. 10. 1952 Kabinett Figl III Bundeskanzler Leopold Figl (ÖVP), Vizekanzler Adolf Schärf (SPÖ), 5 Minister ÖVP, 4 Minister SPÖ, je 2 Staatssekretäre ÖVP und SPÖ 02. 04. 1953 Kabinett Raab I Gruppenfoto I. v.l.n.r. sitzend: BM f. ausw. Angelegenheiten Ing. Dr. Karl Gruber, BM f. Inneres Oskar Helmer, BK Ing. DDDR. Julius Raab, VK Dr. Adolf Schärf, BM f. Handel und Wiederaufbau DDDr. Udo Illig, v.l.n.r. stehend: SSekr. im BMaA Dr. Bruno Kreisky, BM f. sozi- ale Verwaltung Karl Maisel, SSekr. im BM f. Finanzen Dr. Fritz Bock, SSekr. im BM f. Inne- res Ferdinand Graf, BM f. Finanzen DDr. Rein- hard Kamitz, BM f. Unterricht Dr.Ernst Kolb, SSekr. im BM f. Handel und Wiederaufbau Dipl. Ing. Raimund Gehart, BM f. -

Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Fuchs, Andreas; Richert, Katharina Working Paper Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving? Discussion Paper Series, No. 604 Provided in Cooperation with: Alfred Weber Institute, Department of Economics, University of Heidelberg Suggested Citation: Fuchs, Andreas; Richert, Katharina (2015) : Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving?, Discussion Paper Series, No. 604, University of Heidelberg, Department of Economics, Heidelberg, http://dx.doi.org/10.11588/heidok.00019769 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127421 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von -

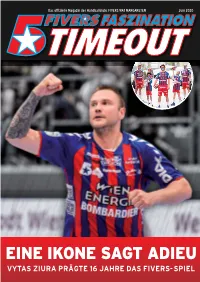

Timeout Ausgabe Juni 2020

Das offizielle Magazin des Handballclubs Fivers WAT MArgAreTen Juni 2020 eine ikone sagt adieu Vytas Ziura prägte 16 Jahre das fiVers-spiel // XXXXXXXXXXXX DIE WIEN ENERGIE- VORTEILSWELT. Die Gratis-App voller Vorteile für unsere Kundinnen und Kunden. Jetzt downloaden Sport-Veranstaltungen, Führungen, Kino und Konzerte – die gratis Vorteilswelt steckt für alle Wien Energie-Kundinnen und -Kunden voller Angebote, Gewinnspiele und Ermäßigungen. Jetzt im App Store oder bei Google Play downloaden. Mehr Informationen auf wienenergie.at/vorteilswelt Vorteilswelt >>> 2 www.wienenergie.at Wien Energie, ein Partner der EnergieAllianz Austria. 021462T3 WE Vorteilswelt V 210x297 TimeoutMagazin ETMärzApril2019 iWC.indd 1 12.03.19 15:07 Inhalt // // editOrial CORONA SPUCKTE IN DIE SUPPE 4 Die Unvollendete der FIVERS. EINE KARRIERE IN BILDERN DIE WIEN ENERGIE- 10 Das war Vytas Ziura in Margareten. OFFENE WORTE ZUM ABSCHIED 12 Das persönliche Ziura-Interview. VORTEILSWELT. MASKENBALL IN MARGARETEN >>> LIEBE FIVERS-FANS! 26 Gewista-CEO Solta im Gespräch. Wir sind FIVERS – unser Leitspruch steht für Zusammenhalt, Kampfgeist Die Gratis-App voller Vorteile für und Leidenschaft. Attribute, die gerade in diesen herausfordernden Zeiten besonders gefragt sind. DER EWIGE FIVERS-faN 30 Nach einer starken Saison wurden unsere Titelträume von einem Tag auf unsere Kundinnen und Kunden. Erwin Lanc feierte den 90er. den anderen beendet. Traurig, aber damit konnten wir uns nicht lange aufhalten. Denn es ging - und geht noch lange - um die Existenz des besten FOLGE DEN FIVERS AUF FACEBOOK! Handballclubs des Landes. www.facebook.com/fivershandballteam Zusammenhalt, Kampfgeist und Leidenschaft waren gefragt. Alle, wirklich alle FIVERS vom Vorstand bis zum Kuratorium, den Sponsoren, den Spielern, Trainern und Betreuern haben eindrucksvoll bewiesen: Wir sind FIVERS! So können wir heute vorsichtig sagen, dass wir zumindest wirtschaftlich Licht IMPRESSUM am Ende des Pandemie-Tunnels sehen. -

AA Auswärtiges Amt ADN Allgemeiner Deutscher Nachrichtendienst Adr Archiv Der Republik Akvvi Archiv Des Karl Von Vogelsang-Instituts Anm

Anhang Abkürzungen AA Auswärtiges Amt ADN Allgemeiner Deutscher Nachrichtendienst AdR Archiv der Republik AKvVI Archiv des Karl von Vogelsang-Instituts Anm. Anmerkung AP Associated Press APA Austria Presse Agentur Bd. Band BKA Bundeskanzleramt BKA/AA Abteilung für Auswärtige Angelegenheiten im Bundeskanzleramt BMEIA Bundesministerium für Europäische und Internationale Angelegen- heiten BMfAA Bundesministerium für Auswärtige Angelegenheiten BMfHGI Bundesministerium für Handel, Gewerbe und Industrie BStU Bundesbeauftragte für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik ČSSR Československá socialistická republika DDR Deutsche Demokratische Republik DLF Deutschlandfunk EA Europa-Archiv ECE Economic Commission for Europe EFTA European Free Trade Association EG Europäische Gemeinschaft EGKS Europäische Gemeinschaft für Kohle und Stahl ER Europarat ESK Europäische Sicherheitskonferenz EVG Europäische Verteidigungsgemeinschaft EWG Europäische Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft FAZ Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung FRUS Foreign Relations of the United States GZl. Geschäftszahl IAEO Internationale Atomenergie-Organisation INF Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces KP Kommunistische Partei KPdSU Kommunistische Partei der Sowjetunion KPÖ Kommunistische Partei Österreichs KSZE Konferenz über Sicherheit und Zusammenarbeit in Europa KVAE Konferenz über Vertrauens- und Sicherheitsbildende Maßnahmen und Abrüstung in Europa 448 Anhang MBFR Mutual and Balanced Force Reductions MRP Ministerratsprotokolle MV Multilaterale Vorbesprechungen -

EHF Annual Report 2011 10.6 MB

2011 CONTENTS 2011 Introduction from the President 4 National Teams 7 EHF Men’s EURO 2012 Serbia 8 EHF Women’s EURO 2012 Netherlands 10 CONTENTS 2011 European Beach Handball Championships 12 2011 YAC European Beach Handball Championships 14 2011 EHF Women’s 17 & 19 European Championships 16 2011 Men’s European Open / 2011 European Masters 17 2011 IHF / EHF Men’s Challenge Trophy / 11th EYOF 18 IHF Competitions 19 Club Teams 21 2010/11 VELUX EHF Champions League 22 VELUX EHF FINAL4 24 2010/11 EHF Women’s Champions League 26 European Cups 28 2010/11 EHF Cup 29 2010/11 Challenge Cup 30 2010/11 Cup Winners’ Cup 31 2009 EBT & EBT Masters 32 2011 Draw Highlights 33 Round Table 35 20th Anniversary of the European Handball Federation 36 11th EHF Extraordinary Congress 39 10th EHF Conference of Presidents 40 6th Conference for Secretaries General 41 Meetings 42 Workshops 44 Partners 45 Forming the Future 47 EHF Competence Academy & Network 48 Methods & Developments 49 Courses & Seminars 50 Coaching 51 Referees 52 Transfers 55 This is the EHF 57 EHF Corporate Network 58 EHF Corporate & Office Structure 60 EHF Executive & Commissions 62 Information & Communications 68 EHF Publications 69 EHF Websites 70 EHF Office 71 EHF Marketing GmbH 72 EHF Calendar 2012 76 EHF Secretary General’s Message 78 EHF ANNUAL REVIEW 2011 3 FROM The PRESIDENT Ladies and Gentlemen, dear friends in sport! Welcome to the 2011 EHF Annual Review. With this colourful document, we invite you to take a look back at the past year in European handball and as the business end draws to a close I can easily say that 2011 has been most eventful for the European Handball Federation. -

Historical Dictionary of International Intelligence Second Edition

The historical dictionaries present essential information on a broad range of subjects, including American and world history, art, business, cities, countries, cultures, customs, film, global conflicts, international relations, literature, music, philosophy, religion, sports, and theater. Written by experts, all contain highly informative introductory essays on the topic and detailed chronologies that, in some cases, cover vast historical time periods but still manage to heavily feature more recent events. Brief A–Z entries describe the main people, events, politics, social issues, institutions, and policies that make the topic unique, and entries are cross- referenced for ease of browsing. Extensive bibliographies are divided into several general subject areas, providing excellent access points for students, researchers, and anyone wanting to know more. Additionally, maps, pho- tographs, and appendixes of supplemental information aid high school and college students doing term papers or introductory research projects. In short, the historical dictionaries are the perfect starting point for anyone looking to research in these fields. HISTORICAL DICTIONARIES OF INTELLIGENCE AND COUNTERINTELLIGENCE Jon Woronoff, Series Editor Israeli Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana, 2006. Russian and Soviet Intelligence, by Robert W. Pringle, 2006. Cold War Counterintelligence, by Nigel West, 2007. World War II Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2008. Sexspionage, by Nigel West, 2009. Air Intelligence, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2009. Middle Eastern Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana and Muhammad Suwaed, 2009. German Intelligence, by Jefferson Adams, 2009. Ian Fleming’s World of Intelligence: Fact and Fiction, by Nigel West, 2009. Naval Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2010. Atomic Espionage, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2011. Chinese Intelligence, by I. C.