The Holman Humbug Bond G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rio Grande Station Cape May County, NJ Name of Property County and State 5

NPS Form 10-900 JOYf* 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) !EO 7 RECE!\ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service n m National Register of Historic Places Registration Form ii:-:r " HONAL PARK" -TIO.N OFFICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategones from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form I0-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property________________________________________________ historic name R'Q Grande Station____________________________________ other names/site number Historic Cold Spring Village Station______________________ 2. Location street & number 720 Route 9 D not for publication city or town Lower Township D vicinity state New Jersey_______ code NJ county Cape May_______ code 009 zip code J5§204 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Q nomination G request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property S meets D doss not meet the National Register criteria. -

Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) New Jersey

Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) for New Jersey By ORF 467 Transportation Systems Analysis, Fall 2004/05 Princeton University Prof. Alain L. Kornhauser Nkonye Okoh Mathe Y. Mosny Shawn Woodruff Rachel M. Blair Jeffery R Jones James H. Cong Jessica Blankshain Mike Daylamani Diana M. Zakem Darius A Craton Michael R Eber Matthew M Lauria Bradford Lyman M Martin-Easton Robert M Bauer Neset I Pirkul Megan L. Bernard Eugene Gokhvat Nike Lawrence Charles Wiggins Table of Contents: Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction to Personal Rapid Transit .......................................................................................... 3 New Jersey Coastline Summary .................................................................................................... 5 Burlington County (M. Mosney '06) ..............................................................................................6 Monmouth County (M. Bernard '06 & N. Pirkul '05) .....................................................................9 Hunterdon County (S. Woodruff GS .......................................................................................... 24 Mercer County (M. Martin-Easton '05) ........................................................................................31 Union County (B. Chu '05) ...........................................................................................................37 Cape May County (M. Eber '06) …...............................................................................................42 -

November 14, 2014 in Honor of Veterans Day This Week, My Thanks

Dear All: November 14, 2014 In honor of Veterans Day this week, my thanks go out to the men and women of yesterday, today and tomorrow who have and who will sacrifice so much for the U.S.A. It seems to me, the train world really comes alive during the holidays to help us remember years gone by. So many of you volunteer your time to set up and run a layout at various locations, how amazing it is because you are touching the lives of so many in a positive and healthy way. Bravo! I would love to include YOUR story with the next e‐ blast that connects your family memories with the holiday season and the world of trains. I think it would be great to share these stories over the next several weeks leading up to the end of 2014! What did you say? You have pictures to go along with the story, well send them along to me and as long as they are family friendly I’ll share them with those that read the eblast. As a reminder, the eblasts and attachments will be placed on the WB&A website under the “About” tab for your viewing/sharing pleasure http://www.wbachapter.org/2014%20E‐ Blast%20Page.htm The attachments are contained in the one PDF attached to this email in an effort to streamline the sending of this email and to ensure the attachments are able to be received. If you need a PDF viewer to read the document which can be downloaded free at http://www.adobe.com/products/acrviewer/acrvd nld.html. -

Transportation Trips, Excursions, Special Journeys, Outings, Tours, and Milestones In, To, from Or Through New Jersey

TRANSPORTATION TRIPS, EXCURSIONS, SPECIAL JOURNEYS, OUTINGS, TOURS, AND MILESTONES IN, TO, FROM OR THROUGH NEW JERSEY Bill McKelvey, Editor, Updated to Mon., Mar. 8, 2021 INTRODUCTION This is a reference work which we hope will be useful to historians and researchers. For those researchers wanting to do a deeper dive into the history of a particular event or series of events, copious resources are given for most of the fantrips, excursions, special moves, etc. in this compilation. You may find it much easier to search for the RR, event, city, etc. you are interested in than to read the entire document. We also think it will provide interesting, educational, and sometimes entertaining reading. Perhaps it will give ideas to future fantrip or excursion leaders for trips which may still be possible. In any such work like this there is always the question of what to include or exclude or where to draw the line. Our first thought was to limit this work to railfan excursions, but that soon got broadened to include rail specials for the general public and officials, special moves, trolley trips, bus outings, waterway and canal journeys, etc. The focus has been on such trips which operated within NJ; from NJ; into NJ from other states; or, passed through NJ. We have excluded regularly scheduled tourist type rides, automobile journeys, air trips, amusement park rides, etc. NOTE: Since many of the following items were taken from promotional literature we can not guarantee that each and every trip was actually operated. Early on the railways explored and promoted special journeys for the public as a way to improve their bottom line. -

FRA Guide for Preparing Accident/Incident Reports

FRA Guide for Preparing Accident/Incident Reports U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration Office of Railroad Safety DOT/FRA/RRS-22 Published: May 23, 2011 Effective: July 1, 2011 This page intentionally left blank MAIL MONTHLY ACCIDENT/INCIDENT REPORTING SUBMISSIONS TO: FRA Project Office 2600 Park Tower Drive, Suite 1000 Vienna, VA 22180 Please refer to http://safetydata.fra.dot.gov/OfficeofSafety, and click on “Click Here for Changes in Accident/Incident Recordkeeping and Reporting” for updated information. Preface The Federal Railroad Administration’s (FRA) regulations on reporting railroad accidents/incidents are found primarily in Title 49 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 225.1 The purpose of the regulations in Part 225 is to provide FRA with accurate information concerning the hazards and risks that exist on the Nation’s railroads. See § 225.1. FRA needs this information to effectively carry out its regulatory and enforcement responsibilities under the Federal railroad safety statutes.2 FRA also uses this information for determining comparative trends of railroad safety and to develop hazard elimination and risk reduction programs that focus on preventing railroad injuries and accidents. 1 For brevity, further references in the Guide to sections in 49 CFR Part 225 will omit “49 CFR” and include only the section, e.g., § 225.9. 2 Title 49 U.S.C. chapters 51, 201–213. iv Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 1. Overview of Railroad Accident/Incident Recordkeeping and Reporting Requirements and Miscellaneous Provisions and Information ............................................................................... 4 1.1 General ............................................................................................................................. 4 1.1.1 Purpose of the FRA Guide for Preparing Accident/Incident Reports ....................... -

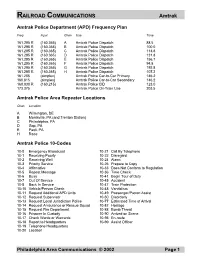

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak Amtrak Police Department (APD) Frequency Plan Freq Input Chan Use Tone 161.295 R (160.365) A Amtrak Police Dispatch 88.5 161.295 R (160.365) B Amtrak Police Dispatch 100.0 161.295 R (160.365) C Amtrak Police Dispatch 114.8 161.295 R (160.365) D Amtrak Police Dispatch 131.8 161.295 R (160.365) E Amtrak Police Dispatch 156.7 161.295 R (160.365) F Amtrak Police Dispatch 94.8 161.295 R (160.365) G Amtrak Police Dispatch 192.8 161.295 R (160.365) H Amtrak Police Dispatch 107.2 161.205 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Primary 146.2 160.815 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Secondary 146.2 160.830 R (160.215) Amtrak Police CID 123.0 173.375 Amtrak Police On-Train Use 203.5 Amtrak Police Area Repeater Locations Chan Location A Wilmington, DE B Morrisville, PA (and Trenton Station) C Philadelphia, PA D Gap, PA E Paoli, PA H Race Amtrak Police 10-Codes 10-0 Emergency Broadcast 10-21 Call By Telephone 10-1 Receiving Poorly 10-22 Disregard 10-2 Receiving Well 10-24 Alarm 10-3 Priority Service 10-26 Prepare to Copy 10-4 Affirmative 10-33 Does Not Conform to Regulation 10-5 Repeat Message 10-36 Time Check 10-6 Busy 10-41 Begin Tour of Duty 10-7 Out Of Service 10-45 Accident 10-8 Back In Service 10-47 Train Protection 10-10 Vehicle/Person Check 10-48 Vandalism 10-11 Request Additional APD Units 10-49 Passenger/Patron Assist 10-12 Request Supervisor 10-50 Disorderly 10-13 Request Local Jurisdiction Police 10-77 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-14 Request Ambulance or Rescue Squad 10-82 Hostage 10-15 Request Fire Department -

The Cape May Branch an Important New Jersey Transportation Asset

The Cape May Branch an important New Jersey transportation asset Transportation, Mobility & Economic Engine Presented by: Paul Mulligan New Jersey Association of Railroad Passengers (NJ-ARP) 1 The Cape May Branch • The Cape May Branch, owned by New Jersey Transit (NJT), is an important New Jersey rail transportation resource that should be optimized to serve the special tourist-based economy of Cape May City and both Cape May and Atlantic counties. • A capital commitment to the Cape May Branch ROW (right of way), including the Cape May Canal bridge (an asset owned by the State of NJ), is key to facilitating transportation service in this very special part of New Jersey. 2 Vision Statement The Cape May Branch can help satisfy the transportation and mobility needs of Cape May County by providing PASSENGER AND FREIGHT RAIL SERVICE for: – Park & Ride service for day visitors to Cape May City shopping, entertainment & tours who are staying at other regional resort towns & campgrounds – Freight Transportation for light industrial development in Woodbine enhancing employment and ratable base for Woodbine & Cape May County – Promoting the re-creation of regional history – Strategic Transport for the delivery of supplies & building material as needed for disaster recovery – Aid in the evacuation of seniors and those lacking transportation resources 3 Tourism Tourism is the engine that drives the economy of Atlantic & Cape May Counties as reported by the Atlantic City Press, March 30, 2007. • Mobility of our visitors when they are in our Key to success in tourism industry: More ooohs, ahhhs and ohhhs region is a big image problem -- Garden State By MAYA RAO Staff Writer, (609) 272 Parkway gridlock & lack of island parking. -

Merry Christmas from the Lancaster Chapter, Inc., N.R.H.S

Volume 51 Number 12 District 2 - Chapter Website: www.nrhs1.org December 2020 MERRY CHRISTMAS FROM THE LANCASTER CHAPTER, INC., N.R.H.S. Lancaster Dispatcher Page 2 December 2020 THE POWER DIRECTOR “NEWS FROM THE RAILROAD WIRES” AMTRAK CEO TELLS HEARING COMPANY moving forward with these long-needed projects absent a level of funding PROJECTS 72% DECLINE IN RIDERSHIP to support those capital investments,” he said. WASHINGTON, Oct. 21, 2020. By Dan Zukowski Lack of funding for capital projects could cause a further 700 layoffs, with Trains News Wire — Amtrak is projecting fiscal 1,600 more due to lose their jobs without additional funding to maintain 2021 ridership of just 9 million, a 72% decline state services. Amtrak is currently furloughing 2,000 union workers and 100 from 2019’s record 32.5 million passengers, CEO managers, bringing the potential total to 4,400. William Flynn told members of the Senate Commerce Committee, who Dennis Pierce, testifying for the Teamsters Rail Conference, said that expressed skepticism and concern over the move to three-day-a-week Amtrak expects to furlough nearly a quarter of its passenger engineers, service for most long-distance trains. including all student engineers. In testimony submitted Wednesday morning, Flynn qualifies his estimate by saying that “these assumptions rely on an effective and AMTRAK INTRODUCES ‘NEXT DAY TRAVEL’ BOOKING FEATURE widely-distributed vaccine becoming available by the middle of next Updated downloadable schedules for long-distance trains also part of calendar year — which we know is not a guaranteed outcome.” changes to reflect triweekly service At that low passenger level, revenues would come in at just $598 million, WASHINGTON, Oct. -

ITS Stakeholders ITS Stakeholders Description

ITS Stakeholders ITS Stakeholders Description AMTRAK Nationwide Passenger Rail Organization with service to entire north east corridor. Burlington County Bridge Commission Operates and maintains 8 bridges in Burlington County, NJ, including two toll bridges. Cape May Seashore Lines Provides train service between Tuckahoe and Cape May. CVO Inspector Generic commercial vehicle inspection providers. DelDOT - Delaware Department of Transportation Delaware Department of Transportation DRBA - Delaware River and Bay Authority Delaware River and Bay Authority (DRBA), a New Jersey-Delaware bi-state agency, operates the Delaware Memorial Twin Bridges, the Cape May-Lewes Ferry system, the Three Forts Ferry Crossing, and the New Castle, Cape May, Millville, Delaware Airpark and Dover Civil Air Terminal Airports. DRJTBC - Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Operates 20 river crossings over 139 miles of river within its jurisdiction, Commission stretching from northern Burlington County, New Jersey and Bucks County, Pennsylvania northward to the New York State Line, Includes 7 toll bridges. DRPA - Delaware River Port Authority The Delaware River Port Authority of Pennsylvania and New Jersey (DRPA) is a regional transportation and economic development agency serving the people of Southeastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey. Operates 4 toll bridges in the region and the PATCO Speedline. DRPA also owns the RiverLink Ferry, the Philadelphia Cruise Terminal @ Pier 1 and the AmeriPort Intermodal Rail Center. DRPA PATCO - Port Authority Transit Corporation Port Authority Transit Corporation (PATCO). Operates the commuter rail (Speedline) transit between Philadelphia and New Jersey. A subsidiary of the Delaware River Port Authority. DVRPC - Delaware Valley Regional Planning Serving the Greater Philadelphia-Camden-Trenton area for almost 40 years, Commission DVRPC works to foster regional cooperation in a nine-county, two-state area. -

Edward H. Weber Collection of Railroad Timetables 2573

Edward H. Weber collection of railroad timetables 2573 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Manuscripts and Archives PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Edward H. Weber collection of railroad timetables 2573 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................. 11 Biographical Note ........................................................................................................................................ 11 Scope and Content ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................... 13 Related Materials ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Controlled Access Headings ........................................................................................................................ 15 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................... 15 Public timetables - Amtrak ...................................................................................................................... -

Southern New Jersey Freight and Logistics Industry Context and Eco- Nomic Growth Visioning Plan

Southern New Jersey Freight and Logistics Industry Context and Eco- nomic Growth Visioning Plan New Jersey Department of Transportation September 2008 Table of Contents Executive Summary i I. Introduction 1 II. The Southern New Jersey Regional Context 3 III. Strengths and Characteristics Requiring Improvement 16 IV. Visioning Plan 21 Executive Summary This report presents a visioning plan for advancing the freight and logistics indus- try in New Jersey, with particular emphasis on the southern portion of the State. The freight and logistics industry is defined as any activity needed for cargo movement and includes warehousing/distribution centers, maritime/port activities, trucking, rail freight, air cargo, and support services. New Jersey’s freight and logistics industry is enormous, employing more than 500,000 workers to move a wide spectrum of domestic and international products. By creating a stronger freight and logistics industry in southern New Jersey, the State can enhance its overall economic competitiveness, as well as generate enhanced opportunities for the State’s residents and businesses. The visioning plan integrates: An understanding of the context – existing conditions in the Southern New Jersey region, including the population, economy, unique industries and transportation infrastructure. An assessment of the strengths and weaknesses, with a particular focus on the freight industry. A series of dialogues with key executives and industry groups that ob- tained informed opinions, sharpened the understanding of the area, and identified a common set of potential strategies for moving forward. Unique Strengths The strengths of the Southern New Jersey Region include: “The Supply Chain Corridor” – a considerable amount of acreage de- voted to distribution and manufacturing operations along the New Jersey Turnpike and Interstate 295 Corridor. -

New Jersey Railroad Law Enforcement Guide

NEW JERSEY RAILROAD LAW ENFORCEMENT GUIDE R R FOR RESPONSE TO RAILROAD INCIDENTS Dedicated to all law enforcement who served, are serving and will serve in the future. 1 JURISDICTION AND AUTHORITY Under 49 US Code § 28101 Federal Government defines the jurisdiction of railroad police officers and allows each state to control jurisdictional authority. In the State of New Jersey (N.J.S.A. 48:3-38) railroad police officers carry the title of “Special Agent”. Railroad Special Agents are commissioned by the State of New Jersey through the Governor’s Office and enjoy the privileges of full law enforcement authority. DISCLAIMER This Law Enforcement Guide is intended to assist New Jersey Law Enforcement personnel when investigating railroad-related crimes, answering calls for service or conducting motor vehicle investigations on railroad property. While the statutes listed here are intended as reference material, this compendium does not include all applicable law. Additional statutes and local ordinances may be relevant in an enforcement action. Consult your Agency legal advisor or local prosecutor. Do not change any departmental policy or procedure based on this reference material without the review and approval of your legal advisor. This document is for reference only and does not constitute legal advice. The author and contributing entities make no claim as to the accuracy, completeness or adequacy of this guide and expressly disclaim liability for errors or omission in the content. Copyright © 2018 by New Jersey Operation Lifesaver. All rights reserved. 2 Police work is inherently dangerous on any given day, the addition of working on or along any railroad makes that danger greater.