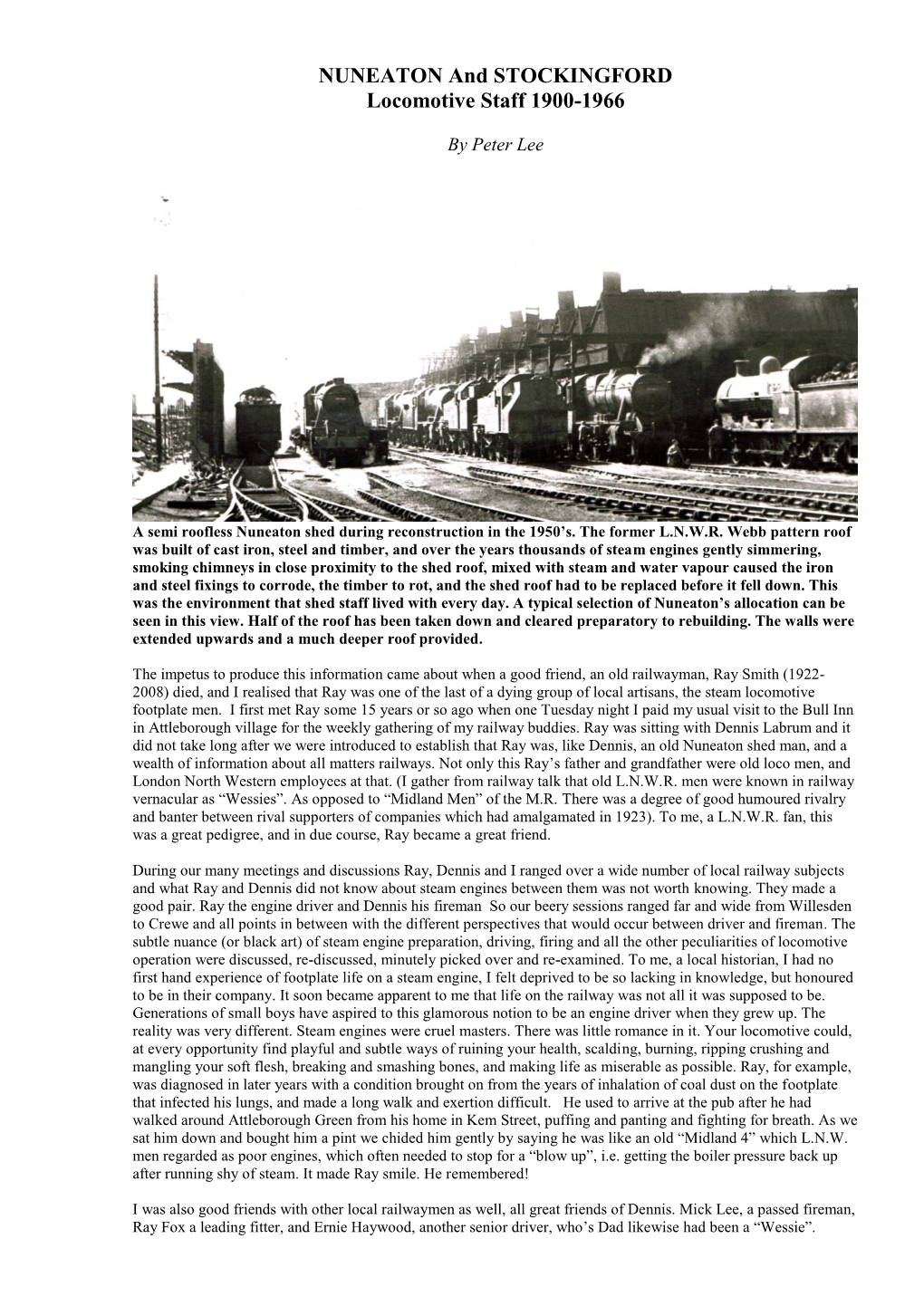

Nuneaton & Stockingford Locomotive Staff 1900-1966

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tourism Leaflet 2021

Visit Cannock Chase Your guide on getting more from your visit to Our Visitor Centres Birches Valley Visitor Centre Marquis Drive Visitor Centre Museum of Cannock Chase Cannock Chase National Trust Shugborough Estate The Cannock Chase District is nestled in the heart of the West Midlands, Chasewater Country Park in the county of Staffordshire. We are a historical, proud District spanning The Wolseley Centre - Staffordshire Wildlife Trust HQ across three town centres, Cannock, Hednesford and Rugeley. Some of our visitor centres sit just outside the district. For full details, take a look at page 13 Visit us to enjoy incredible shopping at McArthuGlen’s Designer Outlet West Midlands, only a 20 minute walk from Cannock town centre and only 10 minutes walk from Cannock Train Station. And why not explore, walk and mountain bike in the Cannock Chase Area Well Worth a Visit of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Less than 20 minutes drive from our three town centres. McArthurGlen Designer Outlet West Midlands Cannock Chase AONB Go Ape Hednesford Hills Raceway Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery Planet Ice Skating Rink Cannock Cinema Prince of Wales Theatre The Rugeley Rose Theatre Cannock Chase Leisure Centre and Golf Course Rugeley Leisure Centre Within the County Drayton Manor Theme Park SnowDome Alton Towers Resort Trentham Estate - Shopping, Monkey Forest and Gardens National Memorial Arboretum Photographs courtesy of Michelle Williams, 2 Margaret Beardsmore and Carole & David Perry 3 A well connected place... Heritage Trail Map By road By bus and coach A great walking and cycling route linking Rugeley, Hednesford & Cannock Cannock Chase The A5 and A34 AONB Bus links to all local and surrounding areas trunk roads, M6 and as well as wider areas including Central M6 toll provide Birmingham and Walsall. -

Infrastructure Delivery Plan Contents 1 Introduction 3

APPENDIX O Infrastructure Delivery Plan 1 March 2018 Infrastructure Delivery Plan Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Policy Context 5 3 Funding & Delivery 8 4 Strategic Infrastructure 11 5 Local Infrastructure Needs 58 Appendices A Lichfield District Integrated Transport Strategy 93 B River Mease SAC Water Catchment Area 94 C Cannock Chase SAC Zone of Influence 96 March 2018 Infrastructure Delivery Plan 3 1 Introduction 1.1 Infrastructure Planning is an essential element in ensuring that the Local Plan Strategy and Local Plan Allocation Document is robust and deliverable. 1.2 The term infrastructure is broadly used for planning purposes to define all of the requirements that are needed to make places function efficiently and effectively and in a way that creates sustainable communities. Infrastructure is commonly split into three main categories, defined as: Introduction Physical: the broad collection of systems and facilities that house and transport people and goods, and provide services e.g. transportation networks, housing, energy supplies, 1 water, drainage and waste provision, ICT networks, public realm and historic legacy. Green: the physical environment within and between our cities, towns and villages. A network of multi-functional open spaces, including formal parks, gardens, woodland, green corridors, waterways, street trees and open countryside. Social & Community: the range of activities, organisations and facilities supporting the formation, development and maintenance of social relationships in a community. It can include the provision -

WMRU June 2014 Cover

West Midlands Rail User Issue 8 JUNE 2014 £2 www.campaignforrail.org.uk ON OTHER PAGES: 10. Rail continues to grow ON OTHER PASGES: 2. Comment 11. Metro developments 3.BirminghamCurzon 12.Whypaymore? 4. Cross City South grows 13. Bushbury Junction 6. CfR’s Annual Meeting 14. Snippets 7. TripleTriumphforStourbridgeGroup 15. Thenextstationis…..Stone 8. TheFutureisWestMidlandsRail 16. TrackliftedtoCauldonLowe The voice of Campaign for Rail in the West Midlands COMMENT Imagine buying a vacuum cleaner and taking it back next day because it didn’t work. ‘Were you trying to use late afternoon? It’s not valid at that time. We didn’t tell you when we sold you it.’ Instead of vacuum cleaner, read ‘off peak rail ticket’. Twice recently I have bought rail tickets from booking clerks who have only asked if I am travelling after 09.30. In both cases, I later discovered they were not valid for my afternoon return journey. The problem is with Cross Country. It has decided some afternoon trains are ‘peak’ but it doesn’t identify them in its timetables and Cross Country unhelpfully only tells us, ‘off peak times vary by route’. As the i newspaper said about rail tickets re- cently, ‘Peak time is now more difficult to define in a sentence than the Higgs boson.’ Equally useless from Cross Country is, ‘Break of journey is generally permitted unless prohibited for the journey you are making.’ Each ticket says, ‘Route: Any permitted’ and ‘Validity: See restrictions.’ But where? A CfR member tried to buy a ticket to Kidderminster which involved going south via Bromsgrove to Droitwich Spa and then doubling back. -

Signal and Track Improvements for Trent Valley Line Passengers

Signal and track improvements for Trent Valley Line passengers July 19, 2021 Rail passengers travelling between Stafford and Rugby are being urged to ‘look before they book’ ahead of a month of weekend railway upgrades. The major improvements to the Trent Valley Line will see new railway track laid and signalling – the traffic lights of the railway – improved. Once complete, it will mean smoother, more reliable journeys for passengers who use this busy stretch of the West Coast main line. Passengers are being urged to check www.nationalrail.co.uk to plan their journeys while the essential work is carried out on 24-25 July, 31 July-1 August, 7-8 August and 14-15 August. To keep London Northwestern Railway and West Midlands Railway passengers on the move, buses will replace trains between: Rugby – Stafford Hednesford – Rugeley Trent Valley Bermuda Park/Coventry Arena – Nuneaton A revised timetable will be in place to minimise disruption for passengers. Avanti West Coast passengers will also see fewer trains and slightly longer journey times with services diverted via Birmingham New Street. James Dean, Network Rail’s West Coast South route director, said: “We’re really pleased to be investing in the Trent Valley Line so that passengers get the journeys they deserve as they continue to return to the railway. The investment is a key part of our work to support the post-pandemic recovery, helping the country build back better. “Services will only be affected during the weekends with some journeys replaced by buses to ensure passengers can still get to where they need to be. -

National Rail Route Diagram

Thurso Georgemas Junction Wick Great Britain Far North Helmsdale Line Lairg Tain Invergordon Garve Dingwall Nairn Forres Elgin ISLE OF SKYE Achnasheen Inverness Keith Strathcarron national rail Huntly Plockton Stromeferry Kyle of Lochalsh Aviemore Inverurie route diagram Dyce Kingussie HIGHLAND December 2020 Spean Aberdeen Glenfinnan Bridge Mallaig Blair Atholl Fort William Stonehaven High speed route HS2 under construction / planned Rannoch Montrose West Pitlochry Principal routes Highland Regional routes Lines Arbroath Local routes Tyndrum Oban Limited service Dalmally Crianlarich Dundee Elizabeth Line and East West Rail under construction Perth Gleneagles Cupar Arrochar & Tarbet Dunblane Major cities with multiple stations Fife Markinch Stirling Circle Alloa Kirkcaldy All lines shown except in London area Garelochhead Dunfermline Inverkeithing Larbert Falkirk within grey line Balloch Grahamston Edinburgh Edinburgh Helensburgh Upper Gateway Waverley Helensburgh Central North Berwick Milngavie Lenzie Airport interchange Falkirk Linlithgow Haymarket Dunbar Dumbarton Central Maryhill High Railair coach link with Heathrow Airport Cumbernauld Westerton Springburn Bathgate Berwick-upon-Tweed Ferry interchange Queen Street Drumgelloch Partick Airdrie Coatbridge Port Paisley Galashiels Not all stations shown Glasgow Gilmour St Central Kirknewton Gourock Inverclyde Whifflet Shotts Tweedbank Chathill Wemyss Bay Line Paisley Newton Holytown Ayr Canal Cathcart EAST COAST Largs Line Stewarton Motherwell Carluke Ardrossan Kilwinning Neilston Alnmouth -

West Midlands and Chilterns Route Utilisation Strategy Draft for Consultation Contents 3 Foreword 4 Executive Summary 9 1

November 2010 West Midlands and Chilterns Route Utilisation Strategy Draft for Consultation Contents 3 Foreword 4 Executive summary 9 1. Background 11 2. Dimensions 20 3. Current capacity, demand, and delivery 59 4. Planned changes to infrastructure and services 72 5. Planning context and future demand 90 6. Gaps and options 149 7. Emerging strategy and longer-term vision 156 8. Stakeholder consultation 157 Appendix A 172 Appendix B 178 Glossary Foreword Regional economies rely on investment in transport infrastructure to sustain economic growth. With the nation’s finances severely constrained, between Birmingham and London Marylebone, as any future investment in transport infrastructure well as new journey opportunities between Oxford will have to demonstrate that it can deliver real and London. benefits for the economy, people’s quality of life, This RUS predicts that overall passenger demand in and the environment. the region will increase by 32 per cent over the next 10 This draft Route Utilisation Strategy (RUS) sets years. While Network Rail’s Delivery Plan for Control out the priorities for rail investment in the West Period 4 will accommodate much of this demand up Midlands area and the Chiltern route between to 2019, this RUS does identify gaps and recommends Birmingham and London Marylebone for the next measures to address these. 30 years. We believe that the options recommended Where the RUS has identified requirements for can meet the increased demand forecast by this interventions to be made, it seeks to do so by making RUS for both passenger and freight markets and the most efficient use of capacity. -

Q1 What Are the Main Arguments for Or Against HSR?

Written evidence from The Chiltern Society (HSR81) Q1 What are the main arguments for or against HSR? 1.1 To answer this question meaningfully it is essential to distinguish between the concept of High Speed Rail (HSR), the proposed HS2 project and the issue of whether the latter is an effective response to the Government’s case for the former. 1.2 HSR covers a wide spectrum of different rail track and train design speeds1. If there is a demonstrable case for HSR, one key question is ‘what design speed concept(s) will provide the best strategic fit and value for money for England, Wales and Scotland?’ 1.3 The Chiltern Society is not opposed to the concept of HSR. It is though strongly opposed to the currently proposed HS2 project, which has been evolved through a highly flawed, and arguably unlawful, process. Moreover, the HS2 project has been proposed in the absence of a soundly developed national strategic context against which to test its soundness in terms of fitness for purpose. The Society is drawn into this debate because, as a direct result of these process failures, an HSR route through the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) is proposed. This has been done without conclusive demonstration, as required by planning guidance2 and best practice, that no alternative that avoids the AONB is possible to meet the (currently undefined) ‘national interest’ need for an HSR network. 1.4 The Society is prepared to accept that there are prima facie arguments for reducing rail travel times between major cities and, importantly, improving connectivity to and between major centres in the English Midlands and the North. -

Coventry – Nuneaton Rail Line Upgrade MSBC Appraisal Summary

Coventry – Nuneaton Rail Line Upgrade MSBC Appraisal Summary September 2011 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Scheme Objectives 1 2 CURRENT SERVICE AND PASSENGER DEMAND 3 2.1 Existing Rail Service 3 2.2 Base Rail Demand 3 2.3 Recent Growth in Base Rail Demand 4 3 MODELLING APPROACH 6 3.1 Introduction 6 3.2 Scheme Elements 6 3.3 Modelling Approach 7 3.4 Summary of Approach 12 4 MODEL RESULTS 15 4.1 Base Demand on the Coventry – Nuneaton Line 15 5 ECONOMIC APPRAISAL 21 5.1 Introduction 21 5.2 Capital Costs 21 5.3 Operating Costs 21 5.4 Revenues and Subsidy 22 5.5 User and Non – User Benefits 22 5.6 Economic Appraisal 23 5.7 Cost Benefit Analysis Results 28 Table 1 Existing Timetable 3 Table 2 Preferred Scheme Timetable (Half-hourly) 8 Table 3 Coventry Arena Events Traffic Forecast 12 Table 4 Summary of Approach to Modelling Key Scheme Impacts 13 Table 5 Coventry – Nuneaton Passengers: Model vs November 2009 15 Table 6 2016 Do Minimum Weekday Passenger Forecast (2-hour periods) 16 Table 7 2016 Do Minimum Annual Passenger Forecast 17 Table 8 Historical West Midlands Rail Patronage Growth 17 Table 9 2016 Do Something Weekday Passenger Forecast (2-hour periods) 17 Table 10 2016 Do-Something Visum Model Annual Passenger Forecast 18 Table 11 2016 Long Distance and Arena Event Trips 19 Table 12 2016 Combined Annual Passenger Forecast 19 Table 13 2016 Additional Annual Passenger Forecast (DS – DM) 19 Table 14 Mode Share Analysis - Screenlines 20 Table 15 Capital Costs (1st Quarter 2011) 21 st Table 16 Annual Additional Operating Costs (1 Quarter 2011) 21 Table 17 Revenues and Subsidy, 2002 prices and Outturn Prices 22 Table 18 Breakdown of Quantified Benefits 24 Table 19 Monetised Time Benefits by Size of Time Saving (£k) 24 Coventry – Nuneaton Rail Line Upgrade, Appraisal Summary, September 2011 Table 20 Quantified Wider Economic Benefits (£k PV). -

RUGBY PARKWAY: a Feasibility Study Into a New Station to Serve the Rugby Radio Station Sustainable Urban Extension

RUGBY PARKWAY: A feasibility study into a new station to serve the Rugby Radio Station Sustainable Urban Extension 30 April 2015 Report Preparation Approval for issue version Prepared by Date Approved by Date 1.0 MH 30/04/2015 MH 30/04/2015 2.0 3.0 Final MH 12/06/2015 MH 12/06/2015 www.slcrail.com Page 1 of 35 Contents 1. Executive summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Station Site Options ............................................................................................................ 5 1.3 Capital Cost Estimate .......................................................................................................... 7 1.4 Timetabling Feasibility ........................................................................................................ 7 1.5 Demand Analysis ................................................................................................................. 8 2. Scope and purpose of report.......................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Objectives ............................................................................................................................ 8 2.2 Report structure ................................................................................................................. -

Letter Title

Campaigning for better services over a bigger rail network please reply to: ICWC Consultation 42 Quickrells Avenue Department for Transport Cliffe 4/18 Great Minster House Rochester 33 Horseferry Road Kent London SW1P 4DR ME3 7RB [email protected] [email protected] 1st August 2016 Dear Sir, Consultation: InterCity West Coast Rail Franchise Railfuture is a national independent voluntary organisation campaigning for a bigger, better railway in Britain, so we welcome the opportunity to provide an informed response to the questions of this consultation. The response has been coordinated by Trevor Bishop ([email protected]) the Ra0lifuture TOC liaison for this franchise. Railfuture recognises the importance of the provision of improved rail services offering more journey opportunities to a wider range of travellers by contributing to wider economic, employment and skills, social inclusion and environmental issues. Our response is attached. If you require any more detail, or clarification, please do not hesitate to get in touch. Yours sincerely Chris Fribbins Railfuture Head of Passenger Group www.railfuture.org.uk www.railfuturescotland.org.uk www.railfuturewales.org.uk www.railwatch.org.uk The Railway Development Society Limited is a (not for profit) Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in England and Wales No. 5011634. Registered Office:- 24 Chedworth Place, Tattingstone, Suffolk IP9 2ND InterCity West Coast rail franchise consultation Table of contents Respond in English - 2 Respond in Welsh - 17 Ymgynghoriad ar Ryddfraint Rheilffordd InterCity Arfordir y Gorllewin Tabl cynnwys Ymateb yn Saesneg - 2 Ymateb yn Gymraeg - 17 InterCity West Coast rail franchise consultation The Department for Transport is seeking the views of the public and stakeholders on the future of rail services, stations and other supporting services provided in the InterCity West Coast rail franchise. -

Railway Reminiscences

rafc ^' NQTJSS ''SUPEB/. CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY FROM Cornell University Library HE3018.2.N37 A3 Railway reminiscences. 3 1924 030 116 960 olin RAILWAY REMINISCENCES. All books are subject to recall after two weeks Olin/Kroch Library DATE DUE ' RAILWAY REMINISCENCES BY GEORGE P. NEELE, LATE SUTERINTENDENT OF THE LINE OF THE LONDON AND NORTH WESTERN RAILWAY. NOTES AND REMINISCENCES OF HALF A century's PROGRESS IN RAILWAY WORKING, AND OF A RAILWAY SUPERINTENDENT'S LIFE, PRINCIPALLY ON THE LONDON AND NORTH WESTERN RAILWAY, WITH SOME SUPPLEMENTARY MEMORANDA AS TO THE RAILWAY JOURNEYS TO AND FROM SCOTLAND MADE BY HER LATE MAJESTY QUEEN VICTORIA. XonDon: M'^CORQUODALE & CO., LIMITED, PRINTERS, CARDINGTON STREET. 1904. ^7 A77373S" PREFACE. Owing to suggestions made from time to time by old comrades in railway life, I have been induced to put together some record of the part I have taken in connection with the inner working of Railways; going back to very early experiences, and through gradual developments extending over a long series of years, to the time when it became advisable for me to retire from the daily pressure of the work. A railway service commencing in 1847, carries one back a long way towards association with those who were the actual pioneers of our railway system ; from whom we learnt our first lessons, by whose successes we have profited, by whose failures we have acquired knowledge ; and on whose foundation we have endeavoured to raise a superstructure of so sub- stantial a character, that those who follow in our steps will have no reason to be ashamed of their predecessors. -

Agenda Item 4 Strategic Rail Priorities 110920.Pdf

Strategic Transport Forum 11th September 2020 Agenda Item 4: Strategic Rail Priorities for the West Coast Main Line and Midland Main Line Recommendation: It is recommended that the Forum: a) Considers the region’s priorities for the West Coast Main Line and Midland Main Line b) Note, in that context, presentations provided from Avanti West Coast Partnership and East Midlands Railway setting out their current franchise priorities c) Reinforce, subject to amendments agreed by the Group, the Heartland’s long- term rail needs must be along both of these corridors to deliver on the ambitions set out in the Draft Transport Strategy 1. Strategic Context 1.1. The Draft Transport Strategy identifies the West Coast Main Line and Midland Main Line as two of the busiest and most important strategic rail corridors in the Heartland. Today, both play a vital role in providing commuting, inter-urban and inter-city services to some of the country’s highest performing labour markets and regionally significant hubs. Both operate as key rail freight arteries; with the West Coast Main Line carrying the region’s largest volumes of intermodal freight from deep-sea ports in the south east and the Midland Main Line moving significant flows of construction materials originating from Leicester and the Peak District. 1.2. Both networks require greater levels of infrastructure investment if they are to deliver on the ambitions of the Transport Strategy: delivering growth in a way that is both sustainable and achieves environmental net gain. The Strategy’s policy framework recognises that investment in these strategic rail corridors will act as a catalyst for sustainable change in our region and must be used to shape our partners’ future economic and housing growth proposals brought through the local plan process.