Q1 What Are the Main Arguments for Or Against HSR?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tourism Leaflet 2021

Visit Cannock Chase Your guide on getting more from your visit to Our Visitor Centres Birches Valley Visitor Centre Marquis Drive Visitor Centre Museum of Cannock Chase Cannock Chase National Trust Shugborough Estate The Cannock Chase District is nestled in the heart of the West Midlands, Chasewater Country Park in the county of Staffordshire. We are a historical, proud District spanning The Wolseley Centre - Staffordshire Wildlife Trust HQ across three town centres, Cannock, Hednesford and Rugeley. Some of our visitor centres sit just outside the district. For full details, take a look at page 13 Visit us to enjoy incredible shopping at McArthuGlen’s Designer Outlet West Midlands, only a 20 minute walk from Cannock town centre and only 10 minutes walk from Cannock Train Station. And why not explore, walk and mountain bike in the Cannock Chase Area Well Worth a Visit of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Less than 20 minutes drive from our three town centres. McArthurGlen Designer Outlet West Midlands Cannock Chase AONB Go Ape Hednesford Hills Raceway Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery Planet Ice Skating Rink Cannock Cinema Prince of Wales Theatre The Rugeley Rose Theatre Cannock Chase Leisure Centre and Golf Course Rugeley Leisure Centre Within the County Drayton Manor Theme Park SnowDome Alton Towers Resort Trentham Estate - Shopping, Monkey Forest and Gardens National Memorial Arboretum Photographs courtesy of Michelle Williams, 2 Margaret Beardsmore and Carole & David Perry 3 A well connected place... Heritage Trail Map By road By bus and coach A great walking and cycling route linking Rugeley, Hednesford & Cannock Cannock Chase The A5 and A34 AONB Bus links to all local and surrounding areas trunk roads, M6 and as well as wider areas including Central M6 toll provide Birmingham and Walsall. -

Infrastructure Delivery Plan Contents 1 Introduction 3

APPENDIX O Infrastructure Delivery Plan 1 March 2018 Infrastructure Delivery Plan Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Policy Context 5 3 Funding & Delivery 8 4 Strategic Infrastructure 11 5 Local Infrastructure Needs 58 Appendices A Lichfield District Integrated Transport Strategy 93 B River Mease SAC Water Catchment Area 94 C Cannock Chase SAC Zone of Influence 96 March 2018 Infrastructure Delivery Plan 3 1 Introduction 1.1 Infrastructure Planning is an essential element in ensuring that the Local Plan Strategy and Local Plan Allocation Document is robust and deliverable. 1.2 The term infrastructure is broadly used for planning purposes to define all of the requirements that are needed to make places function efficiently and effectively and in a way that creates sustainable communities. Infrastructure is commonly split into three main categories, defined as: Introduction Physical: the broad collection of systems and facilities that house and transport people and goods, and provide services e.g. transportation networks, housing, energy supplies, 1 water, drainage and waste provision, ICT networks, public realm and historic legacy. Green: the physical environment within and between our cities, towns and villages. A network of multi-functional open spaces, including formal parks, gardens, woodland, green corridors, waterways, street trees and open countryside. Social & Community: the range of activities, organisations and facilities supporting the formation, development and maintenance of social relationships in a community. It can include the provision -

East West Rail Western Section Phase 2

EAST WEST RAIL WESTERN SECTION PHASE 2 CONSULTATION INFORMATION DOCUMENT JUNE 2017 Document Reference 133735-PBR-REP-EEN-000026 Author Network Rail Date June 2017 Date of revision and June 2017 revision number 2.0 The Network Rail (East West Rail Western Section Phase 2) Order Consultation Information Document TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 2 2.1 Purpose of this consultation ...................................................................... 2 2.2 Structure of this consultation ..................................................................... 2 3. EAST WEST RAIL .............................................................................................. 4 3.1 Background ............................................................................................... 4 3.2 EWR Western Section ............................................................................... 5 4. EAST WEST RAIL WESTERN SECTION PHASE 2 .......................................... 8 4.1 Benefits ..................................................................................................... 8 4.2 Location ..................................................................................................... 8 4.3 Consenting considerations ...................................................................... 11 4.4 Interface with the High Speed -

Reunification East Midlands G R Y E a a W T C Il Entral Ra

DONATE BY TEXT! REUNIFICATION EAST MIDLANDS G R Y E A A W T C IL ENTRAL RA THE UK’S BIGGEST HERITAGE RAILWAY PROJECT Reconnecting two halves of the Great Central Railway and joining them to Network Rail Supported by David Clarke Railway Trust Friends of the Great Central Main Line East Midlands Railway Trust www.gcrailway.co.uk/unify POTENTIAL EXTENSION TO TRAM INTERCHANGE NOTTINGHAM TRANSPORT HERITAGE CENTRE RUSHCLIFFE HALT REUNIFICATION EAST MIDLANDS G R Y E A A W T C IL ENTRAL RA SITE OF EAST LEAKE STATION By replacing five hundred metres of BARNSTONE missing track between two sections N TUNNEL of the Great Central Railway, we can NOT TO SCALE create an eighteen-mile heritage line STANFORD VIADUCT complete with a main line connection. This is no impossible dream - work is CONNECTION TO THE MISSING MIDLAND MAIN LINE underway, but we need your help to SECTION get the next sections built. LOUGHBOROUGH LOCOMOTIVE SHED TO EAST LEAKE AND RUDDINGTON LOUGHBOROUGH CENTRAL STATION A60 ROAD BRIDGE REQUIRES OVERHAULING EMBANKMENT REQUIRES REPAIRING QUORN & WOODHOUSE STATION MIDLAND MAIN LINE BRIDGE ✓ NOW BUILT! FACTORY CAR PARK SWITHLAND CROSSING REQUIRES CONTRUCTION VIADUCT RAILWAY TERRACE BRANCH LINE TO ROAD BRIDGE TO BE CONSTRUCTED USING MOUNTSORREL RECLAIMED BRIDGE DECK HERITAGE CENTRE ROTHLEY EMBANKMENT STATION NEEDS TO BE BUILT POTENTIAL DOUBLE TRACK GRAND UNION TO LEICESTER ✓ CANAL BRIDGE NOW RESTORED LEICESTER NORTH STATION TO LEICESTER REUNIFICATION Moving Forward An exciting adventure is underway. Following Two sections of the work have been the global pandemic, we’re picking up the completed already, which you can read all pace to build an exciting future for the Great about here. -

WMRU June 2014 Cover

West Midlands Rail User Issue 8 JUNE 2014 £2 www.campaignforrail.org.uk ON OTHER PAGES: 10. Rail continues to grow ON OTHER PASGES: 2. Comment 11. Metro developments 3.BirminghamCurzon 12.Whypaymore? 4. Cross City South grows 13. Bushbury Junction 6. CfR’s Annual Meeting 14. Snippets 7. TripleTriumphforStourbridgeGroup 15. Thenextstationis…..Stone 8. TheFutureisWestMidlandsRail 16. TrackliftedtoCauldonLowe The voice of Campaign for Rail in the West Midlands COMMENT Imagine buying a vacuum cleaner and taking it back next day because it didn’t work. ‘Were you trying to use late afternoon? It’s not valid at that time. We didn’t tell you when we sold you it.’ Instead of vacuum cleaner, read ‘off peak rail ticket’. Twice recently I have bought rail tickets from booking clerks who have only asked if I am travelling after 09.30. In both cases, I later discovered they were not valid for my afternoon return journey. The problem is with Cross Country. It has decided some afternoon trains are ‘peak’ but it doesn’t identify them in its timetables and Cross Country unhelpfully only tells us, ‘off peak times vary by route’. As the i newspaper said about rail tickets re- cently, ‘Peak time is now more difficult to define in a sentence than the Higgs boson.’ Equally useless from Cross Country is, ‘Break of journey is generally permitted unless prohibited for the journey you are making.’ Each ticket says, ‘Route: Any permitted’ and ‘Validity: See restrictions.’ But where? A CfR member tried to buy a ticket to Kidderminster which involved going south via Bromsgrove to Droitwich Spa and then doubling back. -

Signal and Track Improvements for Trent Valley Line Passengers

Signal and track improvements for Trent Valley Line passengers July 19, 2021 Rail passengers travelling between Stafford and Rugby are being urged to ‘look before they book’ ahead of a month of weekend railway upgrades. The major improvements to the Trent Valley Line will see new railway track laid and signalling – the traffic lights of the railway – improved. Once complete, it will mean smoother, more reliable journeys for passengers who use this busy stretch of the West Coast main line. Passengers are being urged to check www.nationalrail.co.uk to plan their journeys while the essential work is carried out on 24-25 July, 31 July-1 August, 7-8 August and 14-15 August. To keep London Northwestern Railway and West Midlands Railway passengers on the move, buses will replace trains between: Rugby – Stafford Hednesford – Rugeley Trent Valley Bermuda Park/Coventry Arena – Nuneaton A revised timetable will be in place to minimise disruption for passengers. Avanti West Coast passengers will also see fewer trains and slightly longer journey times with services diverted via Birmingham New Street. James Dean, Network Rail’s West Coast South route director, said: “We’re really pleased to be investing in the Trent Valley Line so that passengers get the journeys they deserve as they continue to return to the railway. The investment is a key part of our work to support the post-pandemic recovery, helping the country build back better. “Services will only be affected during the weekends with some journeys replaced by buses to ensure passengers can still get to where they need to be. -

High Speed Two Limited

High Speed Two Limited High Speed 2 Infrastructure Maintenance Depot (IMD) High Speed Two Limited H igh Speed 2 Infrastructure Maintenance Depot (IMD) March 2011 This r eport t akes i nto a ccount t he particular instructions and requirements of our client. It i s not i ntended f or a nd s hould n ot be relied u pon b y any third p arty a nd no responsibility i s u ndertaken to any t hird Ove Arup & Partners Ltd party The Arup Campus, Blythe Gate, Blythe Valley Park, Solihull, West Midlands. B90 8AE Tel +44 (0)121 213 3000 Fax +44 (0)121 213 3001 www.arup.com Job number High Speed Two (HS2) High Speed 2 Infrastructure Maintenance Depot Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The December 2009 Report 1 1.2 Layout of this Report 1 2 Scope of Work, Methodology and Deliverables 2 2.1 Scope of Work 2 2.2 Meeting 1 2 2.3 Intermediate instructions 3 2.4 Meeting 2 3 3 Current Rail Operations and Future Developments 4 3.1 Context 4 3.2 Oxford - Bletchley 4 3.3 Aylesbury – Claydon Line 4 3.4 High Speed 2 5 3.5 Evergreen 3 5 3.6 East West Project 5 4 Functional Requirements 6 5 Site Location Options 7 5.1 Introduction 7 5.2 Quadrant 1 9 5.3 Quadrant 2 11 5.4 Quadrant 3 15 5.5 Quadrant 4 17 5.6 Sites on HS2 (north) 18 6 Cost Estimates 20 6.1 Matrix table for all Site options 20 7 Conclusion 21 8 Selected Option Development 23 8.1 General layout 23 8.2 Specific site details 27 8.3 Site operation 28 8.4 West end connections 29 9 Calvert Waste Plant 30 9.1 Rail Access 30 9.2 Heat and power generation 32 10 Use of site as a potential construction depot 33 -

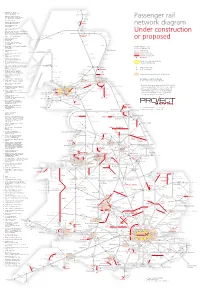

Rail Map REOP7 15.9

1 2 A2B Drumgelloch - Bathgate Thurso reopening in progress due Dec 2010 by the Scottish Parliament Georgemas Wick 3 GARL Glasgow Airport new rail link by the Scottish Parliament November 2002 due to open 2012 but cancelled 2009 Passenger rail Helmsdale 4 Unrecorded, refer to 63 Golspie 5 Edinburgh suburban line reopening Lairg 59 November 2002, cancelled 2009 Dornoch 6 Penicuik reopening proposal network diagram November 2002 Tain Garve 7 Borders reopening under planning Invergordon by the Scottish Parliament Dingwall 8 Blythe & Tyne and Leamside lines reopening proposal September 2002 and Feb 2008 Nairn Elgin Under construction Also Ashington & Blythe and Washington proposals by Keith ATOC Connecting Communities June 2009 Achnasheen Inverness Strathcarron Inverness Forres 9 Penrith - Keswick reopening proposal 64 Airport Huntly Plockton 10 Stanhope - Bishops Auckland Stromeferry reopening proposal or proposed November 2002 Kyle of Lochalsh Aviemore Inverurie 11 Pickering - Rillington reopening to enable through service over Yorkshire Moors railway Kingussie Dyce 12 Wensleydale Railway: Northallerton - Leaming Bar - SCOTRAIL Leyburn - Redmire Principal routes November 2002 Regional routes 13 Rippon reopening proposal Spean Aberdeen Local routes July 2004 Glenfinnan Bridge Mallaig Limited service 14 Grassington branch reopening proposal September 2002 Blair Atholl Fort William Stonehaven Under construction 15 Skipton - Colne reopening proposal Planned or proposed* September 2002 Pitlochry New station 16 York - Beverley reopening proposal -

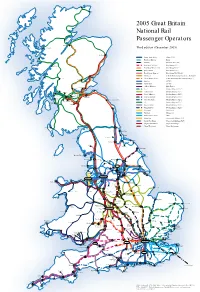

2005 Great Britain National Rail Passenger Operators Dingwall

Thurso Wick 2005 Great Britain National Rail Passenger Operators Dingwall Inverness Kyle of Lochalsh Third edition (December 2005) Aberdeen Arriva Trains Wales (Arriva P.L.C.) Mallaig Heathrow Express (BAA) Eurostar (Eurostar (U.K.) Ltd.) First Great Western (First Group P.L.C.) Fort William First Great Western Link (First Group P.L.C.) First ScotRail (First Group P.L.C.) TransPennine Express (First Group P.L.C./Keolis) Hull Trains (G.B. Railways Group/Renaissance Railways) Dundee Oban Crianlarich Great North Eastern (G.N.E.R. Holdings/Sea Containers P.L.C.) Perth Southern (GOVIA) Thameslink (GOVIA) Chiltern Railways (M40 Trains) Cardenden Stirling Kirkcaldy ‘One’ (National Express P.L.C.) North Berwick Balloch Central Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Gourock Milngavie Cumbernauld Gatwick Express (National Express P.L.C.) Bathgate Wemyss Bay Glasgow Drumgelloch Edinburgh Midland Mainline (National Express P.L.C.) Largs Berwick upon Tweed Silverlink Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Neilston East Kilbride Carstairs Ardrossan c2c (National Express P.L.C.) Harbour Lanark Wessex Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Chathill Wagn Railway (National Express P.L.C.) Merseyrail (Ned-Serco) Northern (Ned-Serco) South Eastern Trains (SRA) Island Line (Stagecoach Holdings P.L.C.) South West Trains (Stagecoach Holdings P.L.C.) Virgin CrossCountry (Virgin Rail Group) Virgin West Coast (Virgin Rail Group) Newcastle Stranraer Carlisle Sunderland Hartlepool Bishop Auckland Workington Saltburn Darlington Middlesbrough Whitby Windermere Battersby Scarborough -

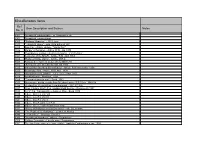

Miscellaneous Items Ref Item Description and Source Notes No

Miscellaneous Items Ref Item Description and Source Notes No. X X003 Scrapbook, photographs - ex. Magazines etc. X004 Scrapbook, newscuttings X007 "Railway Magazine" - 1912 June X012 "Travels at Home" - pub. With authy of G.C X015 Sam Fay - Article, picture, "Vanity Fair" X016 Murder in Pennines - Article, R.W. Jan 1970 X017 Past Glories, station refreshment rooms - V.R.Webster X021 A veteran of the MSLR - Article, R.M. April 1959 X022 Wadsley bridge station - Article, M.R.C X023 Railway development at Aylesbury BM No 55 X024 Diversions over Woodhead RM Jan 1970 X025 Manchester-Sheffield Electrification - Article, R.M. November 1954 X026 Bowbridge Pilot - Article, R.M. Nov. 1954 X027 Abandonment of SAMR? - letter, Dec. 22nd. 1837 X028 Accident book - Mexboro', 1925 X029 "Transport goes to war" - Book, 1942 X033 Occurrence books, mainly from Mexboro' area - B.R 16 no. 1948-58 X036 Prospectus, Preservation Loughborough - G.C.R 1976 X037 Prop. Closure Sheff.-Pen.-Huddersfield Service - Documents 1981 X038 S.Y.P.T.E. Transport Development Plan - Book 1978 X039 Index - G.C.R.J Vol. VIII X040 Index - G.C.R.J Vol. IX X041 Index - G.C.R.J Vol. X X042 Index - G.C.R articles in R.M X043 Index - G.C.R. LDECR articles in R.M X044 History of Railways around Doncaster - Ms, D.L.Franks X045 "The Plight of the Railways" - Leaflet, G.Huxley X046 "I remember" - Glossop - Booklet X049 "Woodhead Wanderer" railtour - Programme X050 Railtour Doncaster - Lincoln area - Programme X051 The Iron horse comes to town - Article, Appleby-Frodingham news, 1959 X054 The Yarborough Hotel - Notes, from Bradshaw 1853 X055 When service had meaning, The Story of and Early Railwayman's life - D.L Franks X056 Seven ages of Rlys - Ms, D.L. -

9. Impact of HS2 Phase 2 on MML Upgrade Programme

Midland Mainline Upgrade Programme Economic Case Report OFFICIAL SENSITIVE: COMMERCIAL 6. Operating Costs 6.1. Introduction This chapter presents the operating cost (“opex”) estimates for each rolling stock option on the upgraded Midland Mainline. Operating costs were estimated for each option using the Comparator Suite developed for the East Midlands franchise competition. The model estimates costs for operating long-distance services on the MML in the baseline scenario and in each of the options to be appraised. The difference between the option costs and the baseline cost is the figure carried forward to the appraisal. The operating cost model considered the variable elements of operating costs only, as follows: • Network Rail infrastructure costs; • Diesel and electricity costs; • Capital lease costs; • Non-capital lease costs; • Maintenance costs; and • Staff costs. Within the operating cost model, the following inputs are used to drive changes in the operating costs: • Estimated rolling stock fleet size (number of trains and number of vehicles); • Requirement for additional staff to operate the 6 th path; • Forecast train and vehicle mileages; • Light and heavy maintenance materials (for HSTs). The following sections provide further details on the input costs, growth rates and other assumptions for each of the above cost areas. 6.2. Train and Vehicle Mileages Train and vehicle mileages are required for the calculation of infrastructure costs (variable track access charge, capacity charge, electrification asset usage charge, energy costs (diesel and electric power) and maintenance costs). Annual train and vehicle mileages were calculated based on the timetable developed for business case testing and are shown for the respective rolling stock options in the table below. -

East Midlands Rail Franchise Stakeholder Briefing Document and Consultation Response

East Midlands Rail Franchise Stakeholder Briefing Document and Consultation Response Driving Growth in the East Midlands June 2018 Stakeholder Briefing Document | East Midlands Rail Franchise Stakeholder Briefing Document | East Midlands Rail Franchise The Department for Transport has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the Department’s website in English and Welsh. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard, please contact the Department: Department for Transport Great Minster House 33 Horseferry Road London SW1P 4DR Telephone 0300 330 3000 Website: www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-transport General enquiries: https://forms.dft.gov.uk © Crown copyright 2018 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos or third-party material) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/ or write to The Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU. Further contact details are available on http://apps.nationalarchives.gov.uk/Contact/ Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Stakeholder Briefing Document | East Midlands Rail Franchise Stakeholder Briefing Document | East Midlands Rail Franchise Contents 1. Foreword Foreword by the Secretary of State 3 2. Introduction What is this document for? 7 3.