The Provision of Water Infrastructure in Aboriginal Communities in South Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit Trachoma Surveillance Report 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NATIONAL TRACHOMA SURVEILLANCE AND REPORTING UNIT TRACHOMA SURVEILLANCE REPORT 2008 AUGUST 2009 Prepared by Ms Betty Tellis Ms Kathy Fotis Mr Ross Dunn Professor Jill Keeffe Professor Hugh Taylor Centre for Eye Research Australia, University of Melbourne National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit Trachoma Surveillance Report 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit’s third Surveillance Report 2008 was compiled using data collected and/or reported by the following organisations and departments. STATE AND TERRITORY CONTRIBUTIONS NORTHERN TERRITORY • Australian Government Emergency Intervention (AGEI) • Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS) • Centre for Disease Control, Northern Territory Department of Health and Families, Northern Territory • Healthy School Age Kids (HSAK) program: Top End • HSAK: Central Australia SOUTH AUSTRALIA • Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia, Eye Health and Chronic Disease Specialist Support Program (EH&CDSSP) • Country Health South Australia • Ceduna/Koonibba Health Service • Nganampa Health Council • Oak Valley (Maralinga Tjarutja) Health Service • Pika Wiya Health Service • Tullawon Health Service • Umoona Tjutagku Health Service WESTERN AUSTRALIA • Communicable Diseases Control Directorate, Department of Health, Western Australia • Population Health Units and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services staff in the Goldfields, Kimberley, Midwest and Pilbara regions OTHER CONTRIBUTIONS ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE • Institute of Medical Veterinary -

Indigenous Design Issuesceduna Aboriginal Children and Family

INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ 1 INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ 2 INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWELDGEMENTS............................................................................................................ 5 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 5 PART 1: PRECEDENTS AND “BEST PRACTICE„ DESIGN ....................................................10 The Design of Early Learning, Child-care and Children and Family Centres for Aboriginal People ..................................................................................................................................10 Conceptions of Quality ........................................................................................................ 10 Precedents: Pre-Schools, Kindergartens, Child and Family Centres ..................................12 Kulai Aboriginal Preschool ............................................................................................. -

(G-FLOWS) Task 6: Groundwater Recharge

Facilitating Long Term Out‐Back Water Solutions (G‐FLOWS) Task 6: Groundwater recharge characteristics across key priority areas Leaney, FW, Taylor, AR, Jolly, ID and Davies PJ Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 13/6 www.goyderinstitute.org Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series ISSN: 1839‐2725 The Goyder Institute for Water Research is a partnership between the South Australian Government through the Department for Environment, Water and Natural Resources, CSIRO, Flinders University, the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia. The Institute will enhance the South Australian Government’s capacity to develop and deliver science‐based policy solutions in water management. It brings together the best scientists and researchers across Australia to provide expert and independent scientific advice to inform good government water policy and identify future threats and opportunities to water security. Enquires should be addressed to: Goyder Institute for Water Research Level 1, Torrens Building 220 Victoria Square, Adelaide, SA, 5000 tel: 08‐8303 8952 e‐mail: [email protected] Citation Leaney, FW, Taylor, AR, Jolly, ID, and Davies PJ, 2013, Facilitating Long Term Out‐Back Water Solutions (G‐FLOWS) Task 6: Groundwater recharge characteristics across key priority areas, Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 13/6, Adelaide, South Australia Copyright © 2013 CSIRO To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. Disclaimer The Participants advise that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research and does not warrant or represent the completeness of any information or material in this publication. -

A Collaborative History of Social Innovation in South Australia

Hawke Research Institute for Sustainable Societies University of South Australia St Bernards Road Magill South Australia 5072 Australia www.unisa.edu.au/hawkeinstitute © Rob Manwaring and University of South Australia 2008 A COLLABORATIVE HISTORY OF SOCIAL INNOVATION IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA Rob Manwaring∗ Abstract In this paper I outline a collaborative history of social innovation in South Australia, a state that has a striking record of social innovation. What makes this history so intriguing is that on the face of it, South Australia would seem an unlikely location for such experimentation. This paper outlines the main periods of innovation. Appended to it is the first attempt to collate all these social innovations in one document. This paper is unique in that its account of the history of social innovation has been derived after public consultation in South Australia, and is a key output from Geoff Mulgan’s role as an Adelaide Thinker in Residence.1 The paper analyses why, at times, South Australia appears to have punched above its weight as a leader in social innovation. Drawing on Giddens’ ‘structuration’ model, the paper uses South Australian history as a case study to determine how far structure and/or agency can explain the main periods of social innovation. Introduction South Australia has a great and rich (albeit uneven) history of social innovation, and has at times punched above its weight. What makes this history so intriguing is that on the face of it, South Australia is quite an unlikely place for such innovation. South Australia is a relatively new entity; it has a relatively small but highly urbanised population, and is geographically isolated from other Australian urban centres and other developed nations. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Presentation Tile

Authentic and engaging artist-led Education Programs with Thomas Readett Ngarrindjeri, Arrernte peoples 1 Acknowledgement 2 Warm up: Round Robin 3 4 See image caption from slide 2. installation view: TARNANTHI featuring Mumu by Pepai Jangala Carroll, 2015, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; photo: Saul Steed. 5 What is TARNANTHI? TARNANTHI is a platform for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists from across the country to share important stories through contemporary art. TARNANTHI is a national event held annually by the Art Gallery of South Australia. Although TARNANTHI at AGSA is annual, biannually TARNANTHI turns into a city-wide festival and hosts hundreds of artists across multiple venues across Adelaide. On the year that the festival isn’t on, TARNANTHI focuses on only one feature artist or artist collective at AGSA. Jimmy Donegan, born 1940, Roma Young, born 1952, Ngaanyatjarra people, Western Australia/Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia; Kunmanara (Ray) Ken, 1940–2018, Brenton Ken, born 1944, Witjiti George, born 1938, Sammy Dodd, born 1946, Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara people, South Australia; Freddy Ken, born 1951, Naomi Kantjuriny, born 1944, Nyurpaya Kaika Burton, born 1940, Willy Kaika Burton, born 1941, Rupert Jack, born 1951, Adrian Intjalki, born 1943, Kunmanara (Gordon) Ingkatji, c.1930–2016, Arnie Frank, born 1960, Stanley Douglas, born 1944, Maureen Douglas, born 1966, Willy Muntjantji Martin, born 1950, Taylor Wanyima Cooper, born 1940, Noel Burton, born 1994, Kunmanara (Hector) Burton, 1937–2017, -

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~Ent No. \

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~ent No. \, By: Mr~ C'-tn~:S AOlSC, Date: b IV\a,c<J..-. J,od.D , e,. t\-40.M I ---------- - ~ -- Australian Government National IndigeJrums Australlfans Agency OFFICIAL Chief Executive Officer Ray Griggs AO, CSC Reference: EC20~000257 Senator Tim Ayres Labor Senator for New South Wales Deputy Chair, Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee 6 March 2020 Re: Additional Estimates 2019-2020 Dear Senatafyres ~l Thank you for your letter dated 25 February 2020 requesting information about Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) and Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA) grants and unsuccessful applications for the periods 1 January- 30 June 2019 and 1 July 2019 (Agency establishment) - 25 February 2020. The National Indigenous Australians Agency has prepared the attached information; due to reporting cycles, we have provided the requested information for the period 1 January 2019 - 31 January 2020. However we can provide the information for the additional period if required. As requested, assessment scores are provided for the merit-based grant rounds: NAIDOC and ABA. Assessment scores for NAIDOC and ABA are not comparable, as NAIDOC is scored out of 20 and ABA is scored out of 15. Please note as there were no NAIDOC or ABA grants/ unsuccessful applications between 1 July 2019 and 31 January 2020, Attachments Band D do not include assessment scores. Please also note the physical location of unsuccessful applicants has been included, while the service delivery locations is provided for funded grants. In relation to ABA grants, we have included the then Department's recommendations to the Minister, as requested. -

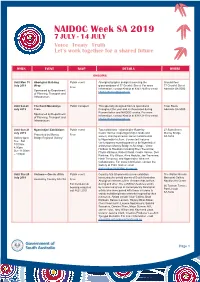

NAIDOC Week SA 2019 7 JULY - 14 JULY Voice

NAIDOC Week SA 2019 7 JULY - 14 JULY Voice . Treaty . Truth Let’s work together for a shared future WHEN EVENT RSVP DETAILS WHERE ONGOING Until Mon 15 Aboriginal Building Public event Aboriginal graphic design is covering the Ground floor July 2019 Wrap glass windows of 77 Grenfell Street. For more 77 Grenfell Street Free information, contact Khatija at 8343 2449 or email Adelaide SA 5000 Sponsored by Department [email protected] of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Until Sat 20 The Kardi Munaintya Public transport This specially designed tram is operational Tram Route July 2019 Tram throughout the year and is showcased during Adelaide SA 5000 Reconciliation and NAIDOC weeks. For more Sponsored by Department information, contact Khatija at 8343 2449 or email of Planning, Transport and [email protected] Infrastructure Until Sun 21 Ngarrindjeri Exhibitions Public event Two exhibitions - Ngarrindjeri Ruwe by 27 Sixth Street July 2019 Cedric Varcoe maps Ngarrindjeri lands and Murray Bridge Presented by Murray Free waters, sharing ancestor stories fundamental SA 5253 Gallery open Bridge Regional Gallery to Ngarrindjeri culture. Connected features Tue - Sat contemporary weaving practices by Ngarrindjeri 10:00am – artists from Murray Bridge to Meningie, Victor 4:00pm Harbour to Raukkan including Ellen Trevorrow, Sun 11:00am Phyllis Williams, Robert Wuldi, Cedric Varcoe, Deb – 4:00pm Rankine, Elly Wilson, Alice Abdulla, Joe Trevorrow, Hank Trevorrow, and Ngarrindjeri Weavers Collaborators. For more information, contact the Gallery at 8539 1420 or email [email protected] Until Thu 25 Vietnam – One In, All In Public event Country Arts SA presents a new exhibition The Walter Nichols July 2019 honouring the untold stories of South Australian Memorial Gallery Hosted by Country Arts SA Free Aboriginal veterans of the Vietnam War, before, Nautilus Art Centre For Port Lincoln during and after. -

Tough(Er) Love Art from Eyre Peninsula

tough(er) love art from Eyre Peninsula COUNTRY ARTS SA LEARNING CONNECTIONS RESOURCE KIT AbOUT THIS RESOURCE KIT This Resource kit is published to accompany the exhibition tough(er) love: art from Eyre Peninsula at the Flinders University City Gallery, February 23 – April 28 2013 and touring regionally with Country Arts SA 2013 – 2015. This Resource kit is designed to support learning outcomes and teaching programs associated with viewing the tough(er) love exhibition by: • Providing information about the artists • Providing information about key works • Exploring Indigenous perspectives within contemporary art • Challenging students to engage with the works and the exhibition’s themes • Identifying ways in which the exhibition can be used as a curriculum resource • Providing strategies for exhibition viewing, as well as pre and post-visit research • It may be used in conjunction with a visit to the exhibition or as a pre-visit or post-visit resource. ACKNOWLEdgEMENTS Resource kit written by John Neylon, art writer, curator and arts education consultant. The writer acknowledges the particular contribution of all the artists and the following people to the development of this resource: COUNTRY ARTS SA Craig Harrison, Manager Artform Development Jayne Holland, Development Officer Western Eyre Penny Camens, Coordinator Arts Programs Anna Goodhind, Coordinator Visual Arts Pip Gare, Web and Communications Officer Tammy Hall, Coordinator Audience Development Beth Wuttke, Graphic Designer FLINDERS UNIVERSITY Fiona Salmon, Director Flinders University Art Museum & City Gallery Celia Dottore, Exhibitions Manager TOUGH(ER) LOVE RESOURCE KIT 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS BACKGROUND . 4 About this exhibition ............................................................................. 4 BACKGROUND The Artists ......................................................................................... 4 BEHIND THE SCENES The Curator ....................................................................................... -

Spirit Festival Takes Centre Stage

Aboriginal Way Issue 48, Mar 2012 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Spirit Festival takes centre stage Tandanya, the National Aboriginal Cultural Institute has hosted another successful Spirit Festival. Thousands of people attended, immersing themselves in Aboriginal and Islander culture. Left is Panjiti Lewis from Ernabella. For more photos from the Spirit Festival turn to pages 8 and 9. Photo supplied by Tandanya andRaymond Zada.Photosupplied Tandanya by Judges and magistrates have The Ripple Effect Supreme Court Judges and with assistance from Courts Administration Magistrates from Adelaide have Authority Aboriginal Programmes Manager taken steps to break down the Ms Sarah Alpers and Senior Aboriginal cultural barriers between Aboriginal Justice Officer Mr Paul Tanner. people and the legal system by The visit promoted cross-cultural spending time on the Anangu awareness between the judiciary and Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands. Aboriginal communities, and to improve Not only did 17 judges and magistrates understanding between the cultures spend five days and nights on the lands about law and justice matters. visiting communities but a DVD has been Justice Sulan said the trip was also in made of the trip so that others can learn keeping with Recommendation 96 of the from the experience. 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal The DVD is called The Ripple Effect and it Deaths in Custody. explains how decisions made by judges “…that recommendation calls on Australian and magistrates affect entire communities judiciary to make itself aware of Aboriginal hundreds of kilometres away. culture and practices through cultural The DVD was launched at a ceremony in the awareness programs and informal Above: Caption. -

A Response to the National Water Initiative from Nepabunna, Yarilena, Scotdesco and Davenport Aboriginal Settlements

36 A response to the National Water initiative from Nepabunna, Yarilena, Scotdesco and Davenport Aboriginal settlements Scotdesco and Davenport Yarilena, initiative from Nepabunna, response to the National Water A A response to the National Water Meryl Pearce Report initiative from Nepabunna, Yarilena, Eileen Willis Carmel McCarthy 36 Scotdesco and Davenport Fiona Ryan Aboriginal settlements Ben Wadham 2008 Meryl Pearce A response to the National Water Initiative from Nepabunna, Yarilena, Scotdesco and Davenport Aboriginal settlements Meryl Pearce Eileen Willis Carmel McCarthy Fiona Ryan Ben Wadham 2008 Contributing author information Dr Meryl Pearce is a Senior lecturer in the School of Geography, Population and Environmental Management at Flinders University. Her research focuses on water resource sustainability. Associate Professor Eileen Willis is a sociologist with research interests in Aboriginal health with a social determinants focus. Carmel McCarthy has broad ranging expertise in social, medical, and educational research. Fiona Ryan has participated in research projects related to Aboriginal issues and Aboriginal languages. She has a Masters in Applied Linguistics from Adelaide University and has worked extensively in the area of adult education. Dr Ben Wadham is a senior lecturer in the School of Education, Flinders University. His research has focused on Aboriginal reconciliation and Australian race relations from a governance and policy perspective. Desert Knowledge CRC Report Number 36 Information contained in this publication may be copied or reproduced for study, research, information or educational purposes, subject to inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source. ISBN: 1 74158 085 4 (Print copy) ISBN: 1 74158 086 2 (Online copy) ISSN: 1832 6684 Citation Pearce M, Willis E, McCarthy C, Ryan F and Wadham B. -

Australian Radiation Laboratory R

AR.L-t*--*«. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. HOUSING & COMMUNITY SERVICES Public Health Impact of Fallout from British Nuclear Weapons Tests in Australia, 1952-1957 by Keith N. Wise and John R. Moroney Australian Radiation Laboratory r. t J: i AUSTRALIAN RADIATION LABORATORY i - PUBLIC HEALTH IMPACT OF FALLOUT FROM BRITISH NUCLEAR WEAPONS TESTS IN AUSTRALIA, 1952-1957 by Keith N Wise and John R Moroney ARL/TR105 • LOWER PLENTY ROAD •1400 YALLAMBIE VIC 3085 MAY 1992 TELEPHONE: 433 2211 FAX (03) 432 1835 % FOREWORD This work was presented to the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia in 1985, but it was not otherwise reported. The impetus for now making it available to a wider audience came from the recent experience of one of us (KNW)* in surveying current research into modelling the transport of radionuclides in the environment; from this it became evident that the methods we used in 1985 remain the best available for such a problem. The present report is identical to the submission we made to the Royal Commission in 1985. Developments in the meantime do not call for change to the derivation of the radiation doses to the population from the nuclear tests, which is the substance of the report. However the recent upward revision of the risk coefficient for cancer mortality to 0.05 Sv"1 does require a change to the assessment we made of the doses in terms of detriment tc health. In 1985 we used a risk coefficient of 0.01, so that the estimates of cancer mortality given at pages iv & 60, and in Table 7.1, need to be multiplied by five.